|

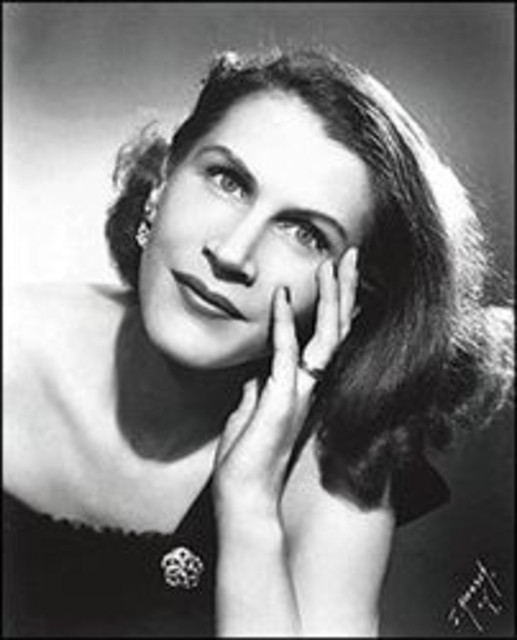

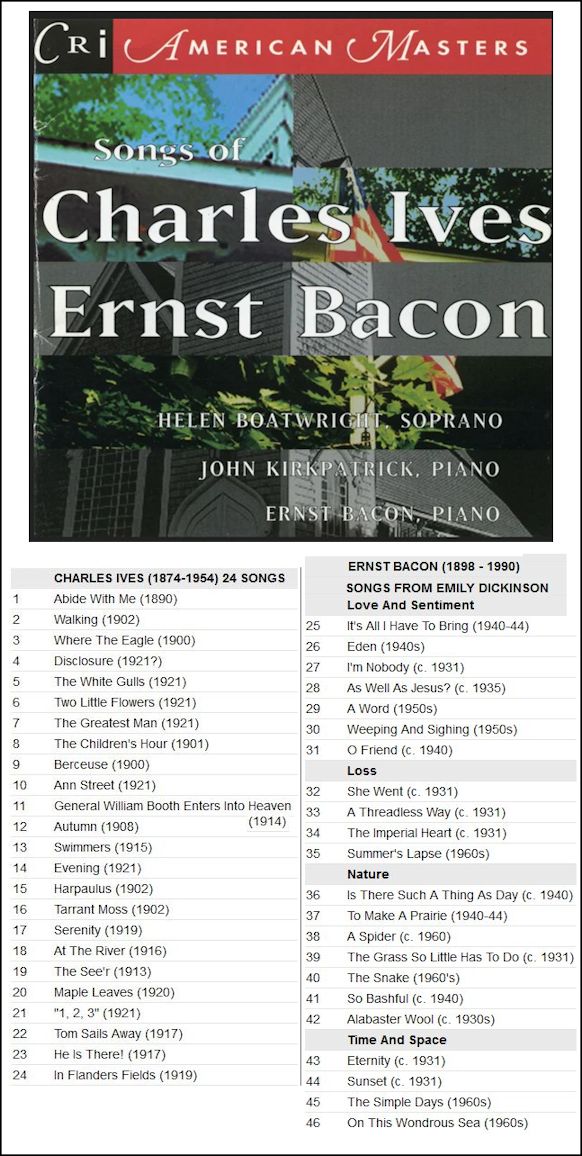

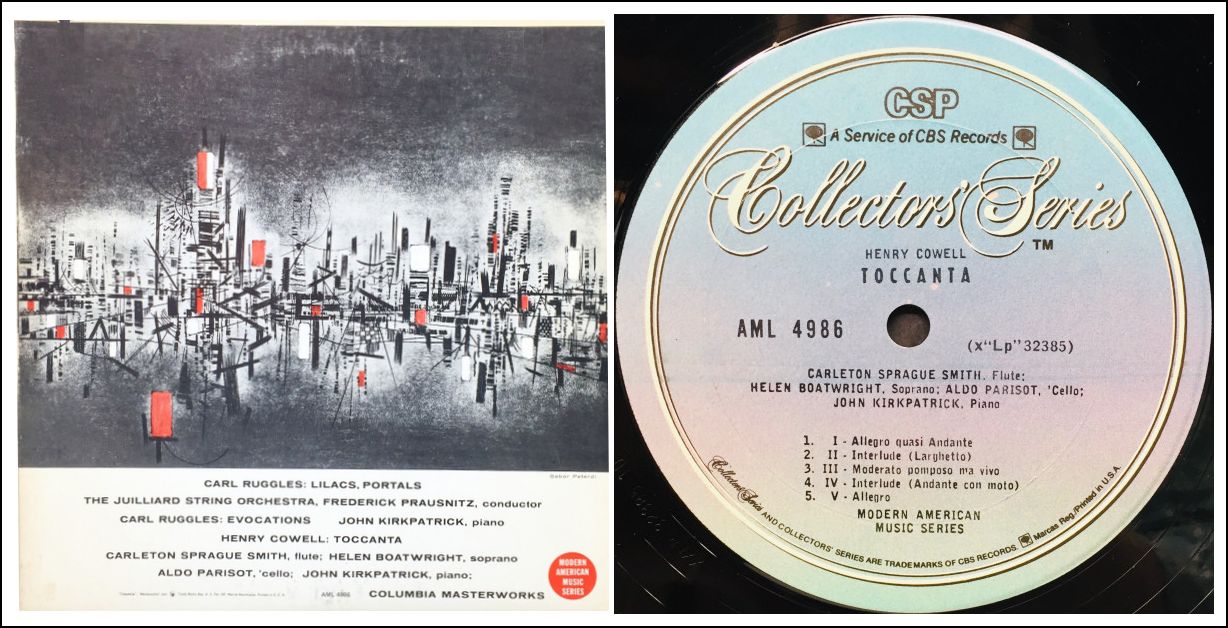

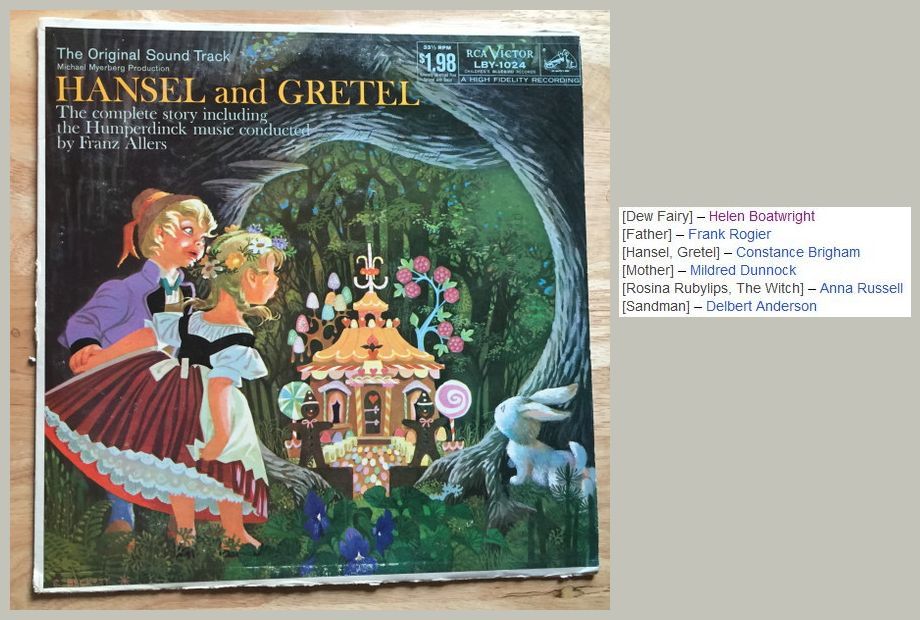

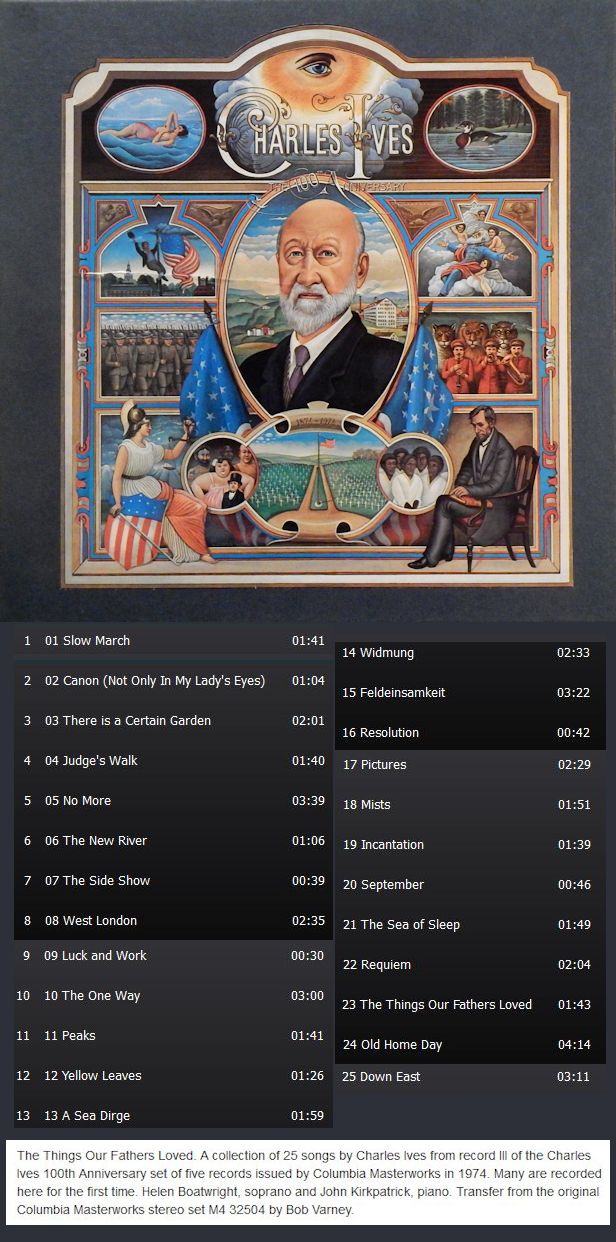

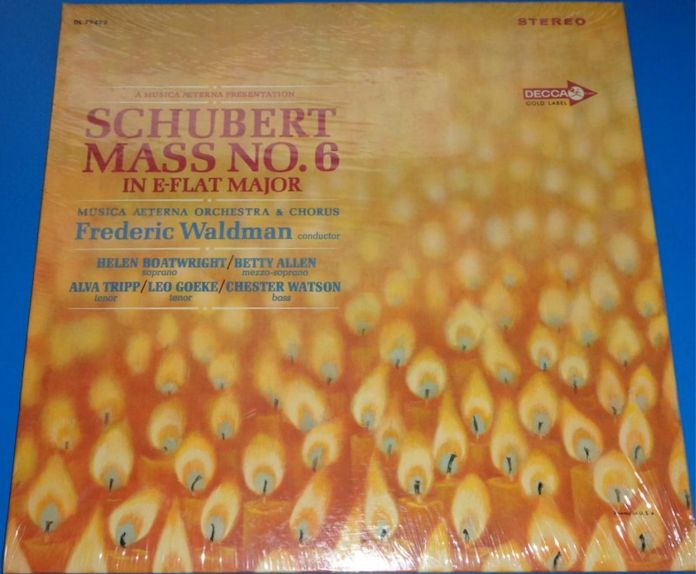

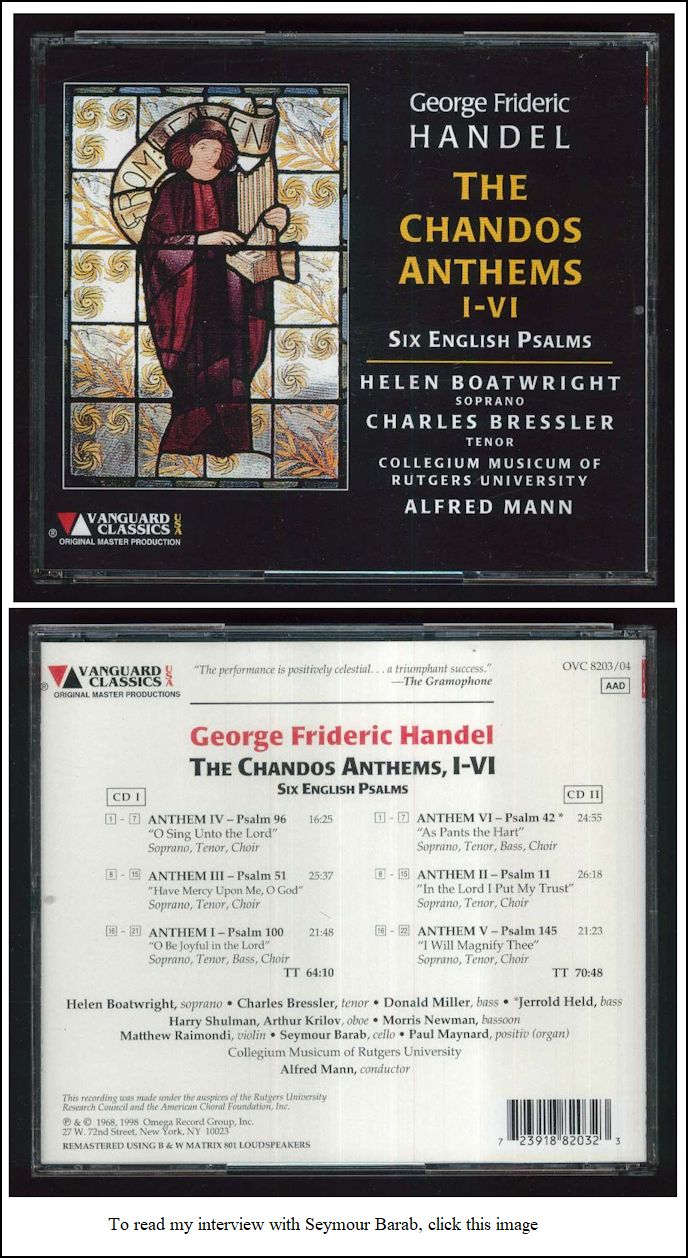

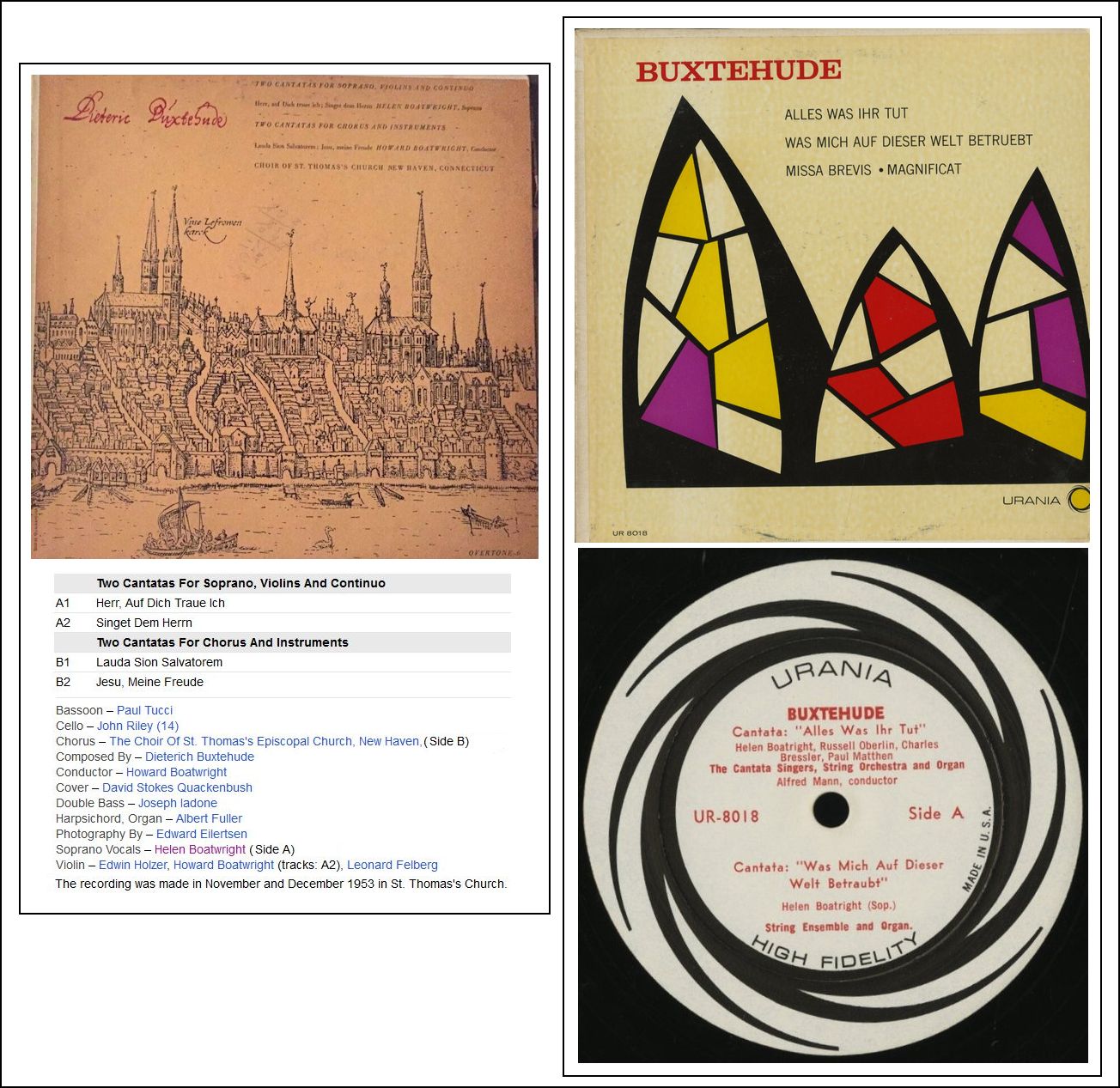

Helen Strassburger Boatwright (November 17, 1916 – December 1, 2010) was an American soprano who specialized in the performance of American song, recorded the first full-length album of songs by composer Charles Ives and had a career that spanned more than five decades. Born as Helena Johanna Strassburger in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, she was the youngest of six children in a large German American family. After high school, she studied with Anna Shram Irvin and earned bachelor's and master's degrees in music from Oberlin College. Her operatic debut was as Anna in a production of Otto Nicolai's The Merry Wives of Windsor at Tanglewood. During her career, she worked with many important figures in the world of music, including conductors Leopold Stokowski, Erich Leinsdorf, Seiji Ozawa and Zubin Mehta. She also performed with Leonard Bernstein at Tanglewood in the 1940s, sang opposite tenor Mario Lanza in his operatic stage debut, and performed for President John F. Kennedy in the East Room of the White House in 1963. In 1954, she became the first person to record a full-length album of Ives' songs, 24 Songs, with pianist John Kirkpatrick. She also studied with composer Normand Lockwood. Another particular favorite composer of hers was Hugo Wolf. She knew his songs intimately, and in her later years she nearly always included a set or even an entire half of a recital of his work. She met her future husband, violinist, composer and musicologist Howard Boatwright (1918-1999), in Los Angeles in 1941 when they were to perform in a National Federation of Music Clubs competition. They married two years later, on June 25, 1943, and had three children. They performed together throughout their married life in North America, Europe, and India. Many of her husband's compositions for voice were written for her. Other notable orchestral and choral groups she sang with were Paul Hindemith's Collegium Musicum, Alfred Mann's Cantata Singers, and Johannes Somary's Amor Artis Chorale. In 1964, her husband Howard became the dean of the Syracuse University School of Music and she joined him teaching there. In 1969 the Boatwrights established a university-sponsored summer program, L'École Hindemith in Vevey, Switzerland. They taught and performed there every summer until 1988. She was a professor of voice at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester from 1972 to 1979, and was a guest professor at Cornell University and the Peabody Conservatory of Music at Johns Hopkins University. She also gave master-classes at Glimmerglass Opera, University of Massachusetts Amherst, University of North Carolina and Washington University in St. Louis. In 2003, Syracuse University presented Boatwright with an honorary

doctor of music degree. Boatwright continued to study music and teach,

and in 2006, she celebrated her 90th birthday with a standing-room only

concert at St. David's Episcopal Church in DeWitt, New York. Her achievements

were honored during the 2011 Grammy Awards. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

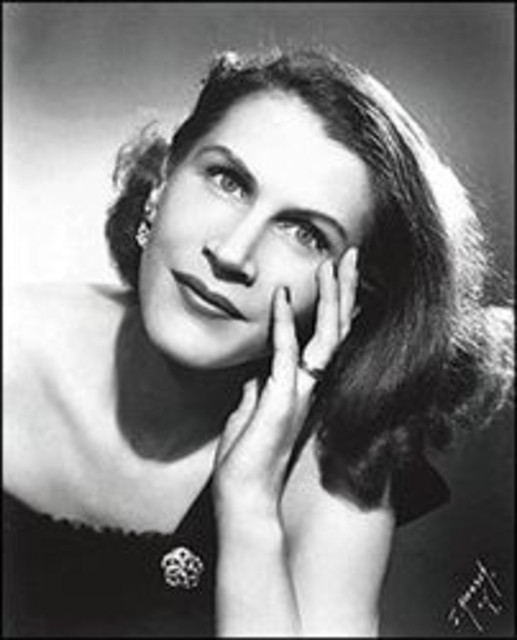

Julius Huehn (January 12, 1904 - June 8, 1971), professor of voice and chair of the voice department at the Eastman School of Music from 1952 to 1971. He studied at the Carnegie Institute and Juilliard. Mr. Huehn made his Metropolitan Opera debut in 1935, and performed regularly with them until enlisting in the United States Marine Corps in 1942, where he was a captain. After his military service, he returned to the Metropolitan Opera for the 1946-47 season. He was noted for his Wagner and Strauss roles, particularly for his portrayals of Orestes in Elektra and Jochaanan in Salome. Mr. Huehn also performed as a soloist with the Rochester Oratorio Society, the Worcester Festival, the Chautauqua Opera Company, the Philadelphia Opera, and the Chicago Grand Opera. Photo at right shows Huehn as Wotan in Das Rheingold and Die Walküre. == Text of this biography from the Eastman

School of Music website (with correction).

== Photo is from another source. * * * * * [Another singer mentioned by Boatwright much farther down on this webpage is Chase Baromeo.]

Chase Baromeo (August 19, 1892 - August 7, 1973), operatic bass-baritone, was born Chase Baromeo Sikes, son of Clarence Stevens and Medora (Rhodes) Sikes in Augusta, Georgia. He received B.A. (1917) and M.M. (1929) degrees from the University of Michigan. Before going to the University of Texas in 1938 to head the voice faculty in the music department of the new College of Fine Arts, he had a highly successful operatic career. He made his debut in 1923 at the Teatro Carcano in Milan, Italy. From 1923 to 1926 he was a member of La Scala in Milan, where he sang under Arturo Toscanini. Because of the Italians' difficulty in pronouncing his last name,

Sikes became known professionally as Chase Baromeo, and he used that

name for the rest of his life. He also sang at the Teatro Colón

in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1924, with the Chicago Civic Opera Company

from 1926 to 1931, and with the San Francisco Opera Company in 1935.

From 1935 to 1938 he was with the Metropolitan Opera Company in New York.

He also performed with many of the leading symphony orchestras in the

United States. He was married to Delphie Lindstrom on May 12, 1931; they

had three children, one of whom predeceased him. At the University of

Texas, Baromeo directed and performed in many university-staged operas.

He left the university in 1954 to join the University of Michigan faculty.

He died in Birmingham, Michigan. == Text of the biography is by Eldon Stephen

Branda from the Texas State Historical Association. |

|

Born into a family of musicians, Freeman grew up in Needham, Massachusetts and attended Milton Academy. His paternal grandfather played trumpet and cornet in Sousa's Band. His father was a double bass player in the Boston Symphony Orchestra, ultimately principal bass. In his youth he studied the oboe with Fernand Gillet in addition to studying the piano with Gregory Tucker. He went on concurrently to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree in music with highest honors from Harvard and a diploma in piano performance from the Longy School of Music in 1957. He also studied privately with Artur Balsam and Rudolf Serkin during the summers of 1955 and 1956. In 1957–58 he held one of Harvard's Sheldon Travelling Fellowships. He went on to pursue graduate studies at Princeton where he was awarded both an MFA and PhD in musicology. A Fulbright Scholarship enabled him to pursue further studies in Vienna in 1960–1962. He was also awarded a Martha Baird Rockefeller Foundation Award in 1962 and later an honorary doctorate from Hamilton College. In 1984 he was awarded Rochester, New York's Civic Medal, in connection with his work on downtown development. In 1963 Freeman joined the music faculty at Princeton, leaving in 1968 to join the music faculty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1972 he was named director of the Eastman School of Music (University of Rochester), a position he held for 24 years. From the fall of 1996 through the spring of 1999 he served as president of the New England Conservatory, then as dean of the College of Fine Arts at The University of Texas at Austin till 2006. In 2015 he retired from the Susan Menefee Ragan Regents Professorship of Fine Arts at UT Austin, where he taught courses on the history and future of music. A Steinway artist, Freeman performed in concerts and recitals throughout North America and Europe. He also made several recordings, mainly with colleagues from Eastman and the University of Texas. As a musicologist, his publications focused on 18th-century music history and on the history and future of musical education. His book, "The Crisis of Classical Music in America; Lessons from a Life in the Education of Musicians," was published in August 2014. He was awarded an honorary degree in April 2015 by the Eastman School of Music, which named the atrium of its Sibley Music Library in his honor. He was an emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Texas at Austin, as well as the senior educational liaison for Music in the Air (MITA), a revolutionary computer-mediated means of learning music, developed by UCLA's Robert Winter and Peter Bogdanoff and published by ArtsInteractive Inc., designed to develop broader audiences for music of all kinds while extending human attention spans. * * *

* *

The American soprano, Margaret Chalker (born 1958 in Waterloo,

NY), comes from a family of musicians. She first studied flute and

piano, originally intending to be a teacher, until her voice was

discovered. She obtained her Bachelor of Music Education degree from

Baldwin Wallace College, Ohio, (Studio of Sophie Ginn-Paster), and

studied six months in Italy. She also studied in New York with Marlena

Malas. She returned and taught intermediate and high school music for

a year in the Seneca Falls school district before receiving a Graduate

Teaching Assistantship to Syracuse University to study with Helen

Boatwright. She obtained her Master of Music degree in Music Performance

from Syracuse University in 1979.

The American soprano, Margaret Chalker (born 1958 in Waterloo,

NY), comes from a family of musicians. She first studied flute and

piano, originally intending to be a teacher, until her voice was

discovered. She obtained her Bachelor of Music Education degree from

Baldwin Wallace College, Ohio, (Studio of Sophie Ginn-Paster), and

studied six months in Italy. She also studied in New York with Marlena

Malas. She returned and taught intermediate and high school music for

a year in the Seneca Falls school district before receiving a Graduate

Teaching Assistantship to Syracuse University to study with Helen

Boatwright. She obtained her Master of Music degree in Music Performance

from Syracuse University in 1979.Her career that took her to many concert halls and opera houses in the USA, and in Europe beginning in 1985 at the Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf. In 1987 she made her debut at the Zürich Opera as Jemmy in a new production of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell. Since then she has appeared in more than twenty roles in over four hundred performances of works by Mozart, Puccini, Strauss, Wagner, Menotti and others. In 1991-1992 she sang Fiordiligi and Donna Anna, and in 1995 sang her first Donna Elvira. She has appeared as a guest artist at the State Theatres in Meiningen, Leipzig, Zürich, Dresden and Prague, with her debut in 1998 at the Hannover State Theatre. She has worked with distinguished conductors and in contemporary music has sung Luigi Dallapiccola’s Concerto per la notte di Natale dell’anno 1956 with Zürich Opera, and Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire with the Opera Nova Ensemble. She has also performed works by Henze and Ligeti. |

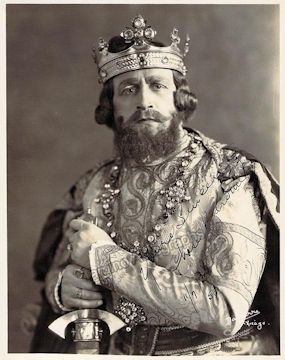

John Kirkpatrick (18 March 1905 – 8 November 1991) was an American classical pianist and music scholar, best known for championing the works of Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, Carl Ruggles, and Roy Harris. He also played and recorded music of Hunter Johnson, Robert Palmer, and Ross Lee Finney (among others). He gave the first complete public performance of Ives's Concord Sonata in 1939, which became a turning point in the composer's public recognition. Kirkpatrick played an important role in Ives scholarship, and he was leader in the Charles Ives Society. One important example is his role in the editing of Memos, which is a collection of Ives's autobiographical writings. At the time of his death Kirkpatrick was a professor emeritus at Yale University, where he had also been the curator of the Charles Ives archives. [The image below shows Kirkpatrick with the Yale Symphony in 1974]

|

|

* * * * * Donald Jay Grout (September 28, 1902 – March 9, 1987) was an American musicologist. He is best known as the author of A Short History of Opera, first published in 1947. The fourth edition was published by Columbia University Press in 2003. Grout was born in Rock Rapids, Iowa. He attended Syracuse University and graduated with a degree in philosophy in 1923. He took his Ph.D. at Harvard University in 1939. He taught at Harvard from 1936 to 1942, at the University of Texas from 1942 to 1945 and at Cornell University until 1970. Early in his career, Grout's main body of research was in opera. After 1960 he became more interested in philosophies of music history, due in large part to his publication of a general music history textbook, A History of Western Music. A ninth edition of the book was published in 2014. After Grout's death, the new editions were revised by Claude Palisca and J. Peter Burkholder. Grout also performed as a pianist and organist until the early 1950s. He served as editor of JAMS from 1948 to 1951, and was president of the American Musicological Society (1952–54, 1960–62) and the International Musicological Society (1961–64). A reassessment of Grout's historiography was published in 2011 in

the inaugural volume of Journal of Music History Pedagogy. |

|

Doty taught at the University of Illinois and at the University of Michigan. In May 1937 the Texas legislature passed a bill authorizing and funding the establishment of the University of Texas College of Fine Arts. The college had to be activated by the academic year 1938–39 or the funding would lapse. Doty was selected as dean after a nationwide search, and he moved to Austin in April 1938. As dean of the College of Fine Arts, chairman of the music department, and professor of music, Doty assembled a renowned faculty in art, drama, and music; wrote a catalog; purchased equipment; prepared a budget; and organized curricula. Doty taught courses in form and analysis, music literature, American music, aesthetics, philosophy, and fine arts administration. He also taught a number of distinguished organ students. Additionally, he taught classes in church music at the Episcopal Seminary of the Southwest in Austin. He served as organist at several Austin churches and performed solo organ recitals throughout the country, also frequently appearing as a lecturer or consultant. Doty composed several musical works, and in 1947 his text, The Analysis of Form in Music, was published by D. Appleton Crofts. From 1955 to 1958 Doty served as president of the National Association of Schools of Music; for six years, he was that organization’s representative to the American Council on Education. He served as president of the Texas Music Teachers Association from 1947 to 1949, and he served two terms as president of the Texas Association of Music Schools between 1949 and 1955. Other memberships included active roles in the Music Teachers National Association, the Music Educators National Conference, and the Texas Federation of Music Clubs. Doty was an honorary life member in the National Federation of Music Clubs. In addition he was a board member of the Texas Fine Arts Association and the Greater New York Chapter of the American National Theatre and Academy, and he was a charter member of the National Council of the Arts in Education. He organized the International Council of Fine Arts Deans in 1964 and served as its first chairman. He was also instrumental in founding the American Association of the Arts in Higher Education. He devoted his professional efforts to teaching, administration, and the establishment of accreditation standards and procedures, and he was an examiner/consultant for numerous schools throughout the country. Acknowledged for his consultant skills, Doty served as executive director of the Office of Cultural Affairs in New York City in 1964–65 during a leave of absence from the University of Texas. He was a member of numerous honorary societies including Phi Kappa Phi, Pi Kappa Lambda, Phi Delta Kappa, the Philosophical Society of Texas, and the Bohemians. He was also active in civic and cultural affairs in the city of Austin. Among his major accomplishments as dean of the College of Fine Arts and chairman of the music department was the construction of the university’s first music building in 1941–42. The structure was also the first air-conditioned building on campus. A drama building was dedicated in 1962, and the art building and Archer Huntington Museum in 1963–64. In 1965 Dr. Doty retired as chairman of the music department but

retained the titles of dean of the College of Fine Arts and professor

of music and continued to teach. He retired in 1972. Doty was married

to Elinor Wortley in 1934 and had three children. He was an Episcopalian.

E. William Doty died on June 16, 1994, and was entombed at Memorial

Hill Park Mausoleum in Austin. A scholarship fund had been established

in his name in 1962. In 1998 the E. William Doty Fine Arts Building on

the UT campus was named in his honor. == Biography by John H. Slate, from the Texas

State Historical Association website. |

|

Hege was born in Colorado and raised in Idaho to parents Carl and Anne, who he names as his role models. He attended the First Mennonite Church in Aberdeen, Idaho. He began piano lessons at the age of nine and realized at that age that music would be his ruling passion. He had majors in history and music at Bethel College, graduating in 1987. His senior seminar paper was about how the composer Dmitri Shostakovich worked under the repressive Stalin regime in Russia in the mid-20th century. He went on to obtain a master's degree from the University of Utah in orchestral conducting, where he founded the University Chamber Orchestra. He studied at the University of Southern California with Daniel Lewis and at the Aspen Music Festival with Paul Vermel. In 2004 Mr. Hege received an honorary doctorate in Humane Letters from Le Moyne College. He is active as a guest clinician and adjudicates various musical

competitions nationally. His positions have included

* * *

* *

Grant Cooper was born in Wellington, New Zealand, in 1953. His early childhood was filled with music, as his mother was a member of Opera Technique and, later, a soloist with the New Zealand Opera Company. His exposure to a wide range of music through his mother’s performances was formative in that it defined music for him primarily as a communicative language. Seeing his mother in roles as diverse as Suzuki in Madama Butterfly and Julie in Showboat helped to avoid any impression that music could be defined by genre. This desire to connect with the public through musical utterance has defined Grant’s professional musical life as a performer and composer.

In 1975, Grant toured Great Britain and China as a member of the National Youth Orchestra, during which time he performed as principal trumpet of the International Youth Orchestra under Claudio Abbado’s direction as part of the Proms in the Royal Albert Hall. Maestro Abbado invited Grant to join the orchestra of La Scala as solo trumpet. Instead, Grant accepted a fellowship from the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council for study with Bernard Adelstein and Gerard Schwarz in the United States, where he has lived since 1976. In the United States, Grant serves as Artistic Director and Conductor of the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra. For ten years, he was Resident Conductor of the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra, where he conducted close to 600 performances. Grant is especially passionate about creating works designed to introduce young audiences to the orchestra, including such works as Rumpelstiltzkin for narrator and orchestra, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Boyz in the Wood, for coloratura soprano and rap singer, and Song of the Wolf. His educational music is an eclectic blend of modern and established styles with interactive participation of the audience, a compositional style that reflects his belief that orchestral music is a living, vital, and relevant part of our society, able to be appreciated by all. In their March 2009 Pops concerts, the WVSO premiered Grant’s original scores for two Charlie Chaplin films: The Immigrant and Easy Street. His original concert work for soprano and orchestra entitled A Song of Longing, Though…, with poetry by Tom Beal, was premiered by the orchestra in April 2007 and was performed by the Chautauqua Symphony in 2010. Cooper was awarded the National Symphony Orchestra Chamber Music Commission following competitive adjudication as part of the 2010 American Residency program of the NSO. His new work, Octagons, was premiered at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC in May 2012 and was included in that season’s concerts by the Montclaire String Quartet. In 2013, Grant traveled to New Zealand on four occasions to conduct the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra in a national tour of a newly commissioned work by composer Gareth Farr for orchestra and theater ensemble, titled Sky Dancer. As a conductor, Grant's CD devoted to the premier recordings of the string music of New Zealand composer Douglas Lilburn has been enthusiastically received. Recently, he released Points in a Changing Circle, featuring himself as trumpet soloist in works by New Zealand composers and a CD featuring three of his own works recorded with the Cayuga Chamber Orchestra on a disc titled Boyz in the Wood. In September 2015 Grant announced that he would retire from the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra in 2017, to focus on family and composition. In 2012, Grant was honored by Governor Earl Ray Tomblin of West Virginia as the recipient of a Governor’s Award for Distinguished Service in the Arts. * * *

* *

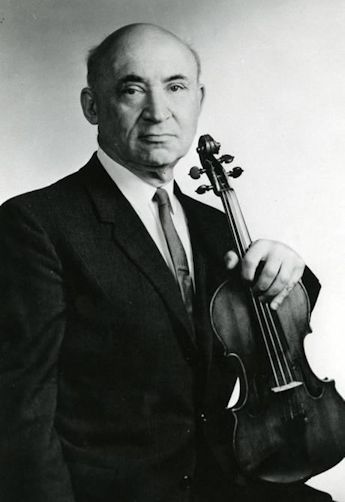

Louis Krasner (21 June [O.S. 8 June] 1903 – 4 May 1995) was a Russian Empire-born American classical violinist who premiered the violin concertos of Alban Berg and Arnold Schoenberg. Louis Krasner was born in Cherkassy, Kiev Governorate, Russian Empire (now part of Ukraine). He arrived in the United States at the age of 5, and graduated from the New England Conservatory of Music in 1922. He continued his studies with Lucien Capet in Paris, Otakar Ševčík in Písek, Czechoslovakia, and Carl Flesch in Berlin. His concert career began in Europe, where he championed the concertos of Joseph Achron and Alfredo Casella. In 1935 he commissioned Alban Berg's Violin Concerto, which he premiered on 19 April 1936 in Barcelona, with Hermann Scherchen conducting the Pablo Casals Orchestra. He also premiered Arnold Schoenberg's Violin Concerto in December 1940, with Leopold Stokowski leading the Philadelphia Orchestra. Among the American composers whose works he premiered were Roger Sessions, Henry Cowell, and Roy Harris. Krasner retired from solo performing to become concertmaster of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, a position he held from 1944 to 1949. From 1949 to 1972 he was professor of music at Syracuse University. In 1976 he joined the faculties of the New England Conservatory of Music and the Berkshire Music Center. He won the 1983 Sanford Medal from Yale University and the 1995 Commonwealth Award. |

BD: Ignoring the financial problems and the day-to-day

twitterings that always come up, what for you is the purpose of

music?

BD: Ignoring the financial problems and the day-to-day

twitterings that always come up, what for you is the purpose of

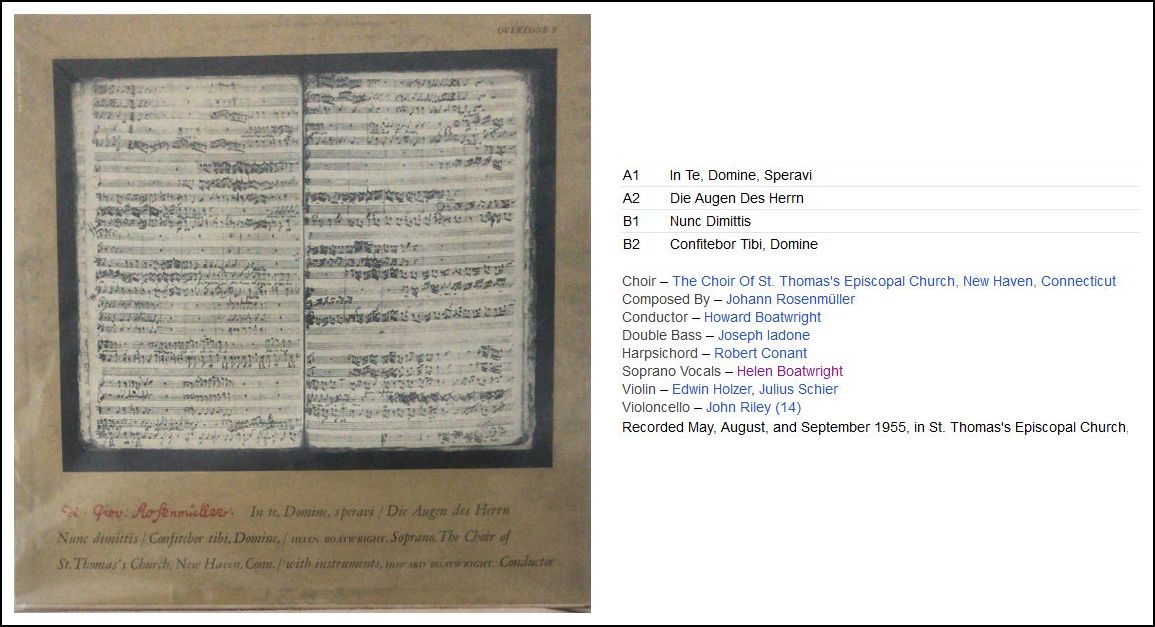

music?| Howard Boatwright (March 16,

1918 - February 20, 1999) was an American composer, violinist and musicologist.

He planned to become a violinist instead of a composer, but began writing music in 1941 as a way to court the soprano Helen Strassburger. They were married in 1943 and performed and recorded new music, standard vocal works, and early music together for many years. Helen Boatwright continued to have a distinguished career as a teacher and performer, sometimes in collaboration with her husband and sometimes independently. The couple had three children: a daughter Alice and two sons, Howard III and David Alexander. Howard became the music director at St. Thomas's Church, New Haven,

Connecticut, in 1949, a position he held until 1964. It was there that

he established a reputation as a pioneer in the performance of early

choral music. While in New Haven he also served as conductor of the

Yale University Orchestra from 1952 to 1960, and he was the concertmaster

of the New Haven Symphony Orchestra from 1950 until 1962. In 1964 he became the dean of the school of music at Syracuse University, and from 1971 he also served as a professor of music in composition and theory. At Syracuse, he transformed the music school, making it an important center for composition and the performance of new music by presenting festivals and establishing an electronic music studio. He also introduced non-Western music to the curriculum, and expanded its early music programs by acquiring collections of antique instruments. From 1969 to 1988, when he stopped teaching, he also directed a summer music program in Switzerland. He was a Fulbright lecturer in India during the year 1959–60 and

received a Fulbright grant to study in Romania, 1971–72. A pioneering

scholar of Charles Ives, he was elected to the board of directors of

the Charles Ives Society in 1975. He demonstrated an unusually wide breadth

of erudition as a scholar, publishing writings on music theory, ethnomusicology,

Charles Ives, and Paul Hindemith.

|

© 2003 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in the home of Helen Boatwright on August 22, 2003. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.