JC: I can’t buy a record of my Violin and Piano Sonata with my father

doing it! I tried to buy another record but they’re out of print and

they’re not printing any more. And a cassette is not the same quality

at all. That is a fabulous performance with Ralph Votapek, too.

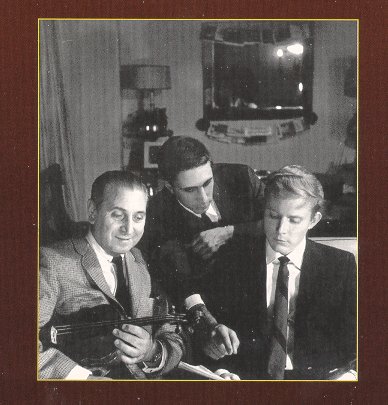

[Photo of the three of them from the CRI

CD booklet at left] It was quite wonderful. It was made

in 1966 and it’s a good record, I mean really. As far as the performance

goes, it’s much better than the Eugene Fodor one, it really is.

JC: I can’t buy a record of my Violin and Piano Sonata with my father

doing it! I tried to buy another record but they’re out of print and

they’re not printing any more. And a cassette is not the same quality

at all. That is a fabulous performance with Ralph Votapek, too.

[Photo of the three of them from the CRI

CD booklet at left] It was quite wonderful. It was made

in 1966 and it’s a good record, I mean really. As far as the performance

goes, it’s much better than the Eugene Fodor one, it really is. JC: Well, not totally. The Associate and

Assistant Conductors, Ken Jean

and Michael Morgan, will

look at some of these scores, too. But there is a real problem with

that. Last year I was on the panel of the National Endowment for the

Composer Grants, and they have had a consistent problem with policy on whether

to make the submitted scores anonymous or not. They had been anonymous

for years, and this year they started not to because they felt that many

very important composers had their stuff returned with form letters.

It was getting to be embarrassing and people were not submitting music because

it was getting to be a kind of problem. I’m not sure what the answer

is because I don’t know if it’s a good idea to be influenced by someone’s

name in the quality of the work. I’d like very much to have the work

itself tell me that it’s right. But somewhere between the two has got

to be the answer. In other words, it’s not the man’s name that should

make you do it and it’s not the quality without the name, but it’s the combination

that says this should happen or that should happen.

JC: Well, not totally. The Associate and

Assistant Conductors, Ken Jean

and Michael Morgan, will

look at some of these scores, too. But there is a real problem with

that. Last year I was on the panel of the National Endowment for the

Composer Grants, and they have had a consistent problem with policy on whether

to make the submitted scores anonymous or not. They had been anonymous

for years, and this year they started not to because they felt that many

very important composers had their stuff returned with form letters.

It was getting to be embarrassing and people were not submitting music because

it was getting to be a kind of problem. I’m not sure what the answer

is because I don’t know if it’s a good idea to be influenced by someone’s

name in the quality of the work. I’d like very much to have the work

itself tell me that it’s right. But somewhere between the two has got

to be the answer. In other words, it’s not the man’s name that should

make you do it and it’s not the quality without the name, but it’s the combination

that says this should happen or that should happen. BD: So they should live in tandem, not separately?

BD: So they should live in tandem, not separately? JC: They are intertwined and, being perfectly

honest, I think they’re inseparable. I do not have craft without conception.

When I start writing a piece and I have no ideas, I can’t harmonize the

Star Spangled Banner. I’m

so befuddled, the ideas sound so trite! When I get an idea that I

like, all of a sudden how to do it becomes apparent along with the technique.

People say that it’s either technique or inspiration. Technique is inspiration. They’re

combined; they really are. They’re inseparable.

JC: They are intertwined and, being perfectly

honest, I think they’re inseparable. I do not have craft without conception.

When I start writing a piece and I have no ideas, I can’t harmonize the

Star Spangled Banner. I’m

so befuddled, the ideas sound so trite! When I get an idea that I

like, all of a sudden how to do it becomes apparent along with the technique.

People say that it’s either technique or inspiration. Technique is inspiration. They’re

combined; they really are. They’re inseparable. JC: One is the association with the Civic Orchestra.

I’m trying to involve them with a contemporary music festival so we have

an orchestra for more twentieth century music. I reprogrammed them

this year so that every time there’s a guest composer coming —

like Karel Husa

or William Schuman

— they play a piece of his, too. I also do a lot of talking

to the Women’s Committee, and take care of many of the pre-concert lectures

that are very important, especially when you’re talking about something

like Boulez and serial

technique, which is something that people are very intimidated by.

There’s almost no analysis when you look at a serial piece, excepting to

tell you that it’s serial and that it has fleeting high strings and suddenly

an abrupt motive in the double bass or something. But they never really

guide you through it because it’s almost impossible to do. When Boulez

was here conducting, I thought it was important that we go into what this

technique is. So I tried, within forty-five minutes, to take a lay

audience through what twelve-tone technique is and then how it developed

as serial technique, and what they did have to concentrate on and what they

didn’t. They had to have no bad feelings or no inferiority complex

about the fact that they could not understand certain things because they

couldn’t be heard by the ear. That alone was such an enormous relief

to some people who were so intimidated by the fact that they couldn’t hear

it, but they thought everybody else did. That let them listen to the

piece and appreciate it, instead of getting this terrible feeling of cringing

through the whole thing and feeling inferior. So I think there are

a lot of ways that we can help.

JC: One is the association with the Civic Orchestra.

I’m trying to involve them with a contemporary music festival so we have

an orchestra for more twentieth century music. I reprogrammed them

this year so that every time there’s a guest composer coming —

like Karel Husa

or William Schuman

— they play a piece of his, too. I also do a lot of talking

to the Women’s Committee, and take care of many of the pre-concert lectures

that are very important, especially when you’re talking about something

like Boulez and serial

technique, which is something that people are very intimidated by.

There’s almost no analysis when you look at a serial piece, excepting to

tell you that it’s serial and that it has fleeting high strings and suddenly

an abrupt motive in the double bass or something. But they never really

guide you through it because it’s almost impossible to do. When Boulez

was here conducting, I thought it was important that we go into what this

technique is. So I tried, within forty-five minutes, to take a lay

audience through what twelve-tone technique is and then how it developed

as serial technique, and what they did have to concentrate on and what they

didn’t. They had to have no bad feelings or no inferiority complex

about the fact that they could not understand certain things because they

couldn’t be heard by the ear. That alone was such an enormous relief

to some people who were so intimidated by the fact that they couldn’t hear

it, but they thought everybody else did. That let them listen to the

piece and appreciate it, instead of getting this terrible feeling of cringing

through the whole thing and feeling inferior. So I think there are

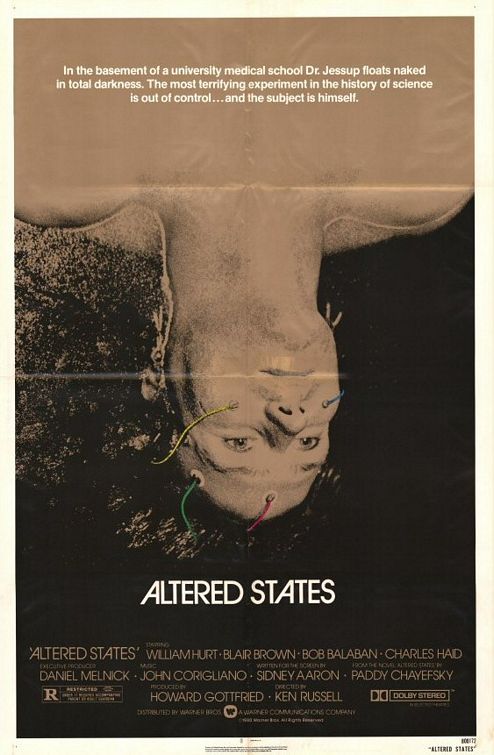

a lot of ways that we can help.  JC: Not for a while because I don’t want to right

now, but I will, probably. But I’m going to audition directors, I really

am. Ken Russell was very good because even when he changed the music,

he changed it in a musical way. Hugh Hudson tried hard, but the problem

there was that Pinewood Studios in London has a bunch of sound mixers that

not only no regard for music, but basically are only interested in sound

effects, and music as a kind of minor sound effect. They have no thought

whatsoever of line or drama, and frankly I wouldn’t do anything in that studio

again. I’d never go and do a British film with Pinewood Studios, and

they’re the biggest studio in London. And besides that, I think we

have the best players in the world in the United States as instrumentalists.

When we did Altered States in Los

Angeles, the quality of the orchestral playing was so staggering that you

could not go to any other country and get anybody to play as well. In

addition to that, I would be very careful about a director, and know that

he trusted me enough to know that I was doing the best thing for him, too.

I was going to help the director in both cases get a better result, but there’s

an element of trust directors are not used to having, because they’re used

to being the head of a ship, and there’s forty million dollars invested

in the ship. They’re afraid of trusting anyone around them because

they might be misled. There’s a lot of suspicion and a lot of crazy

tension. It’s very hard for them because they’re scared. They’re

running scared, usually. By the time a composer gets involved in a

film, they’ve spent most of the money, so the budget’s down. The company

is sitting on them for product. They are being judged by the company

executives as to whether they’re going to put promotional money in back of

this film. There’s a tremendous amount of tension in that! We’re

talking about so many millions of dollars that it’s colossal! That

amount of high emotional content is staggering, so they can’t afford to

do anything else.

JC: Not for a while because I don’t want to right

now, but I will, probably. But I’m going to audition directors, I really

am. Ken Russell was very good because even when he changed the music,

he changed it in a musical way. Hugh Hudson tried hard, but the problem

there was that Pinewood Studios in London has a bunch of sound mixers that

not only no regard for music, but basically are only interested in sound

effects, and music as a kind of minor sound effect. They have no thought

whatsoever of line or drama, and frankly I wouldn’t do anything in that studio

again. I’d never go and do a British film with Pinewood Studios, and

they’re the biggest studio in London. And besides that, I think we

have the best players in the world in the United States as instrumentalists.

When we did Altered States in Los

Angeles, the quality of the orchestral playing was so staggering that you

could not go to any other country and get anybody to play as well. In

addition to that, I would be very careful about a director, and know that

he trusted me enough to know that I was doing the best thing for him, too.

I was going to help the director in both cases get a better result, but there’s

an element of trust directors are not used to having, because they’re used

to being the head of a ship, and there’s forty million dollars invested

in the ship. They’re afraid of trusting anyone around them because

they might be misled. There’s a lot of suspicion and a lot of crazy

tension. It’s very hard for them because they’re scared. They’re

running scared, usually. By the time a composer gets involved in a

film, they’ve spent most of the money, so the budget’s down. The company

is sitting on them for product. They are being judged by the company

executives as to whether they’re going to put promotional money in back of

this film. There’s a tremendous amount of tension in that! We’re

talking about so many millions of dollars that it’s colossal! That

amount of high emotional content is staggering, so they can’t afford to

do anything else. JC: Absolutely! The thing that’s interesting

about Carlos — I think he’s really an amazing conductor. He’s one of

the great ones. He understands everything about my music; he studied

it and knows every note of it, so when a rehearsal happens I barely have

to say anything. I really don’t have to say anything because he catches

everything. And his instincts are so good! I’m just totally

in awe of him. I think he’s a major, world-class conductor, and I

think the orchestra’s amazing, too! They only saw the music yesterday,

and it’s a terribly difficult piece! They’re playing it like they

own it.

JC: Absolutely! The thing that’s interesting

about Carlos — I think he’s really an amazing conductor. He’s one of

the great ones. He understands everything about my music; he studied

it and knows every note of it, so when a rehearsal happens I barely have

to say anything. I really don’t have to say anything because he catches

everything. And his instincts are so good! I’m just totally

in awe of him. I think he’s a major, world-class conductor, and I

think the orchestra’s amazing, too! They only saw the music yesterday,

and it’s a terribly difficult piece! They’re playing it like they

own it. JC: No. What’s changed my view of concert

music a little bit has nothing to do with me, but the idea that the world

of recordings — and so much of the world of concert

music — has sloughed off from the rest of the world

so completely, and become almost a non-field. Sony barely releases

any classical music; BMG cut its label completely. They may be trying

to resurrect it, but I don’t really think it will happen. There are

no labels for classical anymore, except maybe for

the small labels that only produce records out of devotion. But all

the economic ones have ceased. I think that we have to look at this

and not totally dismiss it. There are reasons on all sides why this

happened.

JC: No. What’s changed my view of concert

music a little bit has nothing to do with me, but the idea that the world

of recordings — and so much of the world of concert

music — has sloughed off from the rest of the world

so completely, and become almost a non-field. Sony barely releases

any classical music; BMG cut its label completely. They may be trying

to resurrect it, but I don’t really think it will happen. There are

no labels for classical anymore, except maybe for

the small labels that only produce records out of devotion. But all

the economic ones have ceased. I think that we have to look at this

and not totally dismiss it. There are reasons on all sides why this

happened. BD: So you returned the money and dropped the

idea?

BD: So you returned the money and dropped the

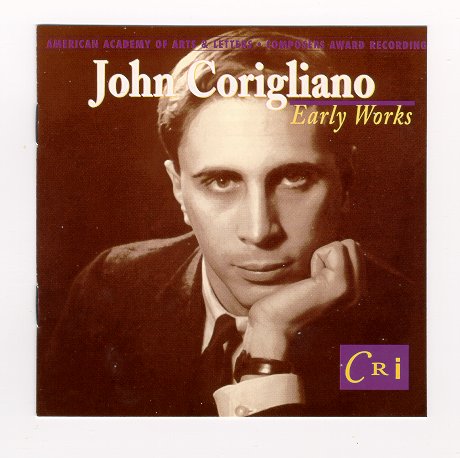

idea?| The American composer John Corigliano

continues to add to one of the richest, most unusual, and most widely celebrated

bodies of work any composer has created over the last forty years. Corigliano's

scores, now numbering over one hundred, have won him the Pulitzer Prize,

the Grawemeyer Award, three Grammy Awards, and an Academy Award ("Oscar")

and have been performed and recorded by many of the most prominent orchestras,

soloists, and chamber musicians in the world. Attentive listening to this

music reveals an unconfined imagination, one which has taken traditional

notions like "symphony" or "concerto" and redefined them in a uniquely transparent

idiom forged as much from the post-war European avant garde as from his

American forebears. Perhaps one of the most important symphonists of his era, Corigliano has to date written three symphonies, each a landscape unto itself. Scored simultaneously for wind orchestra and a multitude of wind ensembles, Corigliano's ambitious, extravagant, and grandly barbarous Symphony No. 3: Circus Maximus (2004) was commissioned by the University of Texas at Austin Wind Ensemble, who presented it on their 2008 tour in Europe and gave its New York première in 2005 at Carnegie Hall. Naxos released a stereo recording of Circus Maximus in 2009, and chose the work as the début recording in its Blu-Ray format. Symphony No. 2 (2001), a rethinking and expansion of the surreal and virtuosic String Quartet (1995), was introduced by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 2000 and earned him the 2001 Pulitzer Prize in Music. Symphony No. 1 (1991), commissioned by Meet the Composer for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra when he was composer-in-residence, channeled Corigliano's personal grief over the loss of friends to the AIDS crisis into music of immense power, color, drama, and scope: performed worldwide by over 150 orchestras and twice recorded, this symphony earned him the prestigious Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition. Corigliano’s theatricality, at once thoughtful and innate, has vivified his eight concerti; his most recent concerto is Conjurer (2008), for percussion and string orchestra. Commissioned by an international consortium of six orchestras for Evelyn Glennie, Conjurer was introduced by the Pittsburgh Symphony in the 2007-2008 season, when the orchestra designated him its Composer of the Year. For Joshua Bell, Corigliano composed Concerto for Violin and Orchestra: The Red Violin (2005). Developed from the themes of the score to François Girard’s film of the same name, which won Corigliano an Oscar in 1999, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra was introduced by the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra under Marin Alsop and recorded by them in 2007. Vocalise (2000), an unusual single-movement wordless concerto for voice, orchestra, and electronics, was commissioned for the millennium by the New York Philharmonic; Kurt Masur led Sylvia McNair in the work’s première. Guitarist Sharon Isbin and the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra under Hugh Wolff introduced Troubadours in 1994. Flutist James Galway and the Los Angeles Philharmonic under Myung-Whun Chung gave the first Pied Piper Fantasy in 1982. Corigliano’s kinetic and elegant Piano Concerto (1967), in which Victor Alessandro led Hilde Somer and the San Antonio Symphony, was his first essay in the genre, but the composer credits his first two concerti for solo winds with changing both his art and his career. It was during the composition of the Oboe Concerto (1975: Humbert Lucarelli, oboe; Kazuyoshi Akiyama, American Composers Orchestra) and, especially, the Clarinet Concerto (1977) that he first used the "architectural" method of composing which empowers him to forge a strikingly wide range of musical materials into arches of compelling aural logic. The première of the Clarinet Concerto, with Stanley Drucker and the New York Philharmonic under Leonard Bernstein, was by contemporary accounts the musical event of the year. While he has composed three large-scale works for voice and orchestra, Corigliano’s lone opera to date is The Ghosts of Versailles (1991), which counterposes the fiction of Mozart and Beaumarchais with the Reign of Terror to create a richly multilayered meditation on the need for, and costs of, personal and social change. The Metropolitan Opera's first commission in three decades, The Ghosts of Versailles succeeded brilliantly with both critics and audiences; the season it opened, Corigliano was elected to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, and Musical America named him its first-ever "Composer of the Year." After triumphs in Chicago, Houston, and Hannover, Germany, The Ghosts of Versailles returned to the American stage in a newly orchestrated, smaller version in June 2009; premiered by the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis and directed by their James Robinson, production runs include Vancouver Opera and the Wexford Festival on a lengthening list of future engagements. Corigliano's two other major vocal works show a comparably lavish and powerful sense of vocal theatre. Mr. Tambourine Man: Seven Poems of Bob Dylan (2000) boldly refashions texts by the iconic songwriter into a compelling monodrama, by turns savage, yearning, and hallucinatory; begun as a song cycle for piano and soprano in 2000, Corigliano rescored the piece for full orchestra and amplified soprano in 2004. Its Naxos recording, on which JoAnn Falletta leads the Buffalo Philharmonic, was released in September 2008 and garnered Grammy awards for both the work itself and for its leading interpreter, the soprano Hila Plitmann. A Dylan Thomas Trilogy (1960, rev. 1999) revisits and combines three of Corigliano's earlier settings of this poet — Fern Hill (1960), Poem in October (1970), and Poem on His Birthday (1976) — with the late Author's Prologue into a "memory play in the form of an oratorio." Scored for boy soprano, tenor, baritone, chorus, and orchestra, A Dylan Thomas Trilogy was recorded in spring 2008 with Leonard Slatkin conducting Sir Thomas Allen and the Nashville Symphony and Chorus; it was released by Naxos in November 2008. Corigliano is one of the few living composers to have a string quartet named for him: its young players banded together after an Indiana University performance of his String Quartet (1995), which Corigliano wrote as a valedictory commission for the Cleveland Quartet and which won him that year’s Grammy Award for best contemporary composition. His first chamber score, Sonata for Violin and Piano (1964), is now a standard of the American violinist’s repertory, having been performed hundreds of times and recorded dozens since the Spoleto Festival awarded the piece first prize in its inaugural Chamber Music Competition. His newest is Winging It: Improvisations for Solo Piano (2008), introduced by Ursula Oppens in May 2009. It joins in his keyboard catalogue the virtuoso showpieces Etude Fantasy (1976) and Fantasia on an Ostinato (1985) for solo piano, and the unique Chiaroscuro (1997), for two pianos tuned a quarter-tone apart. Also recent is his new arrangement of Mr. Tambourine Man (2009) for voice and sextet, which was co-commissioned by the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, who presented the first performance in September 2009, and the ensemble eighth blackbird (who tour the piece in 2010). Like the version of Poem on His Birthday for tenor and eight instruments (1970), Corigliano casts these orchestral pieces for chamber ensemble with no loss of force. Phantasmagoria (2000) revisits themes from The Ghosts of Versailles for cello and piano; Fancy on a Bach Air (1996) varies Bach for solo cello. His earliest songs form the cycle The Cloisters (1965), written with William M. Hoffman, who also wrote the libretto to The Ghosts of Versailles. His latest are a trio of cabaret songs to the lyrics of opera composer-librettist Mark Adamo — End of the Line, Marvelous Invention, and Dodecaphonia (or, They Call Her Twelve-Tone Rose) — introduced by William Bolcom and Joan Morris. Corigliano serves on the composition faculty at the Juilliard School of Music and holds the position of Distinguished Professor of Music at Lehman College, City University of New York, which has established a scholarship in his name. Born in 1938 to John Corigliano Sr., a former concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic, and Rose Buzen, an accomplished pianist and educator, Corigliano has lived in New York City all his life: for the past fourteen years he and his partner, Mark Adamo, have divided their time between Manhattan and Kent Cliffs, New York. His music is published exclusively by G. Schirmer. — October 2009 |

These interviews were recorded in Chicago on December 17, 1987 and

July 9, 2004. Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in

1988, 1990, 1993, 1998, and on WNUR in 2004. The transcription was

made and posted on this website in 2010. It has also been

included in the internet channel Classical Connect.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.