|

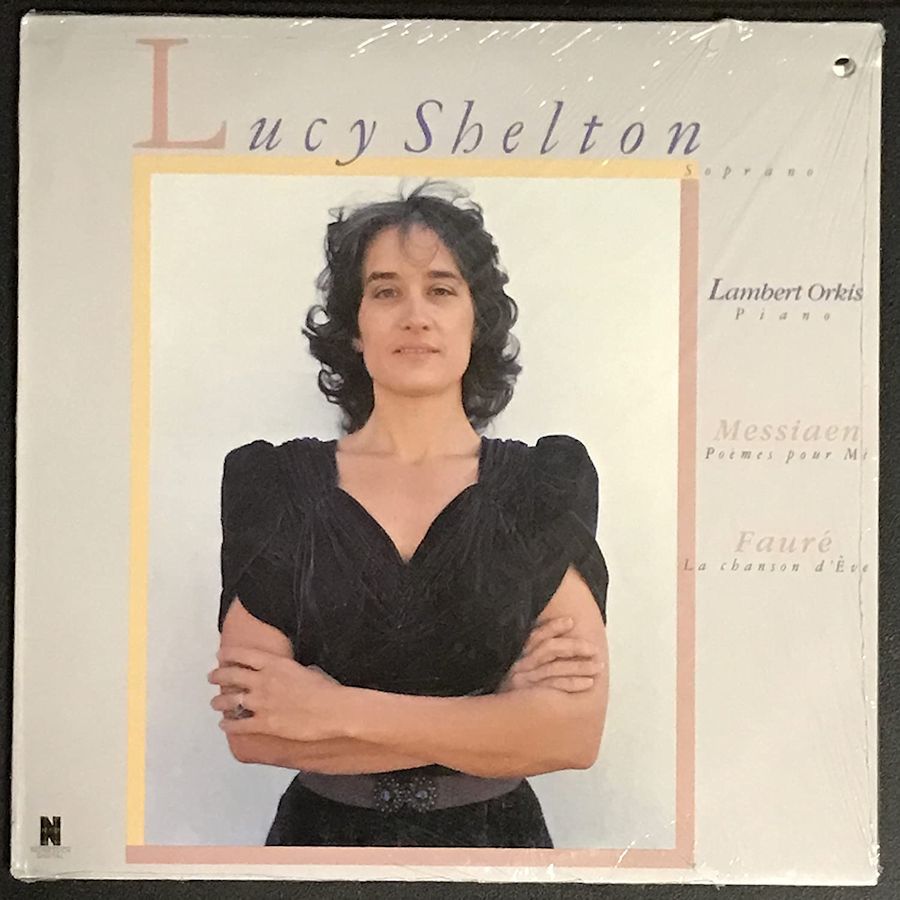

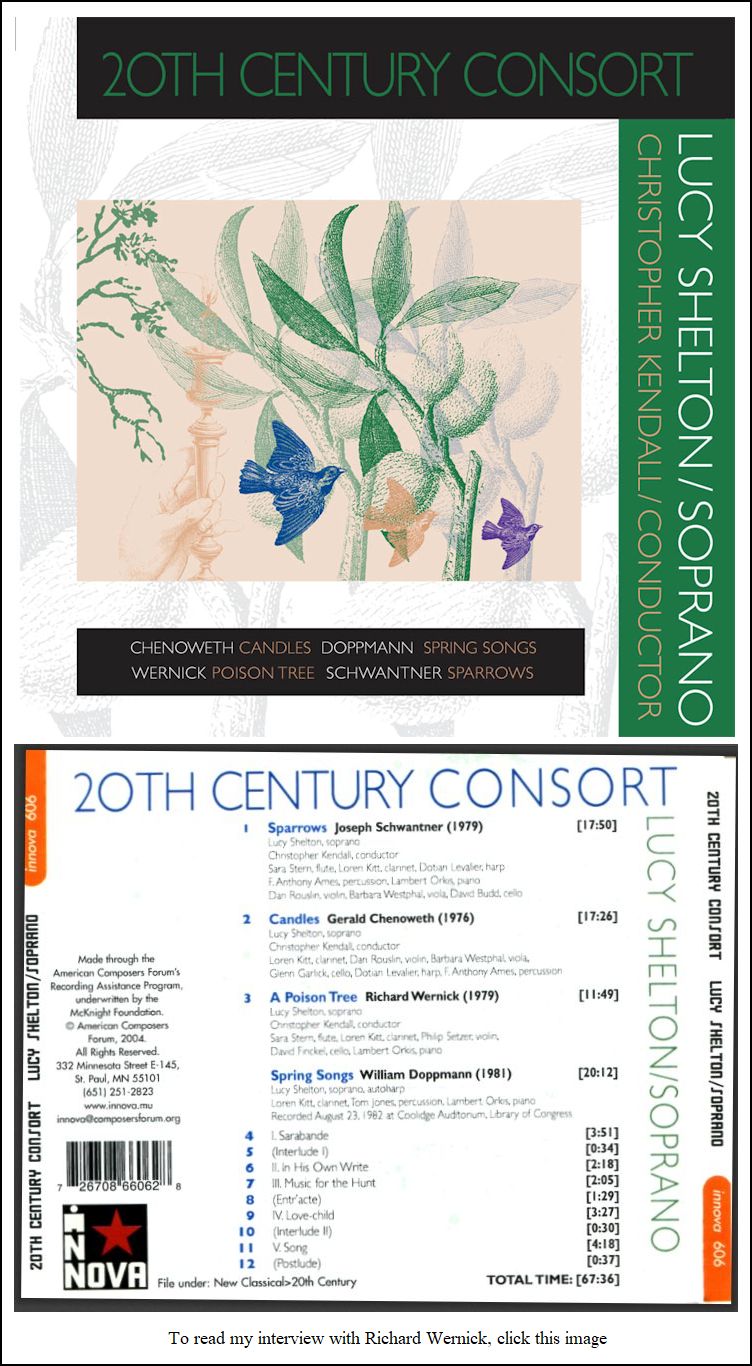

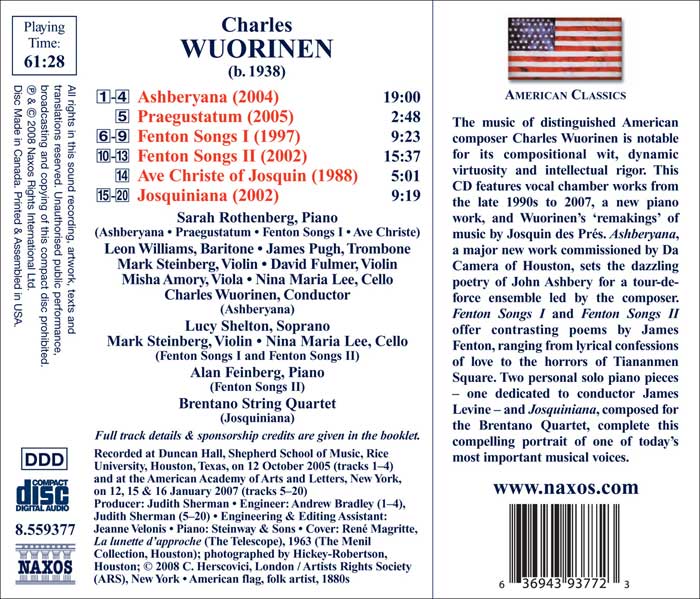

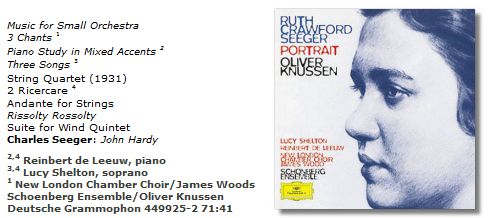

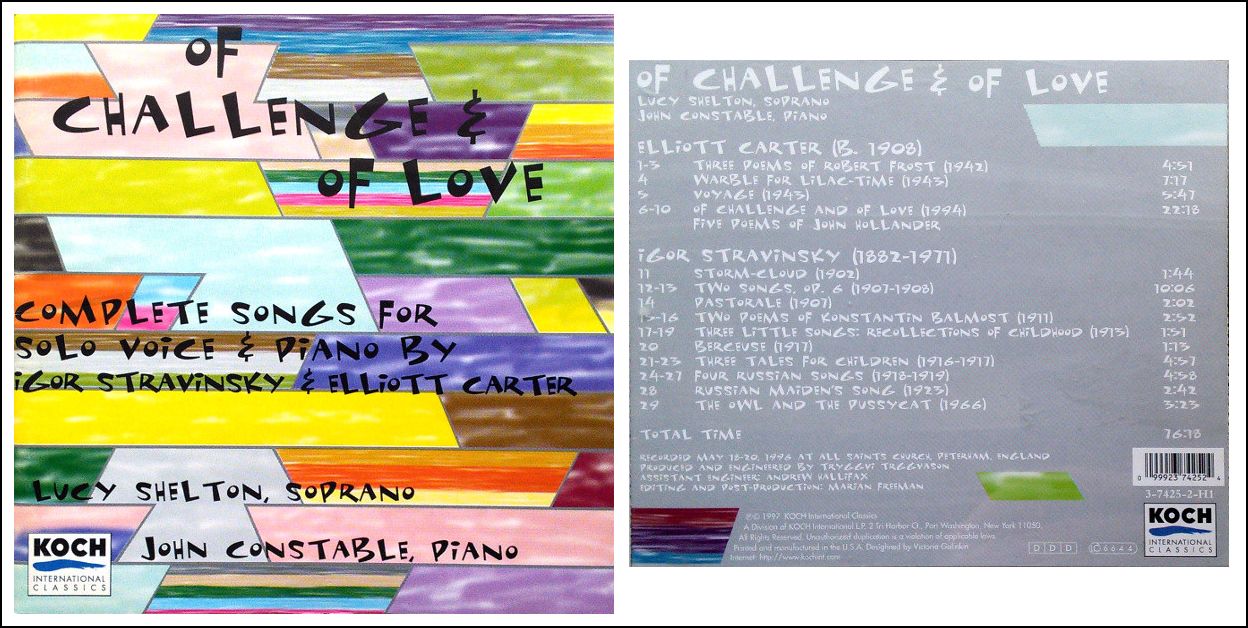

Lucy Shelton is an American soprano best known for her performance of contemporary music. She graduated from The Putney School in 1961 and Pomona College in 1965. The only artist to receive the International Walter W. Naumberg Award twice (as a soloist and as a chamber musician), Shelton has performed repertoire from Bach to Boulez in major recital, chamber and orchestral venues throughout the world. A native Californian, Shelton's musical training began early with the study of both piano and flute. After graduating from Pomona College, she pursued singing at the New England Conservatory, and at the Aspen Music School, where she studied with Jan de Gaetani. Shelton has taught at the Cleveland Institute of Music, the New England Conservatory, and the Eastman School of Music. She is currently on the faculties of the Contemporary Performance Program at the Manhattan School of Music, Tanglewood Music Center, and coaches privately at her studio in New York City. She has recorded for Deutsche Grammophon, KOCH International, Bridge Records, Unicorn-Kanchana and Virgin Classics. Shelton has appeared with major orchestras worldwide including Amsterdam, Boston, Chicago, Cologne, Denver, Edinburgh, Helsinki, London, Los Angeles, Melbourne, Minnesota, Munich, New York, Paris, St. Louis, Stockholm, Sydney and Tokyo under leading conductors such as Marin Alsop, Daniel Barenboim, Pierre Boulez, Reinbert De Leeuw, Charles Dutoit, Alan Gilbert, Oliver Knussen, Kent Nagano, Simon Rattle, Helmuth Rilling, Mstislav Rostropovich, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Leonard Slatkin and Robert Spano. Notable among her numerous world premieres are Elliott Carter’s Tempo

e Tempi and Of Challenge and Of Love, Oliver Knussen’s

Whitman Settings, Joseph Schwantner’s

Magabunda, Poul Ruders’ The Bells,

Stephen Albert’s

Flower of the Mountain, and Robert Zuidam’s opera Rage

d’Amours. She has premiered Gerard Grisey’s L’Icone Paradoxiale

with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; sung Pierre Boulez’s Le Visage

Nuptial under the composer’s direction in Los Angeles, Chicago, London

and Paris; appeared in Vienna and Berlin with György Kurtag’s The

Sayings of Peter Bornemisza with pianist Sir Andras Schiff; and made

her Aldeburgh Festival debut in the premiere of Alexander Goehr’s Sing,

Ariel.

Ms. Shelton has exhibited special skill in dramatic works, including

Luciano Berio’s

Passaggio with the Ensemble InterContemporain, Sir Michael

Tippett’s The Midsummer Marriage (for Thames Television), Luigi

Dallapiccola’s Il Prigioniero (her BBC Proms debut), Bernard Rands’ Canti

Lunatici, and recurring staged productions of Arnold Schoenberg’s

Pierrot Lunaire (with eighth blackbird and Da Camera of

Houston). Highlights of recent seasons include her 2010 Grammy Nomination

(with the Enso Quartet) for the Naxos release of Ginastera’s string quartets,

her Zankel Hall debut with the Met Chamber Orchestra and Maestro James Levine in Carter’s

A Mirror On Which To Dwell, multiple performances of a

staged Pierrot Lunaire in collaboration with eighth blackbird

and, in celebration of the work’s centenary, concert versions with 10

different ensembles worldwide. Shelton also coordinated two intense

8-day residencies at the University of Oregon (Eugene) and Southern

Illinois University (Carbondale), where she coached composers and singers

in “The Art of Unaccompanied Song”. == Names which are links in this box and below,

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Bruce Duffie: Thank you for agreeing to take a little

time out of your busy schedule.

Bruce Duffie: Thank you for agreeing to take a little

time out of your busy schedule. BD: [With a wink] You’re not

a masochist???

BD: [With a wink] You’re not

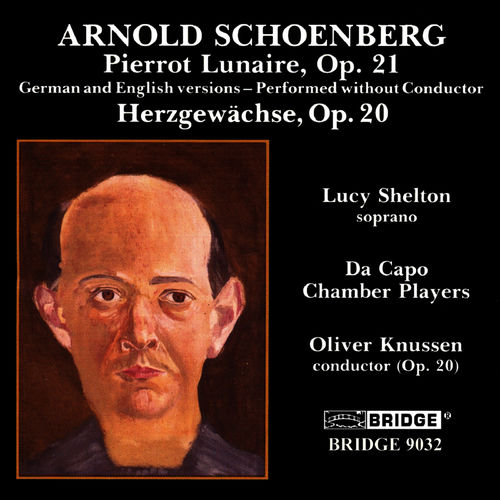

a masochist??? Shelton: Yes, I think I do, but it’s hard. The

problem with doing a recording is that whatever you were doing that day,

or those couple of days, was set and is permanent. I recently made

a recording of Pierrot Lunaire, which was really a dream. For

the singer, this work has as much room for different performances as any

piece written because of its style and because of its notation. So,

putting this down on record feels even more trepidatious, if that’s a word.

Anyway, we did the recording with some chamber players, and I got to do

twice, because we did both the German version, and one in Andrew Porter’s English

translation. There was something that felt just wonderfully relaxed

in having to try that.

Shelton: Yes, I think I do, but it’s hard. The

problem with doing a recording is that whatever you were doing that day,

or those couple of days, was set and is permanent. I recently made

a recording of Pierrot Lunaire, which was really a dream. For

the singer, this work has as much room for different performances as any

piece written because of its style and because of its notation. So,

putting this down on record feels even more trepidatious, if that’s a word.

Anyway, we did the recording with some chamber players, and I got to do

twice, because we did both the German version, and one in Andrew Porter’s English

translation. There was something that felt just wonderfully relaxed

in having to try that. Shelton: The adjustment comes with the style of the

music, and playing with five instruments instead of with an orchestra.

I don’t think of it as being something for the hall itself, it just

goes with the way the music is written. At the Proms in London,

in Albert Hall — which is one of the

biggest halls in the world [capacity is listed as 5,272]

— I did the Mallarmé Songs of Ravel,

which are about as intimate a piece of chamber music as you can find. I

had a little battle with myself, looking at this football field in front

of me, and I decided just to trust that the space would take care of what

I did. It would be foolish to think of the piece at any other dynamic

than how it was written, and my colleagues playing the instruments certainly

weren’t going to suddenly be playing a concerto. So, we continued in

our very intimate reading, and it had this wonderful hush. Everybody

had to listen, but it’s a little dangerous putting something of that size,

and making the very intimate music in such expansive place. It’s a

very live place, so it worked, but, as I say, it’s more an issue of the style

of the music. That piece wouldn’t work with a big operatic sound.

That would be out of balance with the players, so that kind of sensitivity

is very important. I do go back and forth between orchestral recitals

and chamber music, and I am always keeping those things in mind.

Here in Orchestra Hall, which is a very, very good hall [capacity listed

as 2,522], and in this piece by Boulez, Le Visage Nuptial, I’m

singing the lower part. It’s not the best, most carrying range in a

voice, so I’ll probably be singing fuller dynamics than I would ordinarily,

because it’s with full orchestra. But you also you have to trust that

the composer knew what he was doing with this piece. The work has two

female soloists, and a female chorus, and a huge orchestra. The soloists

are doubled a lot with the chorus. Phyllis [Bryn-Julson] has sung

the piece every time it’s been done so far, and she said, “Well, Boulez,

just likes it to be somewhat covered up.” We’re supposed to come

in and out of the texture of the chorus and the orchestra. That’s the

way he’s written it. If he wanted something else, then he hasn’t written

it well.

Shelton: The adjustment comes with the style of the

music, and playing with five instruments instead of with an orchestra.

I don’t think of it as being something for the hall itself, it just

goes with the way the music is written. At the Proms in London,

in Albert Hall — which is one of the

biggest halls in the world [capacity is listed as 5,272]

— I did the Mallarmé Songs of Ravel,

which are about as intimate a piece of chamber music as you can find. I

had a little battle with myself, looking at this football field in front

of me, and I decided just to trust that the space would take care of what

I did. It would be foolish to think of the piece at any other dynamic

than how it was written, and my colleagues playing the instruments certainly

weren’t going to suddenly be playing a concerto. So, we continued in

our very intimate reading, and it had this wonderful hush. Everybody

had to listen, but it’s a little dangerous putting something of that size,

and making the very intimate music in such expansive place. It’s a

very live place, so it worked, but, as I say, it’s more an issue of the style

of the music. That piece wouldn’t work with a big operatic sound.

That would be out of balance with the players, so that kind of sensitivity

is very important. I do go back and forth between orchestral recitals

and chamber music, and I am always keeping those things in mind.

Here in Orchestra Hall, which is a very, very good hall [capacity listed

as 2,522], and in this piece by Boulez, Le Visage Nuptial, I’m

singing the lower part. It’s not the best, most carrying range in a

voice, so I’ll probably be singing fuller dynamics than I would ordinarily,

because it’s with full orchestra. But you also you have to trust that

the composer knew what he was doing with this piece. The work has two

female soloists, and a female chorus, and a huge orchestra. The soloists

are doubled a lot with the chorus. Phyllis [Bryn-Julson] has sung

the piece every time it’s been done so far, and she said, “Well, Boulez,

just likes it to be somewhat covered up.” We’re supposed to come

in and out of the texture of the chorus and the orchestra. That’s the

way he’s written it. If he wanted something else, then he hasn’t written

it well.

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 6, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1994, 1998, and 1999; on WNUR in 2010, 2011, and 2019; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2010, and 2013. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.