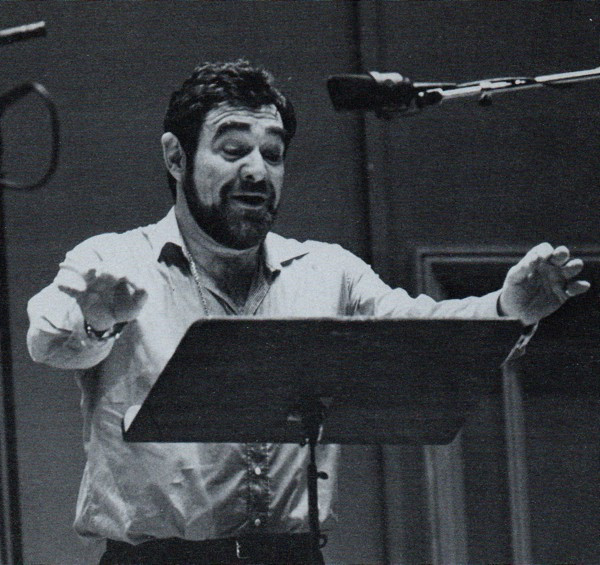

Baritone Jean - Philippe Lafont

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

Jean-Philippe Lafont (born 11 February 1951)

is a French baritone. He studied in his native city of Toulouse and later

at the Opéra-Studio in Paris. He made his operatic

debut as Papageno in The Magic Flute at the Salle Favart, Paris

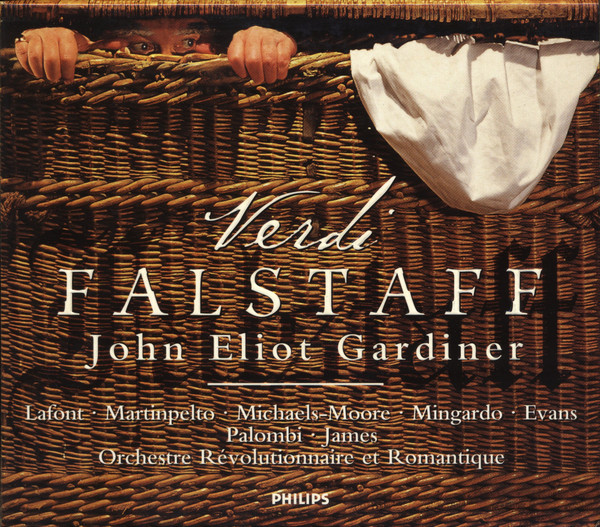

in 1974. He went on to appear regularly in Toulouse, where he first played

the title role in Verdi's Falstaff in 1987.

Lafont has performed at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, Carnegie

Hall and the Metropolitan Opera in New York, La Scala in Milan and the

Royal Opera House, London. Among

the roles with which he is particularly associated are the four villains

in The Tales of Hoffmann, the Comte des Grieux in Manon,

Golaud in Pelléas et Mélisande, Barak in Die Frau

ohne Schatten and the title roles in Gianni Schicchi, Rigoletto,

Boris Godunov and Macbeth.

|

Baritone Jean-Philippe Lafont made his debut with Lyric Opera of Chicago

in September of 1993, singing Sancho in Don Quichotte of Massenet.

Samuel Ramey was

the knight-errant, and Susanne Mentzer was Dulcinée.

John Nelson (also

making his Lyric debut) conducted, Leslie Koenig (again, a Lyric debut)

directed the production designed by Pier Luigi Sammaritani.

Lafont would return to Lyric for Michele in Il Tabarro, Prospero

in Un re in ascolto [Berio], Scarpia in Tosca,

Tonio in Pagliacci, the High Priest in Samson et Dalila,

and the Forrester in Cunning Little Vixen. He would also participate

in one of the gala concerts at Millennium Park.

During his first visit, Lafont graciously

agreed to meet with me in an evening between performances. His English

was fairly good, and I had no trouble understanding his thoughts and ideas.

We spoke of many musical topics, and after airing a portion on WNIB,

I am pleased to mark his 75th birthday by presenting the entire conversation.

Bruce Duffie: Thank you for seeing me this

evening. Tell me the secret of singing French opera.

Jean-Philippe Lafont: Oh, the secret! It’s

necessary for a French singer to sing first the French repertoire, of

course. We haven’t a very big repertory. We are not like

the Italians who have a lot of very good operas.

BD: [Surprised] You don’t have a lot of

very good operas???

Lafont: Not very many, and not like the Italian

or German repertoires. We have some by Berlioz and Massenet, and

then there’s Debussy, but he wrote only one or two, and only one is a

very good work, Pelléas et Mélisande. But the

other composers are not so good, like the works of Verdi, Puccini, Rossini,

Donizetti... When it’s possible, I want to sing a good one, like Don

Quichotte. It’s normal to sing it.

BD: We’ll come back to Massenet, but I know you

did Christophe Colomb of Darius Milhaud. Is that a good work?

Lafont: [Sighs] He’s not my favorite composer.

BD: Do you sing the title role?

Lafont: Yes, the title role. I accepted

it because it was the first time for me in San Francisco, and because it

was Milhaud. I know his wife. She’s very old now, but I met

her in Paris. At that time, I was a little bit free, and I accepted

for all these reasons. It’s very important for us to sing in the USA,

and for the American singers, it’s very important to sing in Europe.

[Both laugh] As we French say, “Nul n’est prophète en

son pays,” which means no one is a prophet in their own country. It’s

always the case that strangers are better. It’s not true very often,

but it’s like that. So for us, it’s very important to go to the

USA. When we come back, the directors in the French opera houses

look at us differently. It’s stupid, but it’s like that.

BD: C’est la vie [that

’s life]!

Lafont: C’est la vie, but it was a very

good experience.

BD: Is it a role that you would like to sing

again, or would you rather not?

Lafont: If the Metropolitan were to ask me to

sing it once more, of course, or San Francisco, okay, but otherwise I

don’t think so. The stage director, Lotfi Mansouri, whom

I liked very much, did very good work with this opera. It was semi-staged,

and it was very interesting. Everybody was very happy, but the public

not so much. At the end, the applause was very polite, as if to

say that everybody is good on stage, but bye-bye. We want to go

home! [Laughter] It’s a very difficult work. But I love

San Francisco. I didn’t know the city, but it was a good experience,

and it was good for me because Bill Mason came to hear

me to engage me for this Don Quichotte. I didn’t

know he was coming...

BD: Is it better to sing and not know that people

out there are looking you over for future engagements, or would you rather

know they are in the house?

Lafont: It depends, but that’s

not a problem for me.

BD: How are the acoustics in the house here in

Chicago? Can you the feel the voice well?

Lafont: It’s a very good one. I like it

very much, and I can say to you that I don’t like so much the Metropolitan

acoustic. I sang Carmen there three years ago, and it wasn’t

the same. I have now stopped singing Escamillo because it’s not

a very interesting role, and because I am a little bit too big to be a

toreador. [Laughs] The public thought maybe I was the bull

and not a toreador. It’s a very famous opera, but this role is not

very interesting.

BD: A good aria, but that’s all?

Lafont: Yes.

BD: How do you decide which roles you will sing,

and which roles you will decline?

Lafont: Fortunately, I have one or two people

in my life who are very smart and very clever. I also have my singing

teacher at the Paris Opéra. I am forty-two, and she has known

me and my voice for twenty-one years. So we decide some years before

what I could sing in two, three, four, or five years. For example,

I find and learn one opera each year for future. I learned Rigoletto

five years before I sang it for the first time two years ago in Bonn, Germany.

Before that I wasn’t ready to sing it.

BD: You weren’t ready vocally?

Lafont: Yes. We must open the score, and

we must close it. In France, a lot of people said Lafont’s famous

but he can’t sing Rigoletto. At that moment it was true. It

was impossible for me! But when it would be possible for me, I

will be ready. Another example... A lot of directors have

asked me to sing the Wagnerian repertoire. I’m not ready. My

voice is now ready for Don Quichotte, for Verdi, etc. The color

of the voice is right for those, but for Wagner, it’s too light, and at

my age, my personality, my knowledge of life is not enough.

BD: So, are you putting it off, or will you say

never?

Lafont: [Thinks a moment] If it’s a stupid

proposition, I would say never. Once I said never for Pizarro in

Fidelio. It’s too heavy for me. [He would later

record the role in the 1806(!) version of Leonore.] A lot of

directors think I am a bass-baritone, because my voice for a baritone

is a little bit dark. But for a bass-baritone, it’s not dark, and

a lot of people make a mistake because the tessitura and the color are

two different things. One can be a baritone with a dark voice, and

one can be a bass with a light voice, and a lot of people mix them up.

BD: You’re a higher baritone with a darker voice?

Lafont: Yes.

BD: That makes it a very specialized group of

roles that you’ll want to do.

Lafont: Yes, and for the success of a career,

it’s very important to choose very well, and for this reason it’s very

important to learn to say no.

BD: Do the French roles fit your voice very well?

Lafont: I would like to sing very soon Massenet’s

Hérodiade and Thaïs. I know these two

roles, and I am waiting for the opportunity. Sancho in Don Quichotte

is a little bit of a comic role. I began with comic roles, and

it was very difficult for me to change the mentality. When my voice

changed, inside of myself I wanted to sing, for example, Golaud in Pelléas,

and Scarpia in Tosca. But when I said that, a lot of people

said I was a comic singer, a buffo.

BD: You had been type-cast

Lafont: Yes, and there it was. It was a

little bit difficult and, for this reason, still some directors don’t

want to propose some roles like Hérodiade in France.

It’s very difficult to change a mentality, and if I accept the first time

for me this Don Quichotte, it’s because it’s a little bit of a comic

role, but it’s a very deep role. One can show a very deep sensibility,

and this I like. It was also the first time for me in Chicago, and

its theater is famous, so I had to come.

BD: We’re glad that you’re here.

Lafont: To come here, I canceled La Forza

del Destino at Marseilles. The director of the opera house

in Marseilles is a friend of mine, and I asked him for freedom to withdraw,

and he said it was okay. I like to come to your country because we

work well... not so much at the Metropolitan Opera, because it’s a factory

not a theater.

BD: How much rehearsal did you have here?

Lafont: Three weeks! I like that.

When I go on stage I want to be sure of everything. 100% is impossible,

but with three weeks of rehearsals, 90% is possible.

BD: When you get a role ready, do you ever add

anything new in the second or third or fourth performance?

Lafont: Yes, of course! Every time we must.

We must find another feeling, and the public is always different.

I feel it very much. When I go on stage, I feel the atmosphere,

and it’s very interesting. The moves are the same, but I paint the

character a little bit differently every night. If not, it’s not

so interesting.

BD: It becomes routine?

Lafont: Yes.

* * *

* *

BD: Let’s talk a little bit about Massenet.

Was he a good writer for your voice?

Lafont: Yes, absolutely. For my voice, it’s

the best. Just this morning, I thought that! I was alone,

and I thought it’s really Massenet that is the best writer for my voice.

In Don Quichotte, it’s a little bit different. It’s not

so much the voice that is important, not like in Thaïs, or

Hérodiade, or Manon. The voice is a little bit

less. It’s more acting. Sancho hasn’t got any very big arias.

He has two or three, but they are very short.

BD: Would you ever want to sing the title part?

Lafont: Me, Don Quichotte??? [Laughs] No,

I am not the right voice for that. It needs a bass. It is

a big, fantastic role. Once in Amsterdam, I sang a Spanish opera,

El Retablo de Maese Pedro [Master Peter’s

Puppet Show] by Manuel de Falla. There the title role is a baritone,

and he is Don Quichotte. [The role was created by Hector Dufranne,

who sang for many years (1910-22) with the Chicago Grand Opera Company,

and the Chicago Opera Association. (See my article Massenet, Mary Garden,

and the Chicago Opera 1910-1932). Dufranne also created

other roles, including Golaud in Pelléas.] There are not

a lot of human roles. Most of the characters are done by marionettes.

The marionettes dance around, [laughs] and one or two days after the premiere

the critics said I had a lovely voice, and my acting was good. [Musing]

I was a sports teacher before I sang. I was teaching in a university.

I taught other young teachers for two years, and I practiced French rugby.

I was into athletics, and I did the decathlon.

BD: [Coming back to Massenet] How is Massenet

different from Verdi or Puccini?

Lafont: Very often, the French repertoire is quite

heavy. In Massenet, the orchestra is very, very loud. For

me, Massenet is the composer who is closest to Verdi, because he writes

long musical phrases. You need good breath control and a good

legato. For example, the role of Don Quichotte has very long phrases,

and for these it is a little bit like Verdi. Massenet is also a little

bit like Puccini because the Verdi orchestra is not very heavy. Verdi

knew voices very, very well. It’s impossible to break voices in Verdi.

It’s possible to break them in Wagner, of course. Puccini is

also very dangerous, and Massenet is a little bit dangerous sometimes.

I prefer Verdi and Puccini, but I’m French so I must defend Massenet. But

I like him very much.

BD: Let’s talk about some of the other roles.

Do you sing Albert in Werther?

Lafont: I sang it some years ago, but now it’s

a shame for me to sing this role because a young baritone can sing it,

and I don’t like to take the work of others. It’s not so interesting

for me now to sing this role because it’s not so musically and vocally

satisfying. It’s not a very interesting role.

BD: It’s not a long role. In the nonexistent

Act Five, after Werther has gone, is Albert happy with Charlotte? Are

they happy together?

Lafont: Maybe yes, maybe not. It depends

on the stage director. [Both laugh] I also sang Manon,

and Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame.

BD: [Surprised] You sang the title part

of Le Jongleur???

Lafont: No, the Jongleur is a tenor. I

sang a priest, but everybody’s a priest.

BD: Here in Chicago in the 1930s, Mary Garden

sang the role of Le Jongleur, and according to the critics, it was a good

role for her.

Lafont: [Amused at the idea of Garden doing that

role] I sang very often a duet and arias of Thaïs and

Hérodiade, including at the opening of the Bastille Opera.

But now everywhere, when I go into the theater, I ask to the director

to please do Hérodiade or Thaïs.

BD: What other Massenet roles are there for you?

Lafont: For me, that’s all right now. Covent

Garden wanted me for Cendrillon, but I wasn’t free. I would

like to sing it, but it’s very rarely done. I would like to sing

Werther...

BD: The baritone version?

Lafont: Yes.

BD: They did that in Seattle with Dale Duesing. He

had a photocopy of Massenet’s score with the changes.

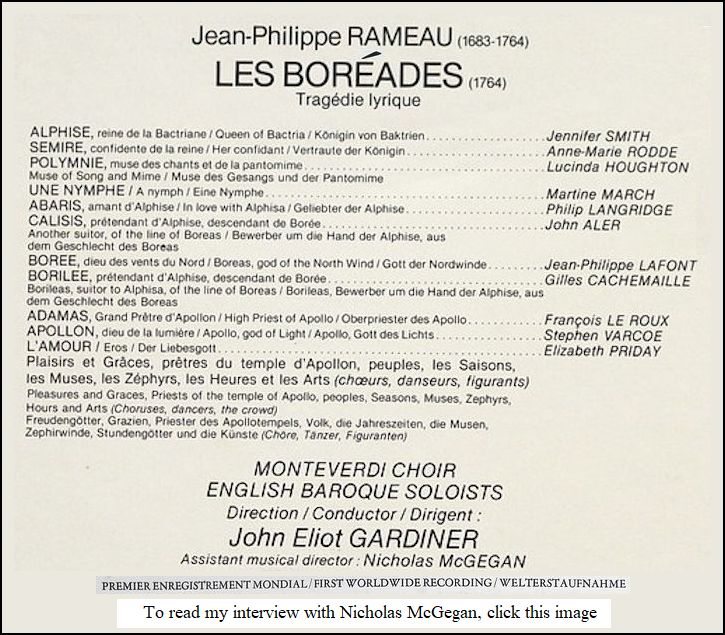

Lafont: A friend of mine, François Le

Roux said he’d like to sing this role. I think it’s better with a

tenor, but it’s a matter of taste. But I would like to do it.

I like the role of Werther. I have also sung The Pearl Fishers

very often. I have also sung Le Cid of Massenet with Plácido

Domingo. I was Le Roi, the King. [Thinks a moment] I

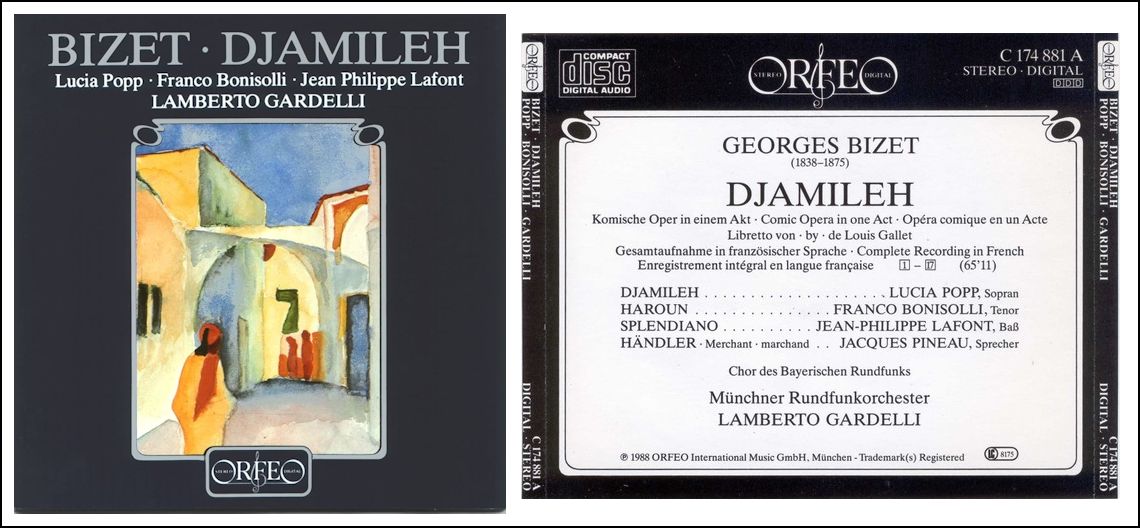

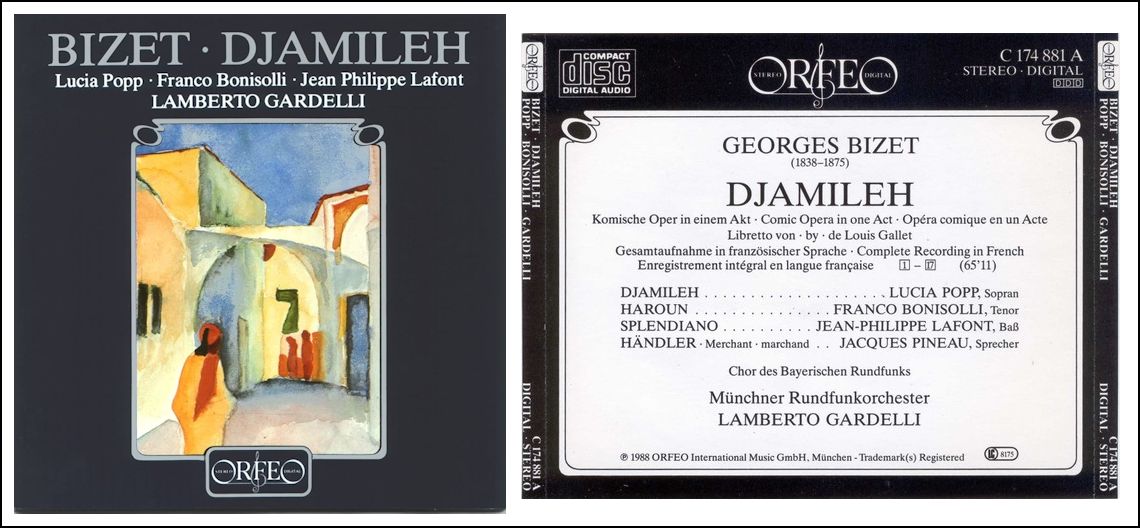

also did Djamileh by Bizet. My favorite opera is Pelléas

et Mélisande. I sang Golaud very often, and I think it’s

my best role.

BD: Tell me about Golaud.

Lafont: He has a very strong personality.

He’s a good man, and when he meets this woman, his life changes. This

woman is stronger than he is. He is lost, and if he appears to be so

hard at the start, it’s because his pain inside is too big, and he doesn’t

know what to do, or what to think, or what to change.

BD: Is it the fault of Mélisande

that she is too strong for Golaud?

Lafont: It depends. In France, very often

everybody thinks that Mélisande is a bad woman, but I think it’s

stupid to see her like that. She is also lost. For me, Goulaud

and Mélisande are too people who are lost in the forest, but also

in life. Their ways are different, but both are lost. They want

to go together a little bit in life, but it’s impossible because their culture

is different, and their age is different. It’s a little bit simple

what I say now, but it’s the difference of two people who are very far apart.

They are very distant. For Mélisande, it’s impossible

to live with Golaud.

BD: If she had met Pelléas first, could

they have been happy together?

Lafont: No, she’s not happy with him, either.

The only common thing between them is that they are the same age,

and maybe have the same problems and the same questions, but not the same

answers. It’s for this reason that it’s impossible to continue.

Everything explodes because nobody can understand the other.

BD: There’s no communication?

Lafont: No communication. For Golaud, the

only communication he finds is in brutality and physical strength. At

the end, he begs Mélisande to forgive him.

BD: Does she forgive him?

Lafont: I think so. He’s a profoundly

good man with a past. He knows a lot of things, and maybe he knew

a lot of pain. He is marked by his destiny, but he is not a beast.

Very often in productions, Golaud is a beast with big muscles.

No! He cries very strongly.

BD: Is it right that he killed Pelléas?

Lafont: Yes! There are a lot of reasons

to kill, and he doesn’t want to kill him, but he becomes mad. He doesn’t

know what to do and, of course, it’s terrible to kill.

BD: Today he would plead temporary insanity?

Lafont: I think so. But when he kills Pelléas,

for me it’s difficult to accept this idea and to express it. It’s

very difficult to show this. It’s a pity that in France a lot of

people do not like this opera.

BD: That’s too bad. We had it here last

season...

Lafont: [Laughs] What a pity, without me!

Who was in it?

BD: Jerry Hadley was Pelléas,

and the Canadian baritone Victor Braun sang Golaud. [Faith Esham and Teresa

Stratas sang Mélisande, Yvonne Minton was Geneviève,

and Dmitri Kavrakos was Arkel. James Conlon conducted,

and Frank Galati

directed.]

Lafont: In Pelléas, it’s impossible

for me to listen to singers with a strange accent, because the words

and the music are so closely knit. It’s very important to understand

every word, every comma. In Carmen, never mind. It

doesn’t matter. In Faust, it doesn’t matter. Even

in Don Quichotte, but in Pelléas it does matter. Otherwise

it’s impossible because the music is the most French, and the most delicate,

yet strong in its delicacy. It is the most French opera of them

all, and the words are very important with this music. One day

I heard Pelléas et Mélisande in a theater without

any music.

BD: Just the Maeterlinck spoken as a play???

Lafont: Yes, and it was very boring. I didn’t

like it at all.

BD: Maybe you missed the music too much.

Lafont: Yes. The music takes the words

and elevates them, and for this reason we must understand. If we

don’t understand the words, we don’t understand the music. [Demonstrates

poor then appropriate ways of singing the declamation.] The

melody is the same, but we must understand the end from the opening sentence.

We must feel something strange. If Golaud sings like an opera singer,

it will come across that he’s a strong man with a good strong voice.

BD: That is not Golaud?

Lafont: He may be Golaud, but that is not for

me. I read a lot of things about it. For example, Debussy wanted

a baritone for Pelléas, not a tenor, because he wanted to hear

the high A sounding a little bit difficult. For a tenor, this note

is normally easy, but it should not be easy for this character. Debussy

also wanted to hear the low tones round, not like Golaud’s low notes but

a little bit near. They should not be so far away. He wanted

the two voices a little bit close. For Mélisande, he said it

depends on the voice of Golaud. We must find a voice in accord with

Golaud, that matches him. I don’t like a very light soprano for Mélisande.

She should have something a little heavier and deeper in sound. My

favorite Mélisandes in my career were either mezzos or high mezzos.

The two or three sopranos I had beside me were way too light.

It was all too fragile-sounding.

BD: She should be more of a Dulcinée voice

[as in Don Quichotte]?

Lafont: Yes, Susanne Mentzer wants to sing Mélisande,

and I agree! For me, she has absolutely the right voice.

BD: The next time you are asked to sing Golaud,

you should ask for her.

Lafont: Yes, but it is not my decision.

[Laughs] I am not Pavarotti or Domingo, who decide on the rest of

the cast!

BD: But you can make a suggestion...

Lafont: I do, and very often.

* * *

* *

BD: Do you adjust your vocal technique for

the size of the house and the acoustic?

Lafont: The technique is the same for a small

house or a big house. It depends on the breath control. In

a very big house, you need enormous strength when it comes to breath

control. Chicago is a very big house, and the breath support has

to be stronger in this house. In the Met, the acoustic is not so

good, and you have to be very strong, because it’s impossible to hear

yourself.

BD: The sound goes out and doesn’t come back?

Lafont: Yes. When we sing well, very often

the sound comes back. In this house, it’s possible to hear that,

but we must sing well. I spoke about dark voices, and even a dark voice

must sing light. Listen to Samuel Ramey! He sings light.

He hasn’t a very big voice, but his voice is very projected, and when

it’s focused it cuts through like an arrow! It’s a fantastic sound.

He has very good control, and I like to sing with him. He’s a great

singer. God gave each of us a voice, and the color of this voice

depends on our personality, our body, the resonance, and all those things.

But the technique must be the same for everybody, and it’s very difficult

to find and say the words for pupils and to young singers. As teachers,

we must speak with very great delicacy, but we must tell everybody to

find the right focus of the voice, to find the right tessitura, and not

to sing with the voice of somebody else. We must sing with our own

voice, and we must find our own voice and not sing with the voice of our

favorite singer.

BD: Don’t imitate!

Lafont: Not an imitator, no, no, no! For

example, I know very well Fiorenza Cossotto with

this big incredible voice. It is tremendous, with fantastic breath

support. Sometimes she sings too loud, but it is okay. I know

a lot of mezzo sopranos who destroy their voices...

BD: ...because they’re trying to imitate her?

Lafont: Of course! It is stupid.

For example, some years ago I wanted to imitate my favorite baritone, an

American, Leonard Warren. I wanted to sing like him. My singing

teacher said to me, “If you want to go on in this

way, in one year you won’t be able to sing, because the voice will be gone.”

This job is difficult because we must be right with ourselves, and we must

find exactly what we need. We must very quickly find our way, the

right way, vocally and musically.

BD: Mentally?

Lafont: Mentally, yes, and with a very deep discipline.

I know a lot of very good singers, but without a strong discipline,

they are finished.

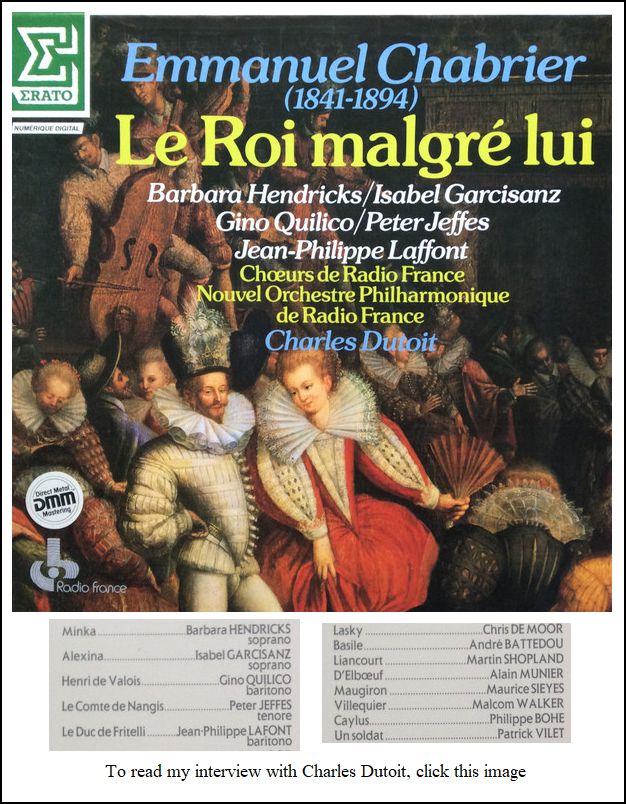

BD: Let me ask you about your recordings. Do

you sing differently for the microphone than you do on stage?

Lafont: This is a very big problem, because I

did a lot of records of operas which are not very famous, not very well

known.

BD: Such as?

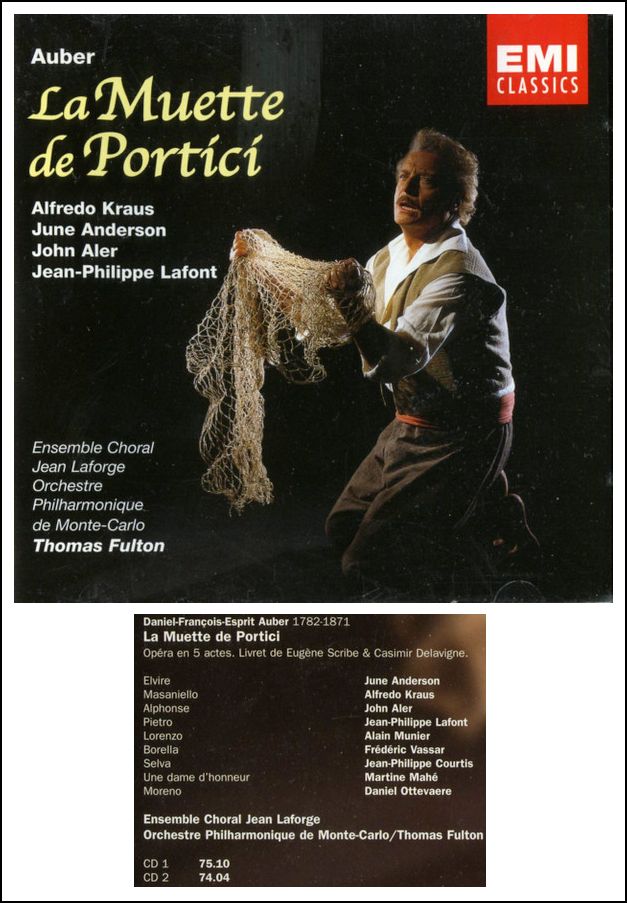

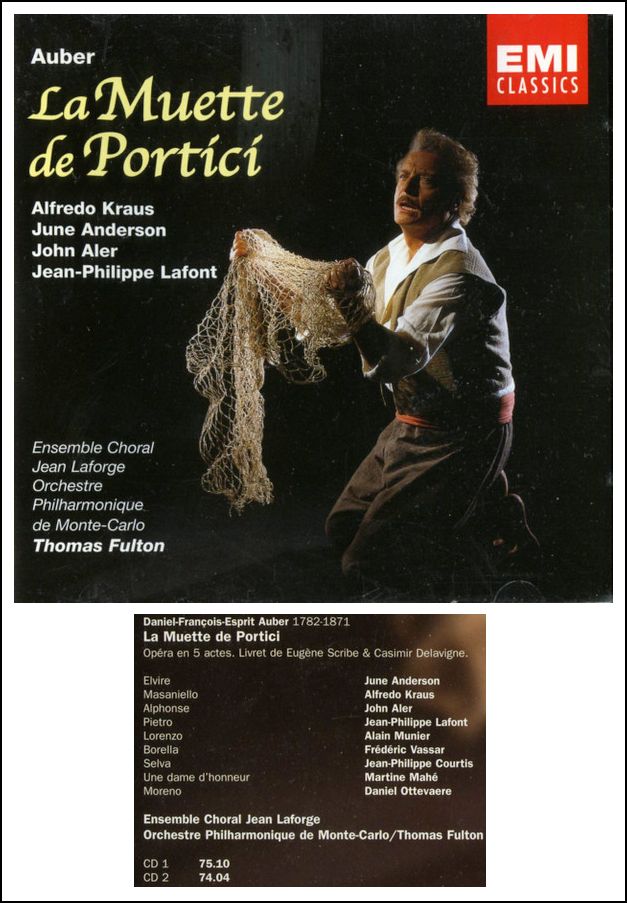

Lafont: [Thinks a moment] La Muette

de Portici. I’m sure you don’t know this opera.

BD: [With a broad smile] I have that recording!

[Having previously done interviews with Alfredo Kraus, June Anderson, and John Aler, I had obtained

most of their discs.]

Lafont: I told my manager that when I go in a theater,

everybody asks me if I had done any solo records. I have had to

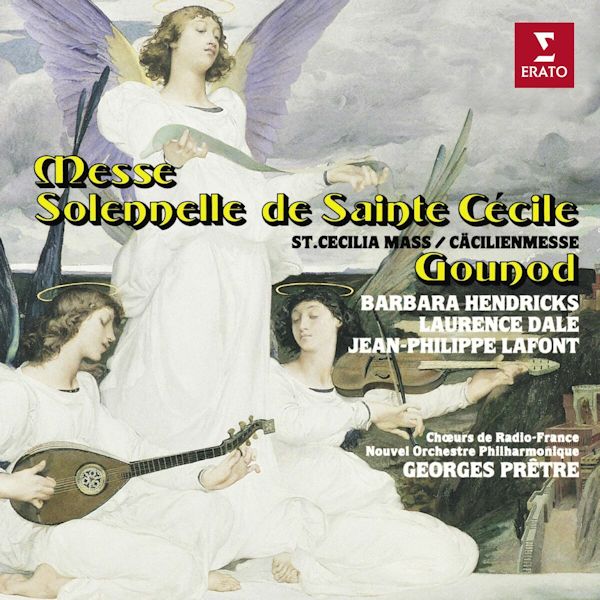

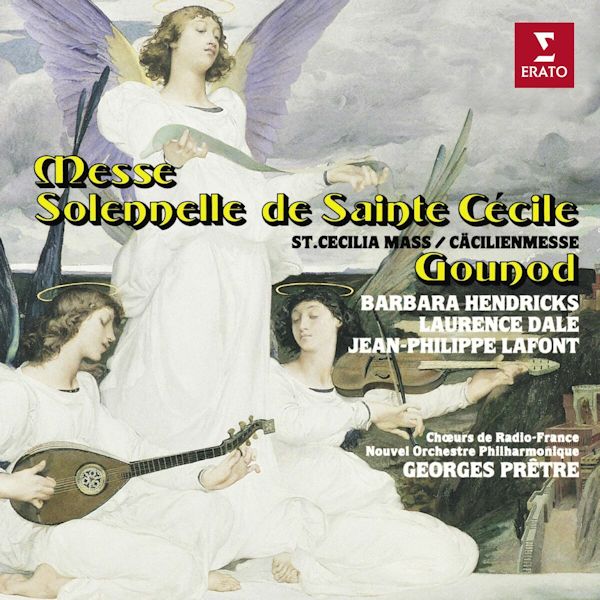

say no. I have recorded the Gounod Messe Solennelle with

Barbara Hendricks and Laurence

Dale, and a lot of things like that, but not a recital. In France

it’s not fashionable because it’s a very big problem to sell records.

BD: Will you be making more records?

Lafont: It’s really necessary. For an international

career, it’s absolutely necessary. I’m not jealous, absolutely not.

It’s very good if another baritone records. I’m happy for him,

but when I see a lot of records of Dmitri Hvorostovsky

in the music stores, I am a little bit angry. Our country is not

very interesting for artists. It was one or two centuries ago, but

our country doesn’t help us. I don’t want to

say anything more.

BD: I understand. Thank you for this conversation.

I hope you will return to Chicago.

Lafont: Thank you very much.

= = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = =

----- -----

-----

= = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = = =

= = = = = = =

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on September 30, 1993.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1996. This

transcription was made in

2026, and posted on this website at

that time. My

thanks to British soprano Una Barry for

her help in preparing this

website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted

on this website, click here.

To read my thoughts

on editing these interviews for print,

as well as a few other interesting observations,

click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was

with WNIB,

Classical 97

in Chicago from

1975 until its final moment

as a classical station in February

of 2001. His interviews

have also appeared in various magazines

and journals since 1980, and he continued

his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are

invited to visit his website for

more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews,

plus a full

list of his guests.

He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about

his grandfather,

who was

a pioneer in the automotive field more than

a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with

comments,

questions and suggestions.