| William Stone has had an operatic

career at the international level for over thirty five years. He has sung

extensively in the major opera houses of Europe and especially in Italy,

where he twice opened the May Festival in Florence, first as Wozzeck

with Bruno Bartoletti,

and then, as Orestes, in Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride under

Riccardo Muti. His creation of the role of Adam for the Lyric Opera of Chicago's

world premiere of Penderecki's

Paradise Lost, was followed by his debut at La Scala in its

European premiere and a performance at the Vatican for Pope John Paul II.

With Sir Georg Solti,

he toured with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe in the role of the Count

in Le nozze di Figaro. He has sung lead roles with the main opera

companies in Rome, Genoa, Naples, Venice, Paris, Toulouse, Lille, Amsterdam,

Bonn, Stuttgart, Brussels and Amsterdam.

His North American opera engagements included the Metropolitan Opera (Moses und Aron, Wozzeck, La traviata, Sly, Die Fledermaus, Romeo et Juliette, Lucia, Madama Butterfly), and roles for over a decade at the New York City Opera, notably as the Count in Le nozze di Figaro in a Live from Lincoln Center telecast, and the title role in new productions of Hindemith's Mathis der Maler, and Busoni's Doktor Faust. As a concert artist, Stone has appeared with every major orchestra

in the country, including the New York Philharmonic under Kurt Masur and the Boston

Symphony Orchestra with Seiji Ozawa conducting the premieres of Takemitsu's My Way

of Life, and Kirchner's

Of Things Exactly as They Are. His long relationship with

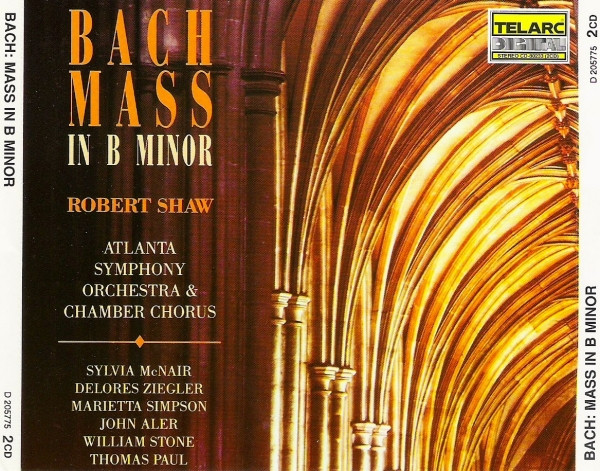

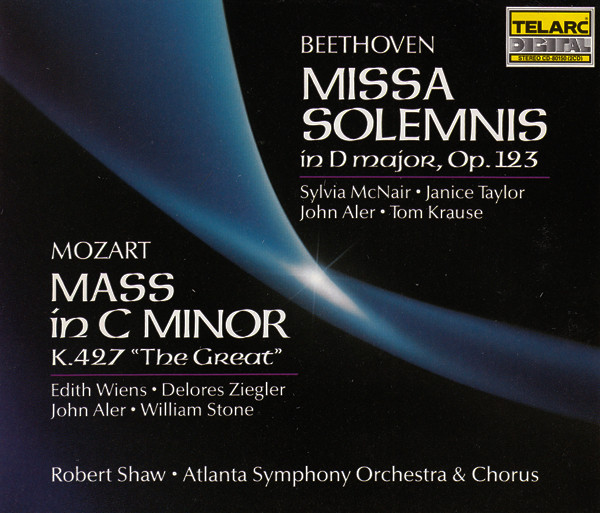

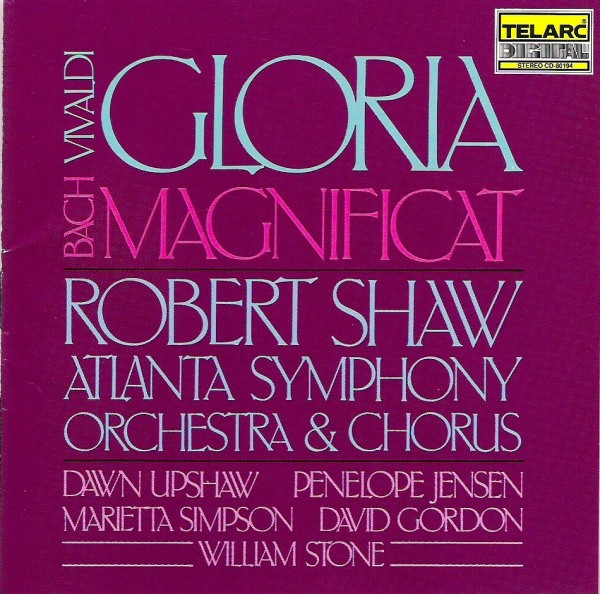

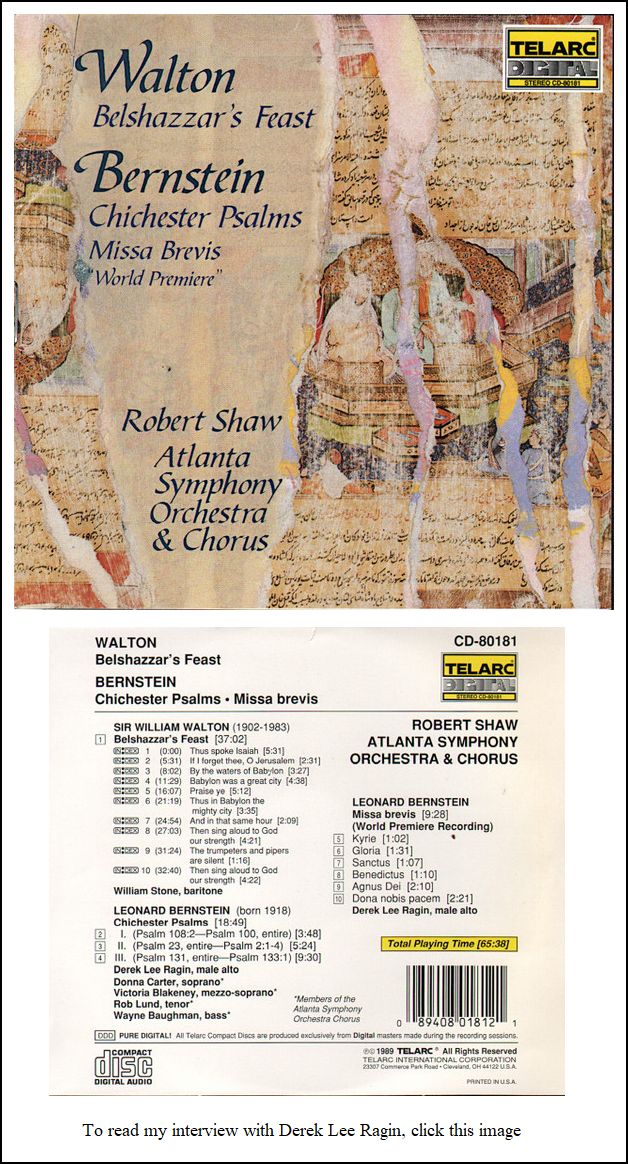

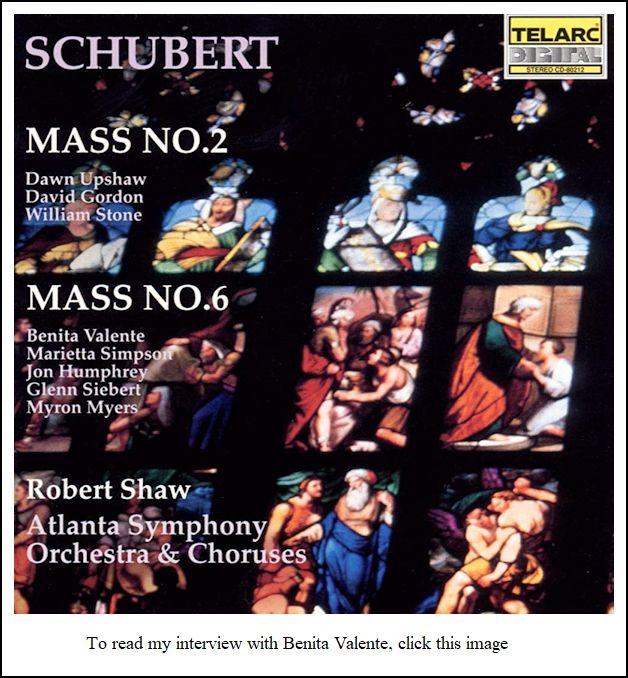

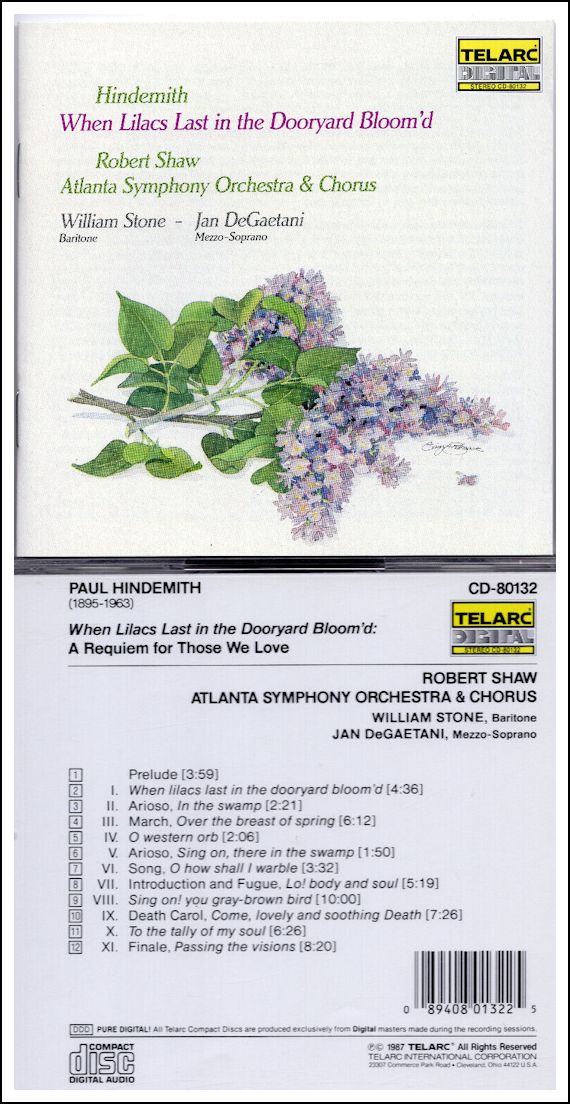

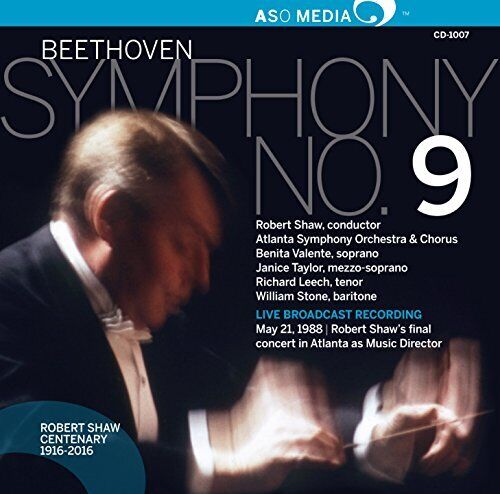

Robert Shaw resulted

in acclaimed performances of the monumental choral works and over a dozen

recordings, including the two Grammy Award recordings of Hindemith's When

Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd, and Walton's Belshazaar's Feast,

and an Historic Live Performance Edition of Ein Deutches Requiem

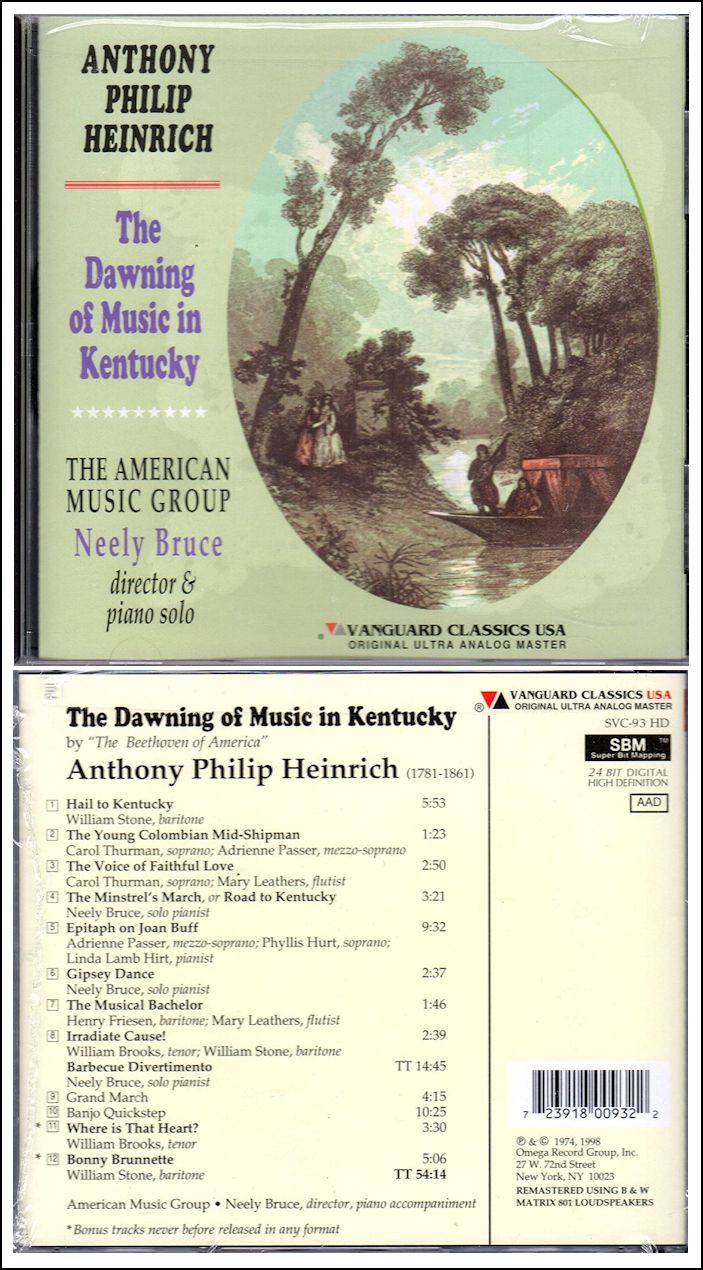

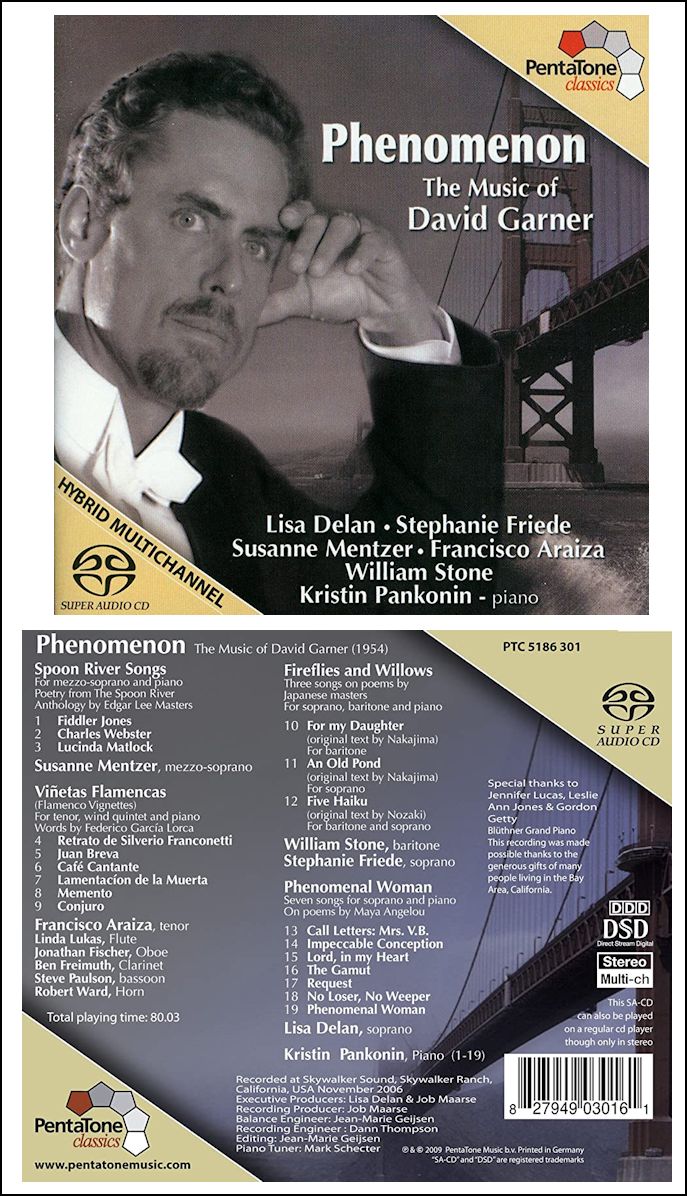

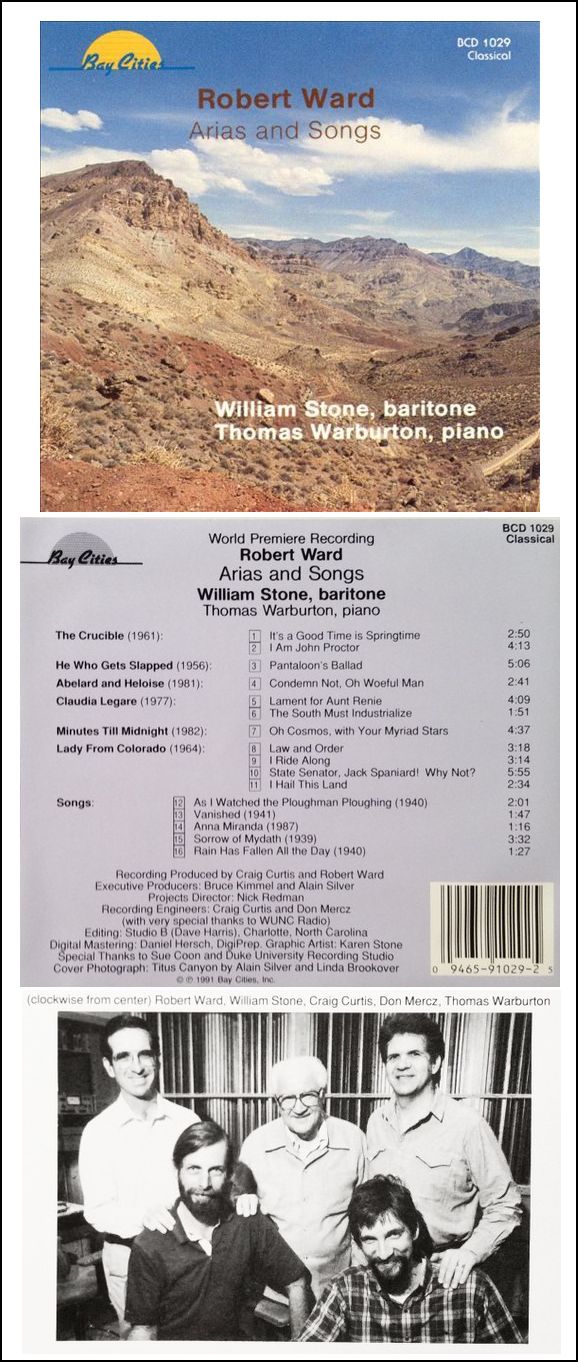

with the Cleveland Orchestra. Other recordings include The Songs and

Arias of Robert Ward,

and DVDs of Carnegie Hall's Performance Series of Hindemith's When

Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd, and Verdi's Falstaff with

José van Dam.

== Biography from the artist's official website

(June, 2023)

== Links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 15, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following week. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.