|

American soprano Carole Farley (born November 29, 1946) has become one of the most sought-after singers of her generation. She made her Metropolitan Opera debut in the title role of Lulu, a role she has repeated more than 100 times in four languages (German, English, French and Italian), including the first European production in Zurich. In recent seasons Farley performed the role of Emilia Marty in Janáček’s Makrapolous Case in Strasbourg, and her first Kaiserin in Strauss’ Die Frau ohne Schatten in Palermo. She made a triumphant return to the Met as Katerina Ismailova in its new production of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. She performed Strauss’Four Last Songs with the Czech State Philharmonic in Brno and recorded them for RCA/BMG; Berg's Seven Early Songs and the Mahler 4th in Spain and in Toulouse with the Orchestre du Capitol; Marie in Wozzeck for Toulouse Opera and Opera de Nice and La Voix Humaine in Finland, and Kurt Weill’s Seven Deadly Sins at the Helsinki Festival before embarking on a South American tour with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra singing Britten's Les Illuminations. To celebrate the Kurt Weill centennial she sang a series of concerts with the Bamberger Symphoniker and the BBC Symphony Orchestra and a recital in Miami in which she traced the steps of his musical journey from Berlin to Broadway to Hollywood. She also concertized with the orchestras of SWR of Baden-Baden and Freiburg, Lyon, BBC, Stockholm, Spokane, and the ABC Orchestras of Australia in evenings of Grieg, Richard and Johann Strauss, Berlioz, Henze, and Wagner. Other highlights included her

first performances of Britten’s War Requiem in San Sebastian,

Spain and with the Florida Symphony, and Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder

at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires, as well as Beethoven’s 9th and Ah,

Perfido! with the Hague Residenze Orchestra, and Mozart arias with

the Scottish Chamber Orchestra at the Bermuda Festival. In addition

to extensive concert tours in Lyon, Lille, Toulouse and Grenoble, she

sang Weill’s opera The Protagonist with the American Symphony

Orchestra at Avery Fisher Hall, and made a new Kurt Weill CD for ASV

with the Rheinische Philharmonie, including the world premiere recording

of Der Neue Orpheus. Other triumphs include Marcel Landowski’s

Montsegur at l’Opera de Marseille, Puccini’s Tosca

at Stockholm and the American premiere of Marc Neikrug’s Los

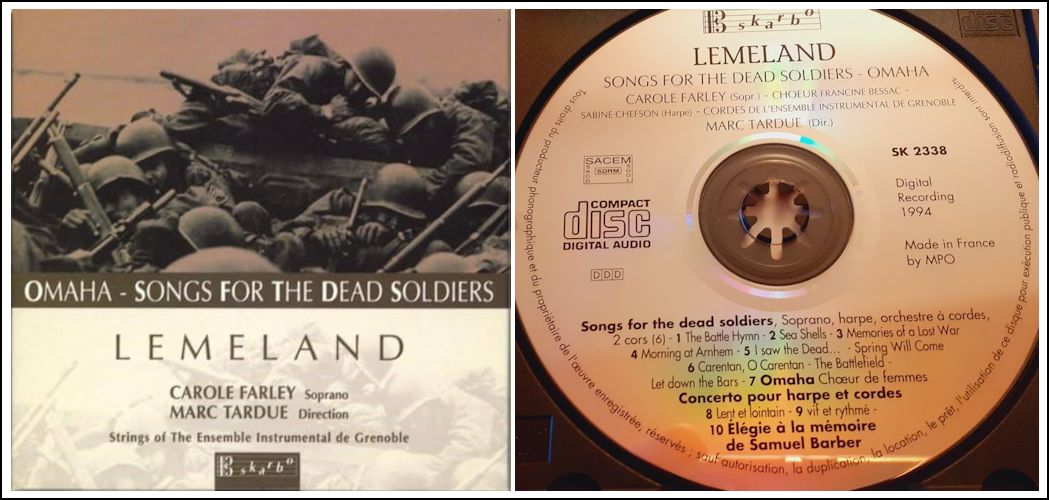

Alamos at the Aspen Festival. In 1998, she won the coveted Grand Prix

du Disque for her CD of Aubert Lemeland’s Omaha [shown below].

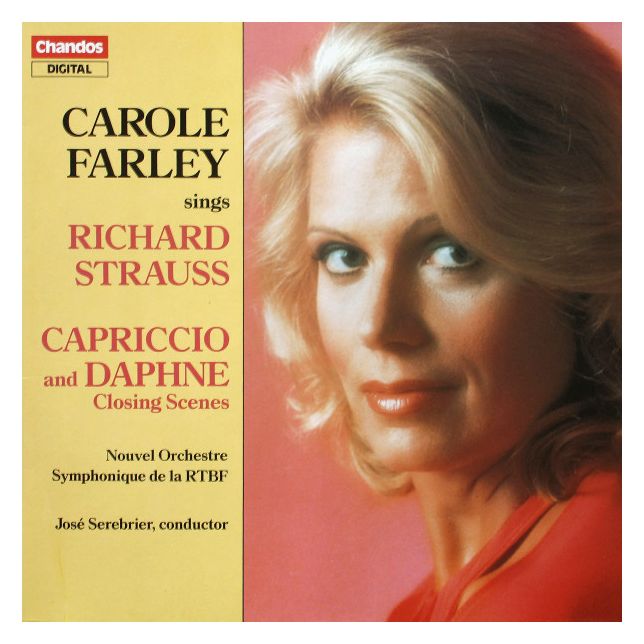

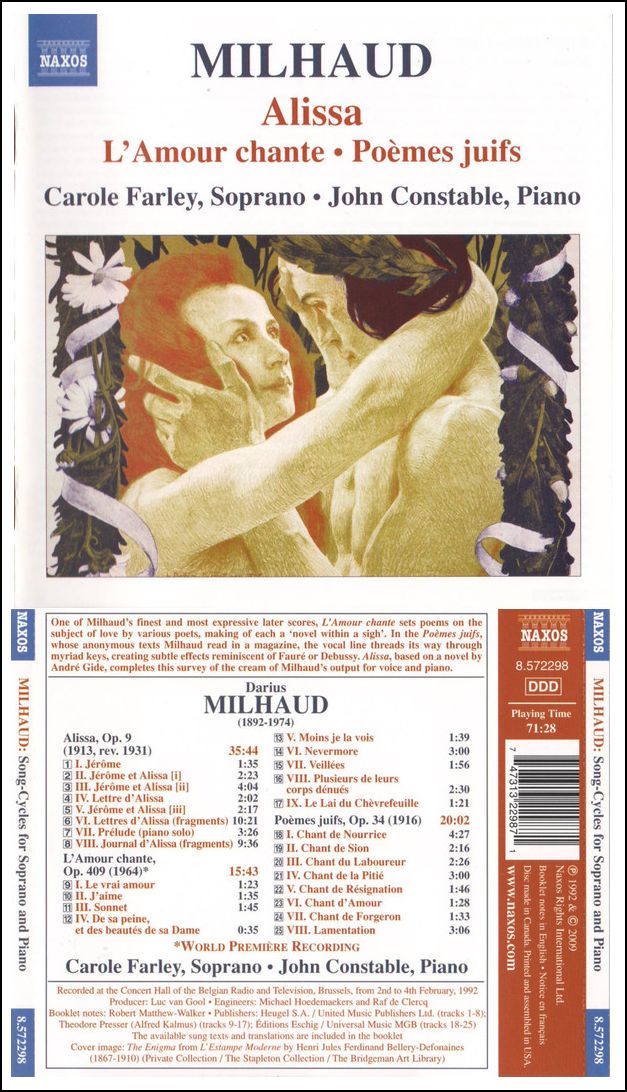

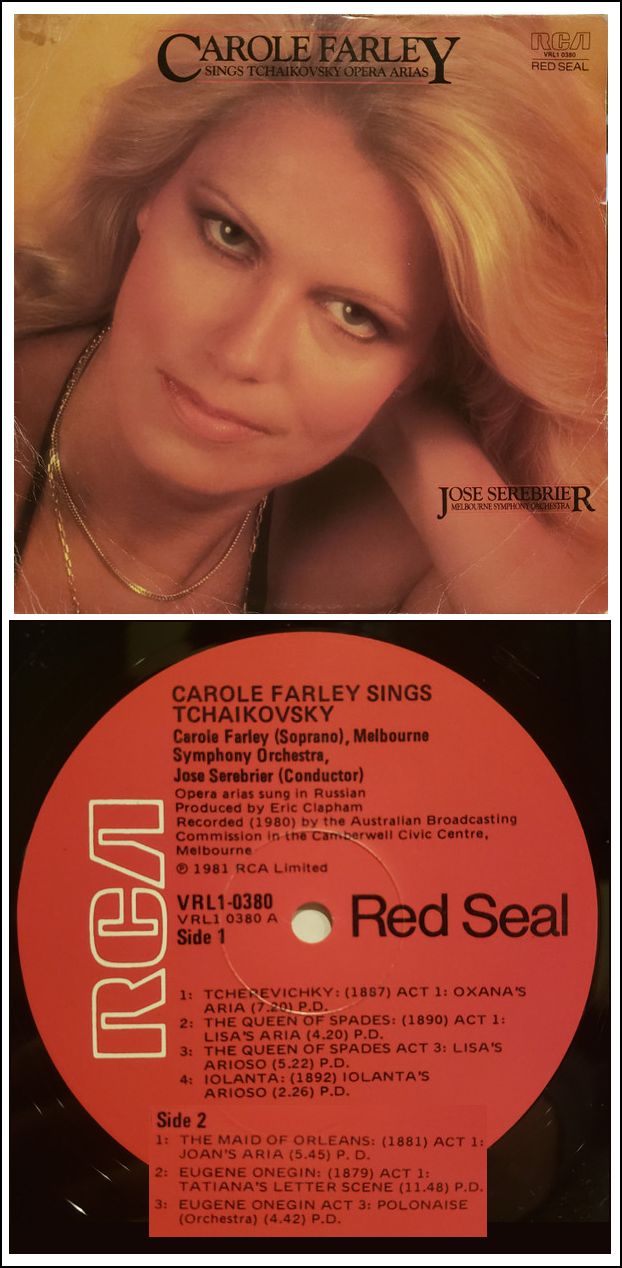

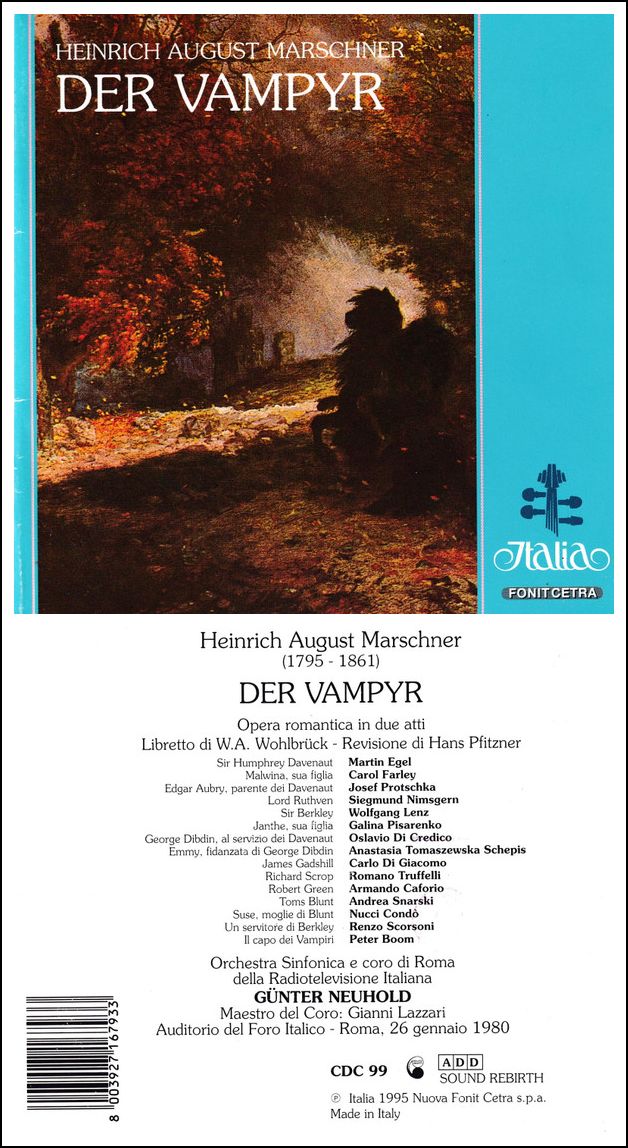

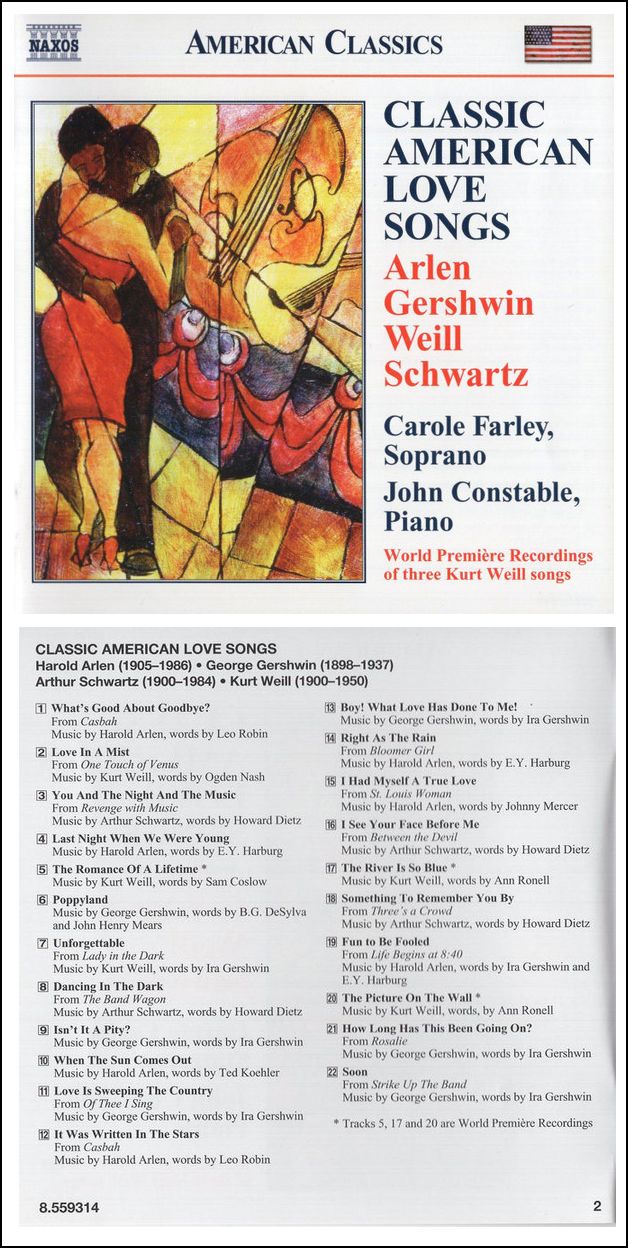

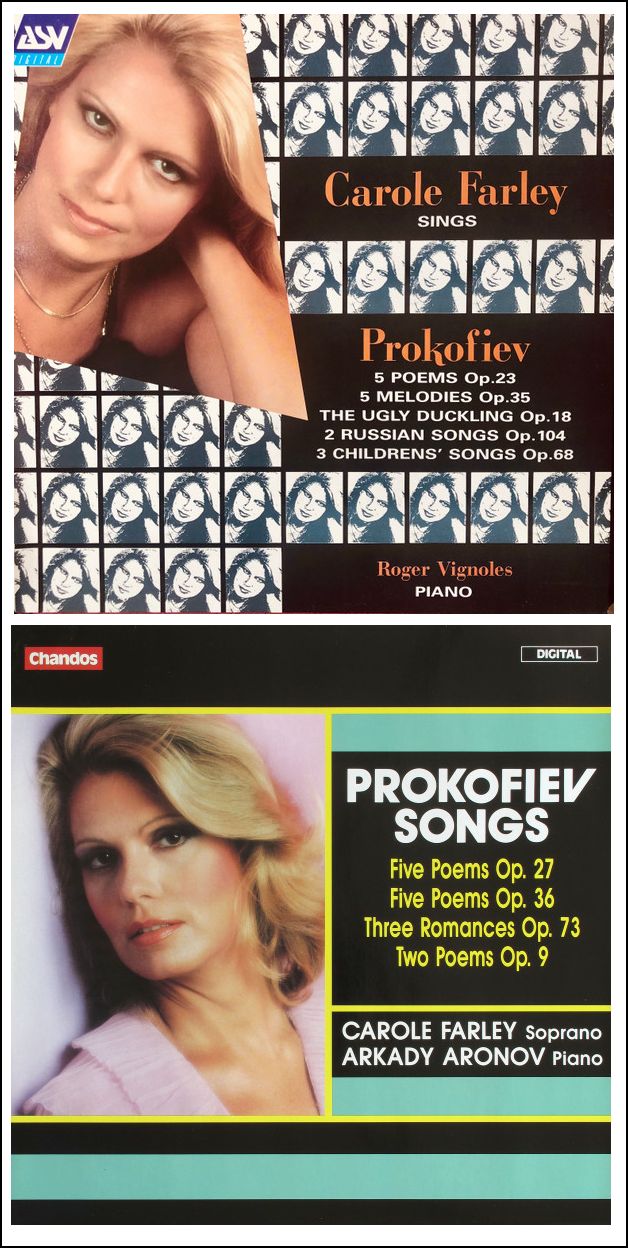

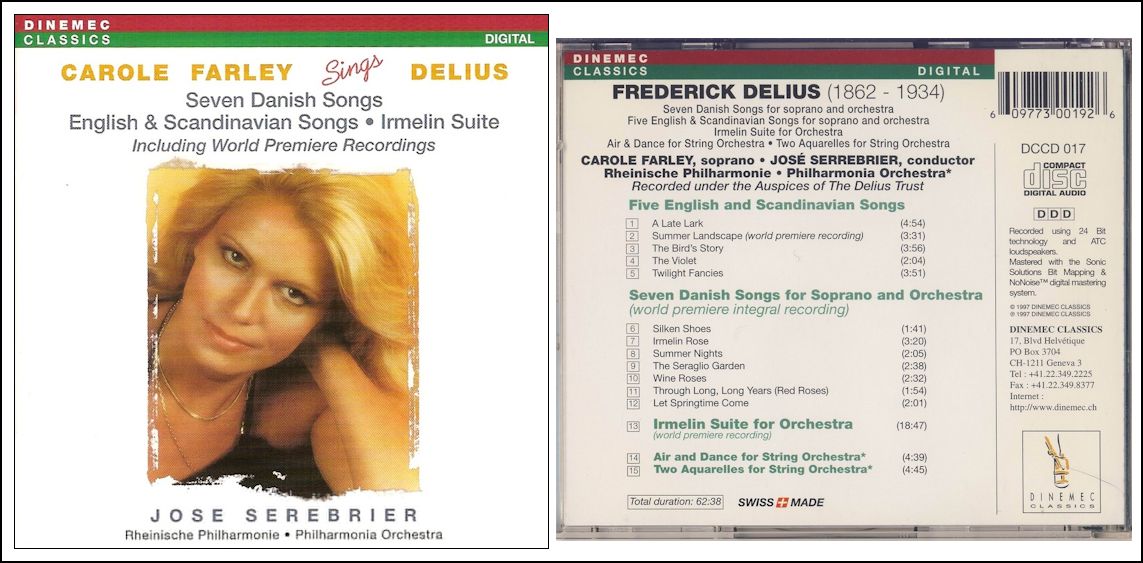

Farley has been a guest of the world's foremost theatres, including Lyric Opera of Chicago, Canadian Opera, Oper der Stadt Koln, New York City Opera, Welsh National, Teatro Colon, Zurich, Dusseldorf, Paris, Torino, Lyon, Brussels, Nice and Florence. Her varied repertoire includes Monteverdi's L’Incoronazione di Poppea, Massenet's Manon, Mozart's Idomeneo, Offenbach's Les Contes d’Hoffmann, and Johann Strauss' Die Fledermaus. Particular highlights in her career include over 50 performances of the acclaimed Paris production of The Merry Widow and the Lyubimov-staged Lulu for Torino which was awarded the Abbiati Prize for best production of an opera in Italy. She has claimed the role of Jenny in Mahagonny as her own following huge successes in Buenos Aires. Her performances of Poulenc's La Voix Humaine and Menotti's The Telephone have been filmed for Decca Laserdisc and VHS in co-production with the BBC. Her orchestral appearances have included most of the leading orchestras in the US such as the New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, Baltimore Symphony, and the National Symphony under conductors Zubin Mehta, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, Antal Dorati, Andre Kostelanetz and Sergiu Comissiona. Her European orchestra concerts range from the BBC Symphony, Royal Philharmonic, Concertgebouw, Orchestre National de France and the Radio Orchestras of Brussels, Paris, Torino, Cologne, Rome, the Hague, Helsinki and Barcelona with James Levine, Pierre Boulez, Jean Martinon, Gary Bertini, Nello Santi, Sir John Pritchard, Lorin Maazel, Edward Downes, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Andrew Davis, Lawrence Foster and Ferdinand Leitner. Farley can be heard on several notable recordings: the Beethoven Ninth Symphony with the Royal Philharmonic under Antal Dorati for Deutsche Grammophone, And Vienna Dances for CBS under Kostelanetz, Tchaikovsky Opera Arias for RCA, Guntram on BBC, Marschner's Der Vampyr on Foni-Cetra with the RAI Rome Orchestra, and, on Chandos Records La Voix Humaine, and Strauss' Final Scenes from Daphne and Capriccio. Her recording French Songs with Orchestra, the first in a series on ASV Records, received the Deutsche Schallplatten Critics Award. Performed with the RTBF Orchestra of Belgium and conducted by her husband, José Serebrier, it contains works of Chausson, Faure, Satie and Duparc. The second disc in the series contains world premiere recordings of songs by Debussy and Satie. Additional ASV discs include Prokofiev's The Ugly Duckling and albums of Prokofiev songs (one on Chandos, the other on ASV), recordings of Kurt Weill songs, Milhaud songs, Britten's Les Illuminations (with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra), Tchaikovsky Soprano Arias on IMP Masters with the Melbourne and Sicilian Symphony Orchestras. Her CD on RCA/BMG of Richard Strauss orchestral songs, including the Four Last Songs with the Czech State Philharmonic was released in 1997 accompanied by her ASV release of Kurt Weill music with the Rheinische Philharmonic. Her most recent recordings are

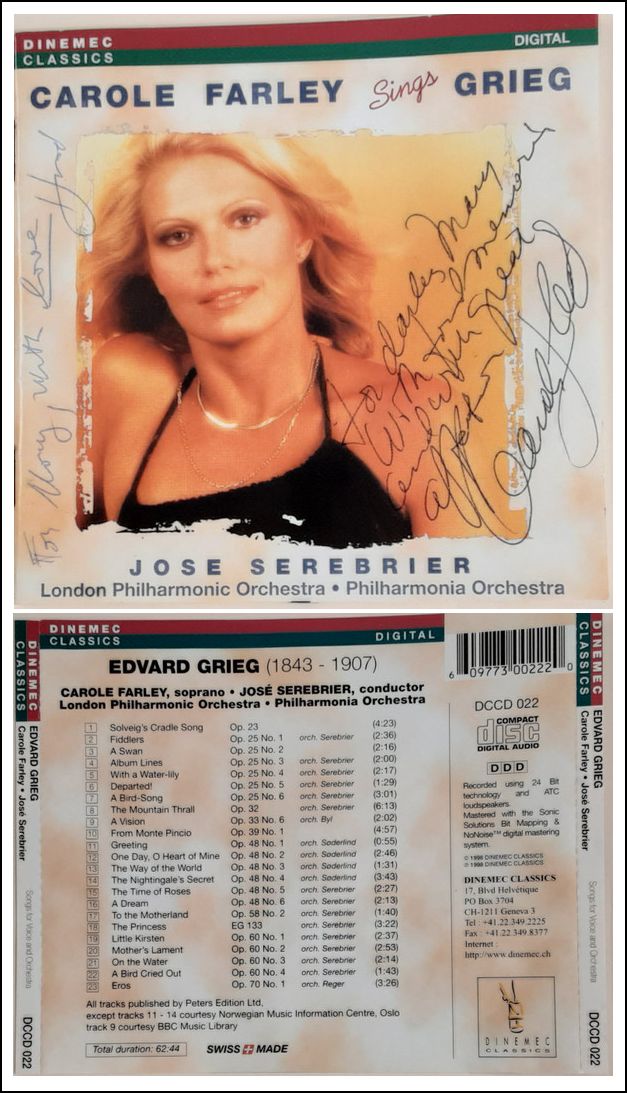

the highly acclaimed Carole Farley Sings Grieg, and Carole

Farley Sings Delius on Dinemec/Koch both with the London Philharmonic

and Philharmonia Orchestra and the 2001 release of Naxos’ Ned Rorem Songs

recorded in Nantucket with the composer accompanying

her at the piano. VAI International is currently re-releasing the French

recordings including the Milhaud songs and the French Songs with

Orchestra of Chausson, Debussy and Satie. Upcoming recording plans

include Naxos’ Songs of Charles Ives and The Songs

of Ernesto Lecuona for BIS. == Text of biography mostly from Lombardo

Associates website.

== Throughout this webpage, names which are links reefer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 16, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that year. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.