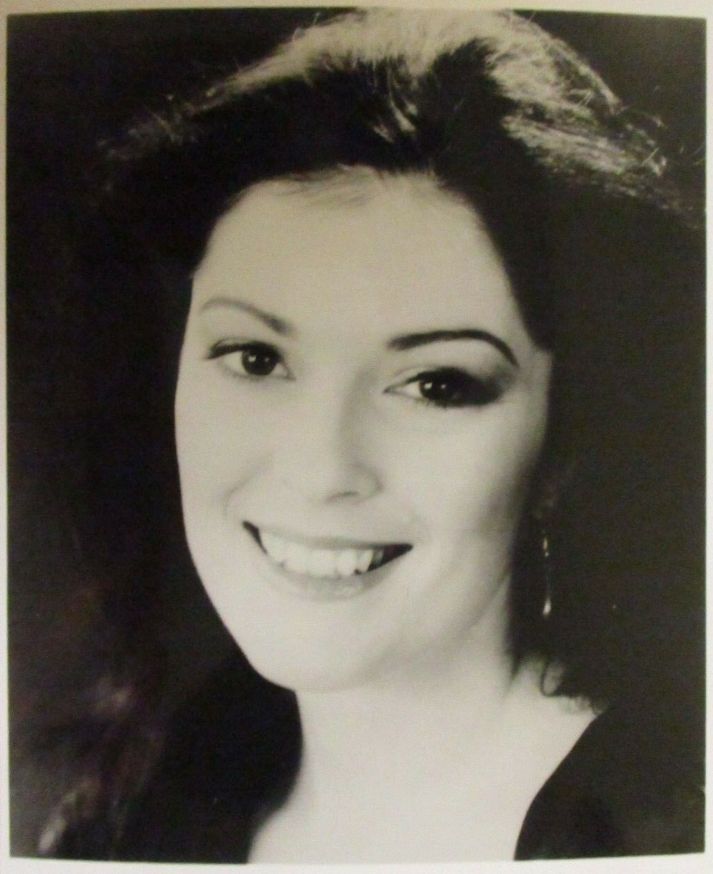

Mezzo - Soprano Jennifer Larmore

Two Conversations with Bruce Duffie

|

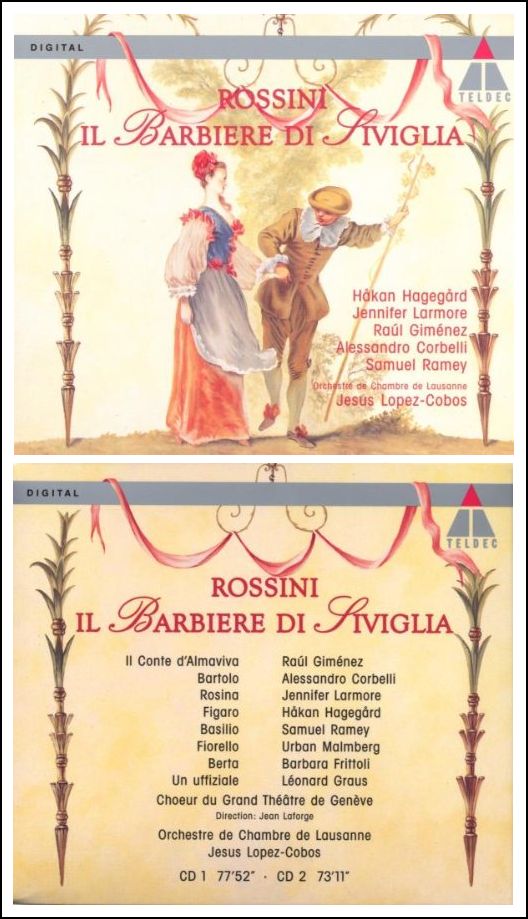

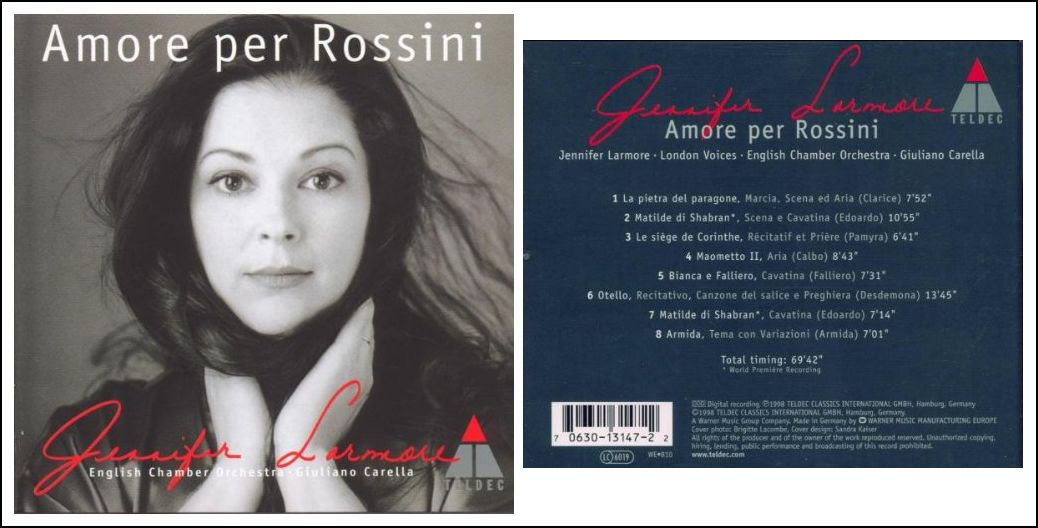

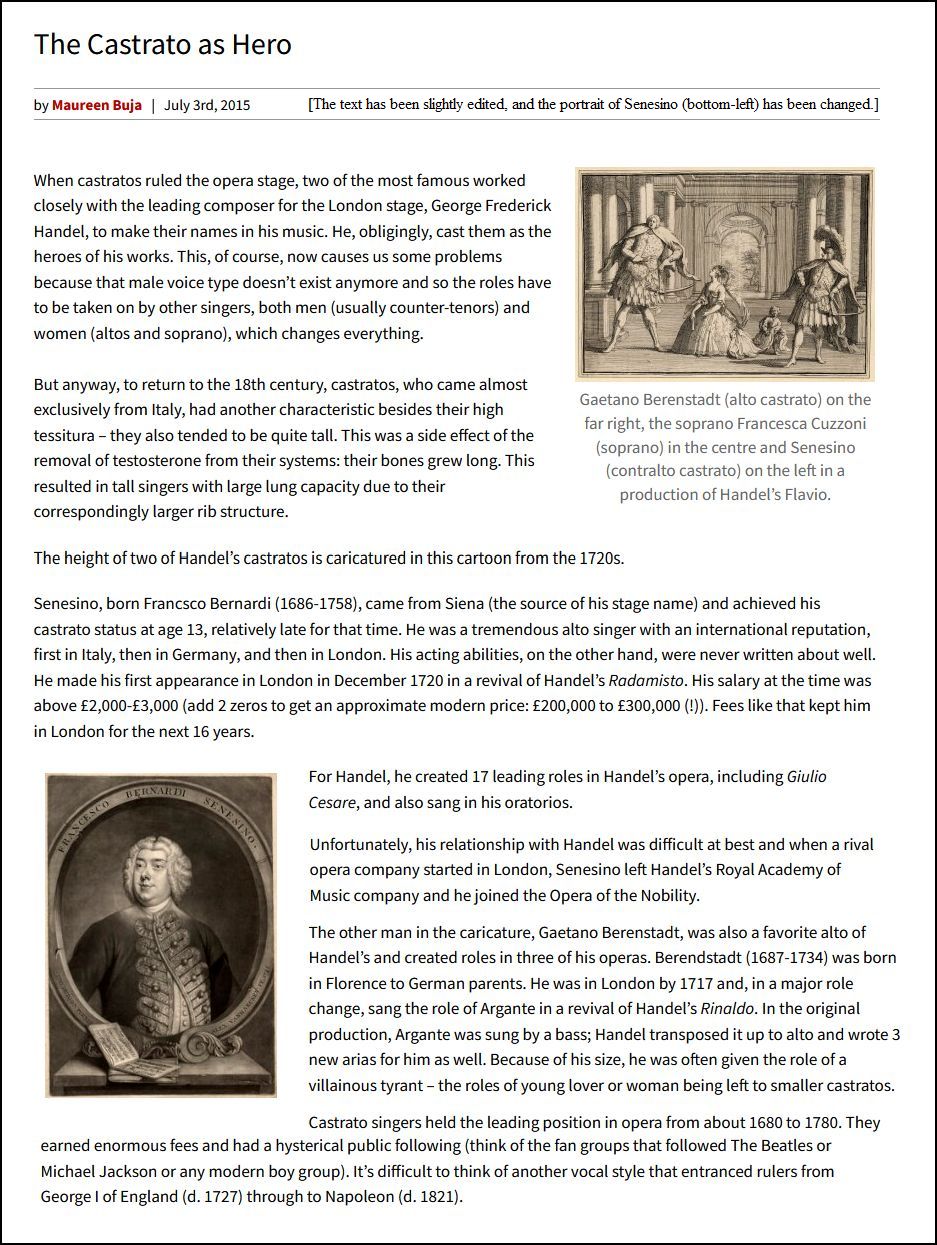

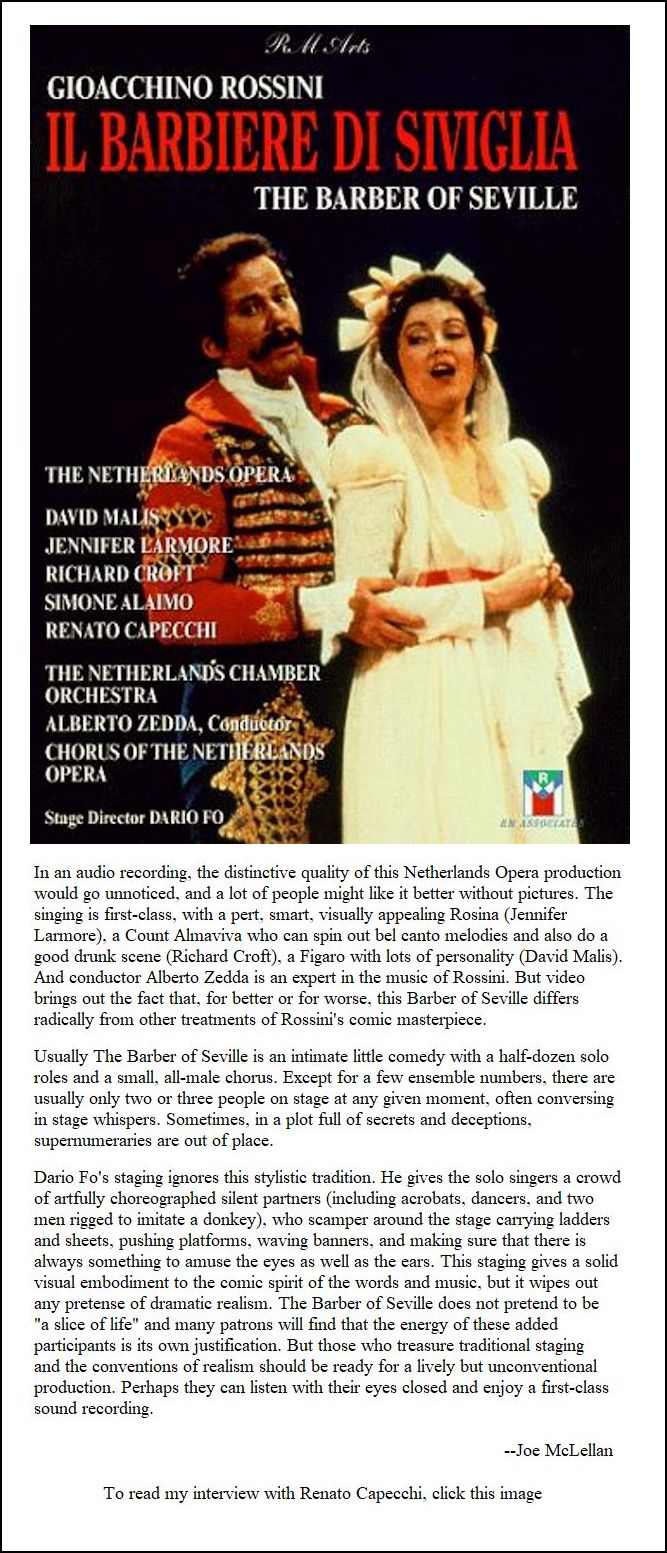

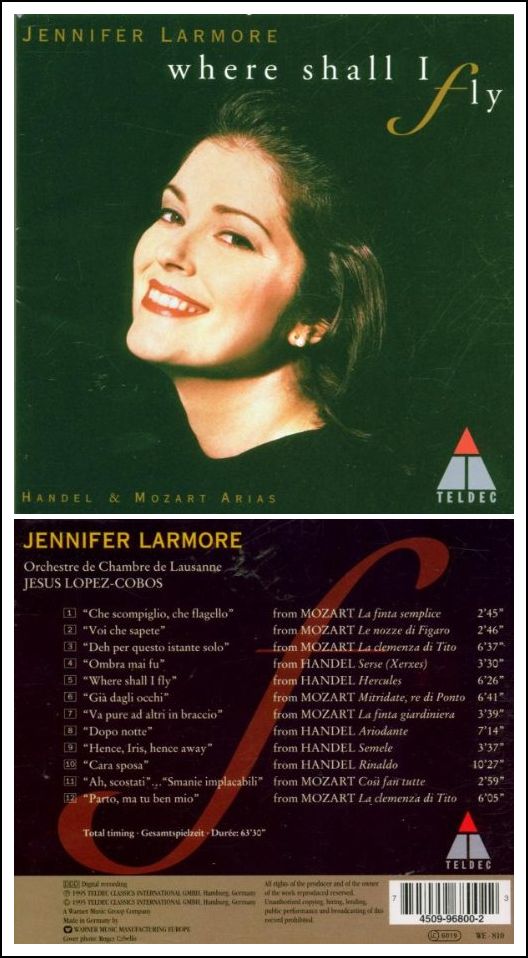

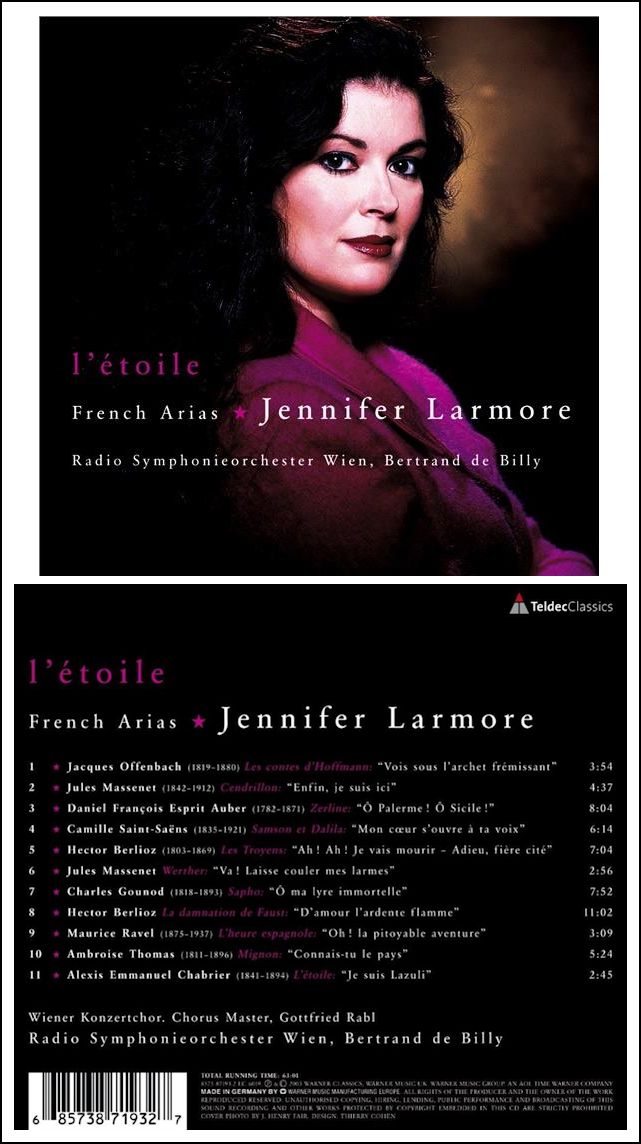

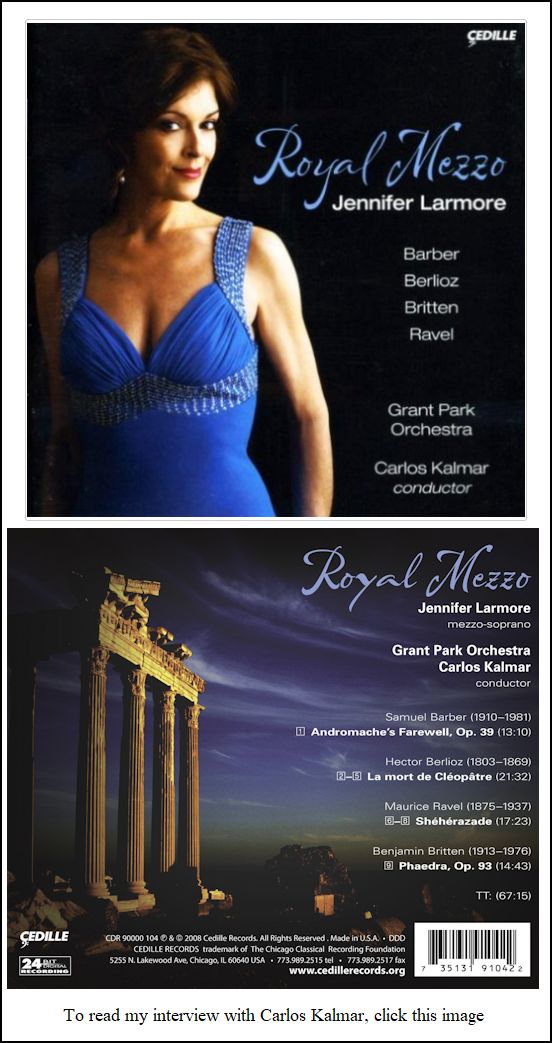

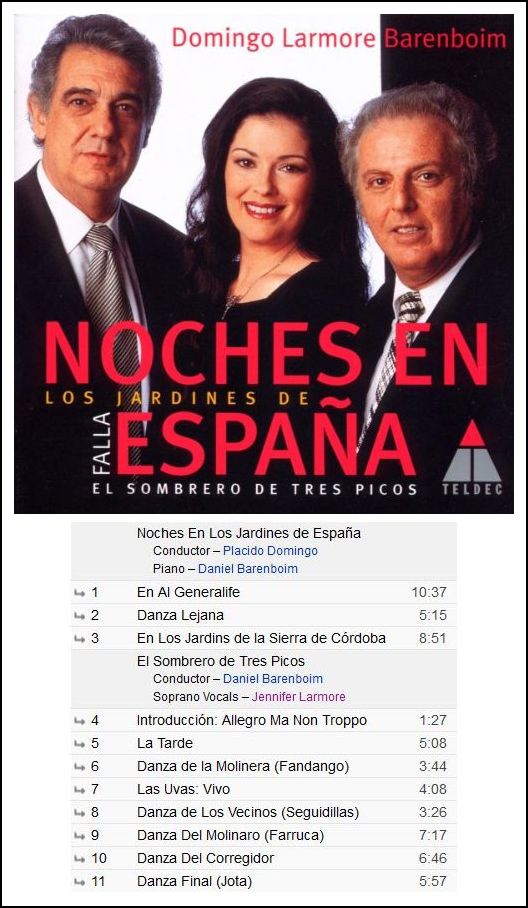

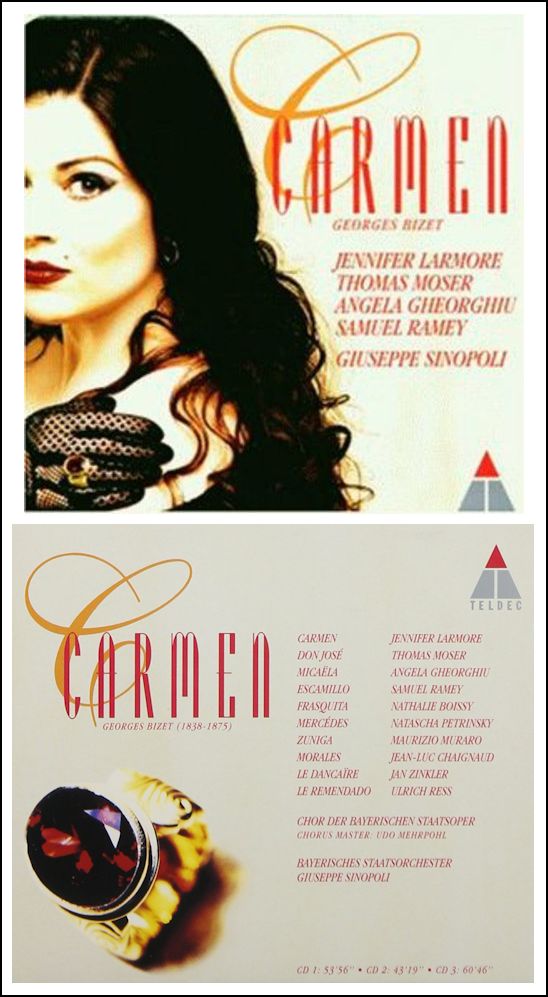

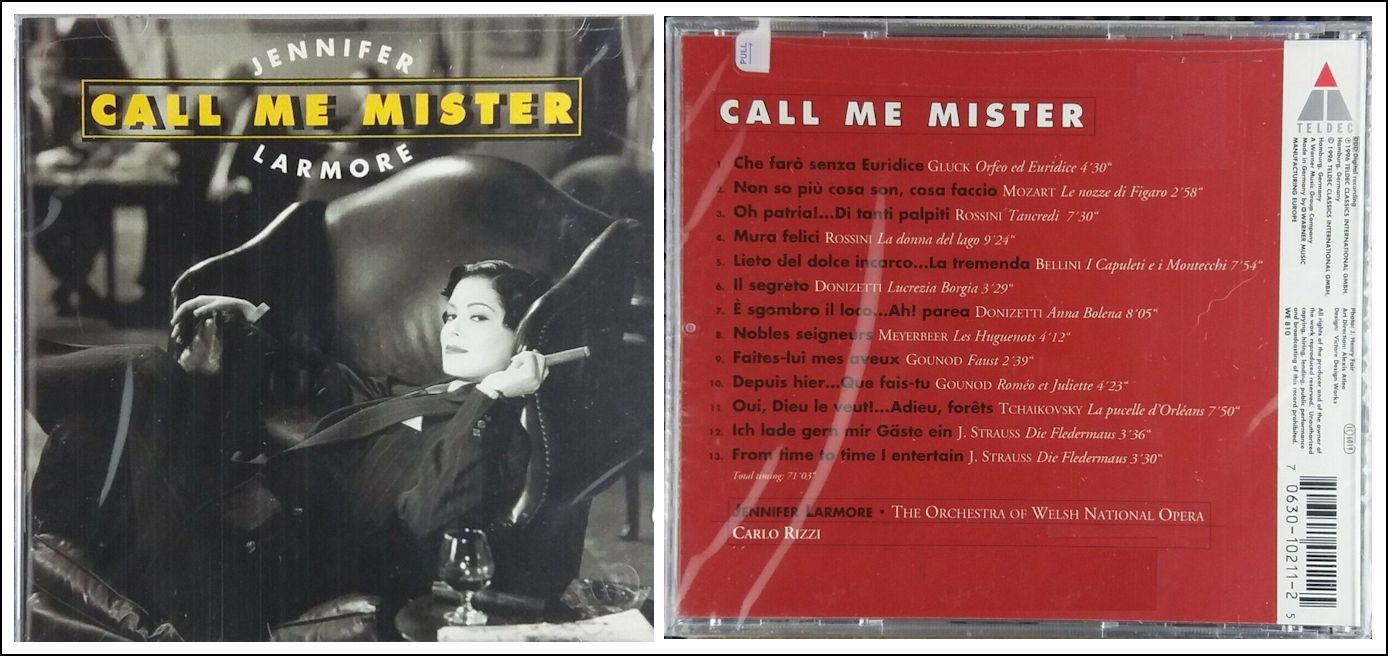

Jennifer Larmore is an American mezzo-soprano, with a wide-ranging repertoire, having begun with coloratura roles from the Baroque and bel canto then adding music from the Romantic and Contemporary periods. She began her career at Opera de Nice in 1986 with Mozart's La Clemenza di Tito, and went on to sing at virtually every major opera house in the world, including the Metropolitan Opera, La Scala, Paris Opera, Tokyo, Berlin Deutsche Oper, and London Covent Garden. She is a two-time Grammy Award winner who has recorded widely for the Teldec, RCA, Harmonia Mundi, Deutsche Grammophon, Arabesque, Opera Rara, Bayer, Naive, Chandos, VAI and Cedille labels in over one hundred CDs to date, as well as DVDs of “Countess Geschwitz” in Lulu, Jennifer Larmore in Performance for VAI, Il Barbiere di Siviglia (Netherlands Opera), L'Italiana in Algeri (Opera de Paris), La Belle Hélène (Hamburg State Opera), Orlando Furioso (Opera de Paris) and Jenůfa (Deutsche Oper Berlin). She has recorded three charming books on tape for Atlantic Crossing Records with stories by Kim Maerkl entitled Mozart's Magical Night with Hélène Grimaud and the Bavarian State Orchestra, Puccini’s Enchanted Journey with story by Kim Maerkl, and The King’s Daughter with story and music for flute and string orchestra by Kim Maerkl with the flute player Natalie Schwaabe. With the pianist Antoine Palloc, she has made many International recital tours, including appearances in Amsterdam, Paris, Madrid, Hong Kong, Seoul, Tokyo, Vietnam, Vienna, London, San Juan, Prague, Melbourne, Brussels, Berlin, Rio de Janeiro, Lisbon, São Paolo, Athens and Copenhagen, as well as all the major American venues. Symphonic repertoire has played a large role in this mezzo’s career with the works of Mahler, Schoenberg, Mozart, de Falla, Debussy, Berlioz and Barber featuring prominently. Larmore has enjoyed great collaborations with world orchestras under the direction of Muti, López-Cobos, Bernstein, Runnicles, Sinopoli, Masur, von Dohnányi, Jacobs, Rizzi, Mackerras, Spinosi, Abbado, Barenboim, Bonynge, Maazel, Ozawa and Guidarini. Jennifer’s repertoire has expanded

to include new roles such as "Marie" in Berg's masterpiece Wozzeck,

which she sang to great success at the Grand Théâtre

de Genève. Berg is now a specialty, with her having sung “Countess

Geschwitz” in Berg's Lulu at Covent Garden in the Christof Loy

production with Pappano,

then again in Madrid. At Paris Opera Bastille she sang in the Willy

Decker production, and she reprised the role yet again in a new production

of William Kentridge with Lothar Zagrosek conducting for the Nederlandse

Opera, and at the Rome Opera. She has also become well known for "Kostelnička

Buryjovka" in Janacek's Jenůfa which she performed with Donald

Runnicles at Berlin Deutsche Oper. The DVD of this production was nominated

for a Grammy. She reprised her "Kostelnička" in this same production for

the New National Theater in Tokyo. “Lady Macbeth” in Verdi’s opera

Macbeth is a role she debuted in a striking new production

of Christof Loy at the Grand Théâtre de Genève, then

in the Robert Wilson

production in Bologna and Reggio Emilia. Her first “Eboli” was in the French

version of Don Carlos at the Caramoor Music Festival in New

York, with Will Crutchfield conducting, and she sang “Jocasta” in Stravinsky’s

Oedipus Rex at the Bard Festival. Adding to her growing

list of new repertoire, Larmore debuted the role of "Mère

Marie" in Les dialogues des carmélites at the Caramoor

Festival, New York. She went back to her roots with "Ottavia" in Monteverdi's l'Incoronazione di Poppea at the Theater an der Wien in October 2015 and returned there in December 2016 for her debut in the role of "Elvira" in Mozart's Don Giovanni. Debuts for more new roles came in 2017 with the title role of La Belle Hélène at Hamburg State Opera, and then "Anna 1" in Kurt Weill's The Seven Deadly Sins for the Atlanta Opera. In 2018 she debuted the role of "La Dama" in Hindemith's Cardillac for the Maggio Musicale in Firenze, "Fidalma" In Il Matrimonio Segreto for Opera Köln, and "Marcellina" in Le Nozze di Figaro in Tokyo. Engagements in 2019 included concerts in Grenoble, Olten and Magève with OpusFive, "Marcellina" in Paris at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, and she returned to Opera Köln in the title role of a new production in her on-going collaboration with Doucet/Barbe of La Grand Duchesse de Gérolstein. 2020 was an interesting year because she debuted “Herodias” in Salome for the Atlanta Opera before going into lockdown. Continuing with their collaboration, in 2021, Jennifer sang "Genevieve" in their new production of Pelléas et Mélisande in Parma, Modena and Piacenza. She will reprise her powerful "Herodias" at the New National Theater in Tokyo in May, 2023. Larmore, in collaboration with the double bass player Davide Vittone, created an ensemble called Jennifer Larmore and OpusFive. This a string quintet offering programs that are entertaining and varied with Songs and Arias, Cabaret/Operetta and Movies and Broadway. They have given concerts in Seville, Pamplona, Valencia, Las Palmas, Venice, Amiens, Olten, Aix en Provence, Dublin, and Paris. At the Magève Festival in August, 2018 they presented a World Premiere work by composer Scott Eyerly, called Creatures Great and Small on the theme of animals. In July of 2022, Jennifer and OpusFive will perform at the Liestal Festival in a program entitled America! Throughout her career Jennifer Larmore has garnered awards and recognition. In 1994 Jennifer won the prestigious Richard Tucker Award. In 1996 she sang the Olympic Hymn at the Closing Ceremonies of the Olympics in Atlanta. In 2002, “Madame” Larmore was awarded the Chevalier des arts et des lettres from the French government in recognition of her contributions to the world of music. In 2010 she was inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame in her home state of Georgia. In addition, to her many activities, travels, performances and causes, author Jennifer Larmore is working on books that will bring a wider public to the love of opera. Her book "Una Voce" is available at Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Lulu.com and jlarmorebook.com. It explores the world of psychology of the performer. Larmore is widely known for teaching and giving master classes and in 2018, she went to New York's Manhattan School of Music, Santiago, Chile, Luxembourg, Atlanta, and to the new Teatro Nuovo at SUNY Purchase College, New York. She began the New Year 2019 with master classes for the Atlanta Opera and Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, GA. In March, 2019 Larmore gave master classes and workshops at the École Normale and for the Philippe Jaroussky Academy in Paris. In 2020 she gave classes at the École Normale, Atlanta Opera, Kennesaw State University, Luxembourg, and on ZOOM for the Kiefersfelden Master Classes and Utah Valley University. In 2022 classes will be in Malta, Tirol, Lausanne, Stockholm, Saluzzo, Martina Franca and Valencia. == Biography slightly edited from her official website == Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Isabella Angela Colbran (2 February 1785 – 7 October 1845) was a Spanish opera singer known in her native country as Isabel Colbrandt . Many sources note her as a dramatic coloratura soprano but some believe that she was a mezzo-soprano with a high extension, a soprano sfogato. She collaborated with opera composer Gioachino Rossini in the creation of a number of roles that remain in the repertory to this day. They were married on 22 March 1822. All his life Rossini credited Colbran as being the greatest interpreter of his music. Descriptions of Colbran's voice characterise the timbre as "sweet, mellow" with a rich middle register. Rossini's music for her suggests perfect mastery of trills, half-trills, staccato, legato, ascending and descending scales, and octave leaps. Her vocal range extended from F-sharp below the staff to E above, with a high F sometimes available. |

Mary Garden, (born Feb. 20, 1874, Aberdeen, Scotland—died Jan. 3, 1967, Aberdeen), soprano famous for her vivid operatic portrayals. She was noted for her acting as well as her singing and was an important figure in American opera. Garden went to the United States from Scotland with her parents when she was seven and began studying violin and piano and receiving voice lessons at an early age. In 1897 she traveled to Paris to continue her voice training. A soprano, she made her public debut there in April 1900 in Gustave Charpentier’s Louise at the Opéra-Comique when, as understudy, she filled in for the stricken regular soprano. She was an immediate success and subsequently sang in La traviata and other operas. In April 1902 she was chosen by Claude Debussy to sing the female lead in the premiere of his Pelléas et Mélisande at the Opéra-Comique, and her interpretation of that role became her most famous. == Text from Britannica.com

|

| [From a performance review nearly

twenty years later...] As Charlotte, Jennifer Larmore sang (and looked) like a mezzo half her age. If there’s a more focused edge to the sound now than there used to be, it was effective in emphasizing the character’s backbone. And the voice is still a beautiful one, with plenty of velvet in the lower register to fill out the phrases of her emotionally complex music in Act Three, writing that brought out her skills as a fine, word-sensitive singing-actress as well. == Joe Banno, Washington Post, May 23, 2011

|

© 1992 & 1996 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on September 25, 1992, and September 2, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, and 1998. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.