|

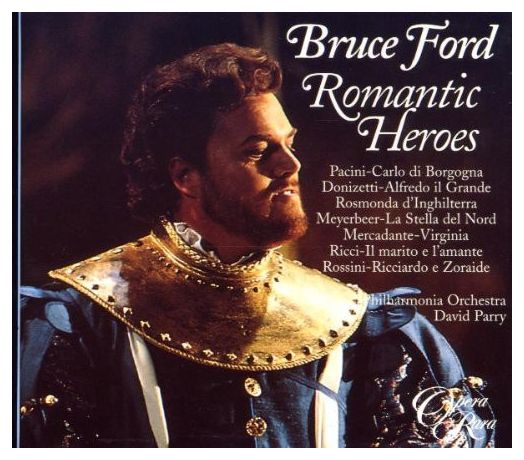

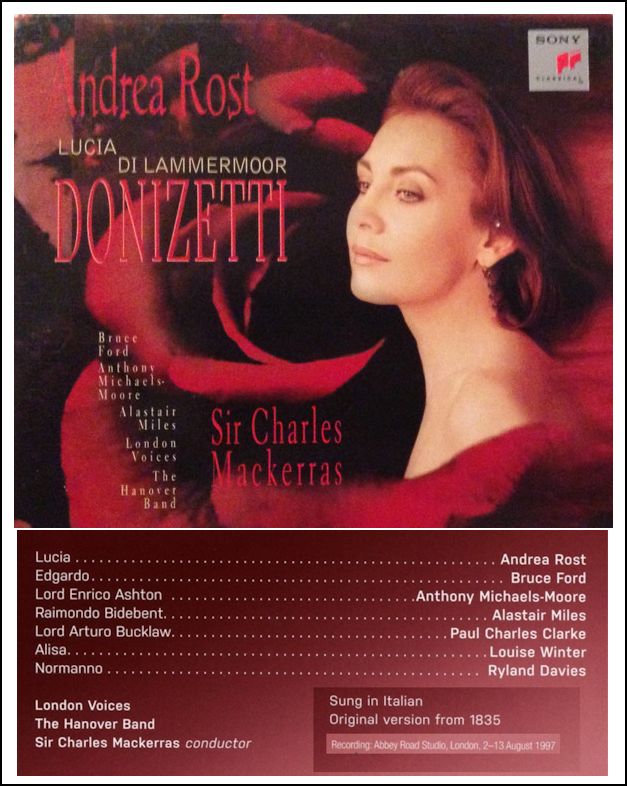

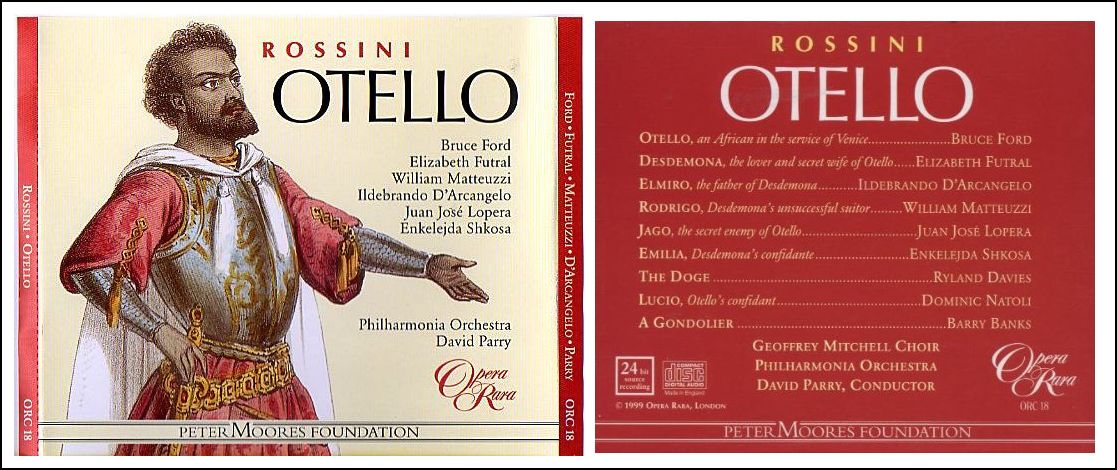

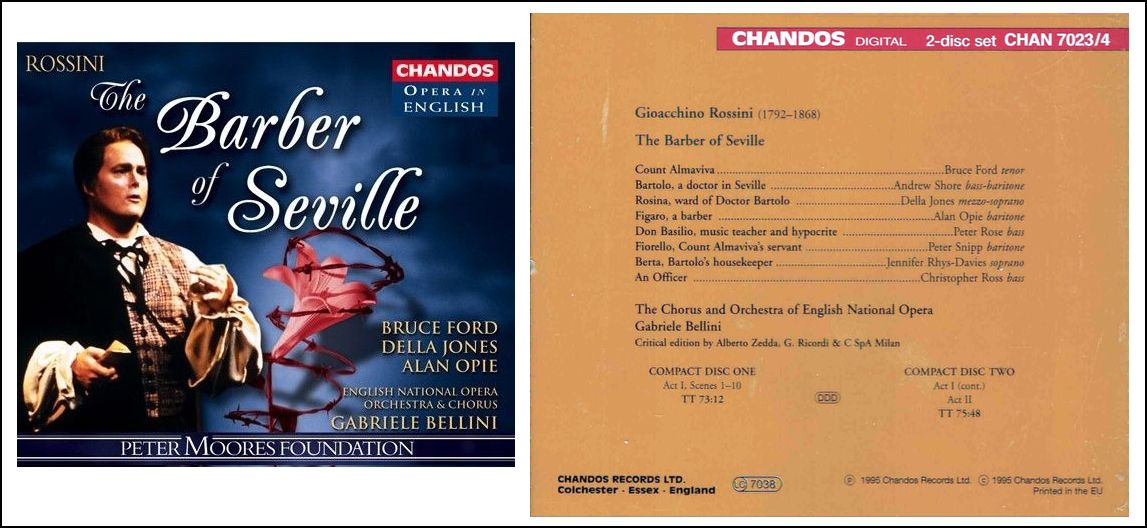

American tenor Bruce Ford was born in Texas in 1956 and trained

at the Houston Grand Opera Studio. He relocated to Europe to begin his

professional career in the early 1980s. Mozart figured prominently in his

early years, but it was his portrayals of the high-lying tenor roles in

Rossini’s opera serie (Uberto in La donna de Lago, Oreste

in Ermione, Argirio in Tancredi and the title-role in

Otello) that won him international acclaim.

|

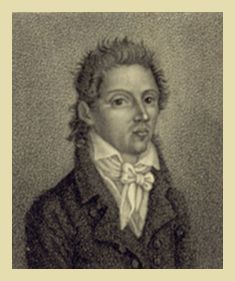

Giovanni David (15 September 1790 in Naples – 1864 in Saint

Petersburg) was an Italian tenor particularly known for his roles in

Rossini operas.

Giovanni David (15 September 1790 in Naples – 1864 in Saint

Petersburg) was an Italian tenor particularly known for his roles in

Rossini operas.David (also known as Davide) was the son of the tenor Giacomo David, with whom he studied. He made his operatic début in Siena in 1808 in Adelaide de Guesclino by Johann Simon Mayr. He is notable for the principal roles written for him by Gioachino Rossini, mostly for Domenico Barbaia's theatres in Naples:

He also created the roles of Fernando in the revised version of Bellini's Bianca e Fernando (1828) and Leicester in Donizetti's Il castello di Kenilworth (1829). David was noted for his vocal range of almost 3 octaves in performance (up to b♭′). However, according to Italian sources, David was certainly able to reach up only to F5 (and possibly to G5 or even to A5), but not higher. He was also famous for his ability to sing extremely florid music, although compared with his contemporary, Andrea Nozzari, his acting ability was limited. He retired from the stage in 1839, and subsequently managed an opera

company in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

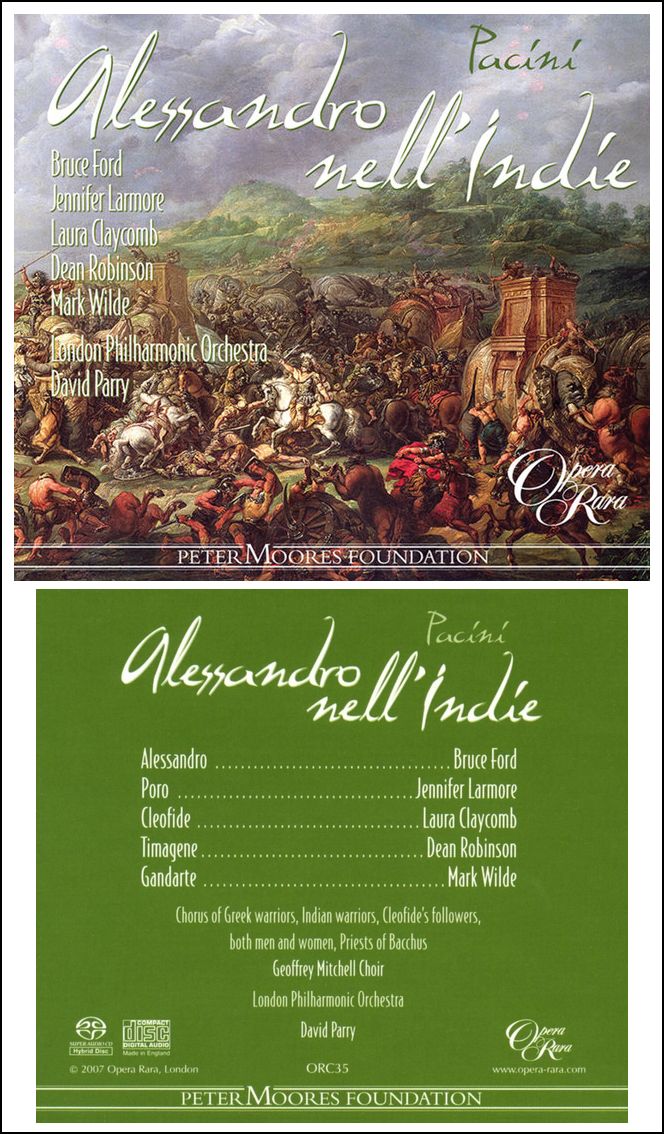

He also premièred the title roles in Giovanni Pacini's Alessandro nelle Indie (1824) and Donizetti's Alfredo il grande, and roles in operas by Michele Carafa, Manuel García, Johann Simon Mayr, Saverio Mercadante, Nicola Antonio Manfroce and Stefano Pavesi. Nozzari's voice had a baritonal quality, and his intense acting was much valued by composers and the public. Stendhal thought him one of the finest singers in Europe. Among his pupils were Antonio Poggi and Giovanni Battista Rubini. |

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 9, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1998 and twice in 1999. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.