Kathleen Kuhlmann at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1976 - [Opening Night] Tales of Hoffmann (Voice of Antonia’s

Mother) with Domingo/Johns,

Welting, Cortez,

Eda-Pierre,

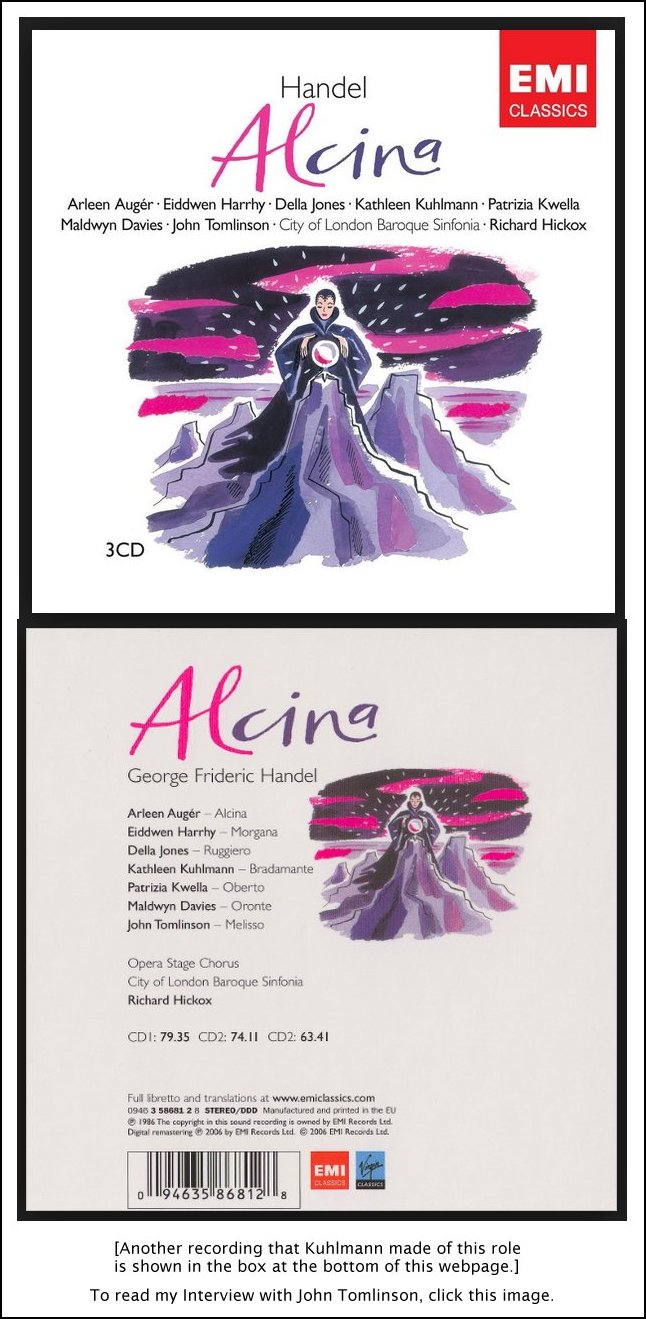

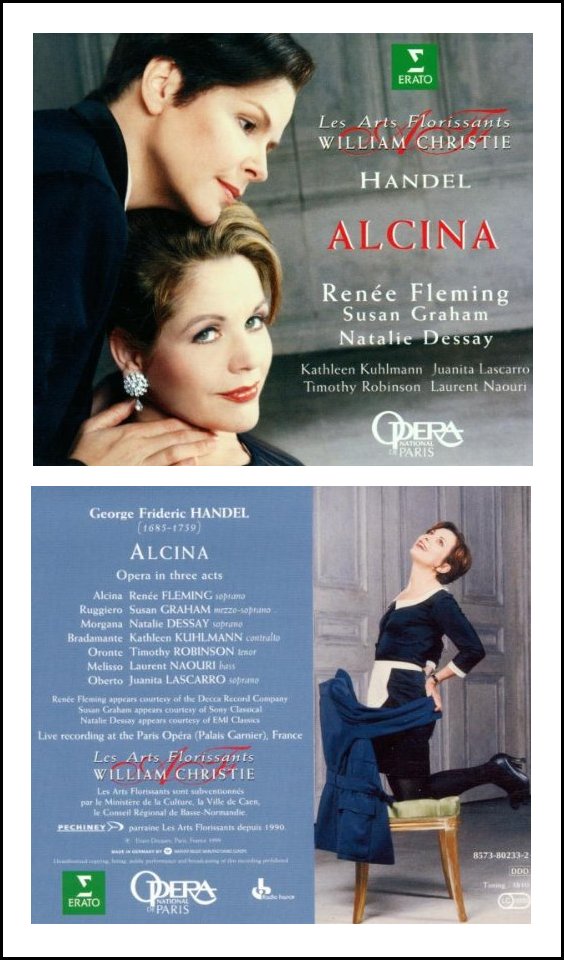

Mittelmann, Andreolli, Voketaitis; Bartoletti, Puecher (director), Frigerio (designer) Rigoletto (Giovanna) with Mittelmann/Manuguerra, Kraus, Mauti-Nunziata, Casarini; Chailly, Sequi (director), Pizzi (designer) Tosca (Shepherd Boy) with Neblett, Pavarotti, MacNeil, Andreolli, Tajo; López-Cobos, Gobbi (director), Pizzi (designer) Love for Three Oranges (Smeraldina) with Barlow, Little, Trussel, Titus, Gill, Tajo; Bartoletti, Chazalettes (director), Santicchi (designer) 1977 - Idomeneo (Cretan Lady) with Tappy, Ewing, Eda-Pierre/Shade, Neblett, Little, Shirley; Pritchard, Ponnelle (designer and director) Orfeo (Shepherd/Blessed Spirit) with Stilwell, Shade, Zilio; Fournet, Sequi (director), Samiritani (designer) Callas Tribute Concert with Vickers, Neblett, Stilwell, Gobbi (speaker), and others; Bartoletti, Fournet Manon Lescaut (Musician) with Chiara, Merighi, Nolen, Montarsolo; Bartoletti/Sanzogno, DeLullo (director), Pizzi (designer), Schuler (lighting) 1978 - [Opening Night] Fanciulla del West (Wowkle) with Neblett, Cossutta, Mastromei; Bartoletti, Prince (director), Eugene & Franne Lee (designers) Salome (Page) with Bumbry, Dunn, Ulfung, Bailey, Little; Klobučar, Poettgen (director), Wieland Wagner (designer) Madama Butterfly (Kate) with Hayashi, Merighi/Moldoveanu, Romero, Andreolli; Chailly, Overton (director), Ming Cho Lee (designer) 1979 - Love for Three Oranges (Clarissa) with Suliotis, Little, Trussel, Nolen, Gill, Tajo; Prêtre, Chazalettes, Santicchi Rigoletto (Maddalena) with Manuguerra/Elvira, Blegen, Pavarotti, Gill; Chailly, Sequi, Pizzi Andrea Chenier (Bersi) with Domingo, Marton, Bruson, Gordon; Bartoletti, Gobbi (director), Samiritani (designer) 1984 - Barber of Seville (Rosina) with Raftery, Araiza, Siepi, Bruscantini; Bartoletti, Sciutti (director), Peter J. Hall (designer) 1995-96 - Xerxes (Amastris) with Murray, Robson, Futral, Hagley, Langan; Nelson, Hytner (director), Felding (designer) 1999-00 - Alcina (Bradamante) with Fleming, Larmore, Dessay, Blake; Nelson, Carsen (director), Hoheisl (designer) -- Names which are links refer

to my Interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

|

BD:

Is it good that all these pieces are coming to light again?

BD:

Is it good that all these pieces are coming to light again?|

Review/Opera; Reason on Holiday (but in Love Isn't

It Always?)

By MICHAEL KIMMELMAN Published in The New York Times, March 4, 1989 The Metropolitan Opera revived one of

its more charming productions and introduced a fine mezzo-soprano when the

company staged the season's first performance of Massenet's ''Werther'' on

Thursday evening. Making her debut in the role of Charlotte, Kathleen Kuhlmann

sang easily and sweetly and without strain, and she looked entirely at home

in the role of the reticent lover. If we are to accept that an impetuous young

man would commit suicide when rebuffed by a woman he barely knows, then Ms.

Kuhlmann's Charlotte makes a reasonable cause. (...) [Also

in the cast were Neil Shicoff,

Bernd Weikl, Dawn Upshaw,

and Renato Capecchi,

conducted by Jean Fournet.]

|

KK: That’s an interesting question. I

talked with Janine Reiss about that, and she was saying how very sad it is

that you sometimes miss a person by just five minutes. Perhaps if Charlotte’s

mother hadn’t died, or if the mother had met Werther, perhaps things would

have been different. Ultimately, though, it might be that Charlotte

and Werther would never have been happy together because he might not have

been the right type of man for her. It’s always hard to tell what

would happen between two people who are in a situation where their love cannot

be realized. One often builds up a real romantic image of love in a

situation like that. It’s wonderful to long for a romantic ideal, but

usually you can’t live in that atmosphere for long. It’s like a bubble

that bursts. One has to get on with living, and there has to be something

more than just a romantic love in live. The whole situation with Charlotte

and Werther is kind of a forbidden love, and that’s why it’s all the more

attractive. They often make Albert out to be rather a dry and uninteresting

character, but I find his music in the first act to be beautiful.

KK: That’s an interesting question. I

talked with Janine Reiss about that, and she was saying how very sad it is

that you sometimes miss a person by just five minutes. Perhaps if Charlotte’s

mother hadn’t died, or if the mother had met Werther, perhaps things would

have been different. Ultimately, though, it might be that Charlotte

and Werther would never have been happy together because he might not have

been the right type of man for her. It’s always hard to tell what

would happen between two people who are in a situation where their love cannot

be realized. One often builds up a real romantic image of love in a

situation like that. It’s wonderful to long for a romantic ideal, but

usually you can’t live in that atmosphere for long. It’s like a bubble

that bursts. One has to get on with living, and there has to be something

more than just a romantic love in live. The whole situation with Charlotte

and Werther is kind of a forbidden love, and that’s why it’s all the more

attractive. They often make Albert out to be rather a dry and uninteresting

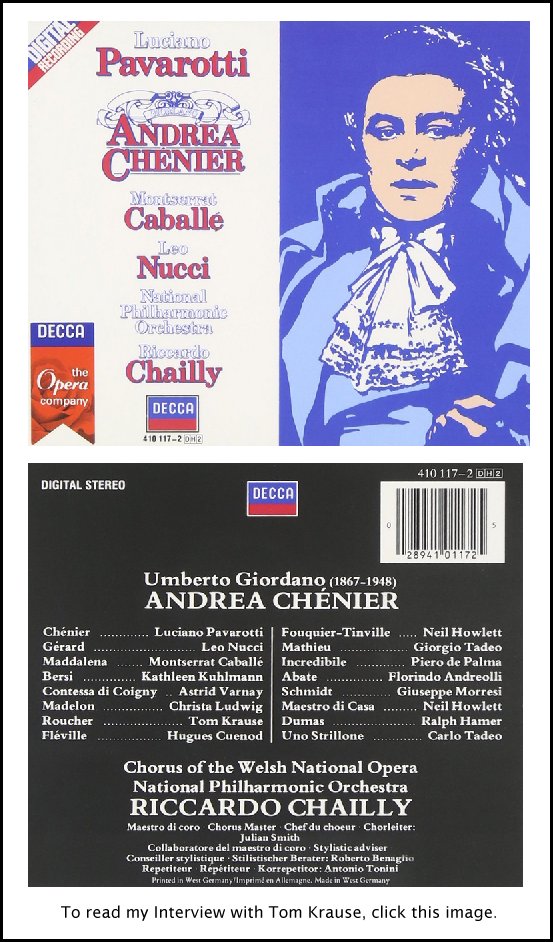

character, but I find his music in the first act to be beautiful. KK: I haven’t made very many. I enjoyed

doing Bersi in Andrea Chenier [shown at right] because I had done the

role onstage. It was very well prepared. We had the coach who

had worked with us there every day there was a recording session. I

learned an awful lot. I also enjoyed going to Dresden to be a Valkerie

in Maestro Janowski’s

recording of Die Walküre.

The orchestra is incredible, and it was nice to be singing with such a lovely

group of young singers.

KK: I haven’t made very many. I enjoyed

doing Bersi in Andrea Chenier [shown at right] because I had done the

role onstage. It was very well prepared. We had the coach who

had worked with us there every day there was a recording session. I

learned an awful lot. I also enjoyed going to Dresden to be a Valkerie

in Maestro Janowski’s

recording of Die Walküre.

The orchestra is incredible, and it was nice to be singing with such a lovely

group of young singers.

To read my Interview with Susan Graham, click HERE. To read my Interview with William Christie, click HERE.

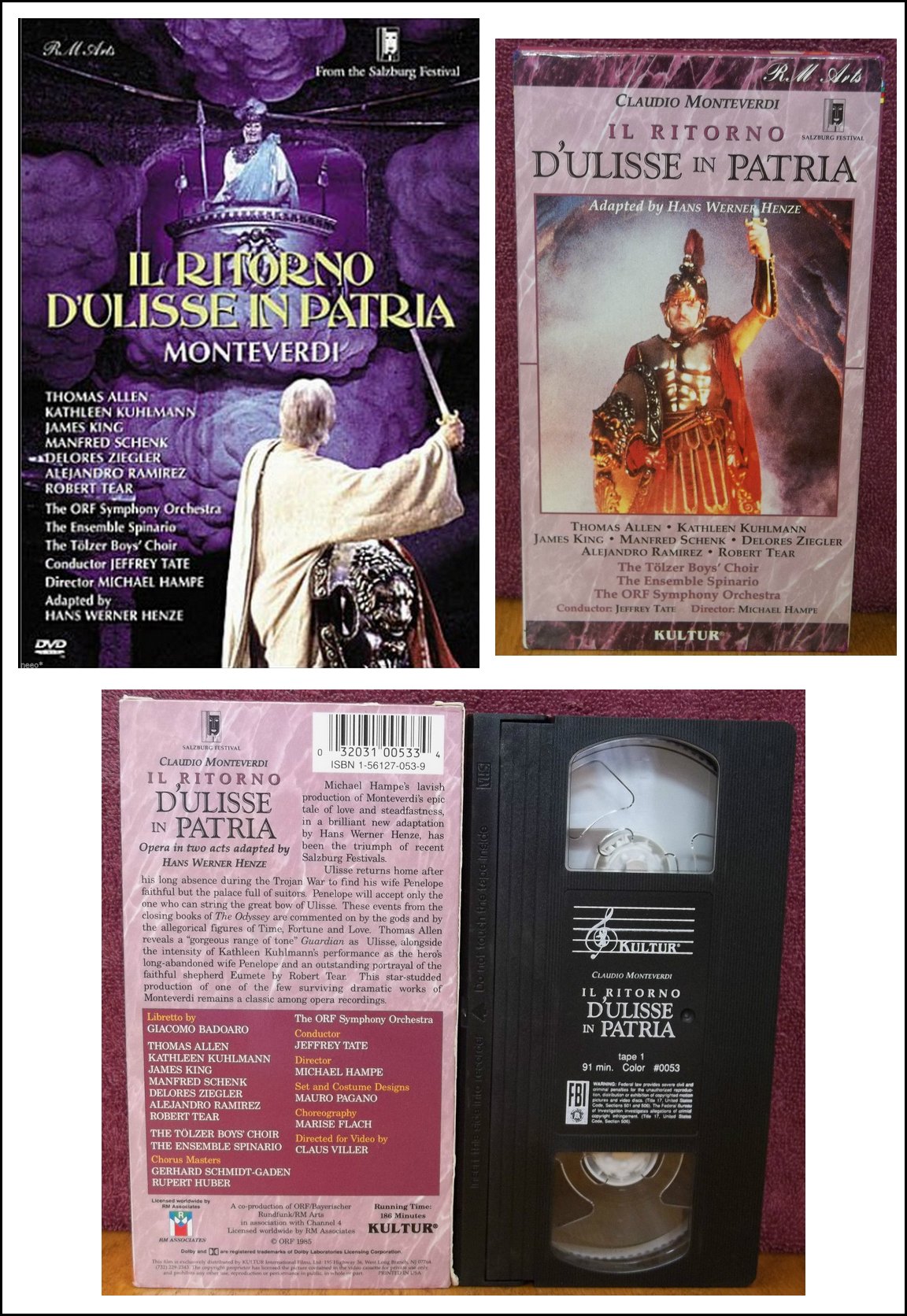

To read my Interview with Thomas Allen, click HERE. To read my Interview with James King, click HERE. To read my Interview with Jeffrey Tate, click HERE. To read my Interview with Hans Werner Henze, click HERE.

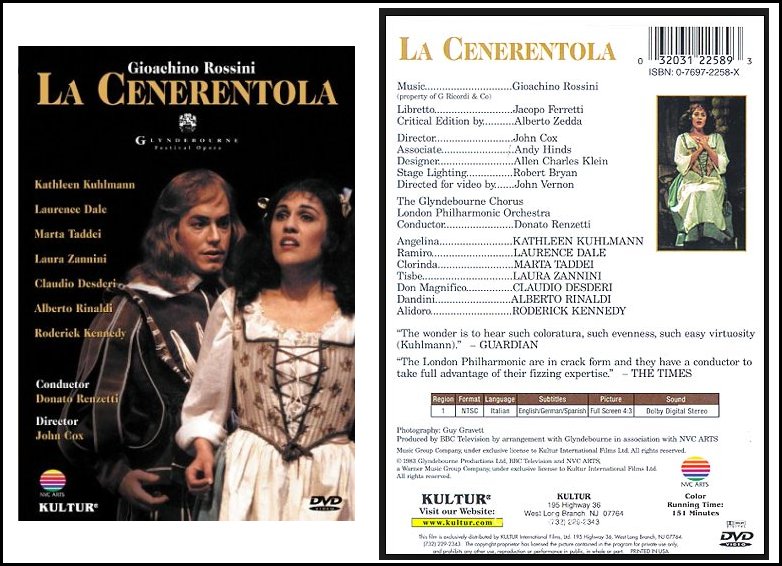

To read my Interview with Laurence dale, click HERE. To read my Interview with Donato Renzetti, click HERE. To read my Interview with John Cox, click HERE. |

© 1984 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago, on December 8, 1984.

The transcription was made and much of it was published in the Massenet Newsletter in January, 1987.

The entire conversation was slightly re-edited, photos and links were added,

and it was posted on this website at the very end of 2015.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.