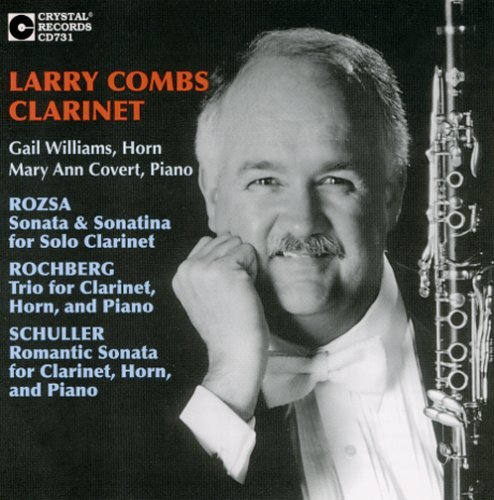

See my interviews with Miklós Rózsa, George Rochberg, and Gunther Schuller

|

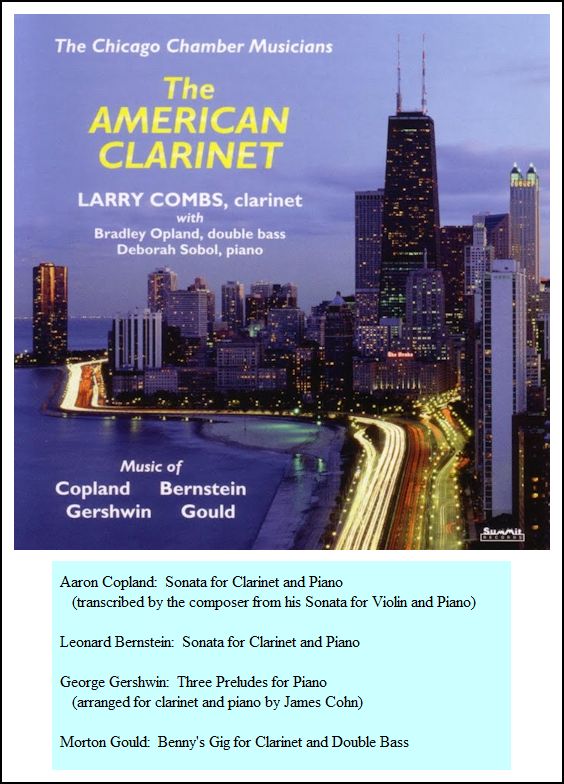

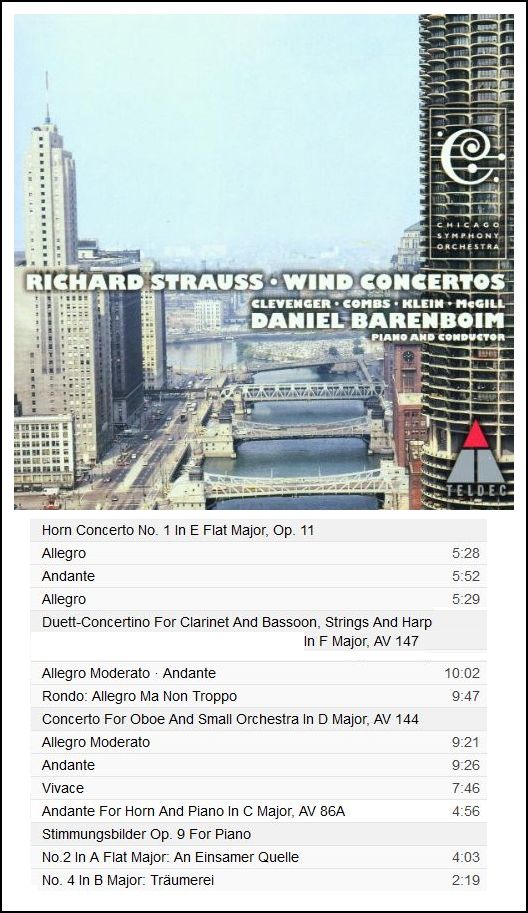

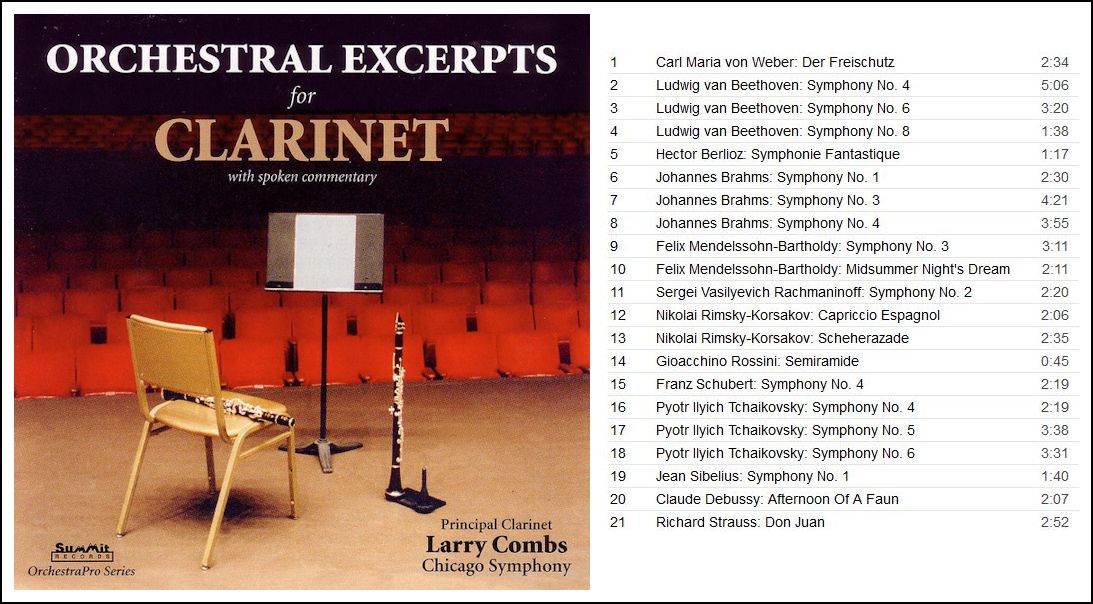

One of the world’s leading orchestral clarinetists, Larry Combs

(born December 31, 1939) has also been active in chamber music, and the Chicago

jazz scene. He began to play clarinet in Charleston West Virginia at the age of 10, and by the time he was 13 had a strong enough technique and reputation that he was regularly asked by the Charleston Symphony to play with them when an additional clarinet was needed. At age 16, he was the orchestra's principal clarinetist. While in high school his clarinet quintet entered the nationally televised Ted Mack Original Amateur Hour. The group placed second on the show, after a one-legged tap dancer. During the summer, he attended the National Music Camp at Interlochen,

MI, where he worked with professional musicians and the most talented

musicians from around the country in his age group. In 1957, he entered

the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY, where he was a pupil of

Stanley Hasty. He received a bachelor of music degree with distinction

as well as the Performer's Certificate in 1961. After graduating from Eastman, Combs joined the New Orleans Philharmonic as third clarinet/bass clarinet player. This job was interrupted when he was drafted into the military. After basic training he was sent to West Point and assigned to be a member of the United States Military Academy Band. This enabled him to travel to New York City for continuing studies with clarinetist Leon Russianoff. The New Orleans Philharmonic welcomed him back after his enlistment, this time as the orchestra’s principal clarinetist. In 1968, Combs became Principal of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra, and also played with the Santa Fe Opera. In 1974, he joined the clarinet section of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and in 1978, the orchestra’s music director, Sir Georg Solti, appointed him Principal Clarinet. He has appeared as soloist with the orchestra on many occasions, and can be heard playing on two decades' worth of the CSO records in virtually every important solo clarinet passage. He has won two Grammy Awards for Best Chamber Music Performance. He retired from the CSO following the 2007-2008 season to spend more time teaching clarinet students at DePaul University. He retired from DePaul in 2018. Combs is also a founding member of the Chicago Chamber Musicians. He has performed the Brahms Trio in A minor with Daniel Barenboim and cellist Yo-Yo Ma, and has appeared at the Ravinia Festival with its musical director, Christoph Eschenbach. Other appearances have been with the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center and the Smithsonian Chamber Players. Also a jazz player, his Combs-Novak Sextet was one of the headliners

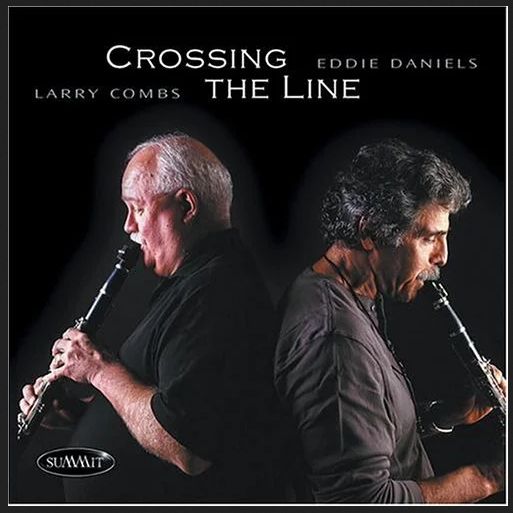

at the 1999 Chicago Jazz Festival and Combs recorded an album with jazz

clarinetist Eddie Daniels (Crossing the Line). Combs is a clinician

for the G. Leblanc Company, which makes the Opus II clarinets he helped

to design, and the Larry Combs models of clarinet mouthpieces. == Names which are links on this webpage refer

to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 2005 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in a rehearsal room backstage at Orchestra Hall in Chicago on February 26, 2005. Portions were broadcast on WNUR the following April, and again in 2015; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2005, 2007, and 2015. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.