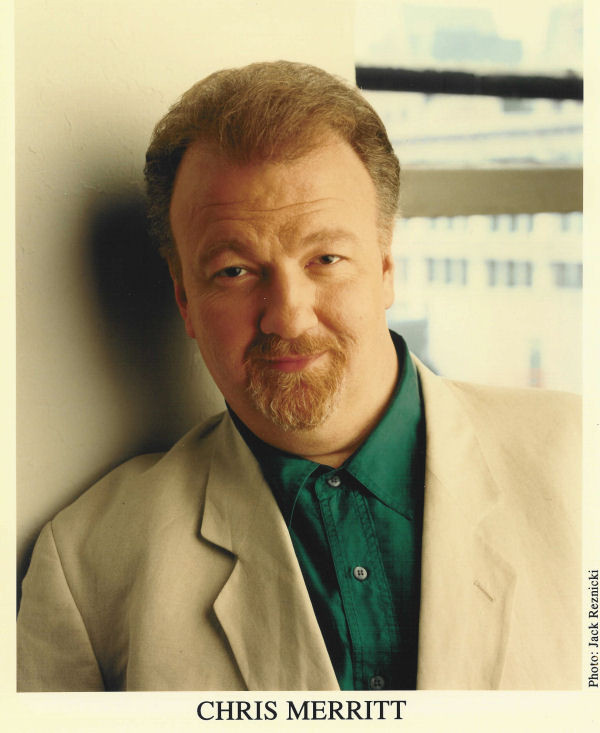

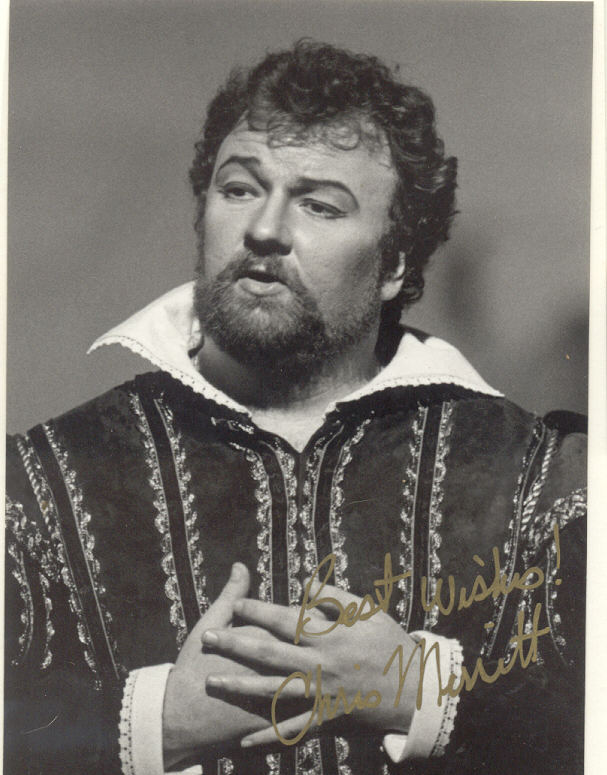

| Chris Merritt was born in Oklahoma City

on September 27, 1952 and began singing lessons at the age of

15, making his operatic debut in an Oklahoma City University

student production of Douglas Moore’s The Ballad of Baby Doe

two years later. He entered the training program at The Santa Fe

Opera at 21, and made his professional debut in Verdi’s Falstaff

(Dr Caius) in 1975; throughout the late 1970s he performed regularly

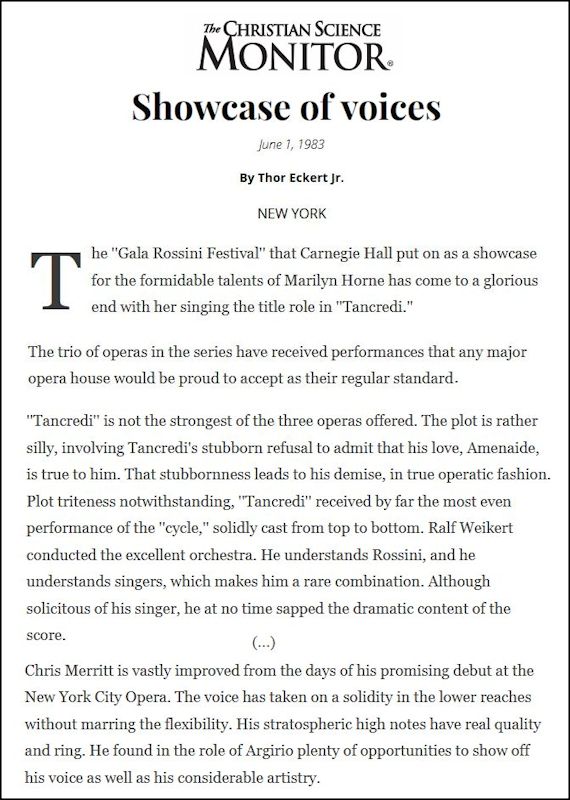

in Germany and Austria, and from the early 1980s began to attract

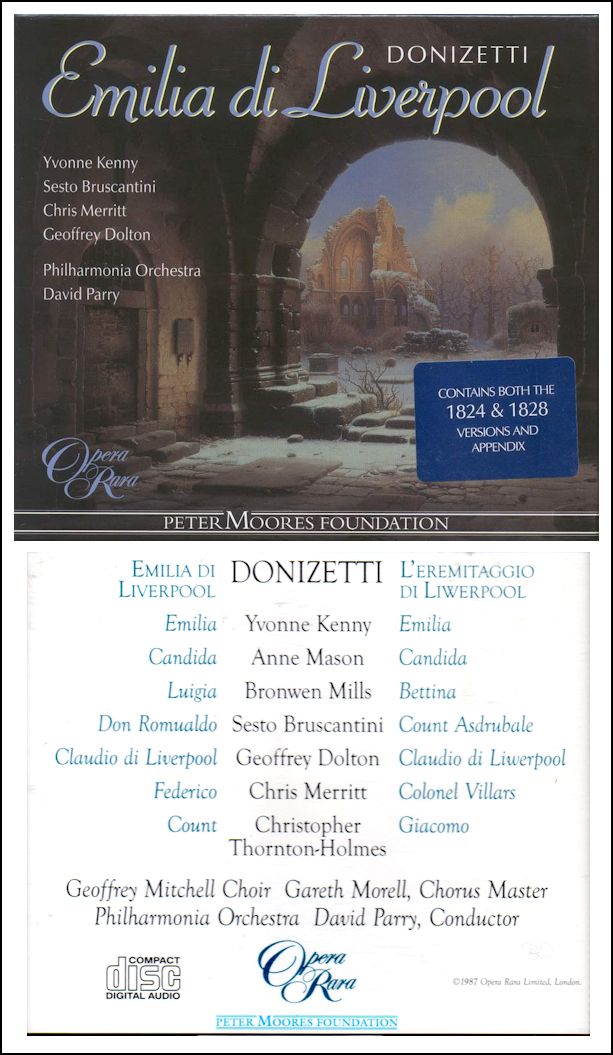

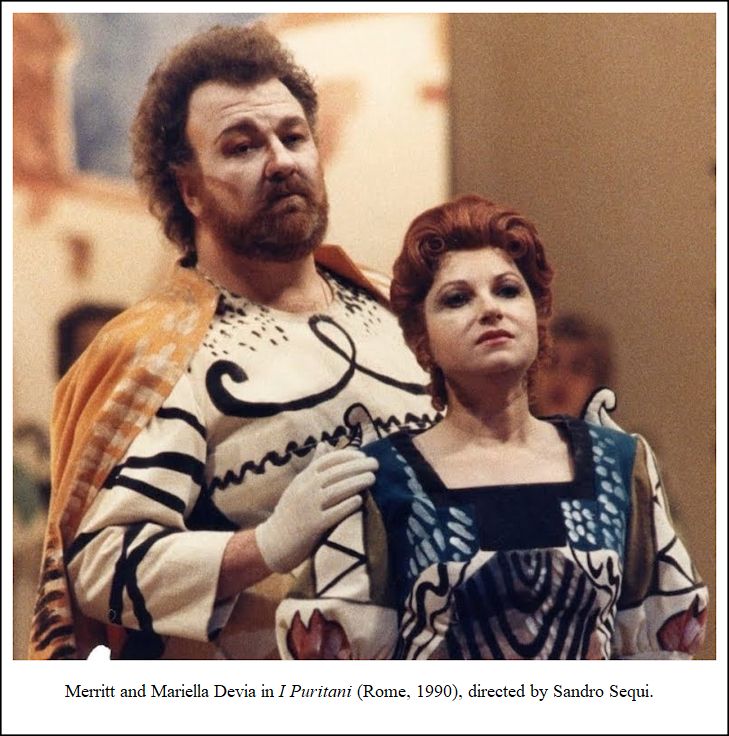

considerable attention for his affinity with high-lying bel canto

roles such as Arturo in I puritani, Argirio in Tancredi

(which he sang opposite Marilyn Horne at Carnegie Hall), and Idreno

in Semiramide, with which he made his Metropolitan Opera debut

in 1985. Following a series of professional setbacks which led to

him crowdfunding an audition tour in 2015, Merritt resumed a successful

career in character-roles such as Herodes in Strauss’s Salome,

Emperor Altoum in Puccini’s Turandot and the Witch

in Humperdinck’s Hansel und Gretel. A more detailied biography can be found at the bottom of this webpage. == Names which are links refer to my interviews

elsewhere on my website. BD

|

BD: Did you decide to go into opera or Broadway,

or did the voice decide that for you?

BD: Did you decide to go into opera or Broadway,

or did the voice decide that for you? BD: Is it right to consider you a Rossini Tenor?

BD: Is it right to consider you a Rossini Tenor? BD: What about those non-commercial

recordings? [Remember, this interview was held in 1985,

before he had made most of his commercial discs.]

BD: What about those non-commercial

recordings? [Remember, this interview was held in 1985,

before he had made most of his commercial discs.] BD: We’ll see. We’ll do another interview

in fifteen years. [As it turned out, we met again eight

years later, and that conversation is included on this webpage.]

Are you conscious of the fact that you are one of the few tall tenors

around?

BD: We’ll see. We’ll do another interview

in fifteen years. [As it turned out, we met again eight

years later, and that conversation is included on this webpage.]

Are you conscious of the fact that you are one of the few tall tenors

around?

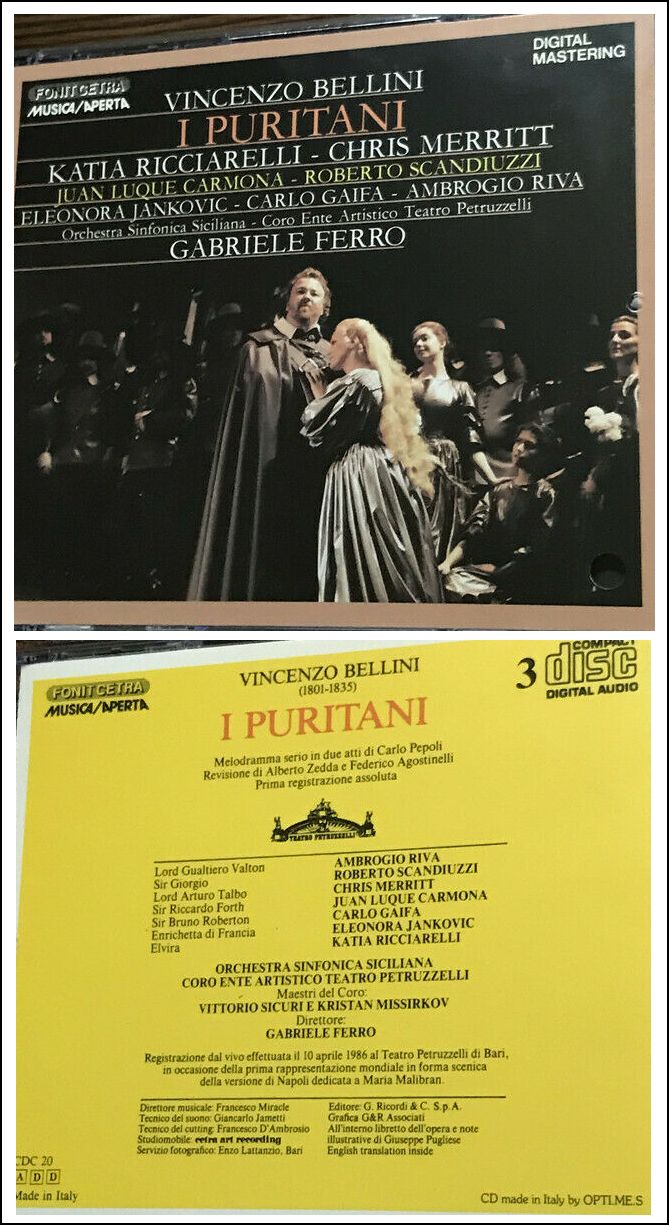

Chris Merritt

at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1985-86 - Anna Bolena (Percy) with Sutherland, Toczyska, Zilio, Plishka, Doss; Bonynge, Mansouri, Schuler 1988-89 - Tancredi (Argirio) with Horne, Cuberli, Cox, Redmon, Sharon Graham; Bartoletti, Copley, Conklin, Schuler 1990-91 - [Opening Night] Alceste (Admète) with Norman, Doss; Bertini, Wilson, Tallchief 1991-92 - I Puritani (Arturo) with Anderson, Plishka/Kavrakos, Maultsby, Coni; Renzetti, Sequi, Schuler 1992-93 - [Opening Night] Otello [Rossini] (Otello) with Cuberli, Croft, Blake, Maultsby, Runey; Renzetti, Pizzi/Tessitore, Schuler 1993-94 - Trovatore (Manrico) with Kazarnovskaya, Zajick, Gavanelli, Langan; Richard Buckley, Frisell, Benois, Schuler |

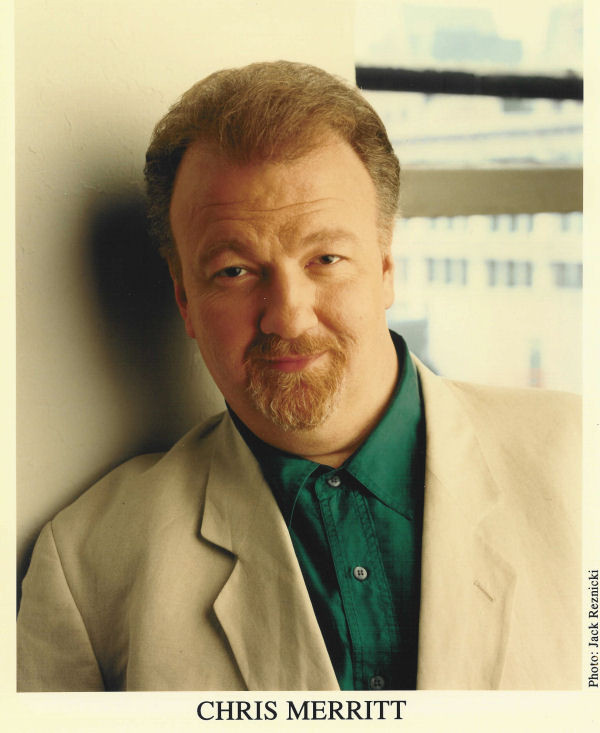

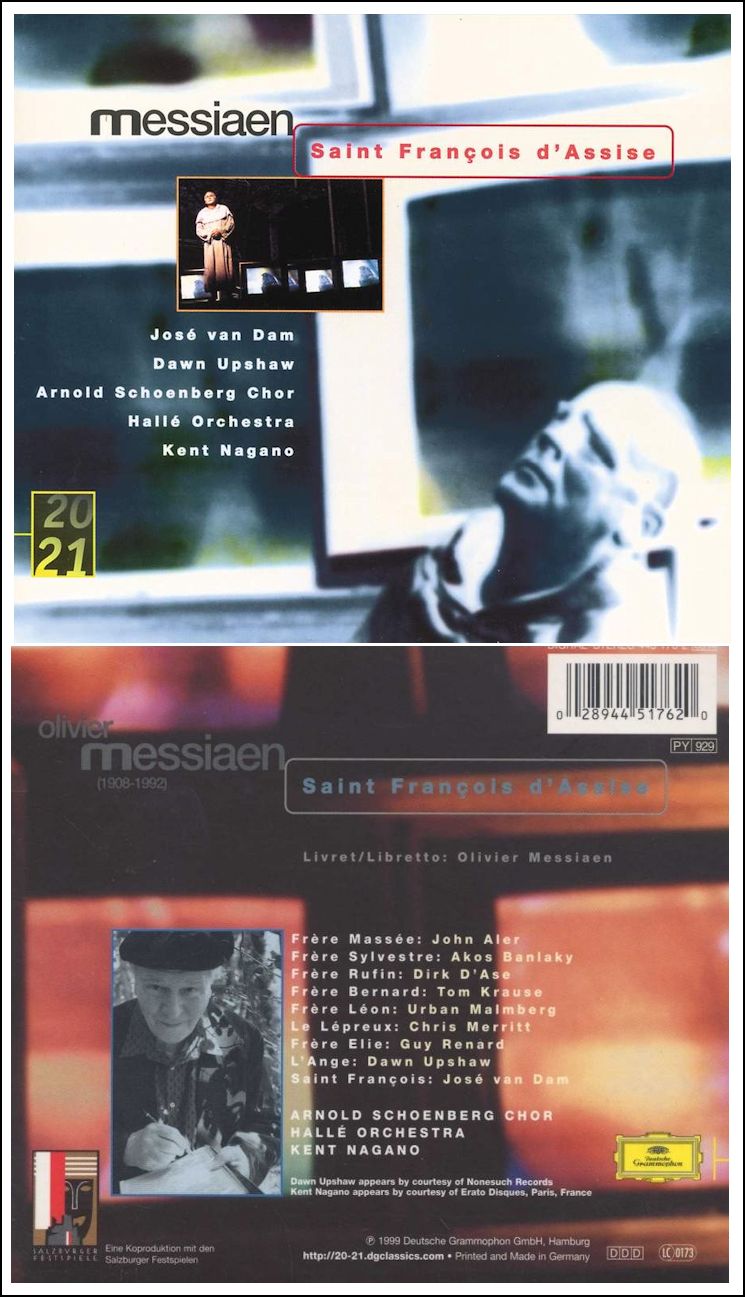

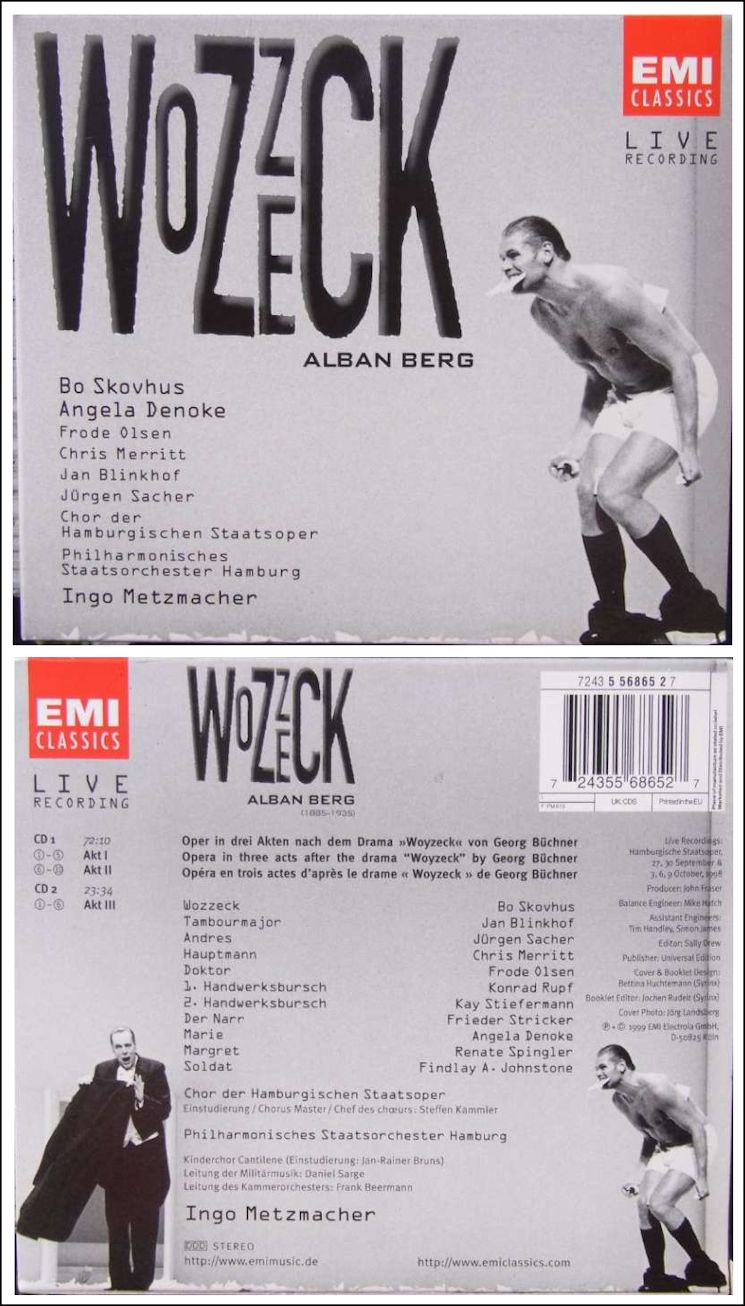

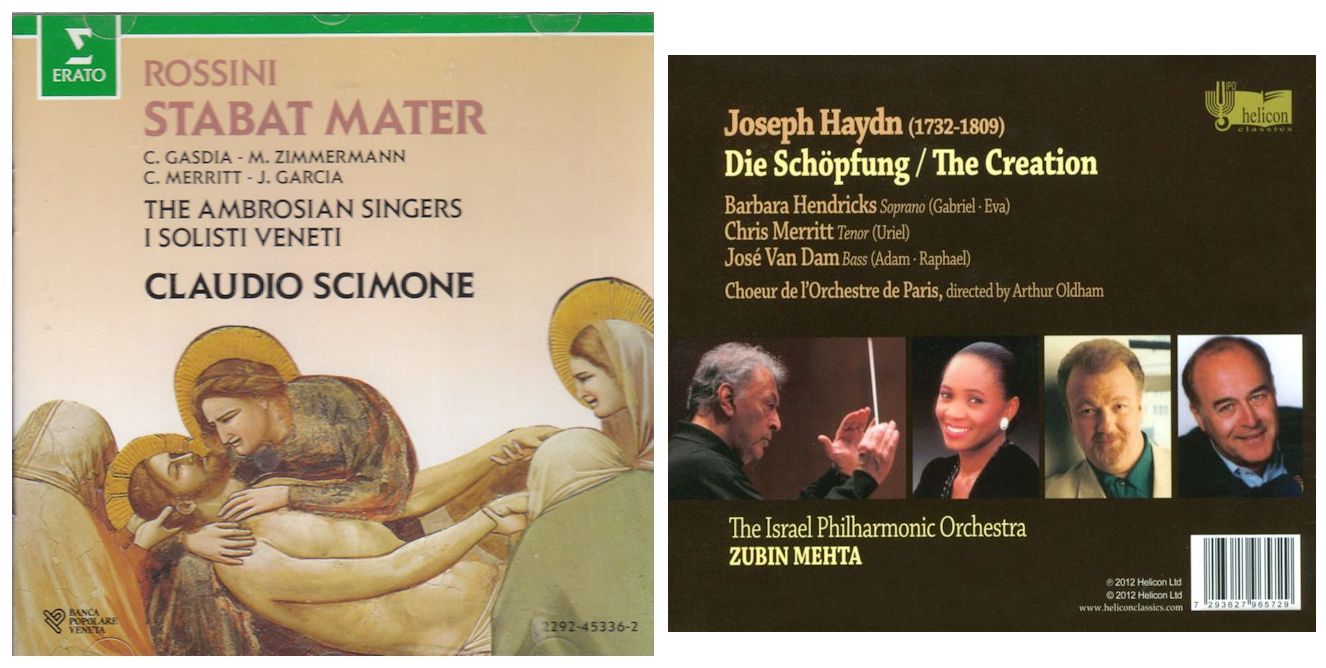

BD: What adjustments do you make for a small house

to a medium-sized house to a large house? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at left, see my interviews with José van Dam, Dawn Upshaw, John Aler, and Tom Krause.]

BD: What adjustments do you make for a small house

to a medium-sized house to a large house? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at left, see my interviews with José van Dam, Dawn Upshaw, John Aler, and Tom Krause.] BD: We’ve had him here almost

every year for twenty years, and it’s been wonderful.

BD: We’ve had him here almost

every year for twenty years, and it’s been wonderful.|

Born in Romano di Lombardia, Rubini began as a violinist at twelve years of age at the Teatro Riccardi in Bergamo. His first appearance as singer was 1814 in Pavia in Le lagrime d'una vedova by Pietro Generali. After ten years spent in Naples between 1815 and 1825, during which he also scored spectacular successes in France in the 1825/26 season in operas by Rossini, he moved permanently to Paris, performing in La Cenerentola, Otello, and La donna del lago. He divided his time between Paris (in the Autumn and Winter) and London (in the Spring). His special relation with Vincenzo Bellini began with Bianca e Fernando (1826) and continued until I puritani (1835), when he was one of the long-remembered "Puritani quartet" for whose voices the opera was written. The three other members of the illustrious quartet were Giulia Grisi, Antonio Tamburini and Luigi Lablache. The four appeared together again in Donizetti's Marino Faliero during the same season, then travelled to London with the Irish composer Michael William Balfe for a further round of operatic engagements. Rubini was admitted as an honorary member of the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna, and retired with a great fortune in 1845. He died in his hometown of Romano in 1854, and is buried in the cemetery there, within a large marble monument. |

BD: What do you do with the other thirty percent?

BD: What do you do with the other thirty percent?| Adolphe Nourrit (3 March

1802 – 8 March 1839) was a French operatic tenor, librettist, and composer.

One of the most esteemed opera singers of the 1820s and 1830s, he

was particularly associated with the works of Gioachino Rossini and

Giacomo Meyerbeer. Nourrit was raised in Montpellier, Hérault. His father, Louis Nourrit, was a well-known operatic tenor and diamond merchant. Louis' example deeply influenced Adolphe (and Adolphe's brother Auguste, who would also become a tenor). Adolphe studied singing and musical theory with his father and then, despite his father's objections, took lessons with Manuel del Pópulo Vicente García. He began his performing career shortly after finishing his studies with García, which lasted for 18 months. Not yet 20 years of age, Adolphe Nourrit made his professional operatic debut in 1821 as Pylades in Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride, being welcomed by his father performing the tiny role of a Scythian. In 1826, he succeeded Louis as the principal tenor at the Paris Opéra, a position he held until 1836.

Nourrit was an intelligent and cultured singer. He possessed a mellow and powerful vocal timbre during his prime, and was a master of the head voice. His range extended up to E5, although he never went higher than D5 in public. He sang during a turning-point in French operatic vocalism, when performers began using a rounder, more open-throated and Italianate method of voice production than hitherto had been the case, with less resort to falsetto by tenors. Indeed, the scores of the musical passages written for Nourrit by Rossini, Meyerbeer and others, contain orchestral markings which indicate that he could not have been singing in falsetto in his upper register. This was a departure from the practice of earlier male operatic interpreters. As Nourrit's status at the Opéra increased, so did his influence upon new productions. Composers often sought, and usually accepted, his advice. For example, when it came to La Juive, he wrote the words of Eléazar's aria "Rachel, quand du Seigneur", and he also insisted that Meyerbeer rework the love-duet climax of Act 4 of Les Huguenots until it met with his approval. While at the Opéra, Nourrit received consistent positive reviews for his performances, and his popularity led to his appointment as the professeur de déclamation pour la tragédie lyrique at the Conservatoire de Paris in 1827. He had many successful students, including the dramatic soprano Cornélie Falcon. [She and Nourrit are credited with being primarily responsible for raising artistic standards at the Opéra, and the roles in which she excelled came to be known as "falcon soprano" parts. For more about Falcon, see my interview with Lucia Valentini Terrani.] In addition, he was concerned more broadly with the social aspects of singing, particularly with the "missionary" role of the performer. In the early 1830s, he embraced the ideas of Saint-Simonianism, and dreamed of founding a grand opéra populaire which would introduce operatic works to the masses. Beside singing and teaching, Nourrit composed and wrote scenarios for ballets at the Opéra de Paris, including the libretto for La Sylphide (1832). Nourrit's fame faded in the late 1830s, however, as new singers gained the favour of the Parisian public. In October 1836, impresario Duponchel engaged Gilbert Duprez, who commanded an exciting high C from the chest, as joint "First Tenor" with Nourrit at the Opéra de Paris. Nourrit accepted this arrangement as a hedge against his falling ill. He sang his Guillaume Tell part exceptionally well with Duprez in the audience on 5 October 1836 but five days later, during La muette de Portici, with Duprez again in the house, he suddenly went hoarse. After the performance, Hector Berlioz and George Osborne walked Nourrit up and down the streets as he despaired aloud and talked of suicide. On 14 October, he resigned from the Opéra. Throughout this vexed period in his life, Nourrit enjoyed success as a recitalist. He was the first to introduce Franz Schubert's lieder to Parisian audiences at the celebrated soirées organized by Franz Liszt, Chrétien Urhan, and Alexandre Batta at the Salons d’Erard in 1837. The intimacy of the salon apparently suited him well, and although criticized for a weakening voice, his singing displayed impressive nuances of feeling and a wide dramatic range. His farewell performance at the Opéra happened on 1 April 1837. He embarked immediately on a tour of the provinces, but a liver ailment (possibly caused by alcoholism) forced him to cut short this venture. While listening to Duprez at the Opéra on 22 November 1837, he decided to go to Italy in the hope of mastering the Italian manner of singing in order to succeed the great Italian virtuoso tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini when Rubini retired from the stage. He duly left Paris in December of that year. The following March, he began studies in Naples with the composer Gaetano Donizetti, who was a friend of Duprez. He also asked Donizetti to provide an opera for his début in Naples. Donizetti complied, but the new work, Poliuto, was banned from performance on the secular stage by the authorities because of its Christian subject matter, and Nourrit felt betrayed. Meanwhile, he had been working hard to eradicate excessive nasal resonance from his tone production, only to lose his head voice as a result. His wife, arriving in Italy in July 1838, was shocked by what she considered to be the impaired sound of his singing, and by the fragile state of his physique. He was being leeched regularly, and was constantly hoarse. Nonetheless, his delayed Neapolitan début, which took place in Saverio Mercadante's Il giuramento on 14 November 1838, proved to be a success. As Nourrit's liver disease worsened, so did his mental state, and his memory began to fail as well. On 7 March 1839 he sang at a benefit concert but was disappointed by the quality of his performance and the audience's reaction to it. The following morning, he jumped to his death from the Hotel Barbaia. His body was returned to Paris for burial. At Marseilles, while the body was in transit to Paris, Frédéric Chopin played an organ transcription of Schubert's lied Die Gestirne at a memorial service. He is buried in Montmartre Cemetery with his wife, who survived

him by only a few months, dying shortly after the birth of their

youngest son. |

|

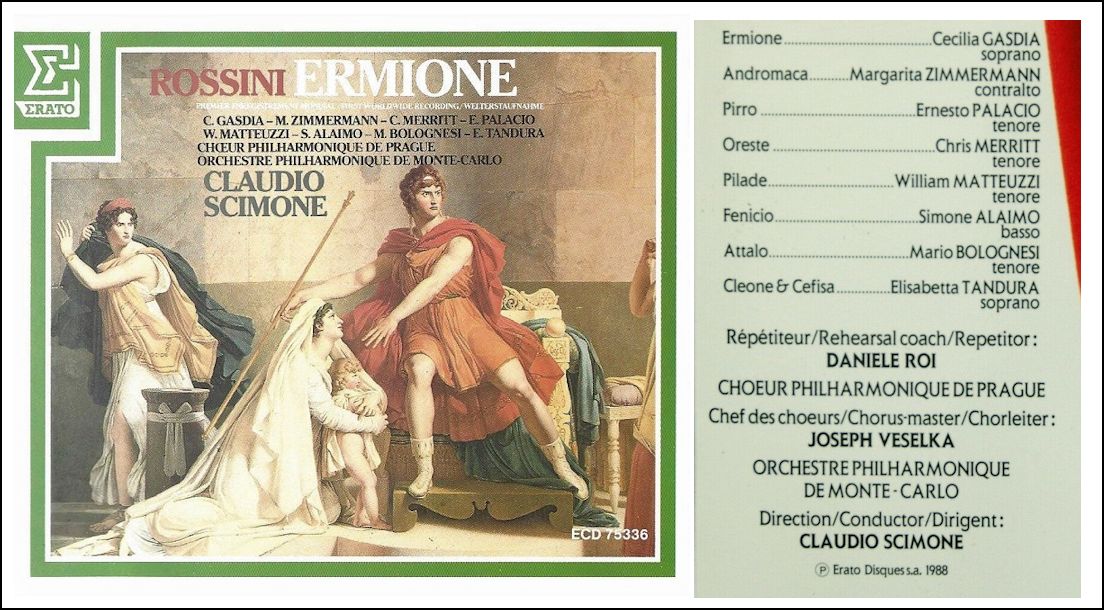

Ermione was first performed at the Teatro di San Carlo, Naples, on 27 March 1819. For reasons that are as yet unclear, the opera was withdrawn on 19 April after only seven performances, and was not seen again until over a hundred years after Rossini's death. One possible explanation for its failure might be Rossini's choice to renounce the use of secco recitative in favour of accompanied declamation and to connect each closed number to the next in a manner reminiscent of Gluck's French operas and of Spontini (the latter was also to have a huge influence on Weber's Euryanthe, four years later) Despite the opera's failure, Rossini seemed to be quite fond of this work and kept its manuscript, along with a few other from his Neapolitan years, until his death. The autograph score was then delivered by the widow, Olympe Pélissier, to Eugène Lecomte who entrusted it to the Bibliothèque Musée de l'Opéra de Paris. Eventually, a concert performance was given in Siena in August 1977. In old age, when asked if he would have liked Ermione to be translated and produced on French stages, the composer is reported to have replied, "It's my little Italian Guillaume Tell, and it will not see the light of day until after my death." The first modern staging was at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro on 22 August 1987, with Montserrat Caballé, Marilyn Horne, Chris Merritt and Rockwell Blake.

|

Merritt: Depends on where the audience is.

I’ve had no trouble here in America, I have to say, knock on

wood.

Merritt: Depends on where the audience is.

I’ve had no trouble here in America, I have to say, knock on

wood.

Merritt: If we choose to be left

out. It’s gearing itself towards those younger people.

If we, who are outside of that age group, decide to come along,

so much the better. I go along with it as many people do.

The people who are outside of that age group, are divided.

There are some people who enjoy it, and other people who don’t.

I grew up on Elvis, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Dave Clark Five,

and Sonny & Cher. I can’t completely shove it aside because

it was part of my life as well. I can’t discredit it and be a hypocrite

and say that type of music has never appealed to me. That would be

foolish, because when we were all ten years old, we turned on the radio,

and had our favorite tunes. There was no way round it. It

was just part of our culture as well. I don’t see how I could

have avoided it... not that I wanted to avoid it, because I listened

to everything. I also adore Country & Western music. Then

you have different degrees of elitists. You have different

degrees of people who are willing to accept things.

Merritt: If we choose to be left

out. It’s gearing itself towards those younger people.

If we, who are outside of that age group, decide to come along,

so much the better. I go along with it as many people do.

The people who are outside of that age group, are divided.

There are some people who enjoy it, and other people who don’t.

I grew up on Elvis, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Dave Clark Five,

and Sonny & Cher. I can’t completely shove it aside because

it was part of my life as well. I can’t discredit it and be a hypocrite

and say that type of music has never appealed to me. That would be

foolish, because when we were all ten years old, we turned on the radio,

and had our favorite tunes. There was no way round it. It

was just part of our culture as well. I don’t see how I could

have avoided it... not that I wanted to avoid it, because I listened

to everything. I also adore Country & Western music. Then

you have different degrees of elitists. You have different

degrees of people who are willing to accept things.

|

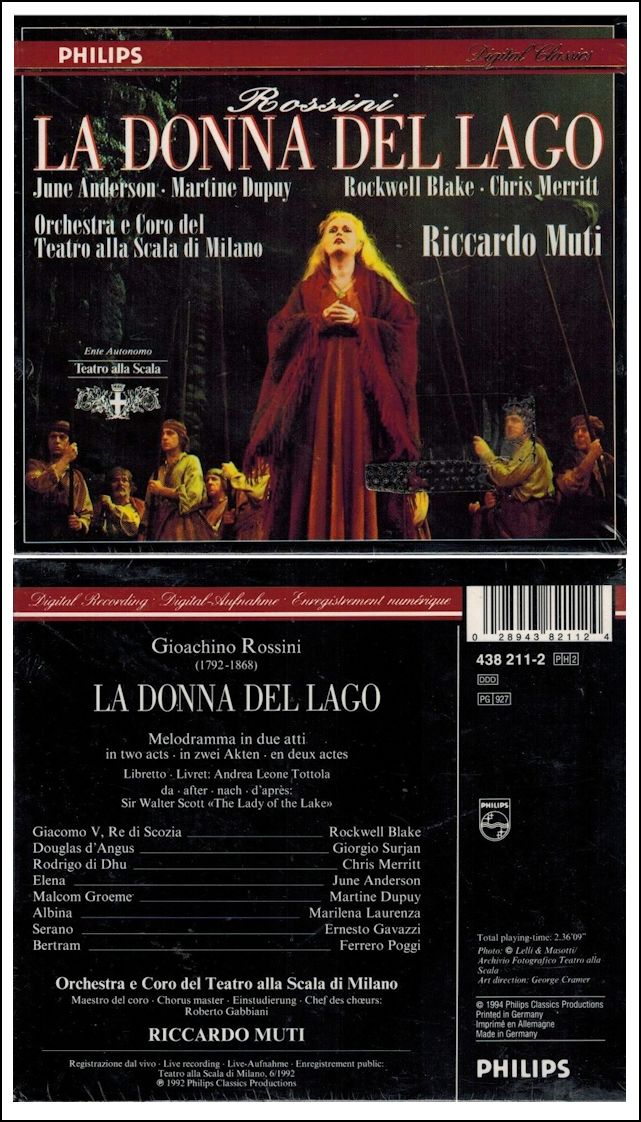

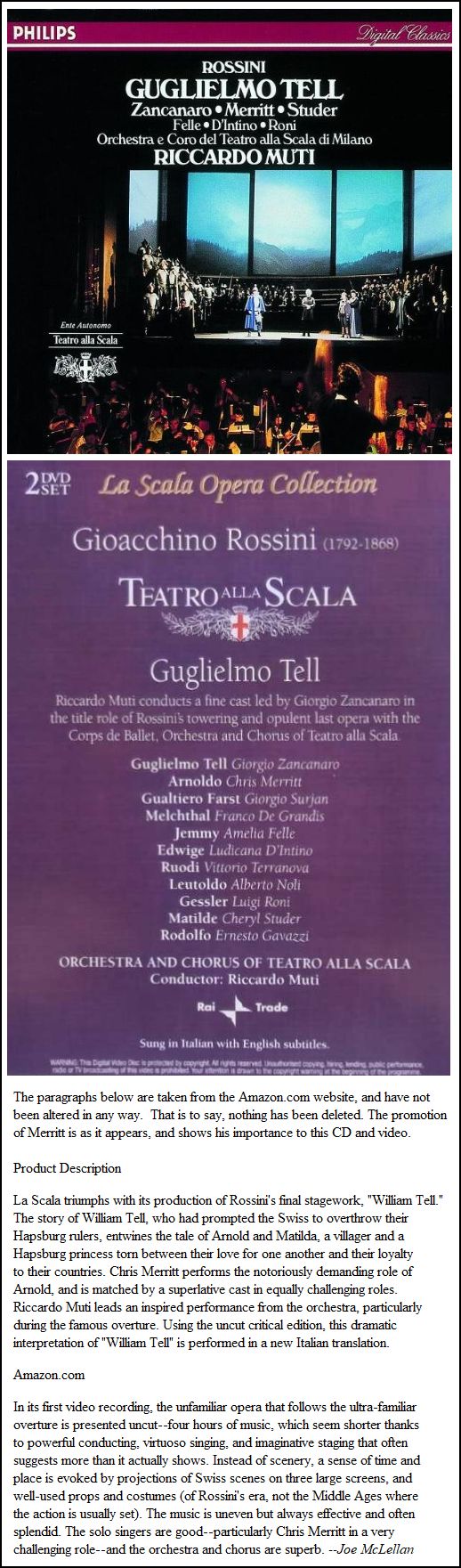

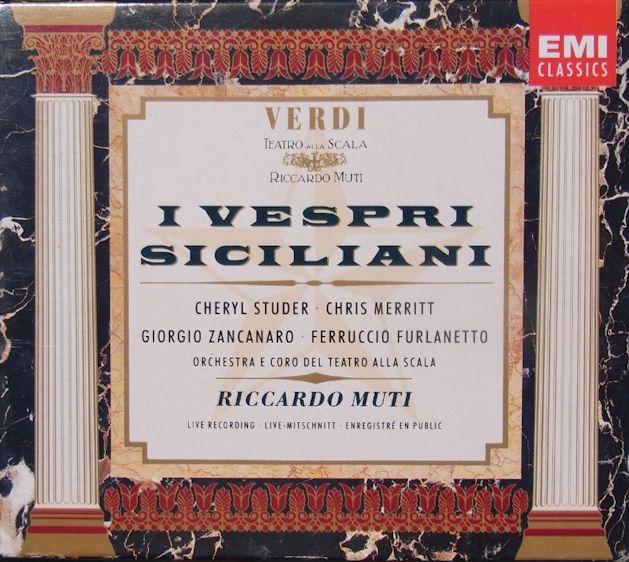

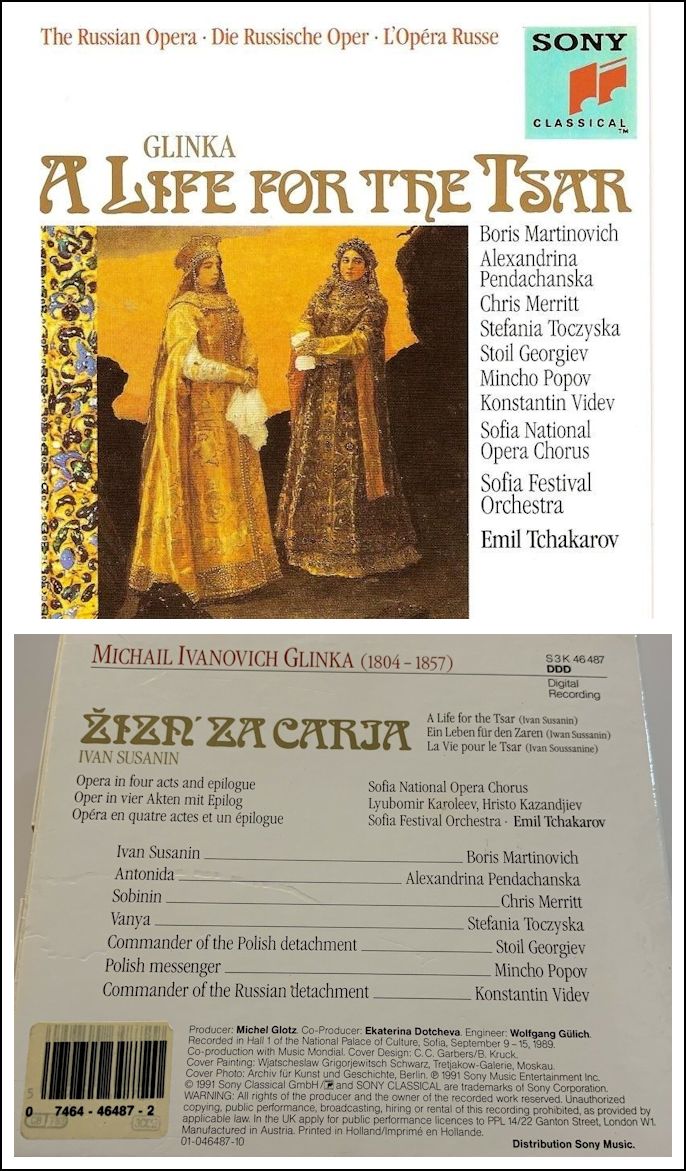

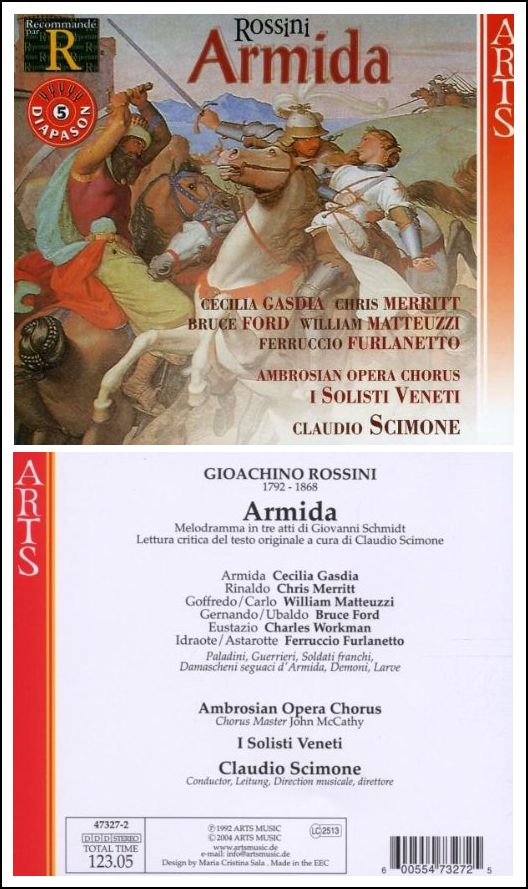

Chris Merritt (born September 27, 1952 in Oklahoma

City) is an American operatic tenor. Finally, Merritt began singing lessons in the preparatory department of Oklahoma City University at 15 years of age. His teacher was Florence Gillam Birdwell. By this time, he had already changed piano studies to Oklahoma City University (OCU) preparatory department with Dr. Robert Laughlin. It was also at OCU where he made his first operatic appearance in Douglas Moore's The Ballad of Baby Doe, at the age of 17, in a university production and singing alongside university-school-mate Leona Mitchell. At 18 and 19 years of age he performed and studied at Inspiration Point Fine Arts Colony, Arkansas, under direction of Dr. Isaac van Grove. At age 20 he was accepted at the Wolf Trap Farm Park for the Performing Arts in Virginia as fellowship artist where he studied and coached with John Moriarti, Benton Hess and Rhoda Levine. At age 21 he was accepted into the summer season "Apprentice Program for Singers" at The Santa Fe Opera. During his college career at Oklahoma City University from 1970 to 1978, Merritt's voice teachers were Inez Lunsford Silberg and Florence Gillam Birdwell. Later, he also received an Honorary Doctorate of Music from that institution. Merritt made his professional debut at The Santa Fe Opera in 1975, as Dr. Caius in Verdi's Falstaff, singing with Thomas Stewart in the title role in a production by Colin Graham and conducted by Edo de Waart. However, he also appeared in the Metropolitan Opera's National Council Regional Auditions National Finals Concert on March 28, 1976. In 1977, Merritt attended the American Institute of Musical Studies (AIMS) in Graz, Austria as a scholarship recipient. After hearing him at a presentation-concert, an agent sent him out on an audition tour through Austria, Switzerland and Germany. Merritt returned to the AIMS program in 1978 where he made his European debut in a concert broadcast live from Graz' Schloss Eggenberg on ORF Austrian National Radio, singing Janáček's song-cycle The Diary of One who Vanished and collaborating with pianist Norman Shettler. Merritt began a three-year engagement as ensemble member of the Landestheater Salzburg in the fall of 1978, while from 1981 to 1984 he sang as an ensemble member at the Staedtische Buehnen Augsburg in Germany. From 1978 to 1984, Merritt performed as guest artist in Kiel, Karlsruhe and Linz, as well as two seasons performing with "Fest In Hellbrunn" in Salzburg. Here he was heard singing in such operas as Gluck's La Danza (also in a studio recording for ORF Austrian National Recording), Haydn's Philemon und Baucis, Telemann's Der Geduldige Sokrates, Offenbach's Les Deux Aveugle and Richard Strauss' Des Esels Schatten, in a world premier of the posthumously-completed full-orchestration, which was recorded and televised for Austrian National Television. The performances with Fest in Hellbrunn were all conducted by Ernst Maerzendorfer. Performances of concert work during this period included Haydn's Der Schoepfung and Bach's St Matthew Passion (Evangelist and arias) in Denmark, Augsburg and with the Wiener Symphoniker in Vienna's Musikverein, Bruckner's Te Deum at Vienna's Konzerthaus, Beethoven's Ninth Symphony with the Hamburg Symphoniker, and Verdi's Messe da Requiem in Kiel. In Salzburg he was heard in Carl Orff's Carmina Burana, Mozart's Requiem, and Handel's Messiah. Additionally in Salzburg he was heard singing in Leopold Mozart's Lauretanische Litenei, Adlgasse's Te Deum and Michael Haydn's Requiem, all of which were recorded for the Schwann-Koch Label. Also during this time in Salzburg, Merritt sang in concert performances of the world premiere of Franz Richter Herf's Odysseus, together with Barbara Bonney. This was also recorded. Auditioning for Beverly Sills during her tour of Germany searching for US talent to bring back home won him the role of Arturo in I Puritani for his debut with the New York City Opera in 1981. That same year, Merritt met Marcel Prawy of the Vienna State Opera in Salzburg who arranged a house audition at the Viennese opera company. Merritt was offered the role of Leopold in Halevy's La Juive for his debut in concert performances alongside of José Carreras and Cesare Siepi. In 1983, Merritt made his debut at New York City's Carnegie Hall, singing Argirio in Rossini's Tancredi with Marilyn Horne and later in 1983, he made his Paris debut singing the role of Amenophis under Georges Prêtre at the Palais Garnier in Rossini's Moïse et Pharaon, the composer's Mose in Egitto rewritten in French. The production was directed by Luca Ronconi. Also that same year, Merritt made his UK debut in London with the London Philharmonic Orchestra singing Beethoven's Ninth Symphony at the Royal Festival Hall, conducted by Klaus Tennstedt. Merritt had five important debuts in 1985: he was heard at London's Royal Opera House, Covent Garden as Giacomo/Uberto in Rossini's La donna del lago, then at the Hamburg State Opera as Idreno in Rossini's Semiramide. His Italian debut was at Pesaro's Rossini Opera Festival, singing the role of Paolo Erisso in the composer's Maometto II in a production by Pier Luigi Pizzi. Shortly after, he performed the role of Conte Libenskof in Rossini's Il viaggio a Reims in a production at Milan's La Scala directed by Luca Roconi and conducted by Claudio Abbado. Finally, Merritt made his debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago as Percy in Donizetti's Anna Bolena, singing with Joan Sutherland in a production directed by Lotfi Mansouri with Richard Bonynge conducting. His Metropolitan Opera debut took place on November 30, 1990, when he sang again with Marilyn Horne and Samuel Ramey the role of Idreno in Rossini's Semiramide. That same season he sang there in the role of Arturo in I puritani along with Edita Gruberova and Paul Plishka, conducted by Richard Bonynge. Other principal roles in which he was featured at the Met included those in Rusalka, with Renée Fleming and Dolora Zajick in 1997, and in Káťa Kabanová with Karita Mattila and Magdelena Kozena in 2005, his last appearance in that house. Elsewhere, he sang again at Covent Garden as Idreno in Semiramide, Arnold in Guillaume Tell (in 1990 and in 1992), in Henze's Boulevard Solitude and in Katja Kabanova. At the San Francisco Opera he sang in Maometto II (debut in 1988), and also in the role of Arnold in Guillaume Tell in 1992 and 1997/98 season, in Rossini's Otello, in I vespri siciliani, and in St. Francis d'Assise and Doktor Faust. On August 6, 1993, he sang the title role in Sigurd at the sole performance of that rarely performed opera at the Festival Montpellier. In 1988 and in 1989 he appeared in the opening productions of La Scala's opera season, in Guillaume Tell and I Vespri Siciliani. Both were conducted by Riccardo Muti. He then returned as Rodrigo in La donna del lago, also conducted by Muti. At the Opéra de Paris, he returned to sing the title role of Benvenuto Cellini, appeared in two different seasons as Herod in Salome, as Le Lepreux in Olivier Messiaen's Saint François d'Assise, and as Eleazar in La Juive. In 2006, Merritt appeared in the American premiere production of Thomas Adès' The Tempest, marking his return to The Santa Fe Opera. |

© 1985 & 1993 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on November 9, 1985 and December 17, 1993. Portions of each were broadcast on WNIB in 1988 and 1997. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.