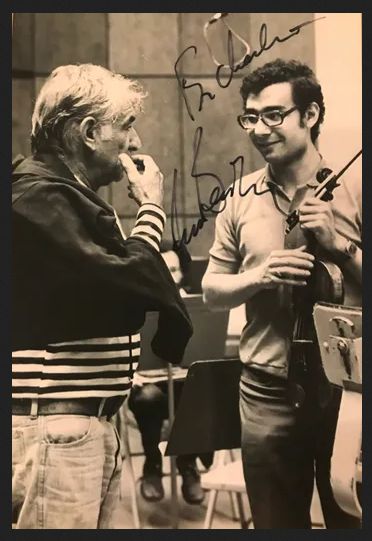

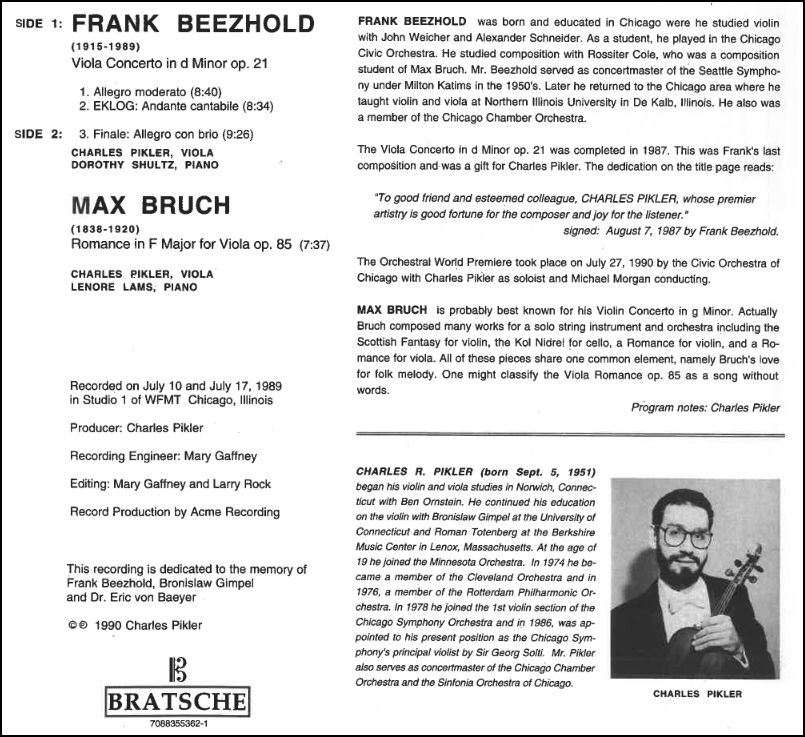

| Charles Pikler joined the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra as a first violinist and, in 1986, he was named principal violist.

Upon his retirement in October 2017, he received the Theodore Thomas Medallion

for Distinguished Service. Pikler studied the piano with his parents and violin with Ben Ornstein, Bronislaw Gimpel at the University of Connecticut and Roman Totenberg at the Tanglewood Young Artist Program at the Berkshire Music Center. While a student, he appeared as soloist with the Hartford Symphony Orchestra, Eastern Connecticut Symphony and Manchester Civic Orchestra (CT), among others. In addition, he earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in Mathematics with Honors from the University of Minnesota.  He launched his musical career as a violinist with the Minnesota

Orchestra in 1971, later becoming a member of the Cleveland Orchestra

(1974 to 1976) and the Rotterdam Philharmonic (1976 to 1978). In 1978,

at the invitation of Sir

Georg Solti, Mr. Pikler became a member of the first violin section

of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Following the retirement of the longtime

principal violist Milton Preves, Pikler was named his successor in 1986,

as the Prince Charitable Trust Chair, eventually becoming the Paul Hindemith

Principal Viola Endowed Chair. [Photo at left with Leonard Bernstein.]

He launched his musical career as a violinist with the Minnesota

Orchestra in 1971, later becoming a member of the Cleveland Orchestra

(1974 to 1976) and the Rotterdam Philharmonic (1976 to 1978). In 1978,

at the invitation of Sir

Georg Solti, Mr. Pikler became a member of the first violin section

of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Following the retirement of the longtime

principal violist Milton Preves, Pikler was named his successor in 1986,

as the Prince Charitable Trust Chair, eventually becoming the Paul Hindemith

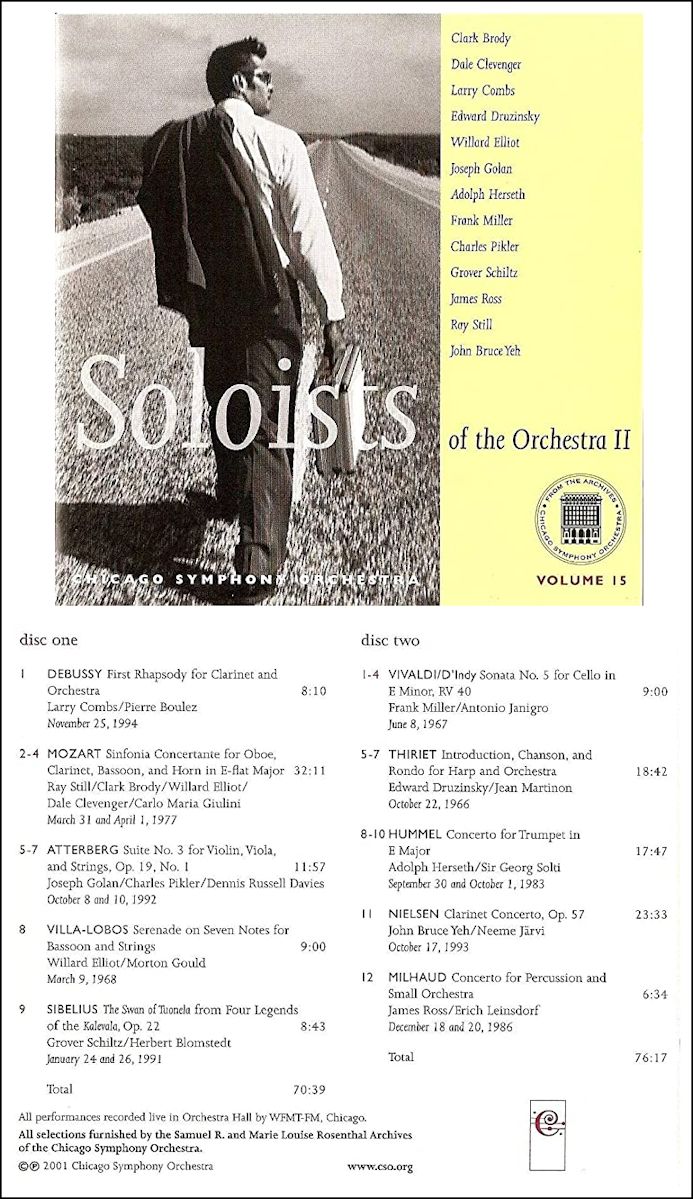

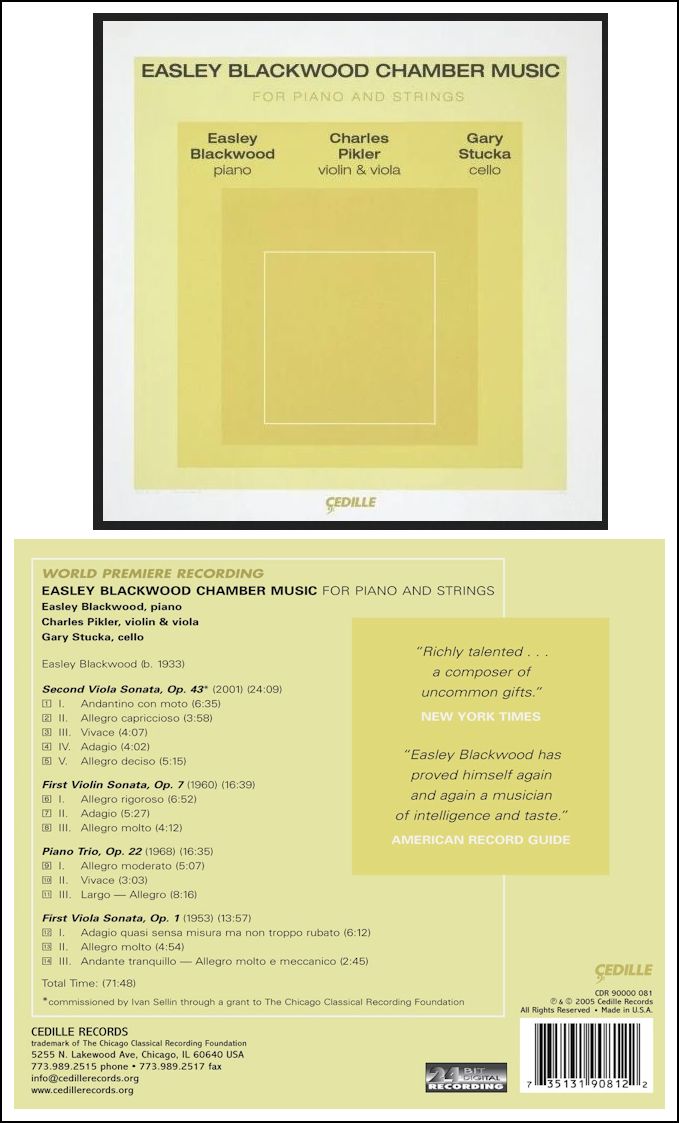

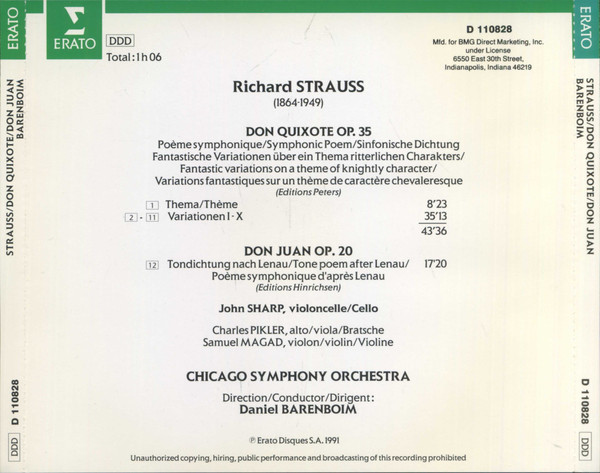

Principal Viola Endowed Chair. [Photo at left with Leonard Bernstein.]Pikler has been featured as a soloist with the CSO under Sir Georg Solti and Daniel Barenboim, as well as with other titled and guest conductors such as Sir Andrew Davis, Pierre Boulez, Harry Bicket, Charles Dutoit, Sir Mark Elder, Dennis Russell Davies, Asher Fisch, Nicholas McGegan, and James Levine. Additionally, he has also been soloist with the Kingsport Tennessee Symphony, Orchestra of the Pines in Nacogdoches, Texas, National Symphony Orchestra of Costa Rica and National Taiwan Symphony Orchestra. Pikler served as concertmaster of the Chicago Chamber Orchestra under Dieter Kober, touring with it and also performing as soloist on over more than 70 occasions; the Sinfonia Orchestra of Chicago under Barry Faldner; the Orchestra of the Apollo Chorus; the Chicago Opera Theater Orchestra; the Northbrook Symphony under Samuel Magad and Lawrence Rapchak; and the Symphony of Oak Park and River Forest under Jay Friedman. He served as principal violist of the Ars Viva Symphony Orchestra under Alan Heatherington. In addition, he was principal viola of the Ravinia Festival Orchestra and guest conducted the Chicago Chamber Orchestra several times. A chamber music enthusiast, he has performed with several ensembles, including the Chicago Symphony String Quartet and the Tononi Ensemble with pianist Susan Merdinger. Pikler has been a guest artist with the Daniel String Quartet in Holland, the Vermeer Quartet of De Kalb, and the Louisville String Quartet. In 1990, he performed Frank Beezhold’s Viola Concerto, which was composed for and dedicated to him, with the Civic Orchestra of Chicago at Orchestra Hall. He also has recorded it in the composer’s own transcription for piano and viola with Dorothy Shultz. He has recorded Easley Blackwood’s chamber music with the composer for Cedille Records. He was featured as soloist on the Sewanee Symphony’s 2003 recording of Berlioz’s Harold in Italy for Solo Viola and Orchestra, with Victor Yampolsky conducting. In 1995 and 1996, he served as guest principal violist for the Boston Symphony under Seiji Ozawa and was a guest violist at the Bay Chamber Concerts in Rockland, Maine. Pikler participates in the Grand Teton Music Festival in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. While on sabbatical from the CSO during the 2014–15 season, Pikler performed as a substitute section violist at the Lyric Opera of Chicago for two operas by Strauss and Wagner. Mr. Pikler served on the faculty of Northwestern University, North Park University, Northeastern Illinois University, Wheaton College and the American Conservatory of Music. He coached the violists of the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, as well as other ensembles at the Midwest Young Artists program in Highwood, Illinois. Pikler is the founder and music director of I Solisti, a chamber orchestra which is part of the Midwest Young Artists program. Pikler has taught or given Master Classes at prestigious universities, conservatories and music festivals such as Eastman School of Music, University of Missouri - Kansas City, Sewanee Music Festival, and others. Pikler and his wife, Ruth, have two sons, David, a Math teacher in Houston's prestigious Village School, and Andrew, a software engineer in Tel Aviv, Israel, and a daughter, Amy, a violist with the San Antonio Symphony and soon to be member of the Utah Symphony. During retirement, Pikler is completing a massive archival recording project he started in 1999, namely a remastering of the recordings of his late professor Bronislaw Gimpel. == Biography and photo from Pickler’s official

website.

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

BD: Then you also

recorded it in a version for piano?

BD: Then you also

recorded it in a version for piano?© 2003 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in a rehearsal room backstage at Orchestra Hall, Chicago, on May 15, 2003. Portions were broadcast on WNUR in 2005 and 2013, and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2005 and 2008. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.