|

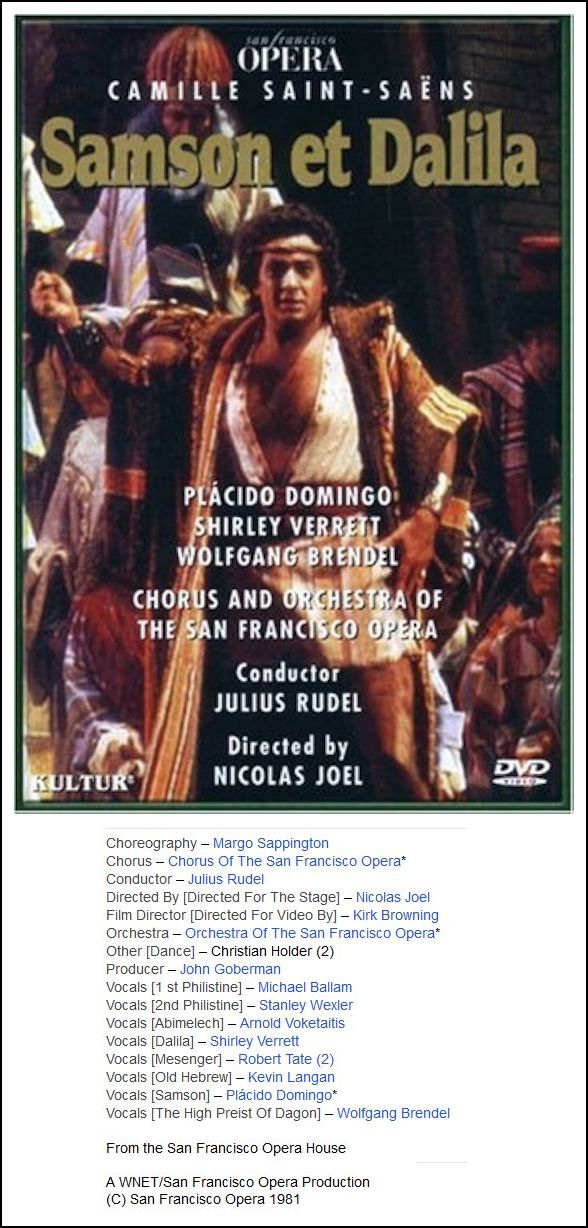

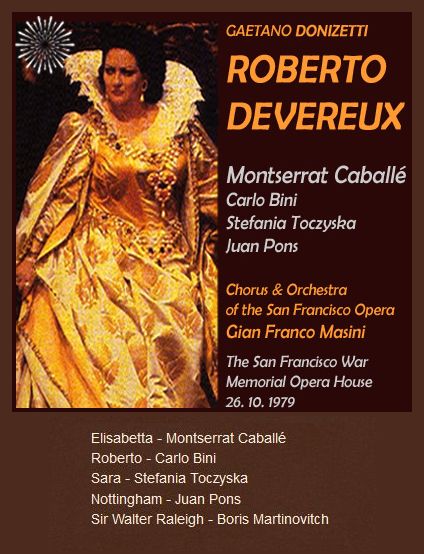

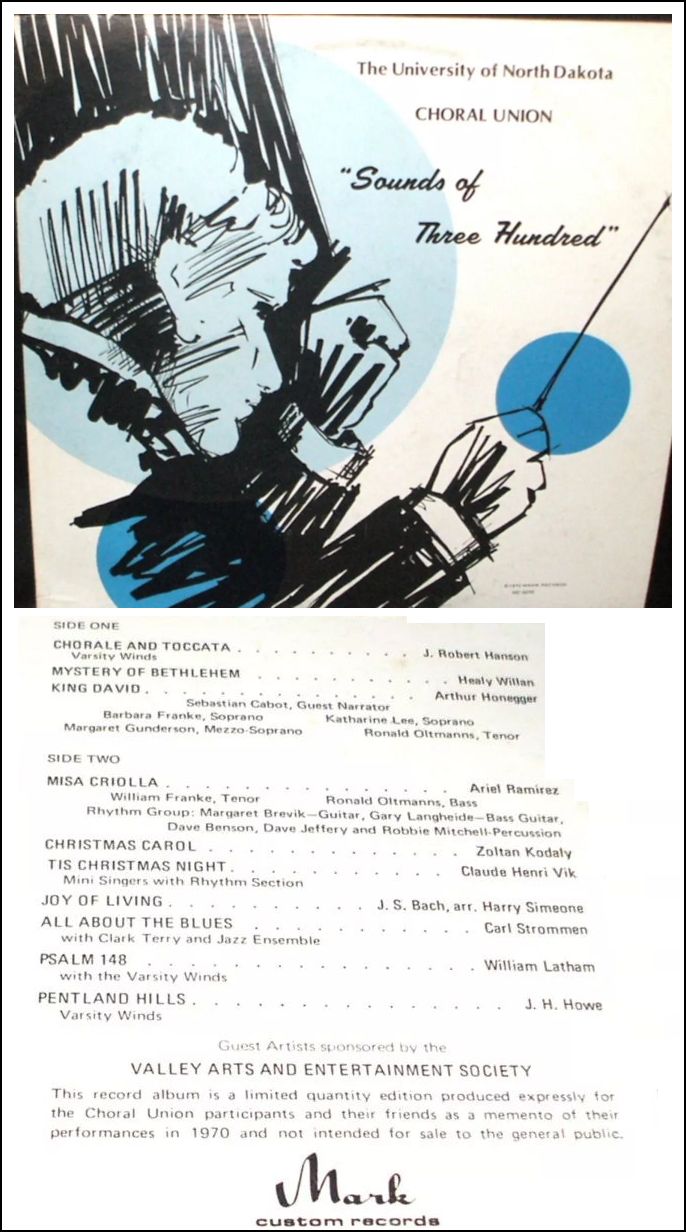

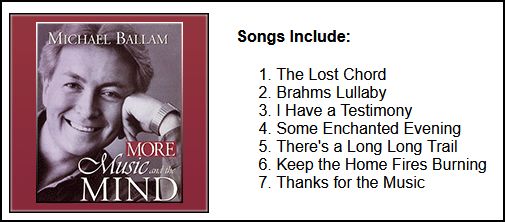

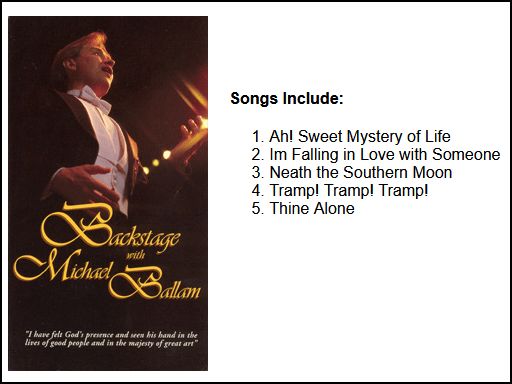

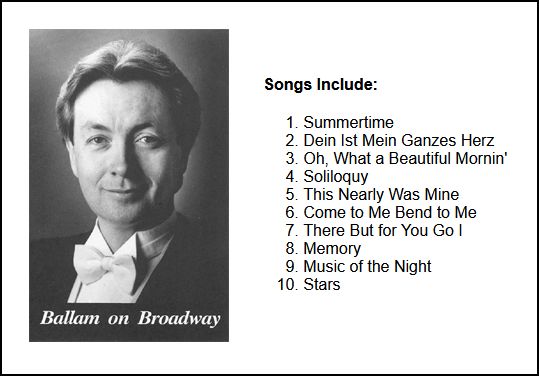

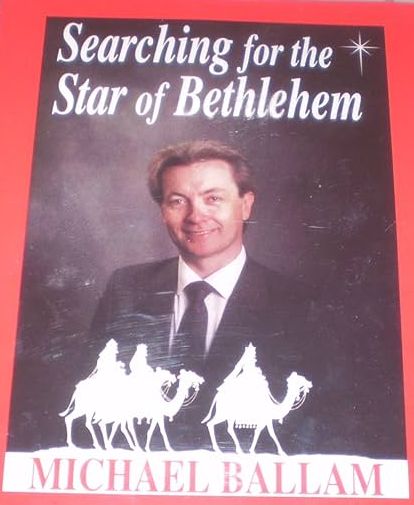

Michael Ballam (born August 21, 1951) has received critical acclaim with the major opera companies of the USA and a recital career in the most important Concert Halls of every continent. His operatic repertoire includes more than 700 performances of over 110 major roles, sharing the stage with the world's greatest singers including Roberta Peters, Jerome Hines, Joan Sutherland, Kiri Te Kanawa, Birgit Nilsson, Beverly Sills, Plácido Domingo and Ethel Merman performing regularly with such companies as the Chicago Lyric, San Francisco, Santa Fe, Dallas, Washington, Philadelphia, St. Louis and San Diego Operas. He has performed on every continent, in 80 countries. At the age of 24, Mr. Ballam became the youngest recipient of the degree of Doctor of Music with Highest Distinction in the history of Indiana University. An accomplished pianist and oboist, he is the Founder and General Director of the Utah Festival Opera, which is fast becoming one of the nation's major Opera Festivals. Professor of Music for the past 24 years at Utah State University, he has also been a faculty member at Indiana University, The Music Academy of the West, University of Utah, Brigham Young University (where he was awarded the Teaching Award in Continuing Education in 1992) and guest lecturer at Stanford, Yale, BYU Idaho, Catholic University and Manhattan School of Music. In 1987, Dr. Ballam became aware that the Capitol Theatre on Main Street in Logan, Utah, had changed ownership for the first time since its debut in 1923. Originally used as an opera house, ballet recital hall, vaudeville house, roadhouse and movie palace, it became closed to live performances in 1958. From that point forward, the theater was used only for motion picture screening. With changing tastes in motion pictures, a 1,500-seat auditorium was too large for movies from the 1970's on. In 1982, the Capitol began showing only second and third run films and fell into disrepair and misuse. Having performed on that stage in 1956 at the age of 5, Ballam had a great love for the theater and knew the magic she was capable of creating. Concerned that the theater may be torn down, or altered to a different use, he approached the new owner Eugene Needham III, asking him to give the theater to Logan City. Explaining his vision of restoring the theater to its original glory, it became the property of the people of the region. Thus began a 5 year, $6.5 million dollar renovation, expanding the stage house, and linking with what became the Bullen (Arts) Center. The newly named Ellen Eccles Theatre opened on January 8, 1993 becoming the new home of the Utah Festival Opera and Musical Theatre, (UFOMT) founded by Ballam. The Festival's 1993 Inaugural Season contained an opera, two operettas and one musical. It soon rose to national then international prominence, growing from an annual budget of $300,000 to $4,500,000 in 2019. During its 27 seasons, UFOMT has produced a total of 181 productions, employing 21 full-time employees and over 300 seasonal employees. In 1998 Ballam renovated the Historic Dansante Building, a 45,000 square foot arts facility, containing 4 rehearsal spaces, 10 practice rooms, 12 executive offices, reception center, dining room, auditorium, set, props and costume shops. In 2016 Ballam completed the renovation of the Utah Theatre, a 1923 movie house, now transformed into a state-of-the-art Performing Arts Center capable of any form of performance, containing a full-fly stage house, proscenium, orchestra pit, rehearsal space, dressing rooms, rooftop garden and a Mighty Wurlitzer Organ. During his 52 year career as a professional opera singer he has

produced, directed or starred in 349 professional productions. He is

the author of over 40 publications and recordings in international distribution,

has a weekly radio program on Utah Public Radio, starred in 3 major

motion pictures and appears regularly on television. Dr. Ballam serves

on the Board of Directors of twelve professional Arts organizations.

In 1996 he was designated one of the 100 Top Achievers in the State of

Utah by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of the U.K., appointed Artist

Extraordinaire by the Governor of Utah in 2003, given Honorary Life Membership

to the Utah Congress of Parents and Teachers, received the "Excellence

in Community Teaching Award" from the Daughters of the American Revolution

in 2007 and was awarded the Gardner Award by the Utah Academy of Science,

Arts and Letters, for "Significant Contributions in the Humanities to the

State of Utah" in 2010. == Biography is from the Artist's website

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

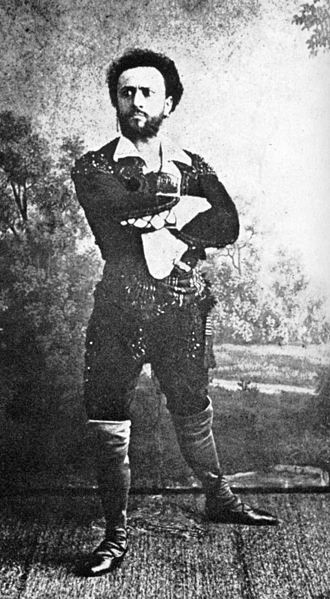

Paul

Lévy, known as Lhérie, (October 8, 1844 - October 18, 1937).

His father Victor Lhérie was a comic actor and vaudeville author,

and his uncle Léon-Lévy Brunswick, comic opera librettist,

co-wrote the libretto for Postillon de Lonjumeau by

Adolphe Adam. By

his own admission, Lhérie was not a born tenor. After

the Conservatory, he joined the Opéra-Comique troupe, where he debuted

in 1865 in Auber's L'Ambassadrice. He

then created the role of Charles II in Don Cesare de Bazan by Massenet.

His

modest qualities as a singer attracted some criticism: “Mr. Lhérie,

intelligent and a good musician, persists in wanting to expand his little

voice to the point of shouting; this

is the reversal of the problem: the container must be larger than the content.

»

(Le Figaro, December 15, 1872).  Then an event occurred by chance which would serve him well: the first

tenor Duchêne, who fell ill, had to give up singing Romeo and Juliet.

Lhérie

replaced him, and Bizet heard him that evening. Bizet

was charmed by the tenor's acting talents so much so that he chose him,

against the advice of du Locle, to be Don José during the creation

of Carmen [as seen in the photo at right]. The

reception was lukewarm: “Lhérie does not give enough character to

the Havanese Don José. It

is true that the Don José of the play has ceased to be that of the

novel. »

(Le Figaro, March 5, 1875). “Lérie

has warmth and distinction; unfortunately

his voice does not always obey him; too

often she is her master's mistress. »

(La Presse, November 21, 1875)

Then an event occurred by chance which would serve him well: the first

tenor Duchêne, who fell ill, had to give up singing Romeo and Juliet.

Lhérie

replaced him, and Bizet heard him that evening. Bizet

was charmed by the tenor's acting talents so much so that he chose him,

against the advice of du Locle, to be Don José during the creation

of Carmen [as seen in the photo at right]. The

reception was lukewarm: “Lhérie does not give enough character to

the Havanese Don José. It

is true that the Don José of the play has ceased to be that of the

novel. »

(Le Figaro, March 5, 1875). “Lérie

has warmth and distinction; unfortunately

his voice does not always obey him; too

often she is her master's mistress. »

(La Presse, November 21, 1875) After the creation of Carmen, Lhérie converted to a baritone, and traveled throughout Europe and America. Returning to Paris, he led a long career as a professor at the Conservatory. It was not because of his singing that he hit the headlines the most. He was taken to court in 1885 by two women to whom he was married, each of whom ended up obtaining a pension! He died at a very old age in 1937, crowned with the title of Dean of French singing. He marks the role of Don José with his acting talents, and, after him, we begin to consider that the role requires an actor rather than a singer. == Biography above is a translation from the website of the Opéra

Comique,

listing those who have sung the role of Don José there After studying in Paris, Lhérie made his debut at the Opéra-Comique in 1866 as Méhul's Joseph. He created the role of Charles II in Massenet's Don César de Bazan in 1872, Kornélis in Camille Saint-Saëns's La princesse jaune in 1872, Benoît in Delibes's Le roi l’a dit in 1873, and Don José in Carmen by Bizet in 1875. Bizet and Lhérie became friends during the preparations for Carmen. They would swim together in the Seine during the singer's visits to the composer's house in Bougival. He became a baritone in 1882, singing Posa in the first performance of the Italian revised version of Verdi's Don Carlos at La Scala, Milan, two years later. He also spent time during the 1880s at Covent Garden in London, where he performed Zurga (in Les Pêcheurs de Perles), Rigoletto, Germont (La Traviata), Luna (Il trovatore), and Alphonse (La favorite). He sang Iago in Brescia in 1887 with Adalgisa Gabbi, José Oxilia and conductor Franco Faccio. He also sang Zurga and other roles in an Italian season at the Théâtre de la Gaîté in 1889, and created the role of Simeone Bardi in the premiere of Godard's Dante in 1890 at the Opéra Comique, having just reprised Zampa for his reappearance at the Salle Favart. In Rome at the Teatro Costanzi on 31 October 1891, he was the first Rabbi David in the premiere of Mascagni's L'amico Fritz (he himself was Jewish) and repeated the role in Monte Carlo the same year. In 1894, he created Gudleik in Franck's Hulda, also in Monte Carlo. Lhérie retired from the stage in 1894. In the last years of his life he taught opéra comique and opera at the Paris Conservatoire, prize-winners among his pupils included Léon Rothier, David Devriès, Suzanne Cesbron-Viseur, Ginette Guillamat and Geneviève Vix. |

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 29, 1982. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.