Tenor Jonathan Welch

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

[All names which are links on this webpage refer to my

interviews elsewhere on my website]

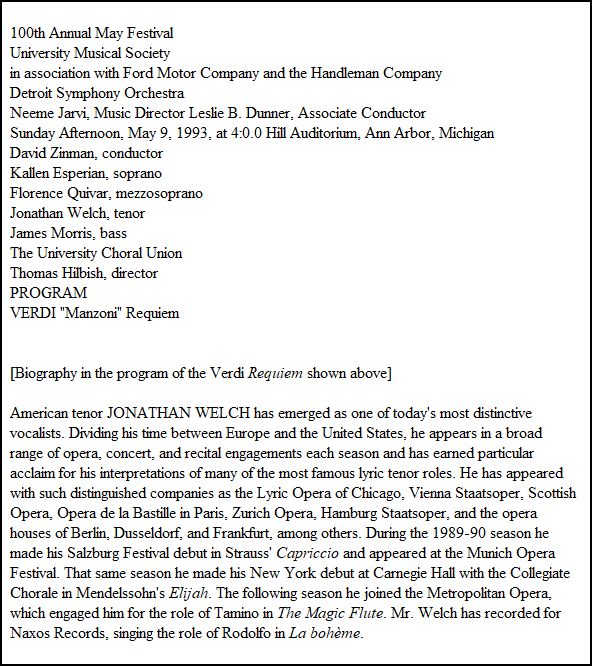

In September/October of 1989, Welch sang the Italian Tenor in Rosenkavalier

at Lyric Opera of Chicago, with Anna Tomowa-Sintow, Anne Sophie

Von Otter, Kurt Moll,

Kathleen Battle, and Julian

Patrick in principal roles, and Jean Kraft, Florindo Andreolli,

Cynthia Lawrence and Arnold Voketaitis among

the smaller parts. Jiri Kout led the production by Günther Schneider–Siemssen,

which was directed by Willy Decker. On a day off between performances,

Welch and I reunited for a conversation.

As we were setting up to record, the fact that we were old friends

produced laughter-filled banter. Full disclosure, both Jonathan

and I went to school together, at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington,

Illinois. We were a year apart, so we compared birthdates [his was

February 3], and he mentioned that he was an Aquarius (January 20 - February

18).

Bruce Duffie: Is it good for singers to be Aquarian?

Jonathan Welch: There are a lot of show-business-types

that are Aquarians, a lot of artistic people. Mozart was an Aquarian

(January 27), as was Jascha Heifetz (February 2).

BD: You were just talking a little bit about

the air quality. How much concern does the day-to-day weather, the

air quality, the temperature and everything else affect you and your performance?

Welch: I’m a pretty healthy singer, and there

aren’t a lot of things that bother me, but you can tell when the air’s

bad. It’s just an irritation in your voice, and it bothers everybody.

BD: Is there anything you can do to overcome

that?

Welch: Have a good attitude. [Laughs] I’m

serious. Some people get real crazy about their voice. They

have to have exactly so many hours of sleep, or I know what they have

to do for this or that. All of us have our routines, but some people

are just fanatical about them. I wouldn’t want to be that dependent

on always having my good luck charms, or whatever. I want to be

able to get there half-an-hour before the curtain, and when the train

is late I am still be able to go on and not be crazy.

BD: So you’re a real ‘trooper’?

Welch: That’s kind of the American way.

You know, ‘The Show Must Go On’.

I’ve done that... I got caught in a real bad rainstorm once before my

first Rigoletto, and I literally showed up a half-hour before curtain.

But I went right on, and still was passing out opening night gifts, and

laughing, and joking with everybody. That’s the way I’ve got to do

it, but I’m lucky. My voice doesn’t require a lot of fuss. It’s

just always there. It’s nothing to brag about, but it’s just how

I’m built.

BD: You say getting there half-an-hour early

is cutting it tight. When do you usually want to get to the theater?

Welch: I always like to be there at least an

hour before curtain. In most places I’ve ever been, that’s when they

want you there as far as the makeup, and costume, and all that. But

I’m not one that has to be in the theater hours before.

BD: Is it more satisfying to do leading roles

than smaller roles or supporting roles?

Welch: I don’t know exactly what you mean by

supporting roles. I think of the Italian Tenor in Rosenkavalier

as a leading role. It requires a special voice, a good voice. It’s

not what I’d consider a comprimario or a secondary role. I

don’t mind doing parts that are small in what you do. For example,

in Eugene Onegin, Lenski gets killed, but the opera’s not called

The Death of Lenski. I also do the Italian Tenor in Capriccio.

I did that in Geneva, and I arrived at the theater just before

the show started. Everybody else was already in costume and ready

to roll, and I wasn’t there an hour before the show because I don’t go

on for quite a while. But there’s a case where it’s a small role.

The Italian Tenor in Rosenkavalier is only one aria, but wow, what

an aria!

BD: You get offered a whole bunch of roles. How

do you decide which roles you’ll accept, and which roles you’ll postpone,

and which roles you’ll never do?

Welch: You have to know your own instrument. There

are some roles that people talk to me about that I think I will do eventually.

I know it’s just a matter of time, and I’m holding them at some place

in the calendar. In my case, there are several roles that I’m not

even going to look at until after I’m 40. I’m 38 now, so I’m getting

close to incorporating some of those.

BD: But you’re not going to look at them until

you’re 40, then you begin to incorporate them, and decide if you’re going

to sing them if and when you get offers.

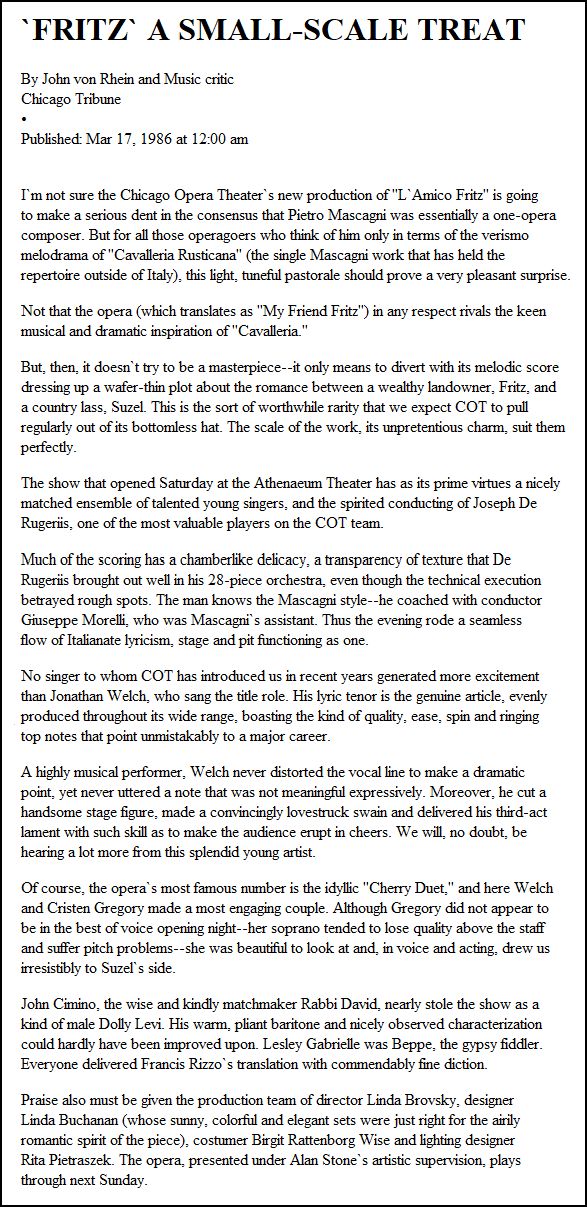

Welch: Yes. For example, I’ve been offered

several big roles such as Don Carlos. I was also offered Cavalleria

Rusticana, and I always ask why not do L’amico Fritz? It’s

a beautiful work, and is one of the most underperformed operas. [Note

that Welch sang this work with the Chicago Opera Theater in 1986. To

read an interview with the conductor and director of that production,

where they discuss the work and Welch’s

participation, click HERE.]

BD: Do you ever feel that you should be doing

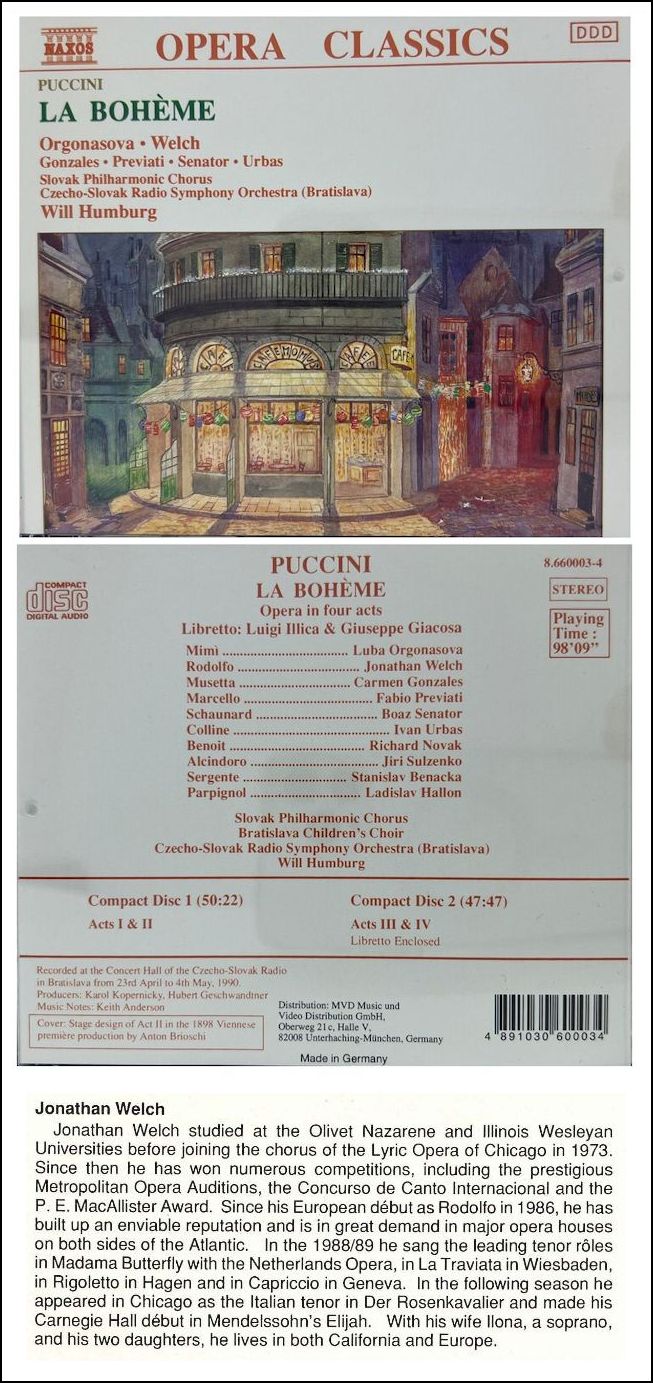

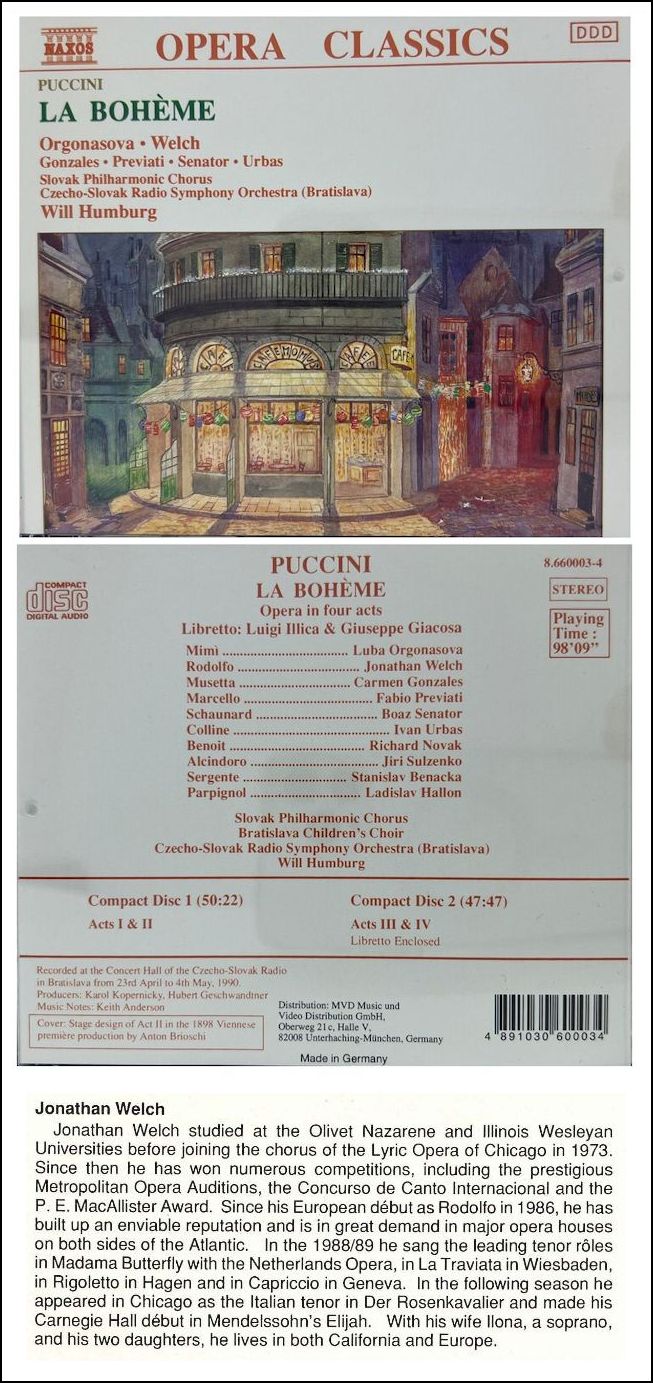

more lesser-known works, instead of always Traviata, and Bohème,

and Rigoletto?

Welch: Well, there’s the practical side of it.

Everybody knows Cavalleria, but how many people know L’amico

Fritz, yet that’s something which is perfect for me. There are

some Puccini roles that I don’t do, such as Calaf in Turandot, and

Cavaradossi in Tosca. I’ve turned down several offers for Tosca,

and there’s a case where someday I probably will do it.

BD: Is Rinuccio in Gianni Schicchi too

light for you?

Welch: No, I would do Rinuccio. I do Butterfly

now. [We come back to Pinkerton at the end of the interview.]

* * *

* *

BD: Are you at the point in your career that

you expected to be at this age, and are you doing the roles you want to

do?

Welch: Yes, absolutely. I’m really hungry

to do Manon. I’ve done Werther, and I really love

that. I also want to do Romeo, and I’d like to do Faust

as soon as I can, and Lucia. Those are big right now for

me, and I’m waiting and hoping the next time an opera company calls,

they offer me one of them. I had a chance to do eight performances

of Faust in Rome, but it was one of those times where everything

comes at once, and then you have the period where nothing happens.

I couldn’t do them, and it was a big disappointment. But it will

come.

BD: What are some of the operas that you’re doing

now that please you?

Welch: Now I’m doing Traviata, Rigoletto,

Werther, Bohème, Butterfly. Also, Eugene

Onegin is coming up for me this season.

BD: It’s a nice balance. There’s a French

opera, some Italian, and a Russian.

Welch: Right, and Mozart. I have done

already Clemenza di Tito, and I’m doing Die Zauberflöte.

I’d like to do Don Giovanni. It surprises me that some people

say they don’t think of me as doing Don Ottavio, but I think it would

be fun to do him with some fire.

BD: While you’re here in Chicago, they’re doing

Clemenza de Tito [with Carol Vaness, Tatiana Troyanos/Suzanne Mentzer, Susan Graham, Susan Foster,

Gösta Winbergh,

and Mark S. Doss, led

by Andrew Davis, and

directed by François

Rochaix]. Do you make sure that the management of Lyric Opera

knows that it’s in your repertoire?

Welch: Actually, I haven’t mentioned it to Ms. Krainik. I went

to the dress rehearsal the other day and enjoyed hearing the other people

sing it.

BD: I just wondered if it’s partly your responsibility

to make sure that managements know as much about you as they can.

Welch: They have your repertoire sheet and all

your biographical material, for sure. I’ve told some Intendants

that whenever they’re thinking about doing Manon or Lucia to

let me know. I had a chance to do Manon with Welsh National

Opera, but I couldn’t do all the performances, and they were going to

have to split it up among other tenors. They would rather go with

one person, so there was a case where that production fell out. That

happens sometimes. You hate it when it’s one that you really wanted

to do, but it’s the same in any business.

BD: As long as you get enough good opportunities,

then it’s fine?

Welch: Oh, yes.

BD: Is singing fun?

Welch: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely.

BD: When did you first decide you wanted to be a

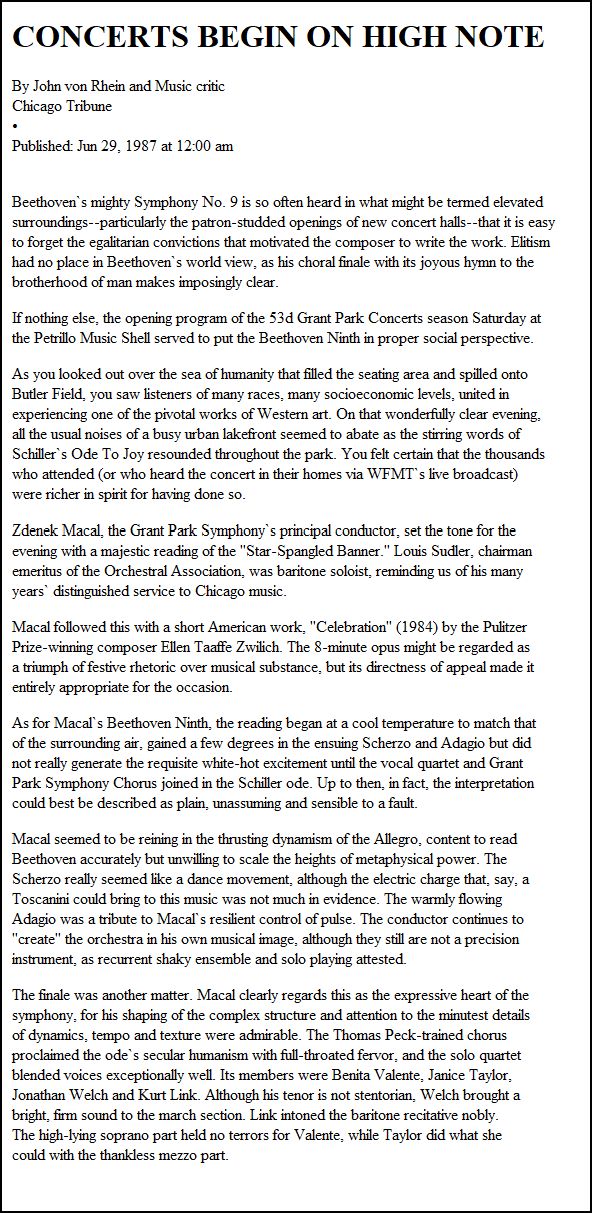

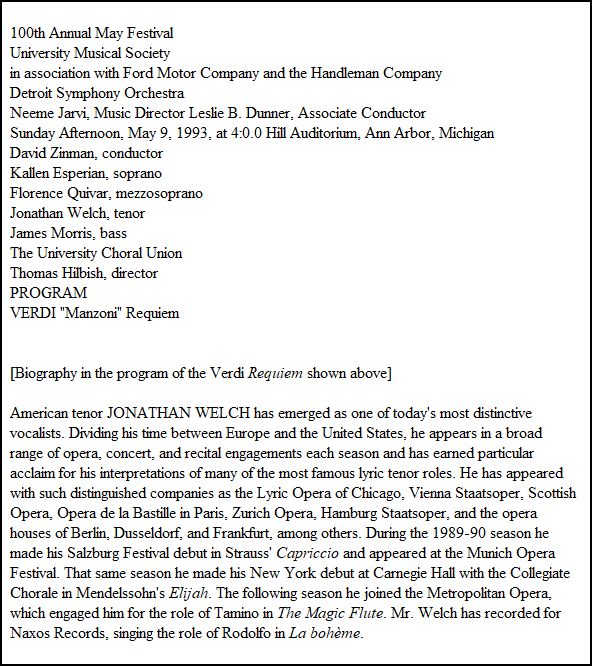

singer? [Vis-à-vis the review shown at left, see my interviews

with Zdenek Macal, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich,

Benita Valente, and

Janice Taylor.]

Welch: It’s really funny. I never really

thought of it as deciding I wanted to be a singer, because it was almost

like acknowledging the fact that you have a certain color hair or eyes.

I just always accepted it as a fact that I am a singer. When

I decided to pursue it professionally, I wanted to be an actor. I

was in community theater, and the musical extent for me in my dreams and

my fantasies as a young boy was to be a Broadway-type singer. I

wanted to be a legitimate actor. I was in drama club and community

theater doing all kinds of plays and musical comedy. But the Broadway

musical stage isn’t now like it was back in the heyday of Rodgers and

Hammerstein. That still wasn’t such a great era for tenors, but more

for baritones. You had your comic tenors, such as Marcellus Washburn

in The Music Man, etc. In fact, when I was 18 I was all prepared

to go to Illinois Wesleyan as a drama major, when a voice teacher and

good friend of our family in Danville said I should major in music, and

consider opera. That would give me a chance to act and sing.

BD: Now you’re heading to the Vienna State Opera

in this coming season.

Welch: Yes. I’m going to do Bohème,

Butterfly, Traviata, and Rosenkavalier. It’s

all the good stuff.

BD: Do you sing differently in different size

houses?

Welch: No, I don’t sing any differently.

BD: No change in technique, whatsoever?

Welch: No.

BD: Do you prefer singing in a large house or

a small house?

Welch: That doesn’t really make any difference to

me, because you have the energy of the people, the audience, and you

feel that whether it’s a large house or a small house. When the

energy’s there, that’s just something which is in the air. It’s

not always that you can see into the crowd, especially depending on how

something is lit. Sometimes the lights are so bright that you don’t

see very far into the house at all. You’ve got that contact with the

conductor and the orchestra, but as far as how big the hall is, no, I don’t

sing any different. I sing in all size houses. I sang a concert

in the Met when I won the Met Finals, and that’s 4,000 plus standing room.

Visually, that’s really something. It can be a little intimidating

sometimes just because a house is so beautiful. I don’t know if ‘intimidating’

is the right word, but you feel it, and you really experience it. I

enjoy some of the beautiful architecture, and the baroque architecture in

what we call ‘jewel box’ houses

in Europe. I like those, and that’s fun. There is a difference

as far as how you feel emotionally, vis-à-vis the contact with the

audience, but as far as singing a role with more oomph, no. Fortunately,

the bigger houses that I sing in, like the Lyric, are wonderful acoustically,

so you don’t have to change the voice at all. The pure quality of

the voice is there. It just depends on the acoustics of the house

for it to cut through.

* * *

* *

BD: You’re continuing to make a career in Europe.

Is this the advice you give to younger singers, to go to Europe to

make their career?

Welch: Not necessarily. There are as many different

ways to make a career as there are people. That’s what I’ve always

said, and that’s what was always told to me. I can just say that

it was a good thing for me to do. It was important for me to talk

to people who were mentors for me, and I respected their opinions.

Anna Moffo was one of

those people, Risë

Stevens was another, and also Carol Neblett. These people were

all judges in the Met competition at various levels, and Risë was

then the Director of the Metropolitan Opera National Council. They

basically were my stage mothers, and certainly all of them brought a wealth

of experience, and they all thought that it would be a really good thing

for me to go over there. They were sure I wouldn’t have to go and

sing everything in German translation, and that was the case with the exception

of one role. Everything else that I’ve done over there, I’ve done

in original languages. In fact, when we negotiated my contract, we

had it written right in that I would sing only original languages. When

you’re a tenor, you can get away with some things like that, but actually

it was very good for my home house.

BD: Are tenors in such short supply that you

can dictate terms?

Welch: Let’s just say I didn’t have any

problem getting that stipulation in my contract, and I’m really glad.

Many of my colleagues were also glad, because by my being able to do things

in the original language, they all got to do them in the original language.

The point being, I think that it’s okay for a young person to go over.

In fact, this was specifically one of the things Risë Stevens

and I talked about. She said that she did roles in German that you

want to eventually get into the original language, but she said I was

young enough that it didn’t matter. It was okay to know it in German

first. In my case, I started a little later, and because

I was a little older, I was more interested in doing these things in the

original languages. That way I could immediately guest in any house

in the world where they did standard repertoire in original languages.

Before I agreed to come to Europe, to my specific home house in Wiesbaden,

and make a major move in my life with my wife and children, I said I wanted

some assurances, and I was able to get them. Of course, everybody

can’t do that. But by and large for young singers, if you’re smart

and you know what’s right for you vocally, and have the courage to say no

when you know something isn’t right for you, you can go over there and do

just fine. Some people have heard horror stories of how they made people

sing out of their fach [vocal category], and do certain things that

they shouldn’t do. They were afraid, because if they didn’t do it,

then they’d hire someone else to do it. Well, that’s silly. You

can’t do what’s wrong for you just to get a job, or keep a job.

I’ve said no a lot, and not in a prima donna way, but when it’s just wrong.

Then, even though they’re disappointed, they’ve all said I was a very

intelligent singer.

BD: Does that gives you more credibility and more

respect?

Welch: Absolutely. It’s worked, but also

there’s something to be said for being a good colleague. When you’re

easy to get along with, and you’re cooperative, when you get down to real

issues that you really need to take a stand on, and say no, and assert

yourself, then maybe people take it a little better. I’m not so temperamental.

I usually only make a fuss if it’s something that’s really important, and

they respect it.

BD: Is there a competition amongst tenors for roles,

or rosters, or work?

Welch: There’s always good, healthy competition.

The Germans have this fach system, which is like being in

a pigeonhole. Every voice is a type, and I’ve often said that we’re

not model-numbers of Mercedes-Benz. There are some general voice

classifications, but someone may go a few notes higher than someone

else, and someone might go a little lower and have certain strengths in

other areas. So it’s a good guideline, but don’t try to put me in

a fach. The only competition is that some houses do more

lighter repertoire one year, and heavier things another year. These

are mostly repertory companies, so they’ve got a house full of singers,

and a lot of them have a ballet company, and a drama company, so they’re

regular performing arts factories. My particular house in Wiesbaden

is a staatstheater [state theater], and there are over 300 people

that come to work there every day. We have our own cobblers, and our

own wig makers, and costume makers. These people work there year-round,

and have pension programs. It’s an incredible business.

BD: Now, you’re leaving Wiesbaden to go to Vienna?

Welch: I am finishing my last year in a fest

contract in Wiesbaden [which means a stable or fixed contract, as opposed

to a freelance artist who sings as a guest in the house]. I’m

guesting all around Europe, and in the States, too. The year that

I go to Vienna will be my second year that I’ll be free from my home house

in Wiesbaden, and I may decide to have a home house somewhere else. I

don’t know if he’s still there, but for many years Zurich has been the home

house for Francisco Araiza.

Having a home house is a totally different situation. If you’re

sick, or something happens and you can’t sing, you’re still paid your salary.

We have nothing like that in America. It’s a totally different system.

BD: Should we have that arrangement here?

Welch: I don’t think there’s a big enough market

for us to do it over here. Plus, over there, they’re subsidized

by the government. So much of their tax money goes for the performing

arts. But back to your question about competition, a house will

have only so many roles in certain fach that they’re going to hand

out. If you’re a lyric tenor, and they’re planning a dramatic role,

you don’t want it. It’s not a matter of competition, but rather

a matter of doing what’s intelligent for you.

* * *

* *

BD: You were talking a bit about doing things in the

original language. Do you like this idea of having the supertitles

above the proscenium?

Welch: Yes, I do, because it opens it up for

more people.

BD: Is opera for everyone?

Welch: It can be. It’s like a lot of things.

You never know until you try them. That’s that way with anything

in life. I discovered the joys of cross-country skiing when I was

well into my 30s. I learned an entire new language when I was over

35. Perhaps it would be more true to say you like what you know.

If they have a chance to experience opera, then it would be another story,

and that’s where the key to building audiences will be for us. Reaching

out and trying to get more people from the general populace should begin

in the schools. Educating our children, and developing an appetite

is the future of opera in America.

BD: Is the industry of recordings, and television,

and videotape helping or hindering?

Welch: I think it’s helping all the people who

never would think of buying tickets and going to the opera. Their

only idea of the opera is maybe the Marx Brothers film Night at the Opera,

or seeing Three Stooges lip synching the Lucia sextet. Goodness

knows people have preconceived ideas about opera, often just because of

spoofs they’ve seen. Now with all of the broadcasts live from the

Met and everywhere, it comes into people’s homes. Even if they see

some of it by accident, they might want to listen to some of it. They’re

watching the program, and the subtitles are down there on the screen.

If they showed a foreign film, you would want the subtitles. That

way they can understand much of it. A lot of my children’s

early experiences with opera was watching it on television. They

could read the lines and know what was going on, and they really got the

bug. So I think there’s a much better chance with more and more opera

being telecast, and showing up on videos.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of opera?

Welch: Sure, I am. Yes, very much so.

BD: How are you dividing your career now between opera

and concert?

Welch: I tried to do a mix. I had an experience

with Herbert von Karajan last summer. I was privileged to do an

audition for him and to meet him. Now he’s passed away, but a friend

of his came to a performance of Traviata that I did, and told him

about me. They wanted a cassette, which I sent them, and he said he

wanted to hear me. So, they flew me to Salzburg, and when I sang for

him, he said I should do concert and oratorio work, not just opera. He

said that I had many colors in my voice. This was like an echo from

the past, because I’ve done master classes with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf,

and she always told me the same thing. We would work on songs, as

well as arias, and she said I could do it all. So I try to keep a good

mix. It’s important. It gives you a lot more variety. What

I do on the concert stage enhances what I do on the opera stage, and vice

versa. Variety is the spice of life, and I would get very bored if

I just did one thing. But I always remember it’s not just to do

something else. It’s always got to be the right thing, and sometimes

that’s based on a lot of things, not necessarily just repertoire. Vienna

wanted me for Maria Stuarda. I looked at the part, and it would

certainly be okay for me, but I have never done this role, and they wanted

me to come in with just a couple days’ rehearsal. So, I spoke to my

management. I like to sing in Vienna, and I’m flattered that they

offered it to me. They even picked the right repertoire, but they

didn’t pick the right situation in which to present it, so I turned it down,

and they respected my decision.

BD: Does the singer have any real influence as to what

operas are being done? Can you have an impact on the repertoire?

Welch: If you’re a world star, and they want

you for practically any production, then you can say you want to do this or

that. But other than that, I don’t know how much we specifically influence

what gets done.

BD: Do you yourself believe in expanding the

repertoire?

Welch: Yes. When you’re speaking about

America though, money is the bottom line. You’ve got to be able to reach

the market, and you have to consider the marketplace. There are

certain places when they know what the traffic will bear, and you’ve got

to have a real mix of styles and periods of whatever you’re doing to reach

the different corners of that marketplace so that you can survive.

BD: Do you feel that you, with what you can provide

vocally, are a commodity?

Welch: Sure, you’re a commodity.

BD: Should you be traded on the stock exchange?

Welch: Hopefully not today, since it’s Friday

the 13th. [Much laughter]

BD: Should we trade vocal futures?

Welch: Oh man, this is getting surreal...

* * *

* *

BD: Let’s go back to repertoire. Tell me about

the Duke. What’s he like?

Welch: What a rascal the Duke is. What a rotten

guy.

BD: Do you like playing rotten guys?

Welch: You reach down inside yourself to find

what may be rotten, or what lies within you. It may not be that

you’re a wanton womanizer, but you try to find something that you can identify

with. The Duke doesn’t quite bother me as much as a role like Werther.

That’s one which was really hard. But the Duke just goes roughshod

through these women. He’s in love with the idea of being in love.

When he sings Parmi veder le lagrime [I seem to see tears...], for

a moment he believes that he feels sorry for this poor Gilda. But

then the minute he finds out that they’ve got her in his chamber, he goes

back into his old lecherous self. I don’t know if there’s a redemptive

bone in this man’s body.

BD: In this or any other character, how deeply

can you dig into the psyche of the person you portray?

Welch: It’s good to do your homework as much as

you can. You need to do a certain amount of that deep digging even

before you go into rehearsal. It gives you more dimension and depth

in the characterization if you read everything that you can. However,

I have also experienced that you can only go as far as you can and still

handle musically what the composer wanted. For example, if I let

myself go as far in Bohème as my body would want to go, and

if I totally let myself go into that sad, distraught emotion in the last

act with Mimì, I wouldn’t be able to sing. I’ve experienced

that sometimes in rehearsals where literally I got choked up and would

begin to cry. If I don’t have to sing the next day, I’ll really

let myself go, and just let the tears come, and let myself get choked up,

and just let my throat constrict. But God help you if you do that

in the first act. In Bohème it wouldn’t be appropriate,

but someplace early in another opera. You have to be careful. Your

body reacts physically to certain emotions, and that can affect your voice.

So you’ve got to find a way to project that, and still have that

beautiful, nice legato line.

BD: So, are you portraying the character or

do you actually become the character for those two or three hours on

stage?

Welch: If you dare, it’s a much better flight

to just let yourself be that character. It’s a lot more fun, and

it’s a lot more interesting for the audience.

BD: Is it a lot more dangerous? [Vis-à-vis

the item shown at left, see my interviews with Neeme Järvi, David Zinman, and Florence Quivar.]

Welch: Yes, sure it is. It’s dangerous to let

yourself get too much into the character, and in the case of Otello, it

is more dangerous for Desdemona. [Laughs] But, oh gosh, it’s

a lot more fun. For Werther, I did a lot of really serious soul

searching. When he says, "Why do we tremble at the idea of our own

death? Then he begins to toy around with the pistol, and he says,

“One raises the curtain and steps to the other side.”

I just get goosebumps now talking about it. That’s one specific

instance where you let yourself get into it, and when I leave the theater,

I feel like I really earned my money that night.

BD: Talking about Werther, should they show

the shot in full view of the audience or should it be off stage?

Welch: That was one of the things that I

talked to the director about. I worked with a German director who

is a very prominent theater director in Germany, and has many successes,

but he’s also very controversial. I told him, “I’m

not sticking anything up to my head that’s going to make a loud bang.”

He said he wouldn’t want me to do that. I remember a Tosca

a few years ago, when I was a kid in the chorus at Lyric. When the

soldiers fired, the guy who brought down the sword to signal the shot got

his hand in front of one of the muskets with these explosive charges. I

saw the man standing there with his hand bleeding. So stage weapons

that go boom scare me. For the Werther, I had to move off behind

this little building. So, people don’t actually see me pull the trigger,

but they know what I’m going to do. I have a gun in my hand, and

then there’s a shot from off stage right near where I am. In the

meantime, there’s about 25 seconds of music, and they did a real makeup

job on me. There’s a lot of blood in this production, and in fact,

some people were bothered by it.

BD: Does it have to be so very realistic?

Welch: Not necessarily. It’s a matter of choice.

Look at what is done in movies. Could you imagine Sam Peckinpah

directing Werther? People in the audience would be splattered.

The opera is based on the Goethe book The Sorrows of Young Werther.

This guy actually did shoot himself in the head, and he lived for

something like 12 hours or more after he did this, with the musket ball

in his head.

BD: So he had time to think about what he had

done.

Welch: You wonder how a person would react.

I have to sing a beautiful lyric line there, and we wondered if maybe

there’d be paralysis. So, we experimented with my curling one arm

under, and not having any more use of that arm. It was a fascinating

challenge to try to think of all the physical things that we could express

for this to really be true, to be realistic, and yet still have that incredible

music go along with it. It stretched me as a performer more than anything

I’ve ever done.

BD: Let us come back to Pinkerton.

Welch: Pinkerton is a real interesting challenge

because you can’t let yourself go with the idea that I’m going to play

this really bad guy. I played him like a very immature young man,

who is not aware of the fact that he’s an ‘ugly American’.

He would drape the flag in all that he does. He thinks the oriental

customs are amusing, especially when he’s got the contract that says they’re

married for hundreds of years, but with the clause that anytime he can

get out of it. He’s traveling from port to port, and thinks he is

really clever when he finds out how to get around the laws. The more

you can play it that way, the more scary and gross he becomes. The

audience sees this clot running roughshod over this little delicate oriental

flower.

BD: That heightens the tragedy.

Welch: Oh, yes. So there’s a case where you have

to not make a judgment about yourself and your character in the eyes of

anybody else but yourself, and try to be sympathetic to your character.

Whenever I sing Pinkerton, I don’t start feeling ashamed of myself

until the very end when he comes back with Kate, and then everything

is explained. Still, I don’t think the full impact of that has

hit him even then. Finally, of course, when Butterfly is dead before

him, he cries out, but I dare say that the impact isn’t until years later

in his life.

BD: Do you promote yourself in the third act?

Welch: I don’t. Actually, I did one production

in San Diego, which is a navy town. They gave me all kinds of

campaign ribbons, and one guy just picked the uniform apart. He said

that one of the ribbons was from Vietnam, and some of the others were not

appropriate. I will say it looked good with all those colors on there...

BD: Thanks for coming back to Chicago.

Welch: My pleasure. It’s great

to see you again.

========

========

========

------ ------ ------

======== ========

========

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on Friday, October 13,

1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB four days later.

This transcription was made in 2023,

and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these interviews

for print, as well as a few other interesting observations,

click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was

with WNIB,

Classical 97

in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment

as a classical station in February

of 2001. His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since 1980,

and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit

his website for

more information about his

work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of

his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information

about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions

and suggestions.