|

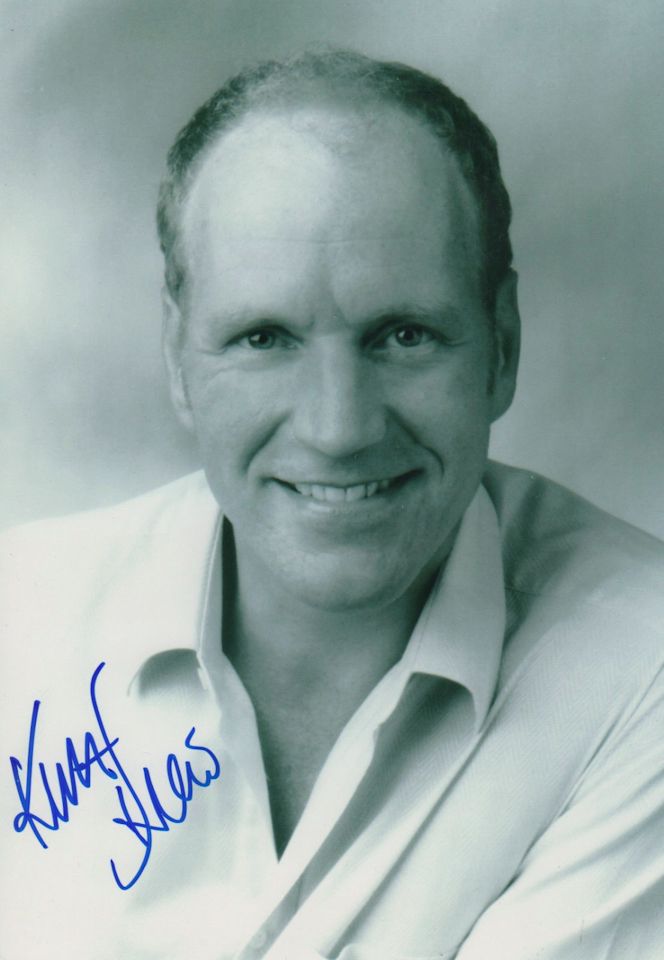

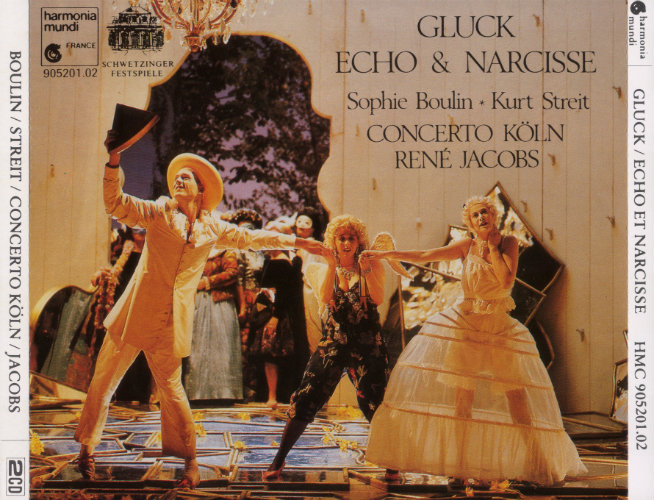

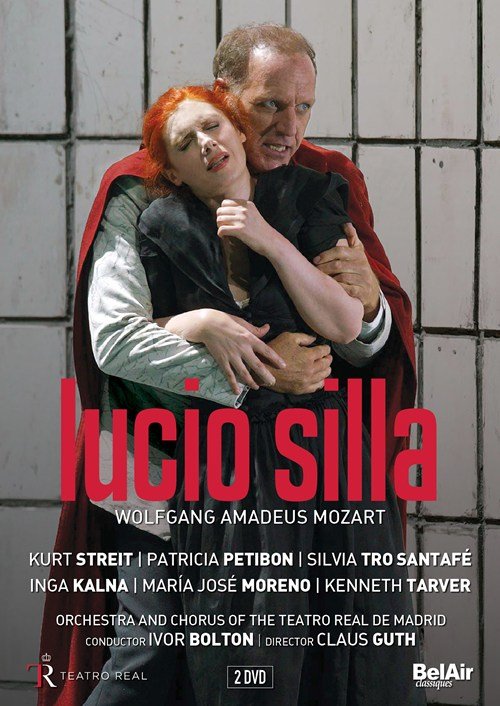

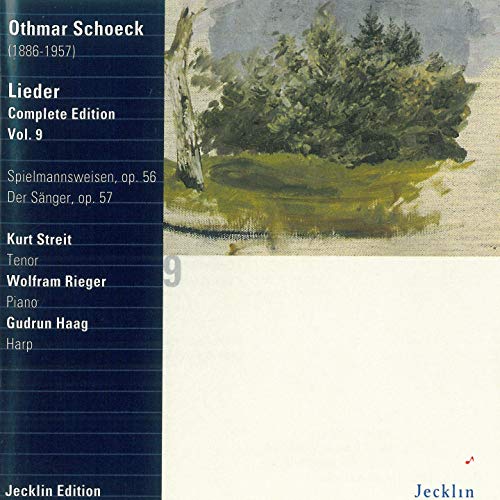

Tenor Kurt Streit, born October 14, 1959 in Fukuoka, Japan, is an Austrian-American tenor. He played guitar as a teenager, and later studied singing with Marilyn Tyler at the University of New Mexico. He went on to become a member of apprentice programs in San Francisco and Santa Fe. He has since performed for leading companies and houses around the world. Considered one of the world’s best Mozart interpreters throughout his career, Streit has performed Die Zauberflöte in 23 different productions around the world (over 150 performances) and Idomeneo in eight different productions—in the opera houses of Naples, Vienna, Madrid, London, San Francisco and others. Performing in numerous productions of Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte and Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Streit has also featured in these and earlier works of Mozart in opera houses such as The Metropolitan Opera in New York, The Vienna State Opera, The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in London, La Scala in Milan, both the Bastille and the Grand Opera in Paris, Teatro Real and the Zarzuela in Madrid, and on the prestigious stages of San Francisco, Tokyo, Aix-en-Provence, Chicago, Munich, Berlin, Rome and Salzburg. Streit’s renown has, in recent years, led him to further success

in his broadening repertoire, encompassing works from composers such

as Berg (Lulu at the Paris Opera), Britten (Death in

Venice at Theater an der Wien), Pfitzner (title role in Palestrina

in Frankfurt), Janáček (Kat’a Kabanova in London,

Amsterdam and Brussels, both tenor roles in Jenufa in

Amsterdam, From the House of the Dead at the Met),

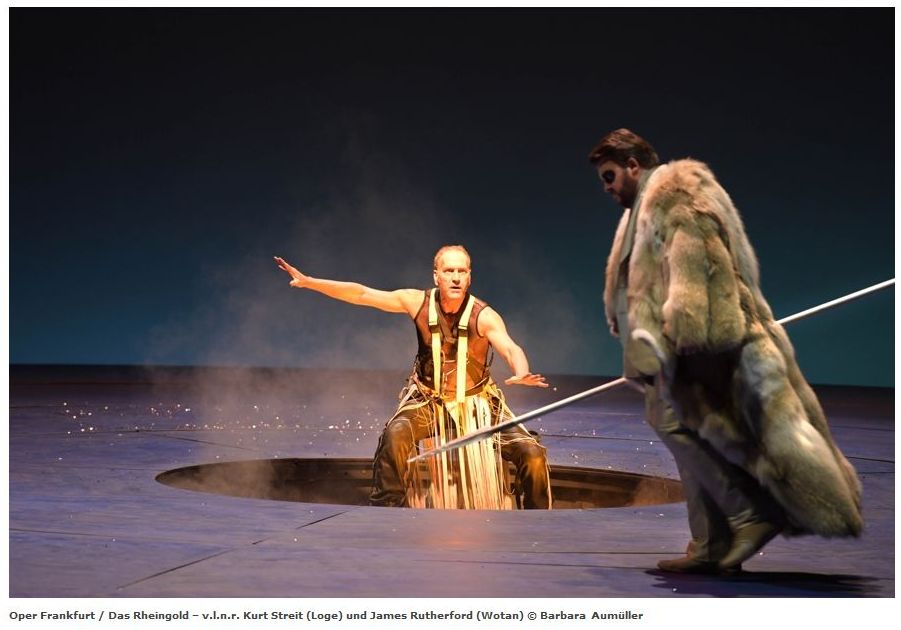

Wagner (Erik in Der Fliegende Hollaender in Barcelona

and Munich, and Loge in Das Rheingold in Frankfurt,

Dresden and Barcelona), Hindemith (Mathis der Maler), Berlioz

(Les Troyens in Geneva, La Damnation de

Faust in Madrid), Bizet (Carmen with Nikolaus Harnoncourt

at the Styriarte Fesitval in Graz), Weber (Euryanthe in Brussels)

and Beethoven (Fidelio in Vienna), all the while keeping his Mozart

interpretations alive with the title roles in La Clemenza di Tito, Lucio

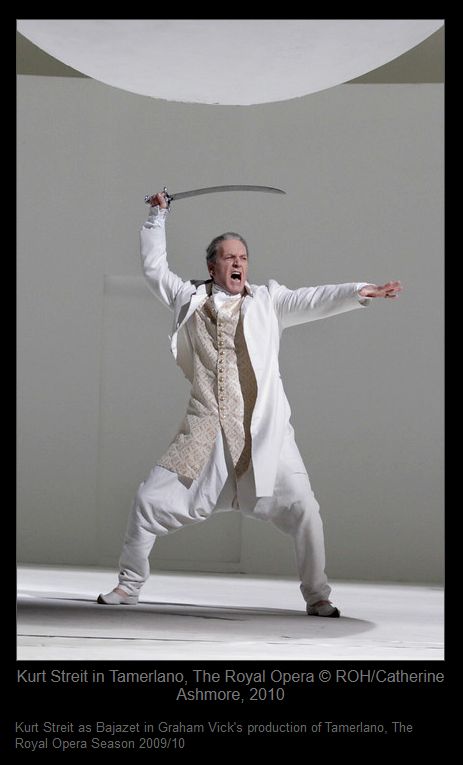

Silla, and Idomeneo. His specialities also include Handel

(Semele and Tamerlano) at the Royal Opera,

Covent Garden, Jephtha and Theodora with

Concentus Musicus in Vienna’s Musikverein, Rodelinda in

Paris, Vienna and Glyndebourne, Partenope in Chicago

and in Vienna, (recorded for Chandos) and Monteverdi — both Ulysse

and Poppea with appearances in Berlin,

Zurich and Los Angeles (shown in photo below).

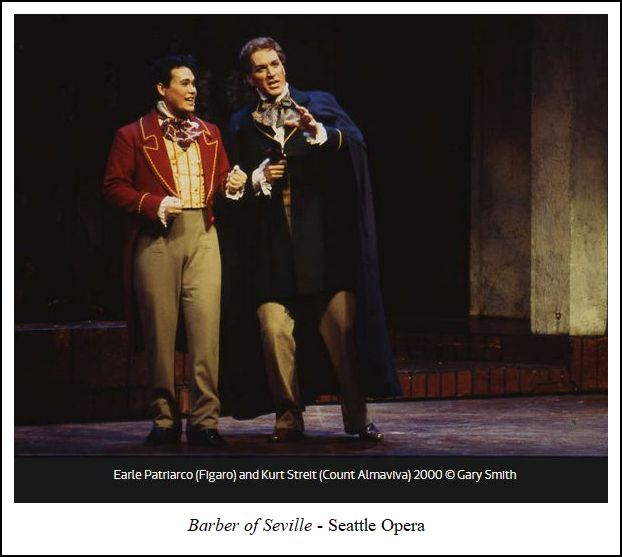

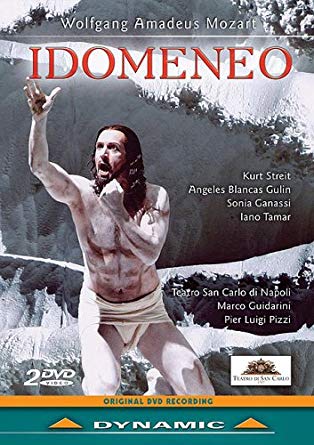

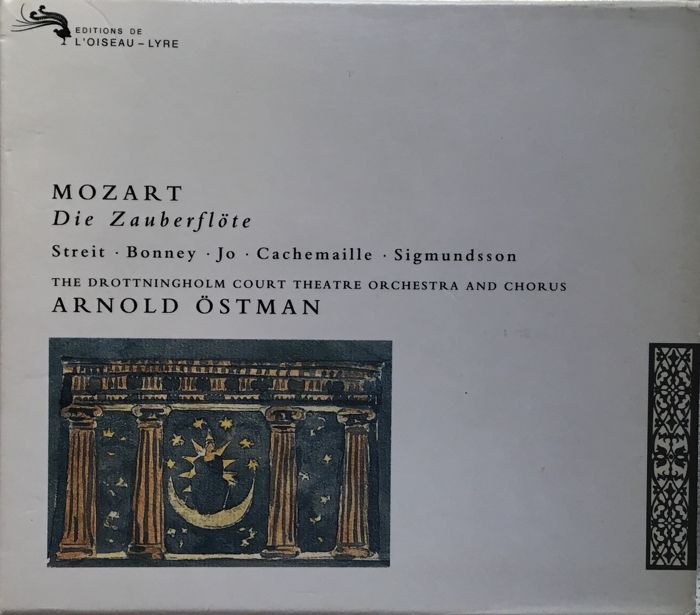

Streit has appeared with the world’s foremost conductors including Harnoncourt, Pappano, Muti, Rattle, Christie, Bolton, Ozawa, Mehta, Maazel, and with the noted symphony orchestras of Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, St. Petersburg, Berlin, Vienna, Paris, Boston, Florence, Stockholm, and all four of London’s major orchestras. A two-time Grammy nominee (Brahms Liebeslieder-Walzer with EMI, and Bach: Cantatas with Harmonia Mundi), Streit can be seen and heard on Warner Music’s DVD of Rodelinda from Glyndebourne and Dynamic’s DVD of Idomeneo from Naples. His discography includes two complete recordings of Così fan tutte with Barenboim (Erato) and with Sir Simon Rattle (EMI) (shown below), Die Zauberflöte (L’Oiseau-Lyre), Die Entführung aus dem Serail (Sony Classical), as well as Cherubini’s Mass in D-minor with Muti (EMI) and Franz Schmidt’s Das Buch mit Sieben Siegeln with Harnoncourt conducting the Vienna Philharmonic (Teldec). More recently he recorded Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Rattle and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (EMI) and the Mozart Requiem with Harnoncourt and Concentus Musicus (BMG). [The information above is mostly taken from the website of his agency, IMG Artists, dated 2018. The following is part of his biography from Covent Garden, and shows a few more of his recent roles.] Streit made his Royal Opera debut in 1992 as Ferrando (Così fan tutte) and has since sung Tamino (Die Zauberflöte), Belmonte (Die Entführung aus dem Serail), Johnny Inkslinger (Paul Bunyan), Cassio (Otello), David (Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg), Jupiter (Semele), Prunier (La rondine), Don Anchise (La finta giardiniera), Boris Grigorjevic (Kát’a Kabanová), the Marquis (The Gambler), Bajazet (Tamerlano - photo below) and Jimmy McIntyre (Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny).

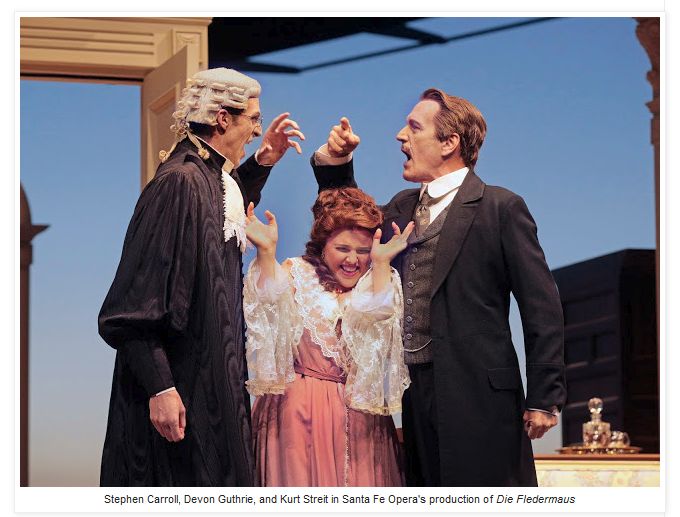

Streit’s repertory includes Alwa (Lulu), Gabriel von Eisenstein

(Die Fledermaus), Hoffmann (Les Contes d’Hoffmann),

Enée (Les Troyens), Loge (Das Rheingold), Jeník

(The Bartered Bride), Albrecht von Brandenburg (Mathis der

Maler), Prince Vasili Golitsyn (Khovanshchina) and the title

role in Palestrina. He has won acclaim for his Mozart and

Handel roles, including Tito (La clemenza di Tito), Idomeneo,

Grimoaldo (Rodelinda) and Jephtha. He performs regularly in concert,

and has recorded for many leading labels. Streit would appear with Lyric Opera of Chicago on four occasions... 1994-95 - Capriccio (Flamand) with Lott, Gilfrey, Rootering,

Golden, Bottone; Davis,

Cox, Tallchief, Schuler In March of 2001, Streit would perform the Serenade for Tenor,

Horn, and Strings of Britten with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and

Dale Clevenger

(Principal Horn of the CSO), conducted by Sir Andrew Davis. Also on

that program were the Symphony #104 of Haydn, the Symphony in Three

Movements by Stravinsky, and the Lyric for Strings by George Walker.

-- Links in this box and below refer to my

interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

As noted above, in the fall

of 1994, Streit was in Chicago for Capriccio by Richard Strauss.

It was around Thanksgiving, and we met on one of the days between

performances. As we settled in for the conversation, this is

how we began . . . . . . .

As noted above, in the fall

of 1994, Streit was in Chicago for Capriccio by Richard Strauss.

It was around Thanksgiving, and we met on one of the days between

performances. As we settled in for the conversation, this is

how we began . . . . . . . KS: Good question, really. I bring my computer with

me [remember, this interview took place in 1994, when computers were

not so convenient, nor ubiquitous!], and I do all my numbers things

by myself — all my finances, and taxes

— and I keep up with that. But that could

only take up a certain amount of time. Gosh, sometimes I wonder

what I do all day long. All of us wonder about that, and we have

our routines. Singers have their routines even if they’re all a

bit different. I sing a lot. I just now finished singing for

about an hour, and I’m going to sing again for an hour after we leave,

so that’s one I thing I definitely do. I practice. I know a lot

of singers who don’t practice [has a sly grin], but I do, definitely.

I definitely learn when practicing and learning new roles, and working out

and trying to keep a bit fit. I also enjoy cooking so I don’t eat

out too much.

KS: Good question, really. I bring my computer with

me [remember, this interview took place in 1994, when computers were

not so convenient, nor ubiquitous!], and I do all my numbers things

by myself — all my finances, and taxes

— and I keep up with that. But that could

only take up a certain amount of time. Gosh, sometimes I wonder

what I do all day long. All of us wonder about that, and we have

our routines. Singers have their routines even if they’re all a

bit different. I sing a lot. I just now finished singing for

about an hour, and I’m going to sing again for an hour after we leave,

so that’s one I thing I definitely do. I practice. I know a lot

of singers who don’t practice [has a sly grin], but I do, definitely.

I definitely learn when practicing and learning new roles, and working out

and trying to keep a bit fit. I also enjoy cooking so I don’t eat

out too much. BD: Is that something you will save for ten or twelve

years down the line?

BD: Is that something you will save for ten or twelve

years down the line?

BD: You know the style.

BD: You know the style. BD: Are the audiences different from America to Europe?

BD: Are the audiences different from America to Europe? BD: Are you then unfairly compared with The Three Tenors?

BD: Are you then unfairly compared with The Three Tenors? BD: Going back to Mozart just for a

moment, is it particularly difficult in The Magic Flute and Entführung,

where you go from singing to speaking?

BD: Going back to Mozart just for a

moment, is it particularly difficult in The Magic Flute and Entführung,

where you go from singing to speaking? BD: That didn’t put the cast out of

balance, because you were such a bigger singer than the rest?

BD: That didn’t put the cast out of

balance, because you were such a bigger singer than the rest? KS: Yes. The only thing, if I’m frustrated with

anything, is what we’ve been talking about, which is my repertoire. I

am so thirsty to learn new repertoire. If there’s any frustration

at all in my career, it’s being labeled as a ‘Mozart Tenor’ and not singing

more varied repertoire. [As noted in the bio-box at the top

of this page, Streit would expand his repertoire to include a wide variety

of roles] I have never sung Alfredo in La Traviata yet,

and I am thirty-five years old. Why? It’s not fair!

I would love to sing that repertoire. My voice is also just now getting

around to growing. When I was thirty, I still had a really small voice,

but in the last five years it’s grown a lot. As you know, it takes

time.

KS: Yes. The only thing, if I’m frustrated with

anything, is what we’ve been talking about, which is my repertoire. I

am so thirsty to learn new repertoire. If there’s any frustration

at all in my career, it’s being labeled as a ‘Mozart Tenor’ and not singing

more varied repertoire. [As noted in the bio-box at the top

of this page, Streit would expand his repertoire to include a wide variety

of roles] I have never sung Alfredo in La Traviata yet,

and I am thirty-five years old. Why? It’s not fair!

I would love to sing that repertoire. My voice is also just now getting

around to growing. When I was thirty, I still had a really small voice,

but in the last five years it’s grown a lot. As you know, it takes

time.

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 25, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two days later, and again in 1999. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.