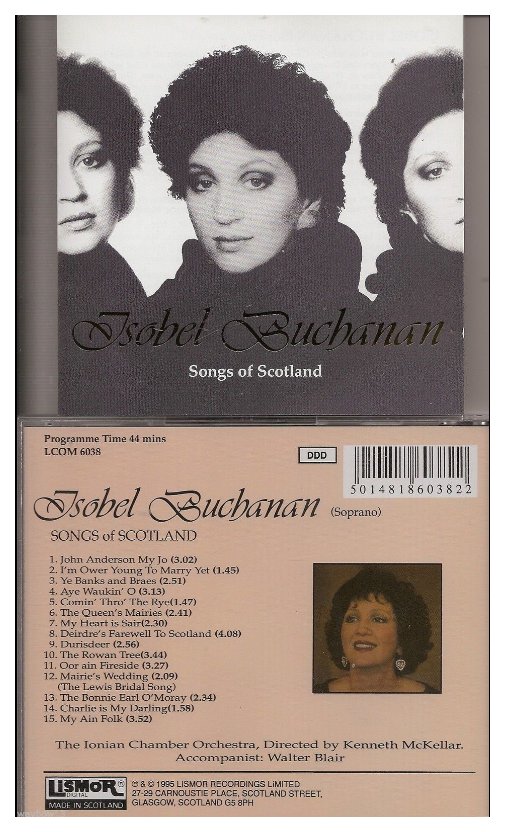

| Since entering the Royal Scottish

Academy of Music and Drama in 1971 Isobel Buchanan has become one of the

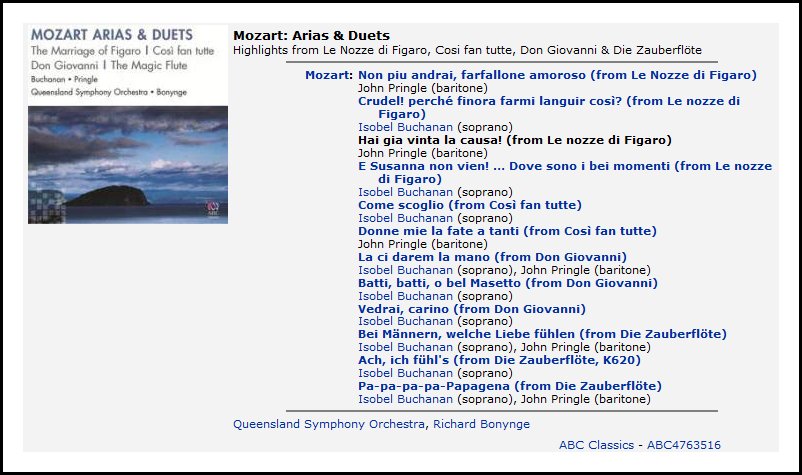

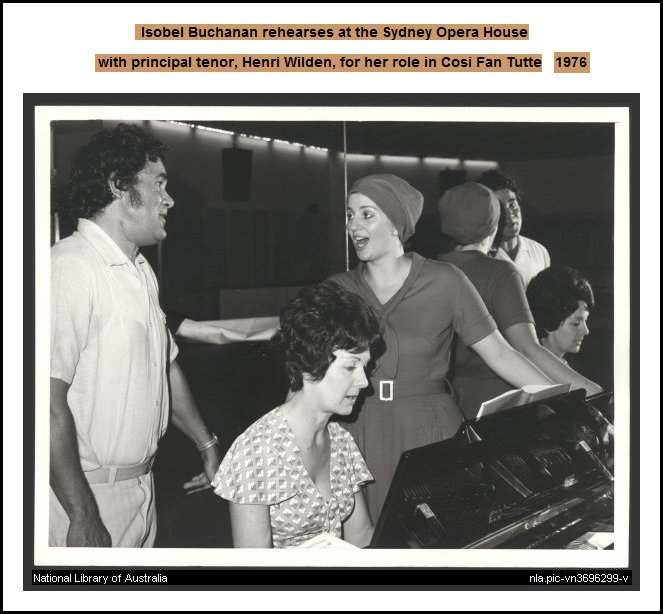

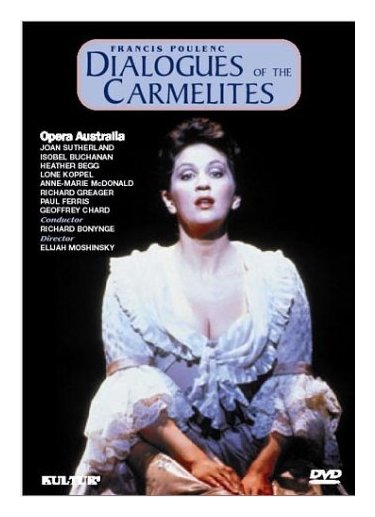

leading sopranos of her generation. In 1975 she auditioned for Richard Bonynge

and Joan Sutherland and was offered a three year contract with the Australian

Opera. Her professional debut was in January 1976, singing the role of Pamina

in Mozart's The Magic Flute, one

she was to repeat many times throughout the world. She made her British debut at Glyndebourne in 1978, again singing Pamina, in the Cox/Hockney production and in 1981 she sang the Countess in Peter Hall's production of The Marriage of Figaro, a role repeated for the 50th Anniversary of the company in 1984 with Bernard Haitink conducting. 1978 saw her as Micaëla at the Vienna State Opera in the legendary production by Franco Zefirelli, with Domingo, Obratsova and Mazurok. Conducted by Carlos Kleiber, the performance was broadcast live throughout Europe and has been released on CD and DVD. [See photo below.]

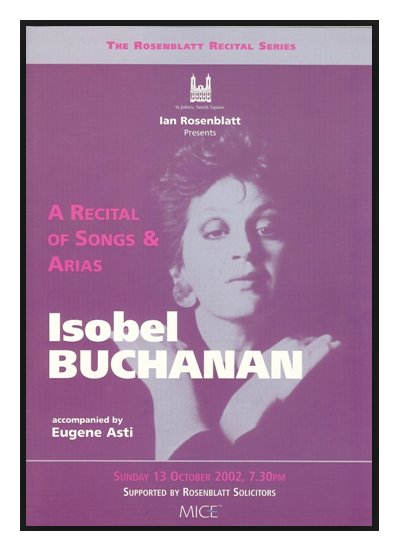

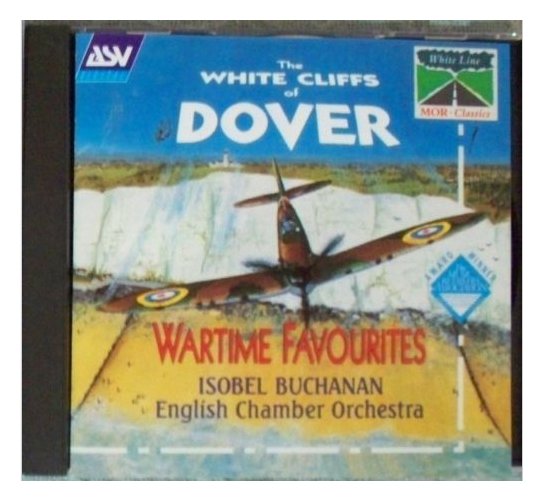

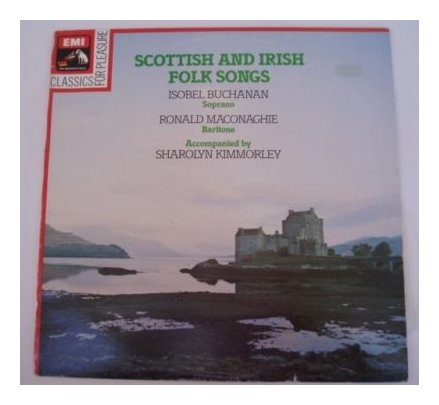

Isobel's Covent Garden debut was in Parsifal, conducted by Solti. Among other roles, she went on to sing Sophie in Werther, with Alfredo Kraus and Teresa Berganza, later recording the opera with Jose Carreras and Frederica von Stade, Sir Colin Davis conducting. She has appeared in opera houses in Cologne, Paris, Munich, Santa Fe, Brussels, Hamburg, Sydney, Wellington, Chicago (with Pavarotti and Bergonzi), and Monte Carlo (with Raimondi). She has also appeared with all the major British orchestras and has collaborated with many of the world's leading conductors, including Solti, Haitink, Andrew Davis, Colin Davis, Celibidache, Pritchard, Mariner, Kleiber and Menuhin. Isobel has made numerous recordings and in 1981 the BBC made a documentary, La Belle Isobel, of her career up to that time. She has had her own television series and has also appeared on such programmes as Face the Music and The Michael Parkinson Show. After bringing up her two daughters, Isobel has resumed her career singing recitals with Eugene Asti and Malcolm Martineau at St John's, Smith Square, as well as performing Sheherezade with the South Bank Sinfonia and Haydn with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and Walton’s Façade with Jason Thornton and the Bath Phil at Longleat. She also teaches voice privately, is a regular tutor for the Samling Foundation, gives master classes and workshops throughout the UK and teaches at the Guildhall School as a visiting professor. -- Biography from the Guildhall

School website

-- Names which are links throughout this webpage refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD |

IB: I don’t like doing one-night stands because

a lot of the enjoyment I get out of opera itself is actually the rehearsal

period. And that’s sometimes difficult because a lot of people don’t

like to rehearse. It can be hard because I think that the only way

you can get a drama together is to get to know each other and to work through

rehearsals. It’s quite hard and requires a lot of work. I don’t

mean at great length of time. It’s possible to put together a piece

of drama that would work very well in two and a half or three weeks. But

that’s quite an average rehearsal period for an opera.

IB: I don’t like doing one-night stands because

a lot of the enjoyment I get out of opera itself is actually the rehearsal

period. And that’s sometimes difficult because a lot of people don’t

like to rehearse. It can be hard because I think that the only way

you can get a drama together is to get to know each other and to work through

rehearsals. It’s quite hard and requires a lot of work. I don’t

mean at great length of time. It’s possible to put together a piece

of drama that would work very well in two and a half or three weeks. But

that’s quite an average rehearsal period for an opera. BD: How you do you decide which cantatas you will

learn or which roles you will learn? Do you wait to be asked to do

certain things, or do you learn them and hope you’ll be asked?

BD: How you do you decide which cantatas you will

learn or which roles you will learn? Do you wait to be asked to do

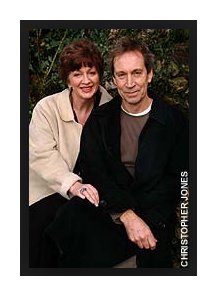

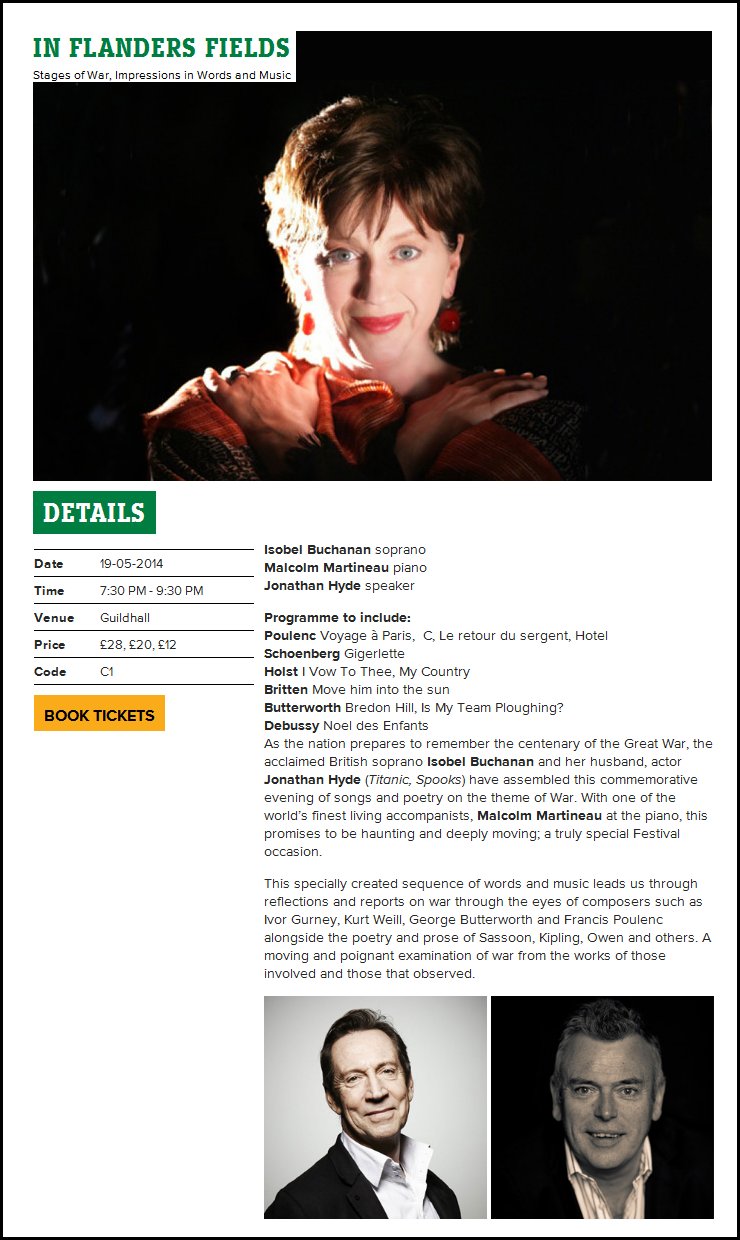

certain things, or do you learn them and hope you’ll be asked? IB: I like it mostly if my husband, Jonathan, can

come [both shown in photo at right],

and when people are around that I know. Otherwise it’s quite lonely.

IB: I like it mostly if my husband, Jonathan, can

come [both shown in photo at right],

and when people are around that I know. Otherwise it’s quite lonely.

BD: Have you sung Constanza?

BD: Have you sung Constanza? IB: Maybe it’s my kind of voice because at the moment

it is getting a little bit heavier, and maybe it’s because I have to really

make a special effort to keep it in the right focus. Somebody with

a much more coloratura-type voice could do it a lot easier. I just

find it a little bit extra work than I do, for example, in Mozart or even

Strauss, which I’m just beginning to sing. I would love to do Octavian!

IB: Maybe it’s my kind of voice because at the moment

it is getting a little bit heavier, and maybe it’s because I have to really

make a special effort to keep it in the right focus. Somebody with

a much more coloratura-type voice could do it a lot easier. I just

find it a little bit extra work than I do, for example, in Mozart or even

Strauss, which I’m just beginning to sing. I would love to do Octavian! IB: Yes, you would think so because the audience

would appreciate it more. Even in Figaro there are lots of jokes going

on, and the audience often misses them if you don’t speak the language.

That can be great, but some of it is so vile. I also did Così Fan Tutte in English, and

the translation for ‘Come Scoglio’

is hard and rock-like, which is very obscene. I remember I just couldn’t

do it without laughing. They had to change things and it was terrible.

The Magic Flute I had sent to me

was just awful with a terrible translation. I don’t even know whose

it was, so I can’t tell you. But I prefer singing in the original language

because usually the vowel sounds are made to fit whatever notes you’re singing.

So if you’re singing high, you’re not singing some ghastly vowel that’s very

hard to sing. And often that’s lost in the translation. If you

are singing something very high on an EE vowel, you’re screeching your head

off trying to do it well and you’re just totally unintelligible.

IB: Yes, you would think so because the audience

would appreciate it more. Even in Figaro there are lots of jokes going

on, and the audience often misses them if you don’t speak the language.

That can be great, but some of it is so vile. I also did Così Fan Tutte in English, and

the translation for ‘Come Scoglio’

is hard and rock-like, which is very obscene. I remember I just couldn’t

do it without laughing. They had to change things and it was terrible.

The Magic Flute I had sent to me

was just awful with a terrible translation. I don’t even know whose

it was, so I can’t tell you. But I prefer singing in the original language

because usually the vowel sounds are made to fit whatever notes you’re singing.

So if you’re singing high, you’re not singing some ghastly vowel that’s very

hard to sing. And often that’s lost in the translation. If you

are singing something very high on an EE vowel, you’re screeching your head

off trying to do it well and you’re just totally unintelligible.  IB: Sometimes it does relax everybody in rehearsal,

so it really would be interesting in performance. Sometimes the audience

is a bit hyped-up and it would be really nice if something stupid happened.

I’ve had disasters of course. My favorite one is the time I was singing

Fiordiligi. I had just done the second aria, and at that time of the

show I was tired because I was so young. I had got through the aria

and it was the best I’d done that particular night, and I was quite pleased

with myself. My exit was to go upstage center and in a flurry of excitement

rush off stage with a huge crinoline on. Well I did that, and just

as I got to center stage, I fell flat on my face, right in the middle of

the stage. I thought, “Oh God, I’m falling!” and I couldn’t do

anything to save myself. When I leaned on the dress at the front, the

crinoline went up at the back, and the audience thought it was just so funny,

they really did! They applauded for quite a long while. I thought

I’d keep it in the next time! [Both laugh] But so many things

happen on that stage that ...

IB: Sometimes it does relax everybody in rehearsal,

so it really would be interesting in performance. Sometimes the audience

is a bit hyped-up and it would be really nice if something stupid happened.

I’ve had disasters of course. My favorite one is the time I was singing

Fiordiligi. I had just done the second aria, and at that time of the

show I was tired because I was so young. I had got through the aria

and it was the best I’d done that particular night, and I was quite pleased

with myself. My exit was to go upstage center and in a flurry of excitement

rush off stage with a huge crinoline on. Well I did that, and just

as I got to center stage, I fell flat on my face, right in the middle of

the stage. I thought, “Oh God, I’m falling!” and I couldn’t do

anything to save myself. When I leaned on the dress at the front, the

crinoline went up at the back, and the audience thought it was just so funny,

they really did! They applauded for quite a long while. I thought

I’d keep it in the next time! [Both laugh] But so many things

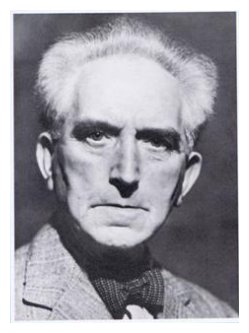

happen on that stage that ...Francis George Scott (25 January 1880

– 6 November 1958) was a Scottish composer. Born at 6 Oliver Crescent, Hawick, Roxburghshire, he was the son of a supplier

of mill-engineering parts. Educated at Hawick, and at the universities of

Edinburgh and Durham, he studied composition under Jean Roger-Ducasse. In

1925, he became Lecturer in Music at Jordanhill Training College for Teachers,

Glasgow, a post he held for more than twenty-five years.

Born at 6 Oliver Crescent, Hawick, Roxburghshire, he was the son of a supplier

of mill-engineering parts. Educated at Hawick, and at the universities of

Edinburgh and Durham, he studied composition under Jean Roger-Ducasse. In

1925, he became Lecturer in Music at Jordanhill Training College for Teachers,

Glasgow, a post he held for more than twenty-five years.He wrote more than three hundred songs, including many settings of Hugh MacDiarmid, William Dunbar, William Soutar and Robert Burns's poems. MacDiarmid stated in an essay that his key long poem A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle could not have been completed without Scott's help. The Anglo-Scottish composer Ronald Stevenson has transcribed several of Scott's works for piano. His daughter, Lillias, married the Scottish composer Erik Chisholm. * *

* * *

Francis George Scott was born in Hawick, on 25th January, Burns Day in 1880. That seems fitting for a man that set many of Robert Burns poems to music. He became one of the main exponents of the movement called the Scottish Renaissance, a flowering of Scotland’s creative talent in the inter-war years of the twentieth century, showcasing Scotland on the world stage. As a young composer his songs were compared favouably to German lieder, he was hailed as a young Mussorgsky, and he was later enticed to France where he received instruction from Jean Roger-Ducasse in 1921 but he declined his subsequent offer to stay in Paris and learn at the Paris Conservatoire, preferring instead to return to Scotland. He was a friend, teacher and mentor to Hugh MacDiarmid and helped MacDiarmid shape his masterpiece poem ‘A drunk man looks at the thistle’. Like MacDiarmid he was passionate about Scotland and he gave to the SNP his manuscript of his setting of ‘Scots wha hae’. He also set many of MacDiarmid’s poems to song. The friendship with MacDiarmid was to be a double edged sword. MacDiarmid’s frequent eulogising of Scott as one of the best composers in the world made Scott reluctant to promote his own work. -- Edited versions of two brief

biographies

|

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at her apartment in Chicago on October 14, 1981. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1985, 1988, 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.