|

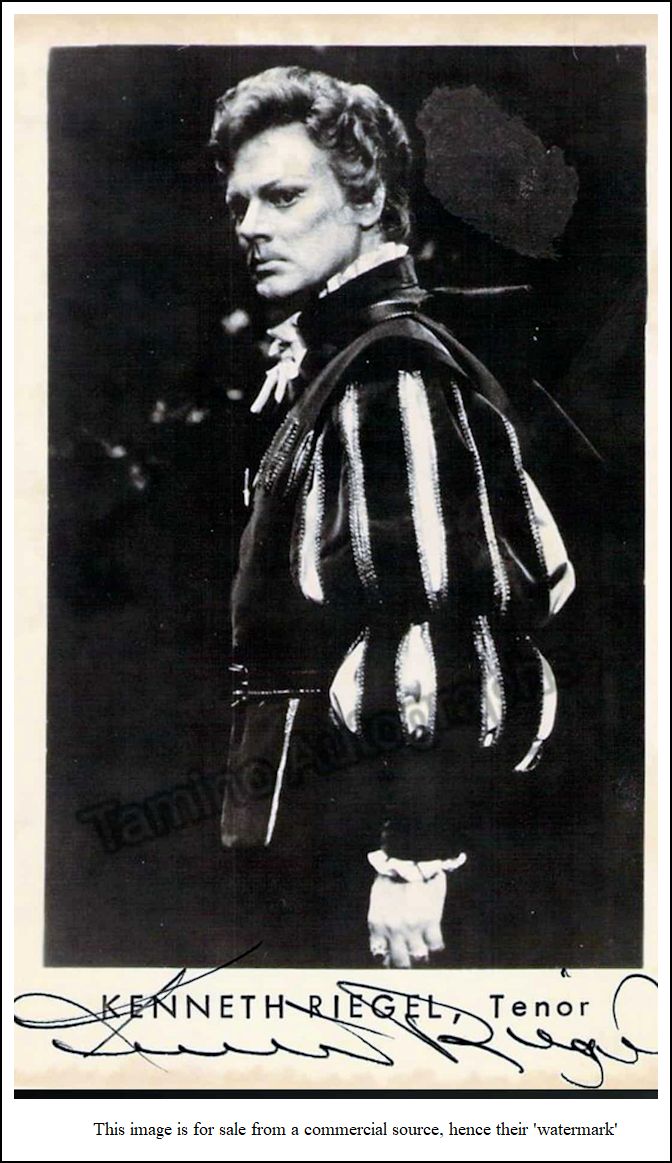

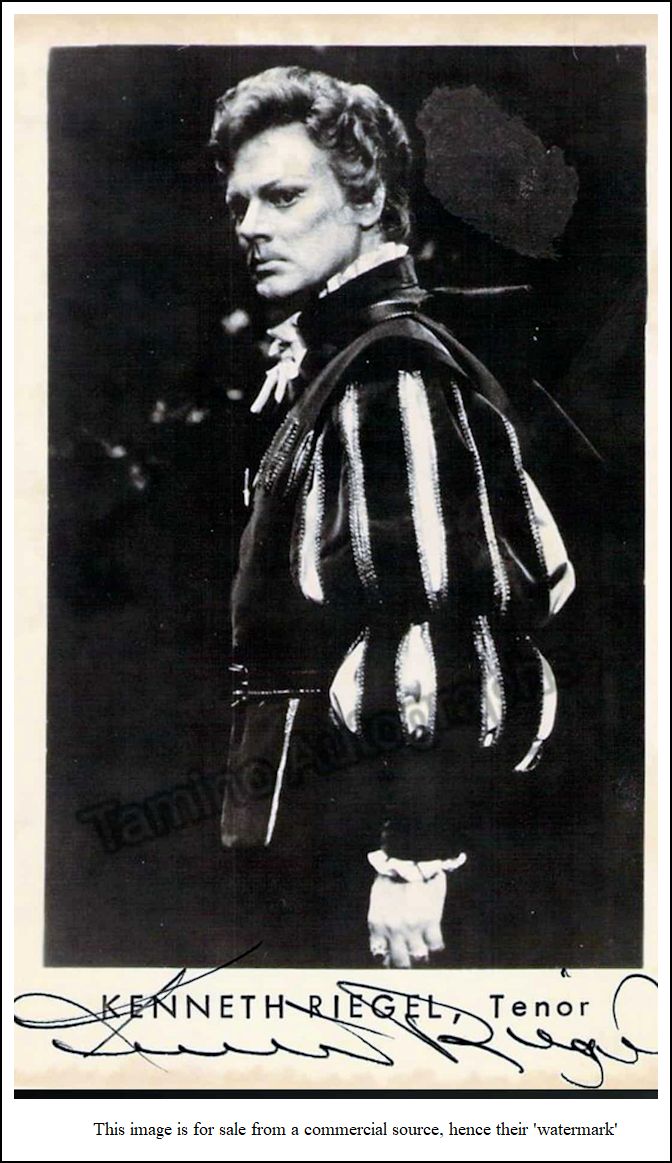

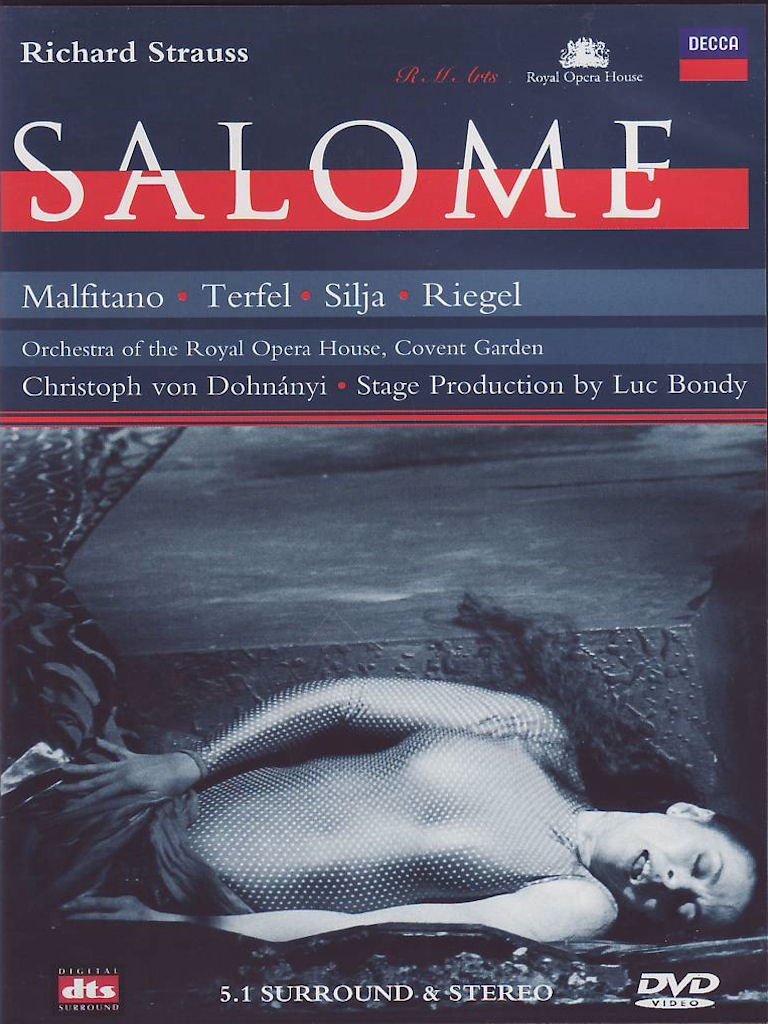

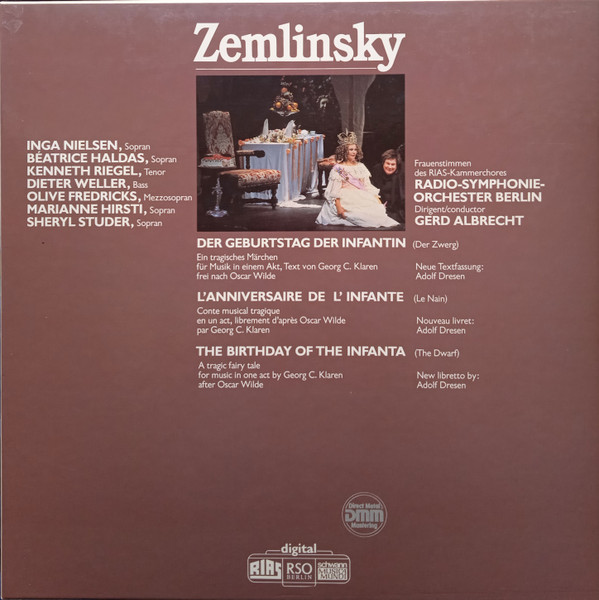

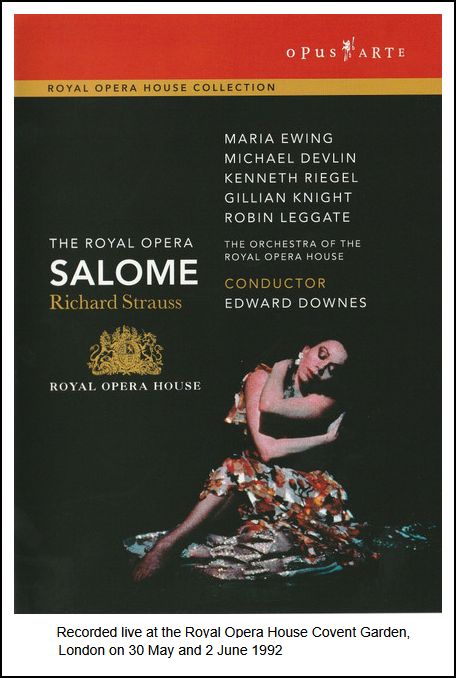

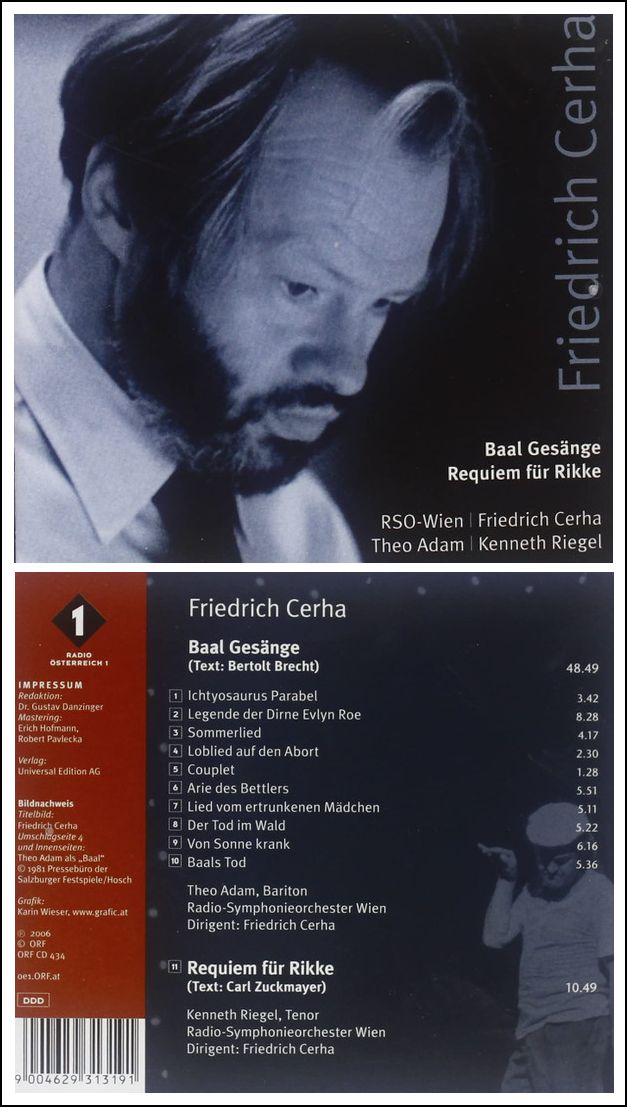

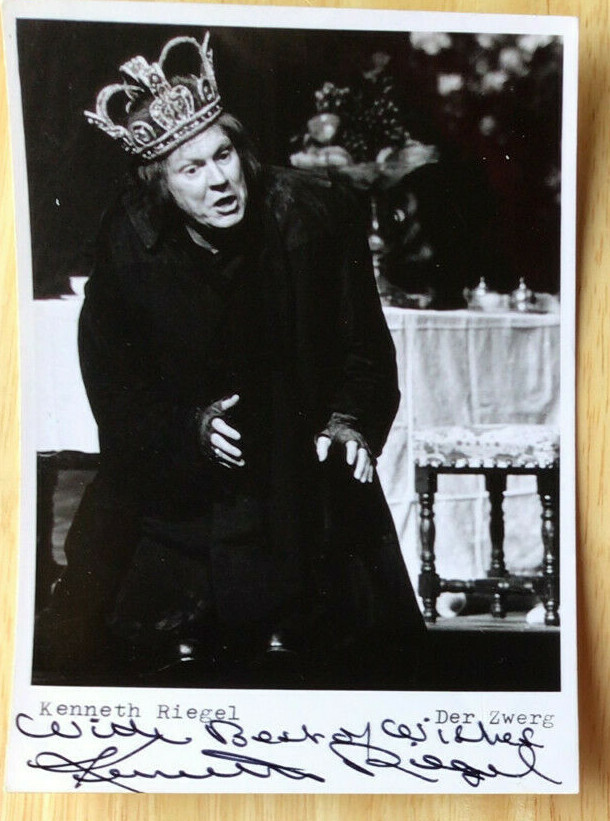

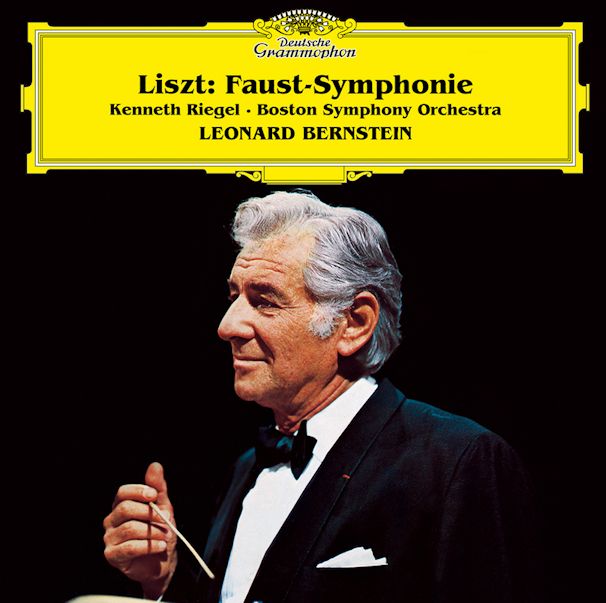

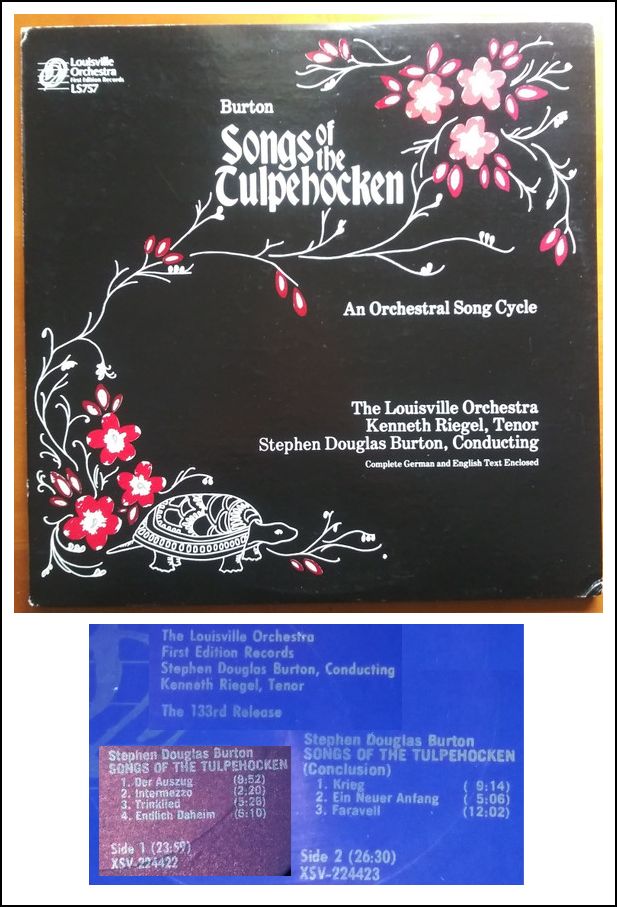

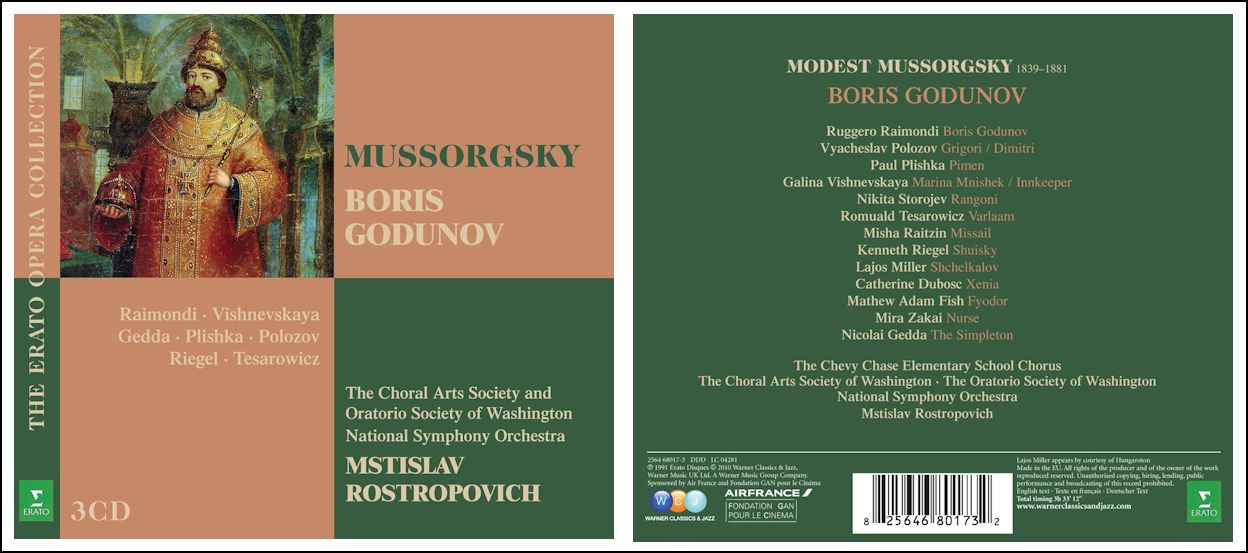

Tenor Kenneth Riegel was born on April 19, 1938, in Womelsdorf, Pennsylvania. He made his theatrical début as the Alchemist in König Hirsch [Henze] at Santa Fe Opera in 1965, debuting at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in the same year. He was engaged at the New York City Opera from 1969 to 1974. He debuted at the Metropolitan Opera in Les Troyens in 1973 (as Iopas, opposite Jon Vickers and Shirley Verrett), subsequently appearing at the Met in another 102 performances in operas including La clemenza di Tito, Les contes d'Hoffmann, Elektra, Fidelio, Lulu, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, Salome, Die Zauberflöte and Wozzeck. He made his first appearance at the Salzburg Festival in 1975. In 1979, he sang Alwa at the first performance of the 3 act version of Lulu at the Paris Opera. He played the title role in Der Zwerg [Zemlinsky] in Hamburg in 1981. In 1983, he created the role of the Leper in Saint François d'Assise [Messiaen]. Riegel died in Sarasota, Florida on June 28, 2023, at the age of

85. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 6, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1998. This transcription was made in 2026, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.