| When honoring him with its Goddard Lieberson

Fellowship, the American Academy of Arts and Letters noted that

“A rare economy of means and a strain of religious mysticism distinguish

the music of James Primosch… Through articulate, transparent textures,

he creates a wide range of musical emotion.” The

New Yorker stated that Primosch “scores with a sure, light

hand” and critics for the New York Times, the Chicago Sun-Times,

the Philadelphia Inquirer, and the Dallas Morning

News have characterized his music as “impressive”, “striking”,

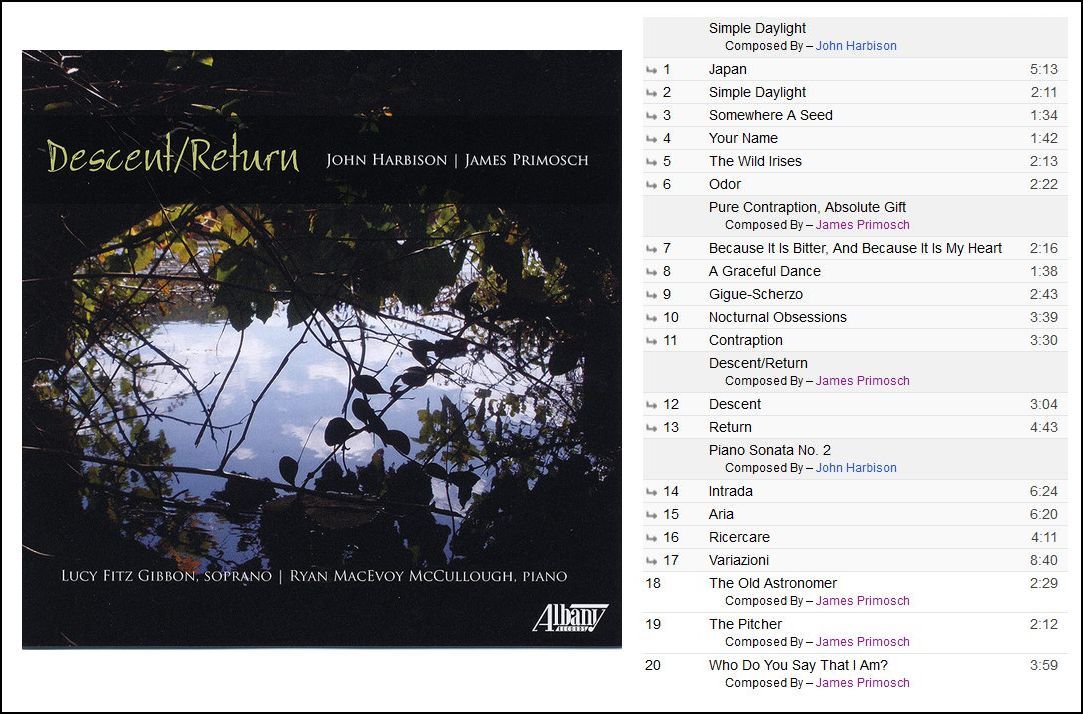

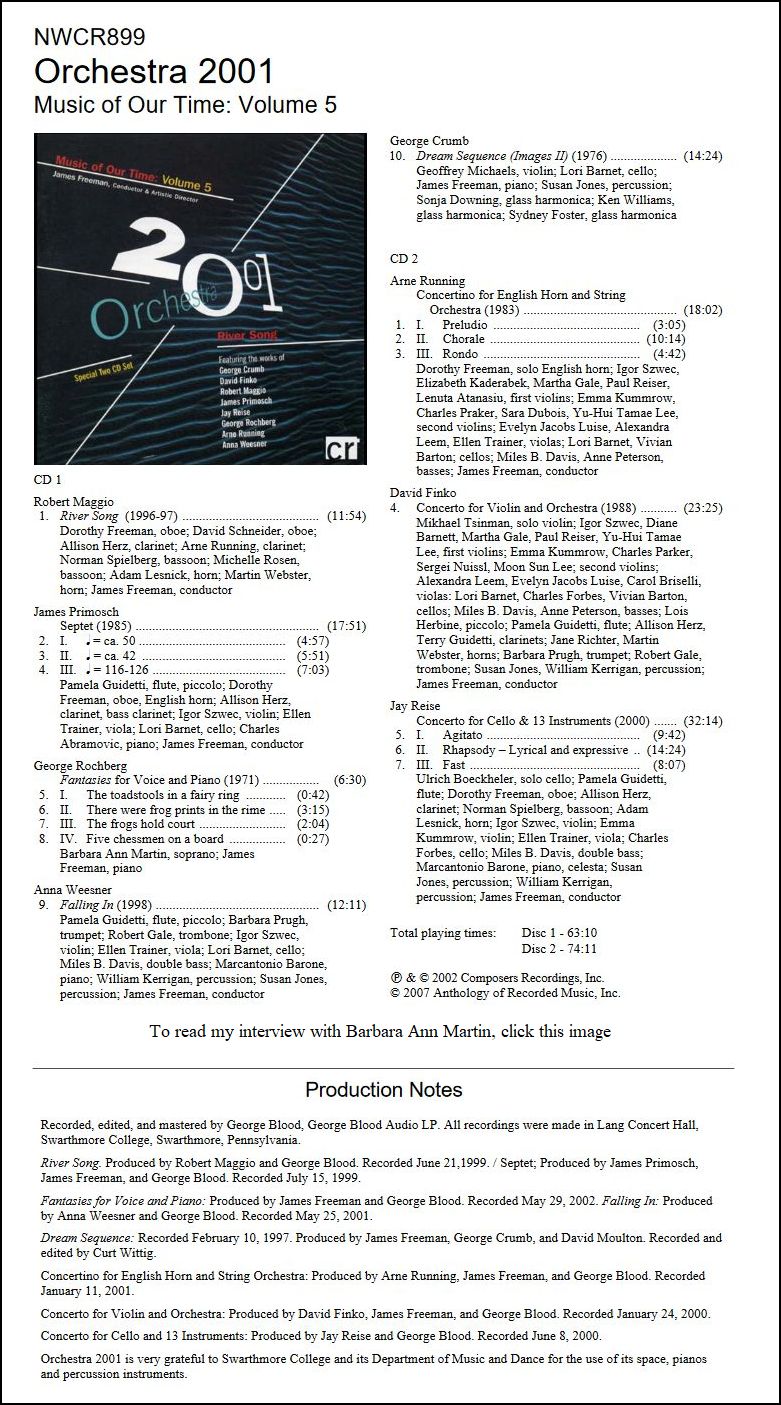

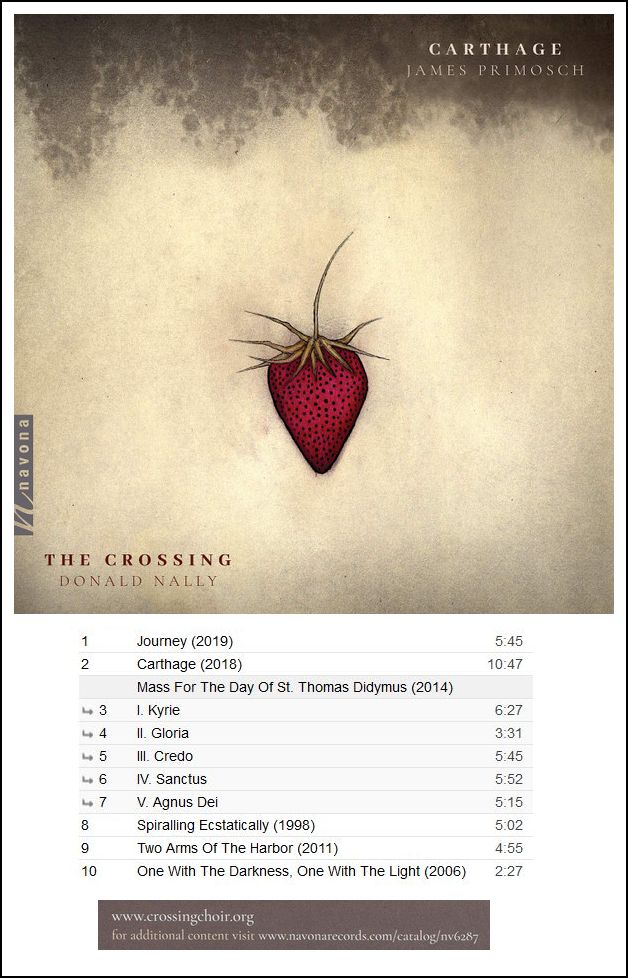

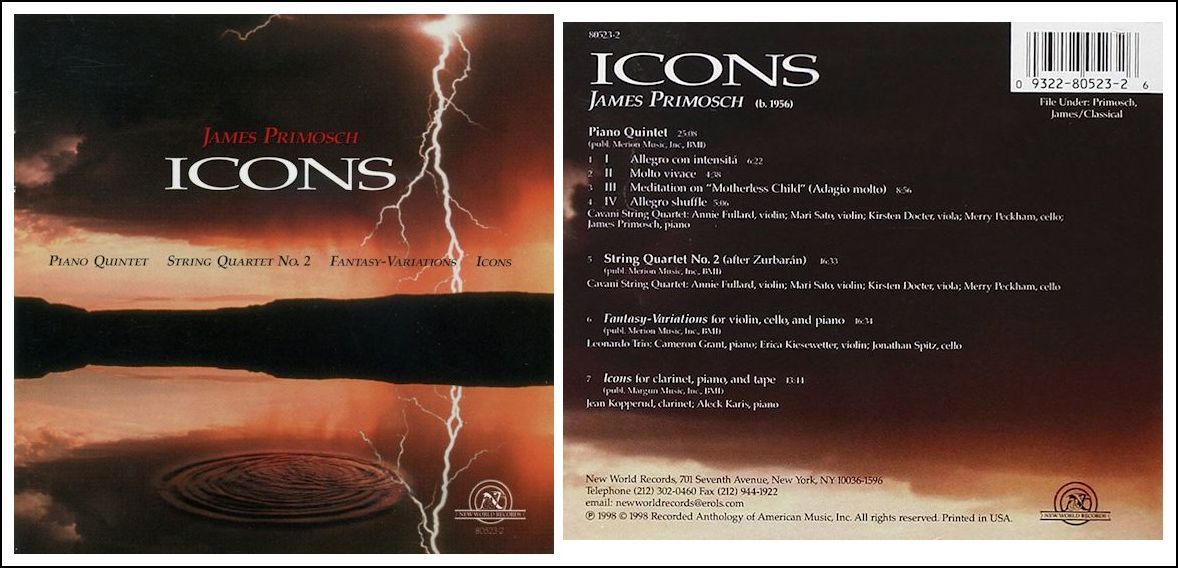

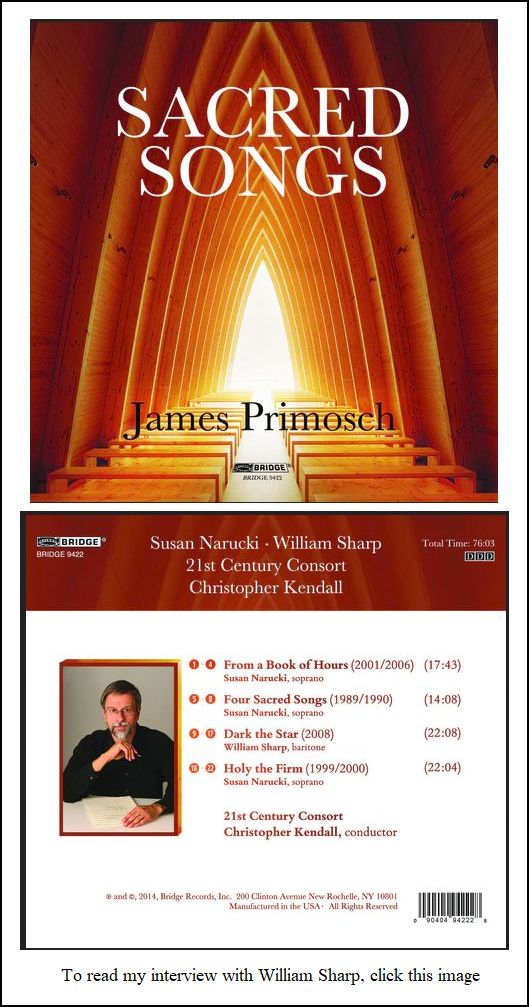

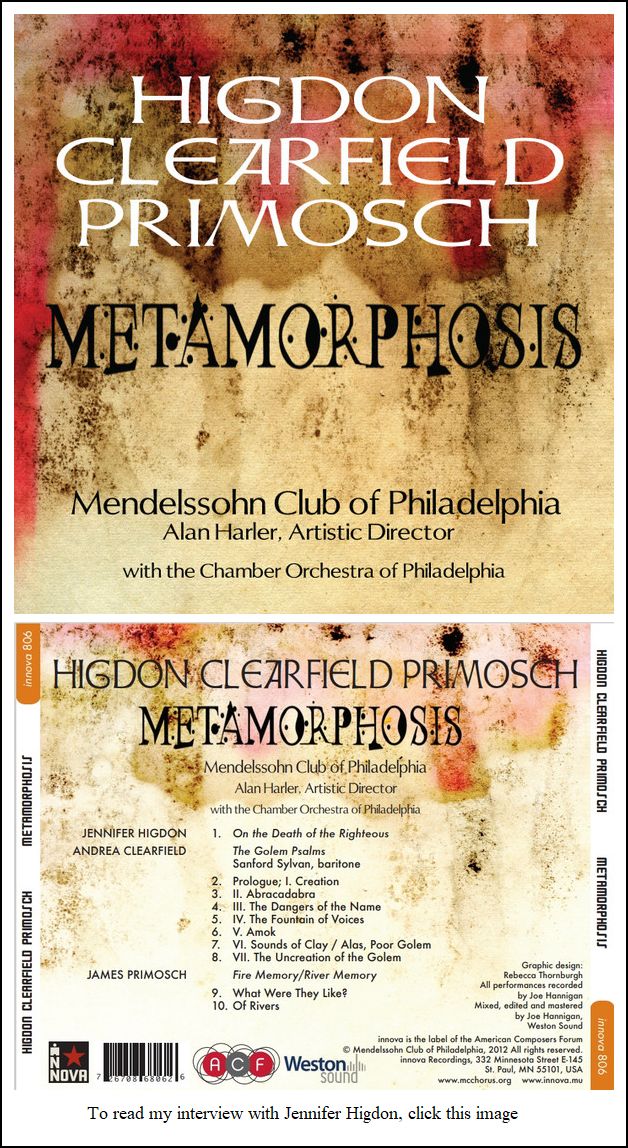

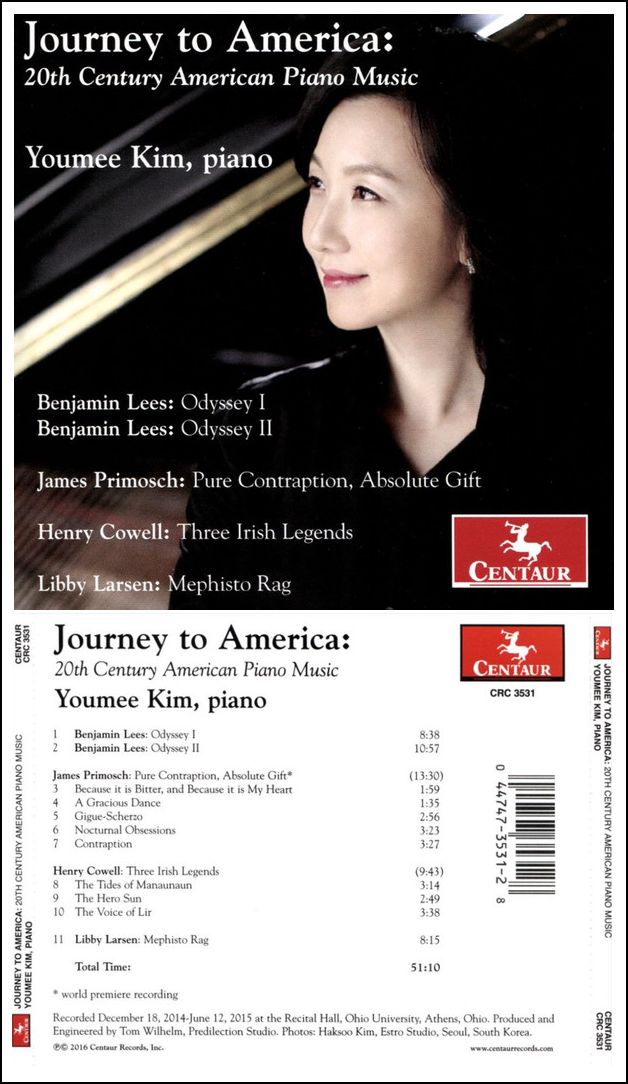

“grandly romantic”, “stunning” and “very approachable”. Primosch’s compositional voice encompasses a broad range of expressive types. His music can be intensely lyrical, as in the song cycle Holy the Firm (composed for Dawn Upshaw) or dazzlingly angular as in Secret Geometry for piano and electronic sound. His affection for jazz is reflected in works like the Piano Quintet, while his work as a church musician informs the many pieces in his catalog based on sacred songs or religious texts. Primosch’s instrumental, vocal, and electronic works have been performed throughout the United States and in Europe by such ensembles as the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, Collage, the New York New Music Ensemble, and the Twentieth Century Consort. His Icons was played at the ISCM/League of Composers World Music Days in Hong Kong, and Dawn Upshaw included a song by Primosch in her Carnegie Hall recital debut. Commissioned works by Primosch have been premiered by the Chicago Symphony, the Albany Symphony, Speculum Musicae, the Cantata Singers, and pianist Lambert Orkis. Recently completed works include a Fromm Foundation commission for Collage New Music, and commissioned pieces for the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society and for Lyric Fest. Among the honors he has received are a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Guggenheim Fellowship, four prizes from the American Academy-Institute of Arts and Letters, a Regional Artists Fellowship to the American Academy in Rome, a Pew Fellowship in the Arts, the Stoeger Prize of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and a fellowship to the Tanglewood Music Center where he studied with John Harbison. [Note that music of both Primosch and Harbison appear on the CD shown below.] Organizations commissioning Primosch include the Koussevitzky and Fromm Foundations, the Mendelssohn Club of Philadelphia, the Folger Consort, the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, the Barlow Endowment, and the Network for New Music. In 1994 he served as composer-in-residence at the Marlboro Music Festival. Recordings of thirty-five compositions by Primosch have appeared on the Albany, Azica, Bard, Bridge, CRI, Centaur, Innova, Navona, and New World labels.

Born in Cleveland, Ohio on October 29, 1956, James Primosch studied at Cleveland State University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Columbia University. He counts Mario Davidovsky, George Crumb and Richard Wernick among his principal teachers. James Primosch is also active as a pianist, particularly in the realm of contemporary music. He was a prizewinner at the Gaudeamus Interpreters Competition in Rotterdam, and appears on recordings for New World, CRI, the Smithsonian Collection, and Crystal Records. He has studied jazz piano and worked as a liturgical musician. Since 1988 he served on the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania. James Primosch, composer, producer, and pianist, passed away on April 26, 2021, at the age of 64. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 2002 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 9, 2002. Portions were broadcast on WNUR the following April, and again in 2004 and 2018. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.