Composer Robert Kelly

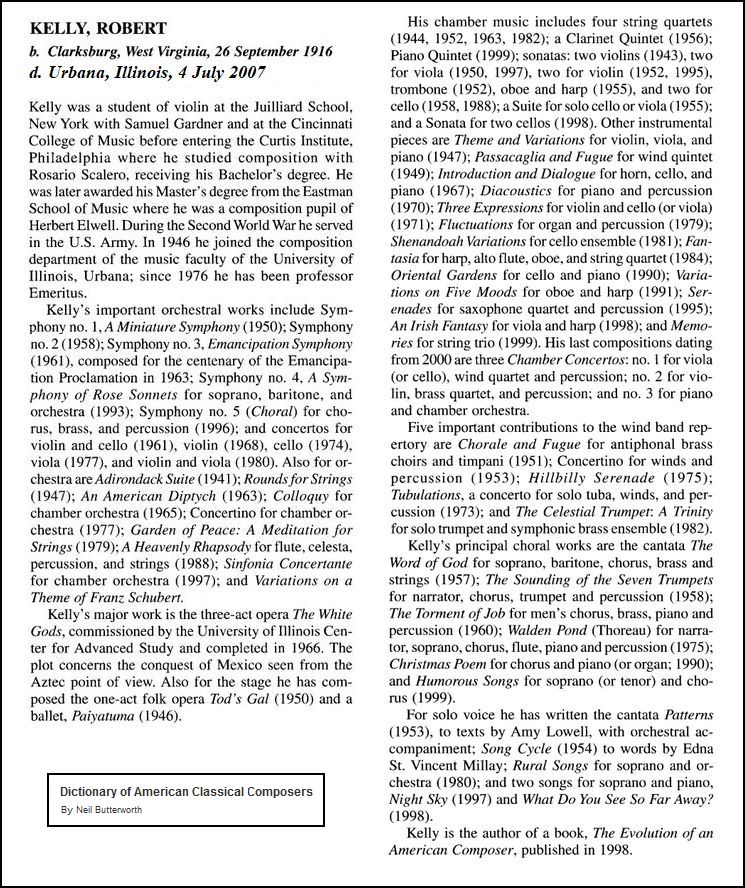

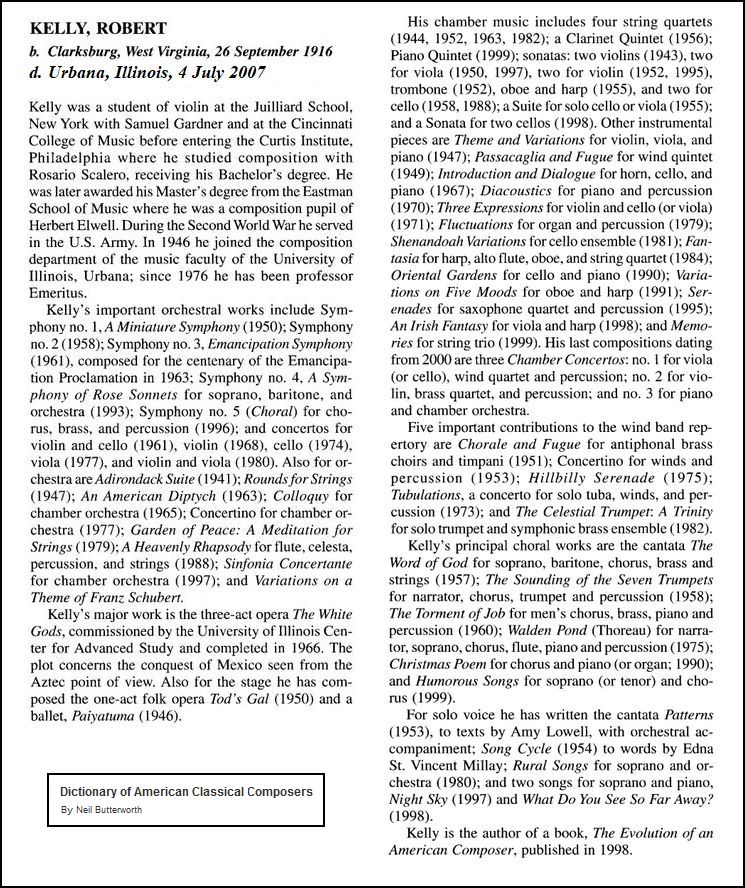

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

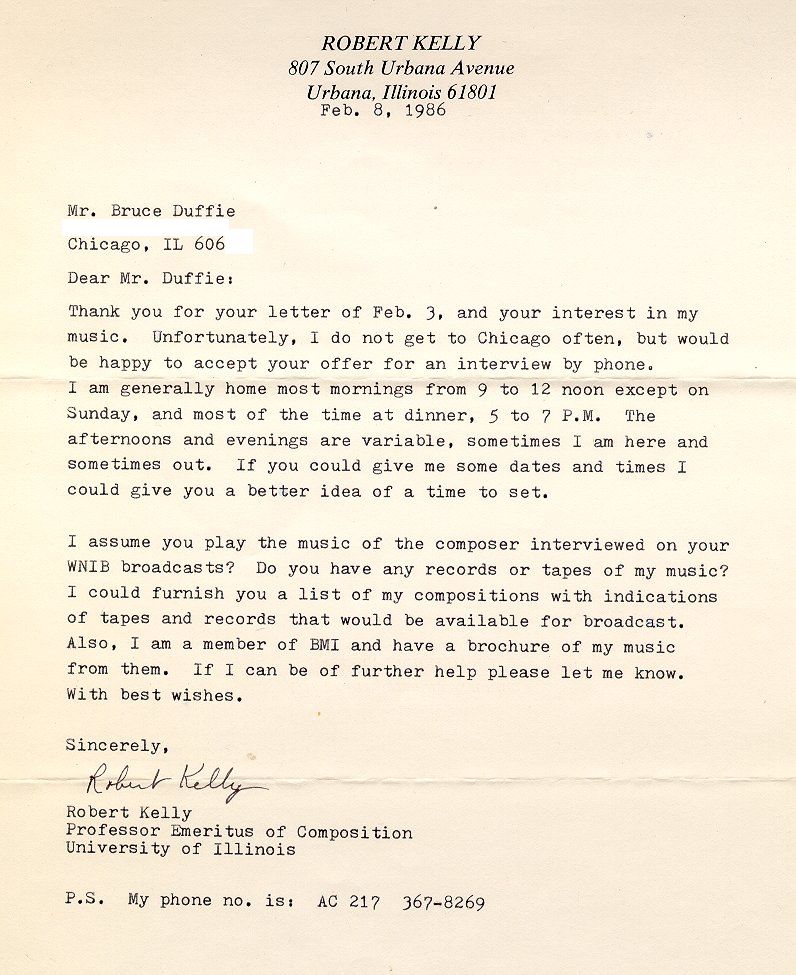

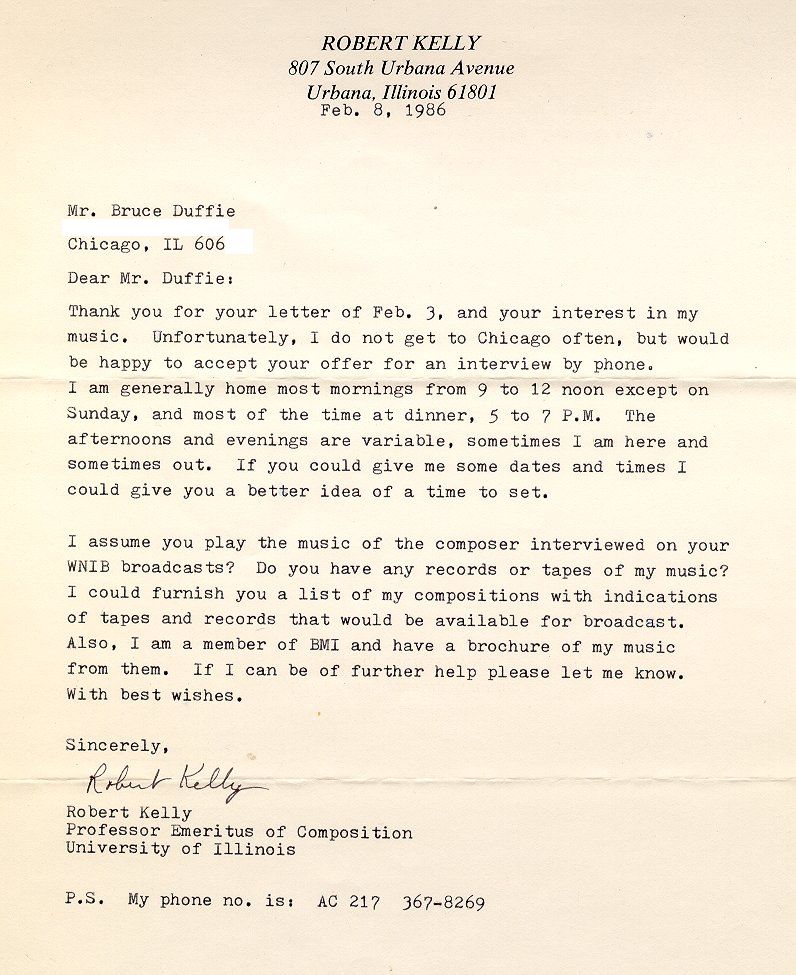

In March of 1986, composer Robert Kelly agreed to let me

call him on the phone for an interview. We spent about an hour talking

about musical subjects, and here is what transpired at that time . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You are now Professor Emeritus

from University of Illinois after teaching composition there for thirty

years?

Robert Kelly: Thirty years, yes.

BD: Let me start by asking you

how the teaching of young composers has changed over that time.

BD: Let me start by asking you

how the teaching of young composers has changed over that time.

Kelly: In thirty years it changed quite

a bit. The styles of composition were changing during the

’50s and ’60s, and

some of the ’70s. There was a lot of

experimentation of writing, especially with electronic music, and

computer music, which I didn’t go into at all. There were other

teachers who did that, and there were students who were interested in

it, but there are still some students who are interested in the fundamentals

and the traditional background. That’s the kind of student

I liked to have. You have to have a foundation, or where can

you go?

BD: One of the quotes I read from you

said that a composer expresses his time by drawing on the trends of

the past, and utilizing them, while adding to that with the experimental

trends of the present.

Kelly: Yes, and I still believe that.

That was written a long time ago, when I was much younger in my teaching,

but I still believe it. You have to have a good foundation.

BD: How much should a composer keep

up with all of the trends that are happening today?

Kelly: He should be aware of them, and

listen to them, and participate in them, or experiment with some

of the ideas. Any time you compose, you’re experimenting.

It doesn’t make any difference what style it is.

BD: [Somewhat surprised] Really???

You’re even experimenting with old styles?

Kelly: Yes, sure.

BD: Do all of the experiments succeed?

Kelly: Oh, no! [Much laughter]

Some of them don’t even get past the paper, and to performance.

The composer has to decide when this is not good. I’m a disciplinarian.

As a teacher, and as a composer myself, I believe in choosing the best

that you can put out, and learn to discriminate what are good ideas and

what are bad. But that, of course, is only one person’s opinion.

When it gets out in the public, then there are the critics and others

with their own opinions.

BD: How do you decide what you feel

is good and what you feel is bad? What criteria do you use

in making those choices?

Kelly: I still like to have some kind

of lyric quality to my music, for one thing, and I like to have rhythmic

drive. A lot of those are things composers in the past thirty

years have thrown away. They feel it’s old hat. You shouldn’t

have rhythmic drive, and you shouldn’t write things that have key centers

or tone centers. You shouldn’t write anything that’s already been

written before. However, I don’t see how you can avoid this.

A long time ago, Edison said there’s no such thing as a new melody.

I don’t know how to take that, but there’s not a lot of things that are

new. The new things come from your own personality. When you

put your personality and your thoughts into it, it can be a new in a way,

but it will have a lot of resemblance of other composers, or other poets,

or writers.

BD: Should it be old ideas used in new

directions?

Kelly: Yes, yes.

BD: Do you feel that you are part of

a line of composers, that your music fits into a line of established

composers?

Kelly: That’s hard for me to say.

I don’t feel I go along with the trends of my colleagues. There

were about six or seven trends going at the same time when I was teaching

composition, and I don’t feel I follow any of them.

BD: Do you feel that you follow the

famous forebears in music?

Kelly: Oh, yes. I’m influenced

a lot by other composers. In the early days, it was Stravinsky

and Bartók, but not so much of Webern and the Schoenberg School.

That never appealed to me too much.

BD: You say your music always has tonal

centers and lyricism. Is your music, perhaps, easier for the

public to grasp than something that is more complex?

Kelly: I think so, yes. It depends

on which public is listening. It might be a public that doesn’t

like any kind of classical music, and they don’t even understand it.

Or, it might be a public that enjoys listening to ideas, but not

as far as going into avant-garde or electronic experimental music.

Those are on the other side of the spectrum.

BD: Do you write for any specific public,

or do you write for yourself?

Kelly: It’s a combination. I write

for myself, naturally. Most composers do. But I also write

for other people to enjoy, as well as playing it, and listening to it.

My music is not easy to understand on first hearing. It takes

a long time for some people, but I want people to listen to the music.

I don’t see any use in writing music that you’d feel nobody cares about.

I’m going to write this as I want. I think Charles Ives did that

in a lot of cases... he wrote just what he wanted to, and he didn’t care

whether anybody heard it.

BD: So you care very much about people

listening to it?

Kelly: Oh, yes. It’s a waste of

time if you don’t communicate. Music is a communication vehicle,

and if you don’t communicate to another person, what good are you?

If I had talked to you today in a foreign language, you wouldn’t even

understand what I’m talking about. So, what good would the conversation

be?

BD: It would be a waste of time.

Kelly: Yes!

BD: What do you expect from the public

that comes to hear your music?

Kelly: I hope they will come to hear it

in the first place, and if they don’t like it, why is that? They

can say something to me if they want to, or not say anything.

I’ve had some people say to me, “I don’t like what

you’re writing.” I asked why, and they responded,

“You’re just like all the rest of these composers

around here. I can’t understand it.”

When they say that, I understand right away that they don’t understand

anything that’s new. They feel I’ve got to write like Tchaikovsky

and Brahms, and this I refuse to do. [Both laugh] Brahms

is already done. I studied with a teacher who was fifty years

my senior at the Curtis Institute of Music, and I guess you could call

him a pupil of a pupil of Brahms. His music sounded like Brahms,

and he wanted all his students to write music sounding like Brahms.

Well, I did it up to a point, but after that I didn’t make it like that

anymore.

BD: You went off into your own style?

BD: You went off into your own style?

Kelly: Yes, and the same thing was true

of Hindemith’s teaching. I didn’t study with Hindemith, but

I knew him, and I knew his students. He expected you to write

like Hindemith. That’s one of the things I refused to do when

I was a teacher — to have my students

to write like me. I didn’t want them to do that. I want them

to demand the techniques, the discipline of composing and, after a couple

of years, they go off on their own. If I didn’t like what they wrote,

or I couldn’t feel I was qualified to criticize it, they could study with

someone else, because we had a variety of teachers at the University

of Illinois.

BD: This is one of my favorite questions

to ask composers, who especially those who are teachers and professors

of composition. Is musical composition something that

can be taught, or must it be something that is innate to the young

composer?

Kelly: I don’t know whether you can really

teach composition. You can teach some students the techniques,

the basics and ideas on how to organize, or you might even let them

know some of your inner secrets of how you put a piece together.

But actually, a person learns to compose by himself, really. I

never thought that the teachers I studied with actually helped me to be

a composer. They helped me to learn the techniques.

BD: They helped you to be a musical

craftsman?

Kelly: Yes.

BD: In musical composition, how much

is technique, or craft, and how much is inspiration?

Kelly: It’s hard to say. Usually

you come out with fifty-fifty, but I never thought much about it, one

way or the other. I know it’s been a while since I studied composition,

so I was always shaping it a bit to write what I want to write, and

the teacher would say I was sounding like this other person.

I was accused of sounding like Roy Harris, and it didn’t sound like

Roy Harris or anything else. If I sounded like anything, it was

a little bit impressionistic, and somewhat a mixture of Impressionism

and Romanticism. I would say that my music today is still that,

but in a different way, in a more mature way.

BD: You’ve been composing for fifty

years or so. How has your music changed over the half-century?

Kelly: A lot of it has to do with organization,

and how I structure it. I learned a lot of things on my own

since I’ve been teaching. If you want to talk about experiments,

I’ve experimentally talked on music in my own way, and even that has

changed in the last thirty years, as to the approach to it. Listen

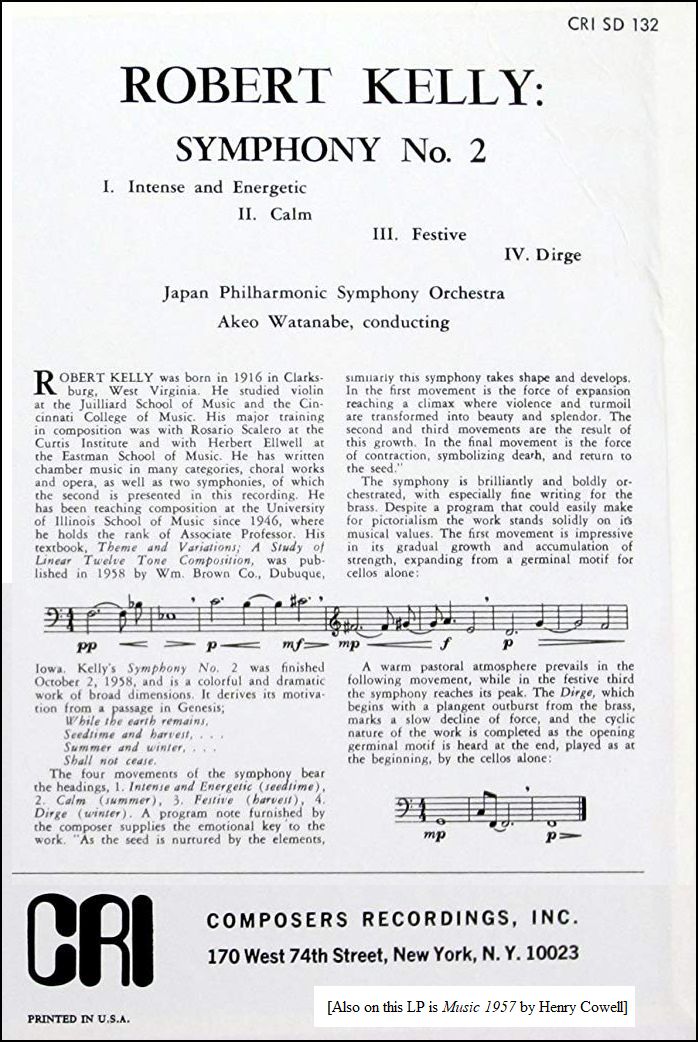

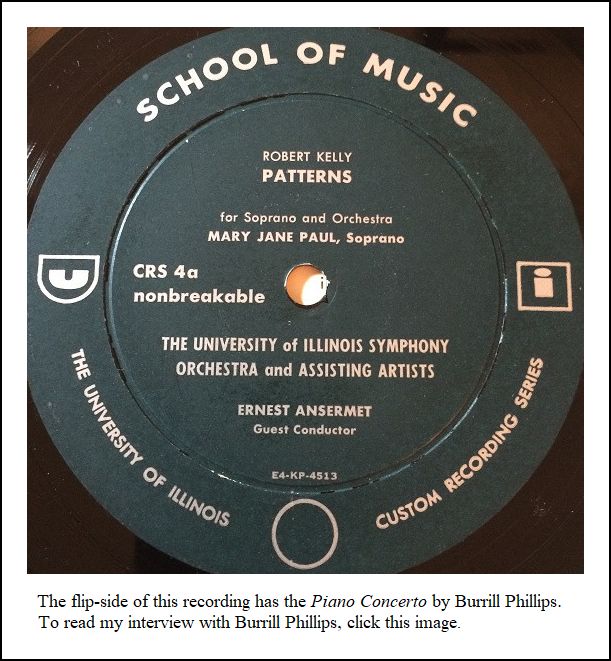

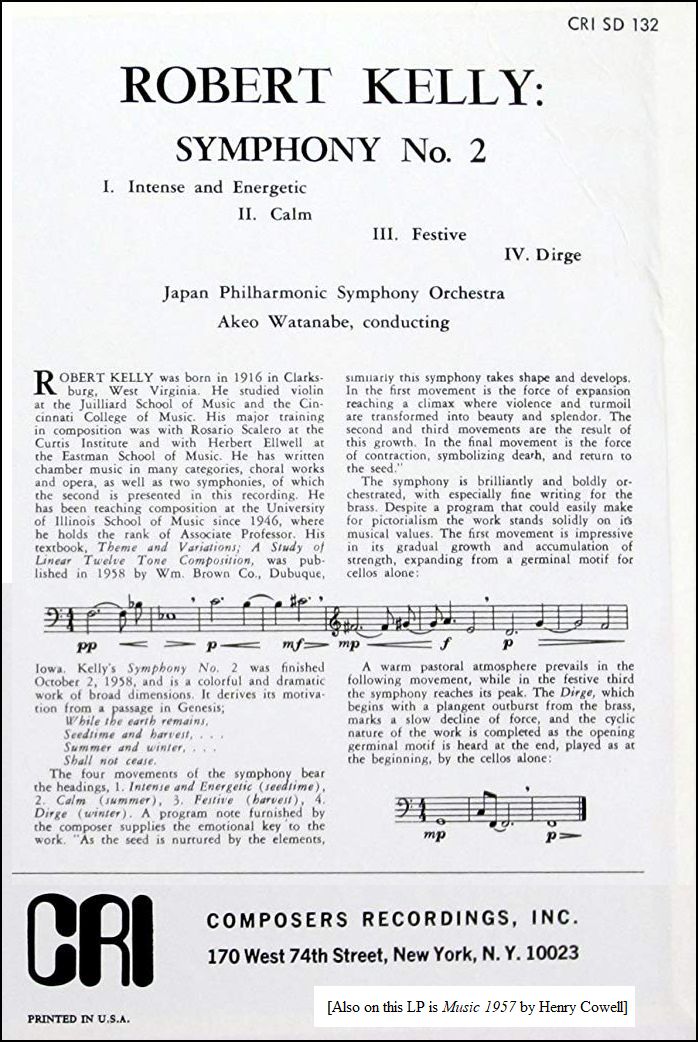

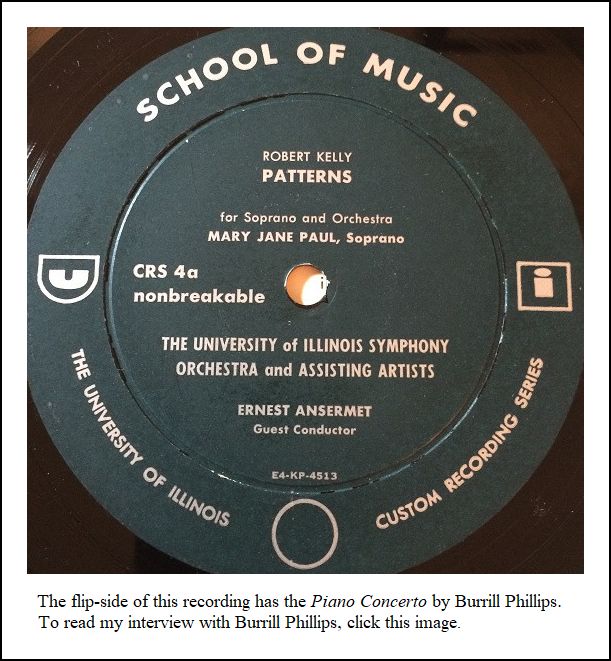

to the Second Symphony. That, and the Patterns for Soprano

and Orchestra are similar in a way. It’s what I call ‘linear

twelve-tone composition’. All the

notes are not part of the twelve-tone series, but it’s handled more

in my linear way, like the Cantus Firmus in old times. There

you have any part of a given melody, but now the melody would be a

twelve-tone melody, and the other voices that are counterpoint and harmony

against it are a free choice. Now I’m beginning to change some

to something else, and it brings us a little closer to Webern and Schoenberg,

but not completely. I start working in what I call ‘subsets’.

BD: Was it a conscious effort to move

towards Schoenberg or Webern, or was it was just an evolution of your

music?

Kelly: I’m quite a believer in evolution

of creative ideas, as well as evolution in nature. I’m a student

of nature and religion, so those have all influenced my writing.

That’s why I had that connection to Kahlil Gibran, and his first innocent

touch with God. He’s a creative artist, too. He’s not

only a writer, but he did some sculptures and things like that.

BD: Did you branch out into painting

or anything else?

Kelly: No. I could have, but I

just didn’t want to spend that kind of time. It’s hard to tell...

BD: [With hopeful anticipation] Maybe

you’ll get to it yet...

Kelly: [Laughs] Well, I don’t suppose

so. I had a student... you probably know him, Jan Bach.

BD: I have not met him yet. [I

would interview him four years later, in 1990, and it has been transcribed.

Click the link above to read that conversation.] Didn’t

he write a short opera for the New York City Opera when they did

a triple bill of new works? [This was The Student from Salamanca,

and was presented in 1980.]

Kelly: Yes. He won a prize for it.

He’s teaching at Northern Illinois University now. When

he studied with me, he was torn between wanting to be a painter or a

composer, and for a couple of years he didn’t know what to do.

He still dabbles in artistic things, like sketchings, and pen-and-ink.

But you have to make a decision if you go into these fields. I never

had too much of a decision to make, whether to a professional musician

as a performer or a composer, or both. I chose to go into composition,

which was stronger than performance... though I still perform on violin

and viola. I’m a string player, and I love to write string music.

In fact, I have a new string piece that is going to be premiered here

next Fall. I’m getting back to some of my folksong ideas, which I

wrote back in the late ’40s and early ’50s.

I kept the tune of Shenandoah, and have now set it for

strings. I’ll probably premiere it next Fall.

BD: Is your writing for strings more

idiomatic than, say, for woodwinds or percussion?

Kelly: I don’t know. I don’t think

so. I’m also a clarinetist, so I know woodwinds, and I play a

little piano. I’m also very much interested in percussion.

We have had a wonderful percussion here over all the years.

BD: Is this something you encourage

your students of composition to do — actually

learn to play many of the instruments they’re going to write for?

Kelly: Yes, but not to the extent that

Hindemith did. Hindemith was supposed to have been able to play

all these instruments that he wrote for.

* * *

* *

BD: Let me ask you about the influence

of electronics. This is a two-edged sword. First, let

me ask you about the influence of home consumer electronics, and how

has this influenced either composers or audiences over the years.

Kelly: You’re talking about electronic

music?

BD: No, that is the second edge of the sword.

Firstly, the home stereo systems, and the great proliferation of home

music systems. How has this influenced audiences or composers,

either good or bad, or both?

BD: No, that is the second edge of the sword.

Firstly, the home stereo systems, and the great proliferation of home

music systems. How has this influenced audiences or composers,

either good or bad, or both?

Kelly: I think it’s a great influence,

because you get a chance to hear the composition more than once, indeed

many times. Composers study other composers by playing their

music over while looking at the scores to see what they’ve done.

I’ve looked at a lot of George Crumb’s music.

George and I are very good friends. In fact, we’re from the

same state, West Virginia. I’ve always been very much interested in

George’s music... not that I would write like he does. He’s younger

than I am, and I have a lot of respect for him. He hasn’t gone over

into using electronic computer ideas or music... at least he hadn’t the

last time I talked to him. [Both laugh]

BD: One never knows where one’s imagination

is going to lead.

Kelly: Yes. I don’t think George

has to do that because can get sounds from a few instruments that

he finds of his own, like musical stones and things like that.

He can dig up sounds that you can’t even do with electronic music.

BD: When you’re writing a piece, are you

ever surprised where it winds up, where the composition leads you?

Kelly: Not too much.

BD: At the beginning, when you set out

to write a piece, do you know where it will eventually go?

Kelly: Yes, yes. That’s why I

say I’ve learned an awful lot of how to construct and organize music

in the last thirty years. In fact, I have based a lot of that even on

the early training I had. I can hear what I’m writing, and I

know how long this piece is supposed to be, or that I’d like it to be,

and the sounds that come out of it. Once in a while, I’ll experiment

with something, some combination that I never used before, and I just

have to use my imagination to see if this is what I want. When I

hear it, it’s pretty close to what I had thought it would be. No,

I don’t seem to have too much trouble there.

BD: You write so-called ‘classical

music’. Is classical music art or

entertainment?

Kelly: I think it’s art. Popular

music is entertainment.

BD: Is there a place for both in society?

Kelly: Oh, sure!

BD: Do you feel that classical music

should be entertaining at all?

Kelly: Oh, yes, it should be entertaining,

but not in the same sense as popular music. I Just listened

last night on the radio to some of Irving Berlin’s old tunes that they

were playing. Some of them I really think are great works.

It just surprises me and shocks me to think he could never read music.

He used his piano, but only played in one key. He had to crank

it when he wanted to change into other keys. [Berlin played

almost entirely in the key of F sharp so that he could stay on the black

notes, and owned three transposing pianos so as to change keys by moving

a lever.] Berlin had a lot of creative ideas, not

only in the music but in the words. I don’t know whether you know

much about Berlin, but he wrote his own words and music.

BD: Speaking of words, you’ve done a

couple of operas. Have you also written some songs and choral

works?

Kelly: Yes.

BD: Have you set your own words?

Kelly: Some, but not too much.

If possible, I’d rather find the poetry I like, and see if says something

to me.

BD: I want to come back to your own works

in a moment, but let me pursue this business of pop versus classic a

little bit more. Is it a mistake for audiences who go to symphony

concerts every week to draw an imaginary line between classical and

popular music?

Kelly: I don’t know. [Laughs]

BD: It seems that classical aficionados

all look down their noses at rock music.

Kelly: It depends on how far you want

to go in popular music. If you’re going into rock, and acid

rock, they’ll not want to hear it because it’s so monotonous.

BD: Have we really made a third division,

after classical and pop, and then rock?

Kelly: Yes, I think rock is something different

than popular music. When you’re talking about Jerome Kern and

Berlin, that’s one thing. But when you’re talking about others,

I mean a rock composers, all I can say is I don’t understand it. It’s

boring, and I don’t want to hear it. I don’t know how you feel

about it...

BD: I find myself not listening to very

much of it at all.

Kelly: You can’t help hearing it, as

there’s so much of it.

BD: That’s right. There’s an

over-proliferation of it.

Kelly: I won’t go into that...

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Oh why

not??? Please do! [Both laugh]

Kelly: Well, my reaction to it means

nothing now. I’d rather give reactions as to why I think serious

music writing is better than writing rock music. I have a lot

of respect for the guys who want to do rock, but I think they’re only

in it for the money.

BD: It’s just a commercial venture?

Kelly: If they can’t make the bucks out

of it, this is why it will die. That’s what happening to all this

recording business. When they’re not selling records, it’s going

to hurt all of us. Of course, the video things are coming out,

and they are all taping things.

BD: Why do you say, “It’s

going to hurt all of us”?

BD: Why do you say, “It’s

going to hurt all of us”?

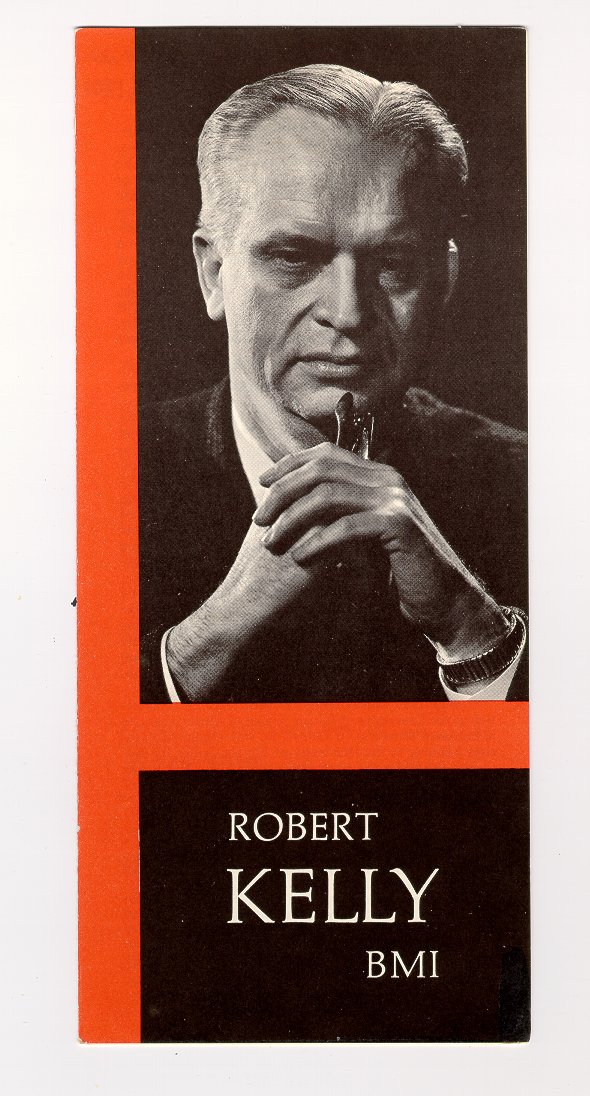

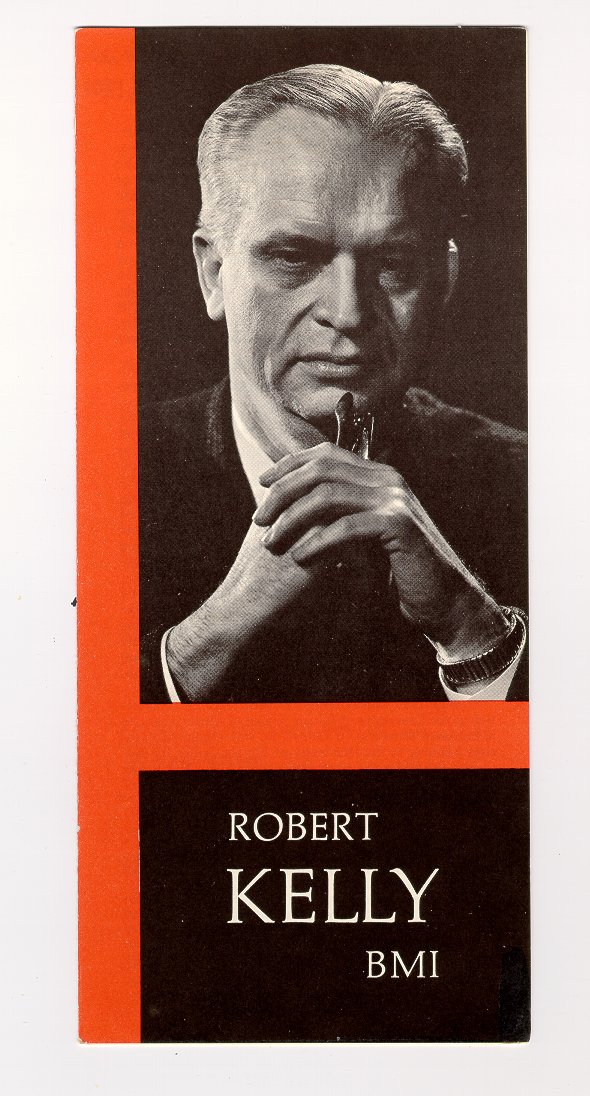

Kelly: I’m

a BMI composer, and they’re quite worried about passing laws in Congress.

Eventually it’s going to hurt the serious composer because we

get some monies from BMI, and the money comes from pop and rock music.

[Laughs] So, we’re subsidized by the rock guys. [BMI

is a music-licensing organization, similar to ASCAP. One of my

friends, baritone Roger

Roloff, was married to Barbara Petersen, Vice-President of BMI,

and she helped set up this and several other interviews with her composers.]

BD: [With another gentle nudge] Maybe

you should secretly admire the rock guys for making all the money.

Kelly: Ah, no! I don’t care what

they do. You can’t sell me any rock music if I don’t want it.

BD: Let me go back to your idea of

just a moment ago. Why is writing serious music better?

Kelly: It’s better for me, and it’s better

for other composers, most of whom are associated with university situations,

because you’re putting out your feelings for others to enjoy, or

to listen to, and be curious about. It’s just the satisfaction

you get. I compose only because I get satisfaction from creating.

If I never got a performance, or if no one ever paid attention

to me, I think I’d still write. I don’t know... I haven’t quite reached

that stage yet. [Both laugh]

BD: Has all of your music been performed?

Kelly: Most everything has been performed.

I’ve had a little trouble with this big opera.

BD: Let’s talk about that opera.

This is The White Gods?

Kelly: Yes. I had a grant from

the university for a year and a half.

BD: Was that enough time to work on

it?

Kelly: I got most of it done. It was

for a year, and I didn’t quite finish. I needed more time, so

they gave me another semester, and I still didn’t get it finished. But

they can only give out so many grants. They have to give other

people opportunity.

BD: Did you finish it up on your own,

or is it still left uncompleted?

Kelly: Oh, the opera’s finished. It’s

been finished, but the stage version’s never been performed completely.

I’ve had parts of it done in concert version, which has been a help

to promote it, but it’s going to be difficult to get it on stage because

of finances. I contacted many professional opera companies around

the country, and they’d be very happy to do it if I could raise the

funds. They cannot take it out of their budget, and so after a

while I get disappointed. Robert Ward is a good friend

of mine, and he said I’m trying to hit the top with it. He told

me to try to get it done in a university situation, like my own place

here at the University of Illinois. They would do it here, but they

can’t take it out of their budget to put it on, because it would cost from

$8,000 to $10,000 to do it. That would pay for some of the orchestral

musicians, the stage sets, the costumes, and maybe hire a few singers.

I’m not able to come up with $10,000. I’d like to, but I have

not found an angel yet.

BD: Is this something that will discourage

you from writing more operas?

Kelly: Yes. I’ve written two

operas, and one was the folk opera, which is a one-act. It

didn’t take much to put it on, and it was premiered in Norfolk, Virginia.

Then we did it here, and did it on TV. It didn’t take more

than a $1,000 to put it on. It’s a one-act opera, but I don’t

think I’ll write any more operas because I’m getting too late in life

to take on a big one. I have a poet friend of mine who desperately

wants me to write an opera to his text, and I said to him there’s no

way. I said he needs to get a young guy like Jan Bach, and see

what he’ll do.

BD: Are the monetary considerations

going to even discourage young people like Jan Bach from doing things

like that?

Kelly: So far he’s been doing pretty well,

and he’s writing a full-length opera right now. I’m just wondering

what problems he’s going to have. When you’ve got to put on a

full opera — a tragic opera with

all the forces including chorus, orchestra, and big sets

— you’re running into expense,

and I don’t recommend it for anybody today. It’s just too expensive.

BD: Would you set this man’s text to

music as an opera if the expense were not a problem?

Kelly: I doubt it.

BD: [Wistfully] If you won the

Illinois Lottery, would you then go and do it?

Kelly: [Laughs] If I won the Illinois

Lottery, I’d put The White Gods on. That’s my interest

right now. If there’s anything I want to do with that kind of

money, it is to put a reduction on of this work. I’d only do it

in the university situation where it would cost less, and not try to do

it professionally.

BD: Is this not something you would

want Lyric Opera of Chicago to produce?

Kelly: Oh, if you could get the funds,

I’d be very happy for it to be done there. I think it’s a great

opera. It’s sung all the way through. There are no speaking

parts in it at all. It’s about the Aztecs, and the conquest. It’s

a very colorful opera, and in this case, it’s a very rhythmic.

I assume you know Roger Sessions’ Montezuma. Well, this is

just the opposite of what Sessions did. Sessions is on the Spanish

Conquest, and mine is on the Aztec view of the Conquest. It’s an

entirely different thing regarding both in ideas and musically. Sessions

tried to write twelve-tone music, and Aztec music was not twelve-tone.

It was pentatonic, just like Oriental music. So, my opera, at least

for the Aztec Indian part of it, is pentatonic.

BD: You purposely used their kind of

music to give it that flavor?

Kelly: Yes, definitely. I did two years

of research on this, and I came up with a lot of good ideas.

I didn’t just work on this while I was on that grant. I worked

on it for several years before. A friend of mine wrote most of the

libretto. It was going to be a two-act opera, and I realized it

needed to be three acts. The first act to present the Aztec culture,

and I couldn’t get him to do any of it. By then, too much time had

gone by, so I wrote the libretto myself for that first act. I think

it can be a very successful opera, but you’ve got to have the forces for

it, and the money to put it on. Have you got any connections with

Lyric Opera?

BD: [Sadly] I just do interviews,

I’m afraid. I don’t have the ability to push works on the management.

Kelly: I don’t know how much they’re

interested in doing premieres. I know the Penderecki [Paradise

Lost] was a world premiere... [That work was commissioned

for the US Bicentennial (1976), but was delayed and premiered at Lyric

Opera in November of 1978, with the production taken to La Scala

two months later.]

The General Director of Lyric Opera,

Ardis Krainik,

presented what she called Toward the Twenty-First Century, an

initiative to present new works, as well as revivals of operas from earlier

in the Twentieth Century. Using both the main company, as well as

the Lyric Opera Center for American Artists, composers of premieres and

recent works included Philip Glass, Hugo Weisgall,

Dominick Argento,

William Bolcom,

Carlisle Floyd,

John Corigliano,

Gian Carlo Menotti,

Luciano Berio,

Anthony Davis,

Marvin David Levy,

John Harbison,

John Adams,

André Previn,

William Neil,

Leo Goldstein,

Bright Sheng,

Bruce Saylor,

and Shulamit Ran.

These last five were named as composers-in-residence, and besides

the other established composers mentioned, Gunther Schuller and

Stephen Paulus

assisted in the selection of the budding talent. Also of note

was critic Andrew Porter,

who wrote the libretto for the Sheng opera.

|

BD: [Trying to be helpful regarding a production

of The White Gods] Send it to Bruno Bartoletti.

He’s the Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of Lyric Opera.

Send to him a score and tapes of what’s been performed.

Kelly: Yes, well, I’ve done that for so many

places, and I get the same answer. They’d just love to do this,

but can I find funds for it? I’m the guy out there who has to

get the money. If I won the Lottery, as you said, there it is,

and we’d have it on stage. No question, and I could have my

own choice of opera company. [Laughs] They wouldn’t like

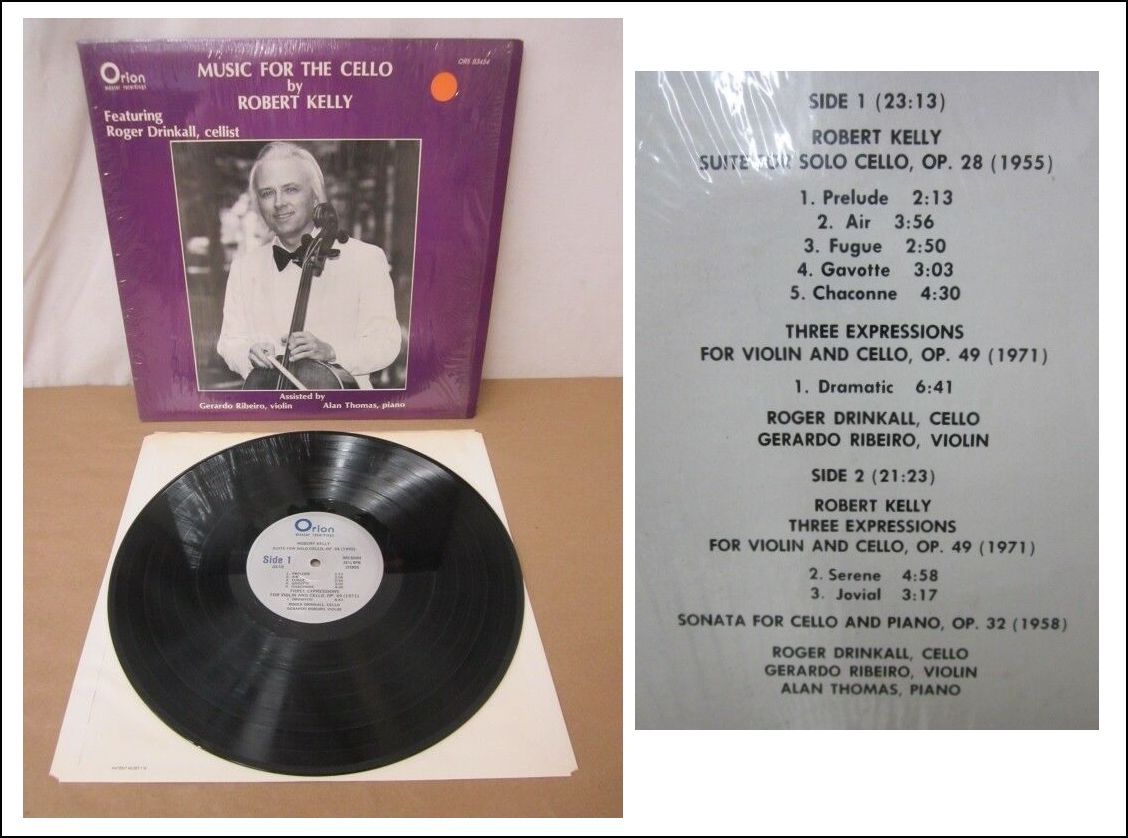

that, but if it’s my money, it’s the way it is. I’ve done things

like that before. I put out my own money, and in fact that’s how

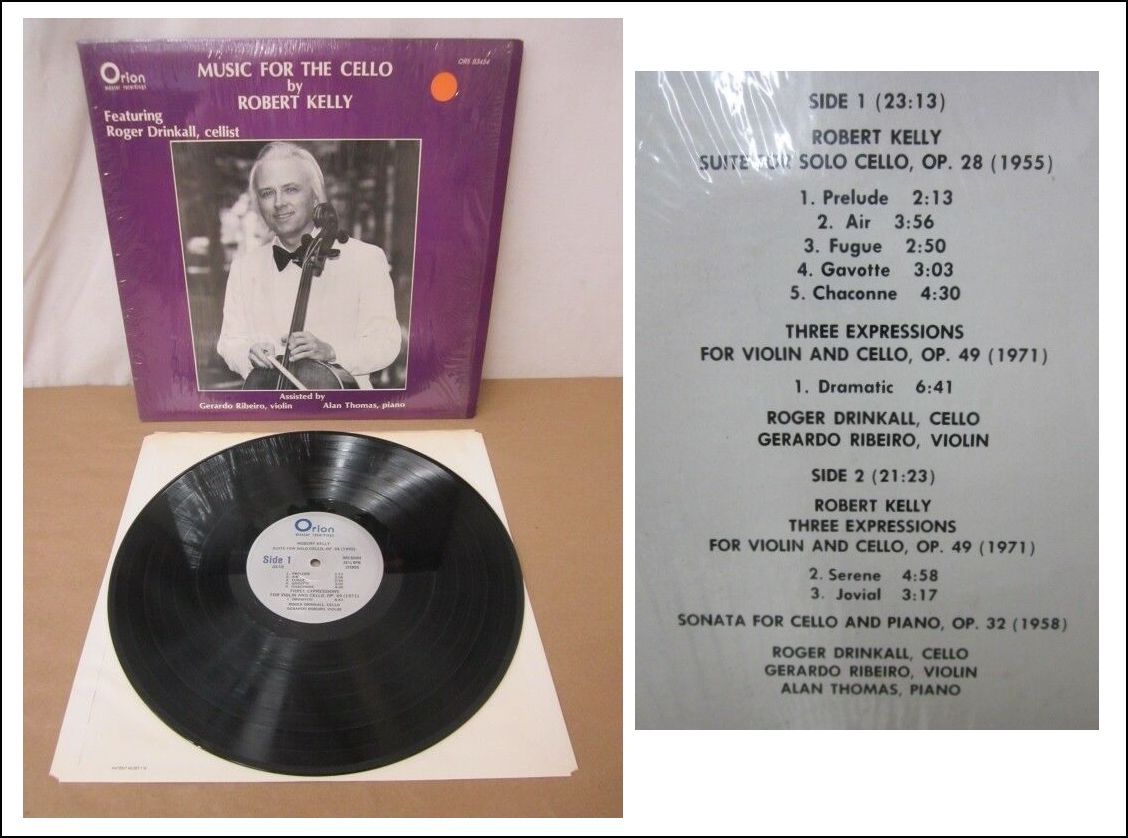

the recording for cello came about. Orion wanted it, but I had to

put up the money, so I called the shots. I went down to Florida.

I had an engineer down there, and we did all the recording sessions.

We came up with a very fine tape. It’s just one of those records

that will not sell much. Who wants to listen to a pile of cello

music?

BD: But you yourself are pleased with

the result?

Kelly: Oh, yes, the record is very good.

I’m just a little disappointed it in because Orion hasn’t been able

to move it and get critical reviews on it. I got a lot of good

critical reviews on the Second Symphony when that came out. Fortunately,

I didn’t have to put in money at all.

BD: What’s the role of the critic?

Kelly: To listen to the music, and be honest

about what he hears and how he feels. I don’t know what’s happening

with this cello record. Orion said that they sent out. They

gave me the list of twenty-five or thirty critics, and on the contrary,

it didn’t get one review. I just don’t understand it. It’s

either they don’t have much respect for Orion and what they put out, or

they’re just not interested in cello music. I really don’t know what

the racket is in this profession of critics, and getting records, and

writing reviews.

* * *

* *

BD: Your Second Symphony has been performed

a number of times under great conductors. Do you find that the

big-named conductors get more out of your music than perhaps university

orchestras, or university conductors?

Kelly: Oh, yes! The performances I’ve

had with Stokowski and Szell, and even Mitchell in Washington DC

have been great.

BD: Did they find things in your music

that even you did not know were there?

Kelly: I don’t really think so. They gave

it a better performance than a lot of others did. They were

very sympathetic with what I was trying to do. We had some discussions

during the rehearsals, asking questions, which I found were very helpful.

Even when Rafael Kubelik was here, he was very helpful, and made some suggestions.

So did Ansermet. I have a great respect for these people.

I will listen, and sometimes I’ll change something in the score because

they suggested it... and sometimes I won’t.

BD: What kinds of suggestions did they make?

BD: What kinds of suggestions did they make?

Kelly: When I was in Cleveland,

and George Szell was rehearsing the Miniature Symphony, he

asked me to come up on stage. So, I sat up there, and the first

thing he asked me was if I wanted to conduct. I said, “Goodness,

no! I came to hear you conduct it!”

I know a couple of guys in the orchestra, and they told me that I was very

wise. Most composers, when Szell does that to them, take the stick.

He knows exactly what he’s got to work with. The concert master,

Josef Gingold, made a couple of suggestions. I’m a violinist,

but he made a couple of suggestions about some bowings for the first

violin part, and they were marvelous. I thought it was great,

so I said to do it. The score was published shortly after that,

and his bowings are in there. I’ve had other suggestions. When

we did Patterns, Ansermet made some suggestions about the trumpet

part. A lot of it had to do with dynamic levels being too high

for this particular passage. I said his ideas were fine, and later I changed

it in the score. Kubelik made a suggestion in the Miniature

Symphony. In the last movement, which was in 4/8, he said it

would be much better just to change the 4/8 to 2/4 meter, and he conducted

it that way. We tried it, and it was a good idea. So, that’s

the way it came out when it was published. You can learn a lot from

conductors and performers. They’ve been my teachers for all the years.

Like any student, you listen, you accept or you digest it, or maybe even

reject it. I’ve rejected ideas, too. Thomas Shepard used to

have a chamber orchestra in New York, and he was going to think about doing

Patterns after it came out. He wrote to me and said he liked

everything except the way I ended it. He said if I change it,

he could probably program it. So I wrote him back, and said I cannot

change it. “It’s the way I feel about it,

so if you won’t perform it just because I won’t change it, that’s the

way it is.” So, he never performed it.

I wasn’t going to change the music, because it was the whole concept

of it at the end. It wasn’t me, it was him.

BD: That’s too bad. I’m sorry

that he wouldn’t at least give it a shot, even with the ending he

didn’t care for.

Kelly: That’s the way he felt about it.

My mind was made up. I would not change it just for a performance.

BD: Might you tamper with a detail here

and there, but not recast the last five minutes?

Kelly: Yes, but it wouldn’t have changed

the idea he wanted. I had a feeling maybe he didn’t like the

interpretation of it. But I’ve had other people come up

to me who knew Amy Lowell’s poem Patterns, and they said my piece

was a beautiful setting of it. It seemed to fit the words right,

and they were quite pleased with it. I have had more comments from

people on music where I’ve set poetry for songs and cantatas, which is

very gratifying to me when you get those kinds of comments from people

who know the texts. Walden Pond is a later work [called

an Environmental Cantata], for mixed chorus, percussion, flute, narrator

and soprano. I took the text from Thoreau, of course. You could

call Thoreau an environmentalist, and that’s the way I feel about life,

too. So, when I get great comments from people who feel the same

way about Thoreau as I do, I feel pleased.

BD: You sought out poetry that meant something

to you.

Kelly: Oh, yes. It was all my

idea to do this. I wasn’t commissioned. That’s where

I write my best music, when I just use my own ideas. Somebody

commissioned me to write a saxophone concerto. In the first place,

I’m not crazy about saxophone, and the second place I don’t care about

somebody paying me $2,500, which is too much, to write the kind of a

piece where he tells me how he wants it. He wants it this way, this

way, and that way, and I said I am not that kind of a composer.

I am not a tailor where you go in and order a suit.

BD: [Musing on the idea] It takes various

kinds of composers...

Kelly: Have you heard this kind of viewpoint

from many of them?

BD: Some of them take the commissions,

and try to work with the performer a little bit.

Kelly: Oh, I’m OK with that, but I don’t

feel it’s my best work after it’s done, because there’s another person

involved in it.

BD: For you, music is much more personal?

Kelly: Yes, yes, definitely.

BD: Do you expect your music to last, and be performed

a hundred years from now?

Kelly: Who’s going to say? I’m

having enough trouble to get it performed right now! [Both laugh]

Every composer feels the same way — that

he didn’t get as many performances as he would have liked.

BD: Are there enough young composers coming along...

or perhaps too many young composers?

Kelly: I got the surprise of my life when I became

a student of composition — and

then as a teacher — that there were

so many other American composers around the country. It overwhelmed

me that there were so many, and that’s never ceased. It’s

just multiplying like rabbits, even today. You see these lists

of younger composers coming up, and some of them are making it, some

of them are not. I’m talking about younger ones in their 20s and

30s.

BD: Is there room for all of them, even the good

ones?

BD: Is there room for all of them, even the good

ones?

Kelly: What do you mean by room?

Enough to make a living?

BD: Yes.

Kelly: Then yes, if you can get into some kind

of a job that will give you money, like teaching or playing in a symphony.

I had two choices when I was coming up — either

teach, or play in a symphony. You can’t make it financially as

a composer, at least not too many can. Maybe Aaron Copland or

Samuel Barber, although Sam was teaching at Curtis when I was there.

But he didn’t make his money from composition.

BD: Are there some great composers

coming along? Is there another Aaron Copland in the pipeline?

Kelly: Who knows? It depends on the breaks

that you get. Even some of the best composers don’t get the breaks,

and some of the composers who have the talent don’t have the initiative,

or the push, to get out there and sell. It’s awfully hard to sell

the product when it is something that you’ve created... at least it is

for me. I’ve done very well with that, but I don’t feel I’ve done

as well as some people who stayed around in the New York scene.

I had a choice to make when I was younger — stay

around in the New York scene, or get out here in the cornfields of central

Illinois.

BD: Do you think you made the right

decision?

Kelly: Definitely, because it isn’t just for me

as a composer. It’s for me as a family man, and having children.

I could not see raising children in the New York area. I went

to school there for a while, and I know what the environment is.

I didn’t want to raise children in that kind of environment. It

just wasn’t fair to the children. You’ve got to think of somebody

else besides yourself. I’ve gotten quite a lot of breaks by not living

in New York. I’ve a lot of friends there, and I get some help with

performances. I’ve had more performances in New York than I’ve had

in the whole country, though I’ve had other spots where I’ve had a lot

of performances around the Mid-West, and a few in the South.

BD: Do you know all the performances

of your music that go on?

Kelly: No. I wish I did know, or that they’d

be reported to BMI, because we get credits for everything. Somebody

called me from New Jersey the other day... I have a work for piano and

percussion called Diacoustics [Op. 48] which is played quite a

lot in the percussion field. It’s a very difficult work, and it’s

a virtuoso-type piece, and they called me and they said they had lost some

of the parts. They wanted to know to get a hold of them. I said

I didn’t have any parts, but my publisher did. I asked if they had

a percussionist to perform it, and they said they’d been playing it.

I didn’t even know that this work was being performed. Sometimes

the information gets out in percussion magazines, which I go through, and

I see where things are performed.

BD: Does it ever surprise you that

a piece is being performed in some odd place?

Kelly: This piece does because it’s

very difficult. It was premiered in New York by the

Manhattan Percussion Ensemble. We had it done here, and a lot of

the big schools have percussion departments, and have done it.

But it still surprises me when it is done. They must have a

pretty good percussion department, that’s all I can say. It takes

fourteen or fifteen good players, besides a good pianist, and it runs about

twenty-two or twenty-three minutes. [After a slight pause]

I certainly appreciate all this. Is this supposed to be for

my seventieth birthday [which was coming up about six months hence]?

BD: Yes, that would be the first use. [At

this point we talked a bit about the specific pieces I would be able

to play on the radio, and he was sorry that Diacoustics was not

available on a commercial disc. The four LPs I had at that time

are shown on this webpage.]

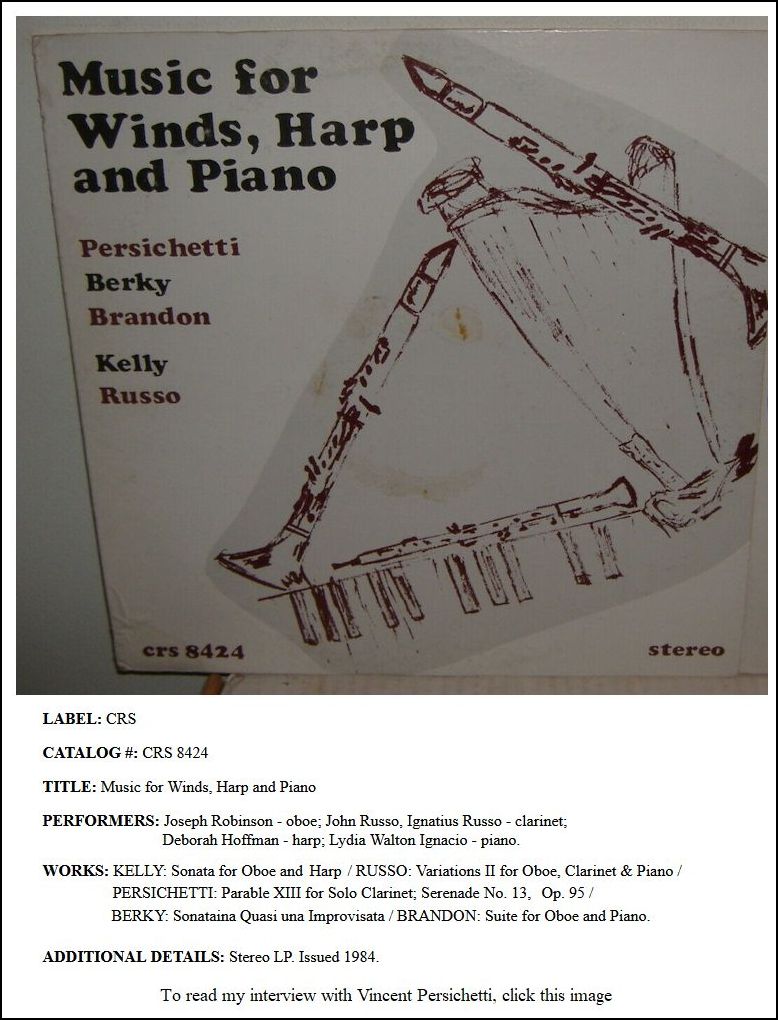

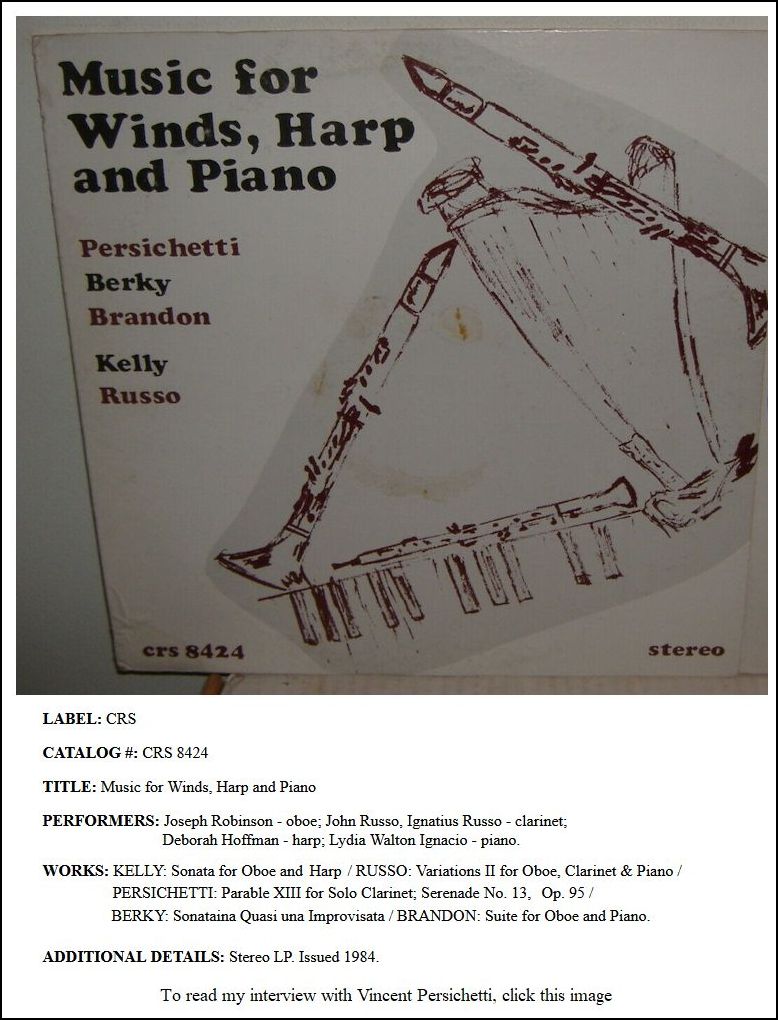

Kelly: I hope you’ll do that Sonata (for oboe

and harp), even though it’s an old work. Joseph Robinson is

a great oboist, and the harpist is very good too.

BD: As I look at the various pieces,

this seems to be a nice balance — one

of the cello pieces, the Sonata, and then the Symphony.

That would make up a nice program, unless you object...

Kelly: Oh, I don’t object to anything

you’re going to do!

BD: Is it a good feeling to know that you are

going to be seventy?

Kelly: Yes. [Bursts out laughing] I

don’t pay much attention to age. It doesn’t mean a whole

lot to me. It depends on how you feel, and I’ve been feeling

very good. But age is kind of deceptive. You could be fifty

and feel washed out, or even younger, and you can be ninety and feel

great.

BD: I hope you get to be ninety and

still feel great.

Kelly: Thank you very much. I

hope you do too! [Much laughter] I appreciate you thinking

of me for your program.

========

========

========

--- --- ---

---

======== ========

========

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on March 8, 1986.

Quotations (read by BD) were included in programs on WNIB in 1986 and 1996.

This transcription was made in 2020, and posted

on this website at that time. My thanks

to British soprano Una Barry for her help

in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this

website, click here.

To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print,

as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until

its final moment as a classical station in

February of 2001. His interviews have also

appeared in various magazines and journals since

1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited

to visit his website

for more information about his work, including

selected transcripts of other interviews, plus

a full list

of his guests. He would also like to call your

attention to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

BD: Let me start by asking you

how the teaching of young composers has changed over that time.

BD: Let me start by asking you

how the teaching of young composers has changed over that time. BD: You went off into your own style?

BD: You went off into your own style? BD: No, that is the second edge of the sword.

Firstly, the home stereo systems, and the great proliferation of home

music systems. How has this influenced audiences or composers,

either good or bad, or both?

BD: No, that is the second edge of the sword.

Firstly, the home stereo systems, and the great proliferation of home

music systems. How has this influenced audiences or composers,

either good or bad, or both? BD: Why do you say, “It’s

going to hurt all of us”?

BD: Why do you say, “It’s

going to hurt all of us”?

BD: What kinds of suggestions did they make?

BD: What kinds of suggestions did they make? BD: Is there room for all of them, even the good

ones?

BD: Is there room for all of them, even the good

ones?