| The American counter-tenor, Derek Lee Ragin,

was born June 18, 1958 in West Point, New York and raised in Newark, New

Jersey. He first studied the piano, and went on to begin his formal vocal

training at the Newark Boys Chorus School. He later attended the Oberlin

College Conservatory of Music, where he majored in piano and music education.

He was first place winner in the 1983 Purcell-Britten Prize for Concert

Singers in England, the Prix Spécial du Jury du Grand Prix Lyrique

de Monte Carlo in 1988, and in 1986 the First Prize at the 35th

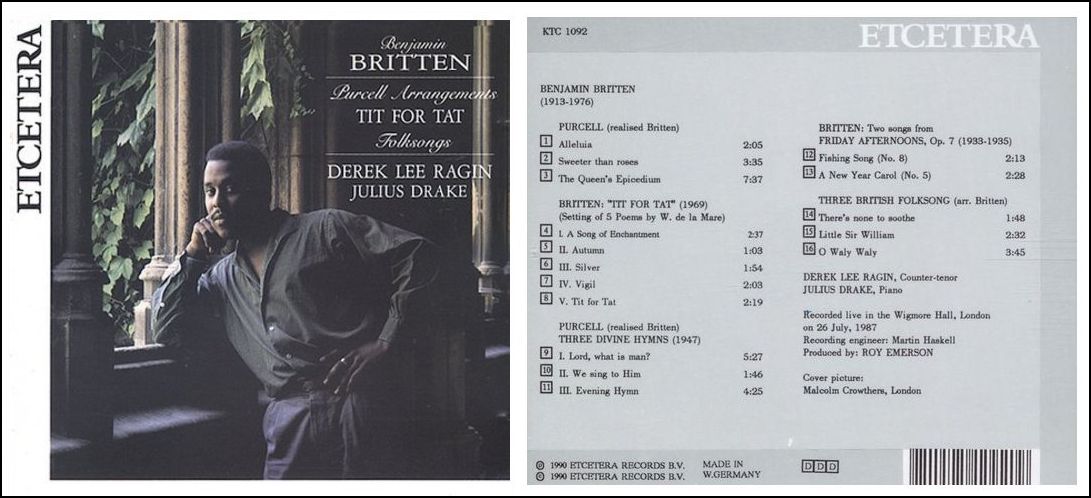

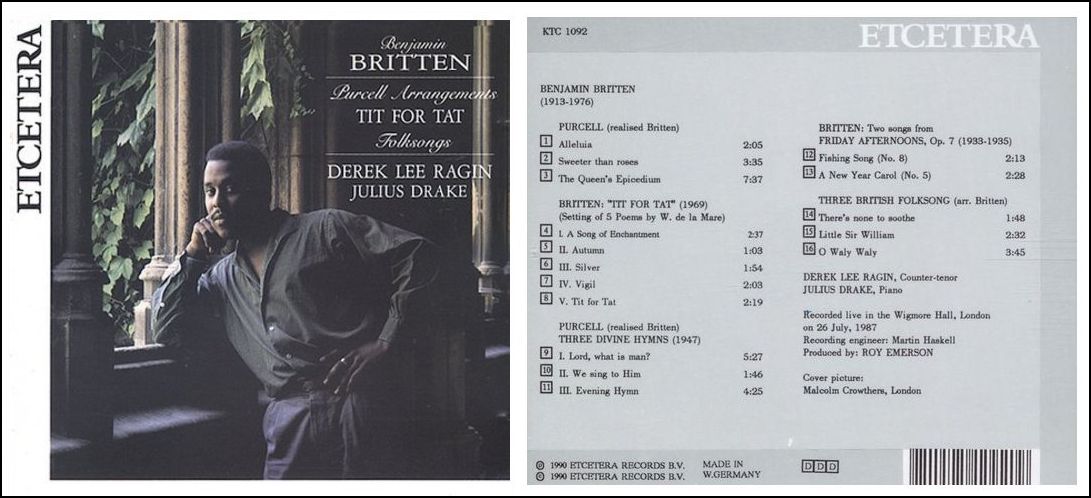

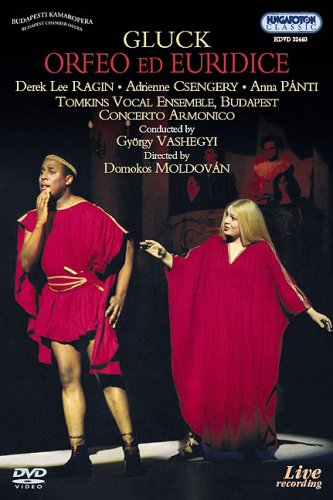

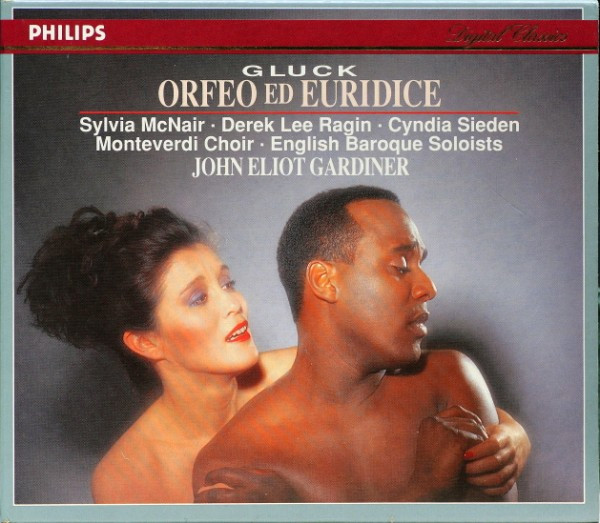

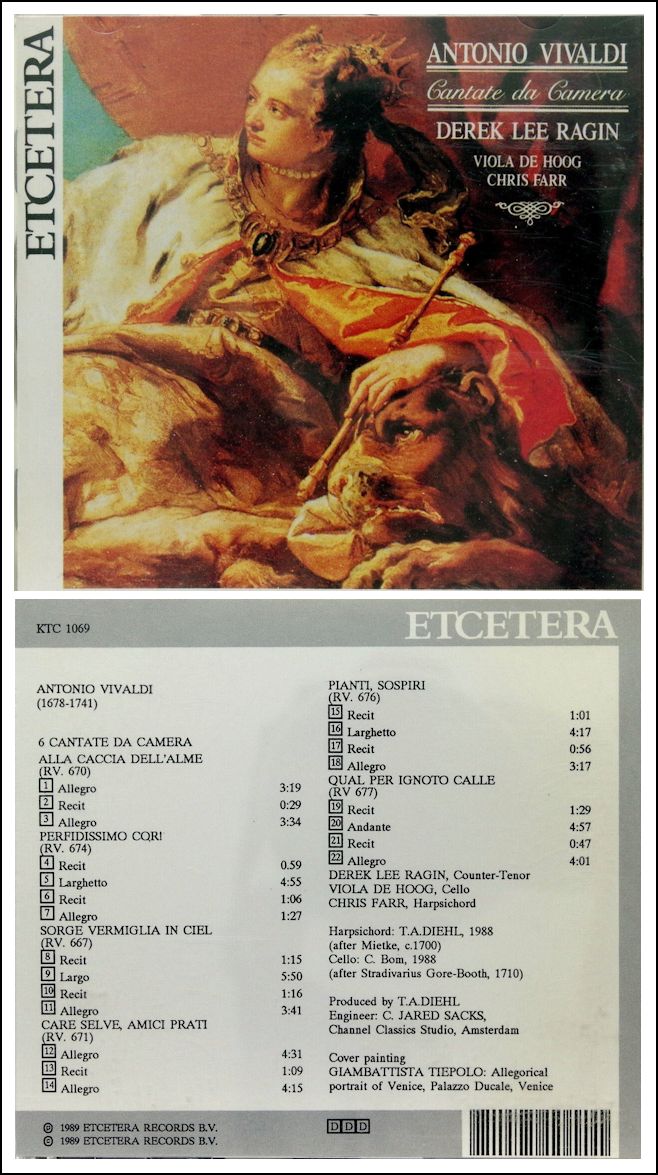

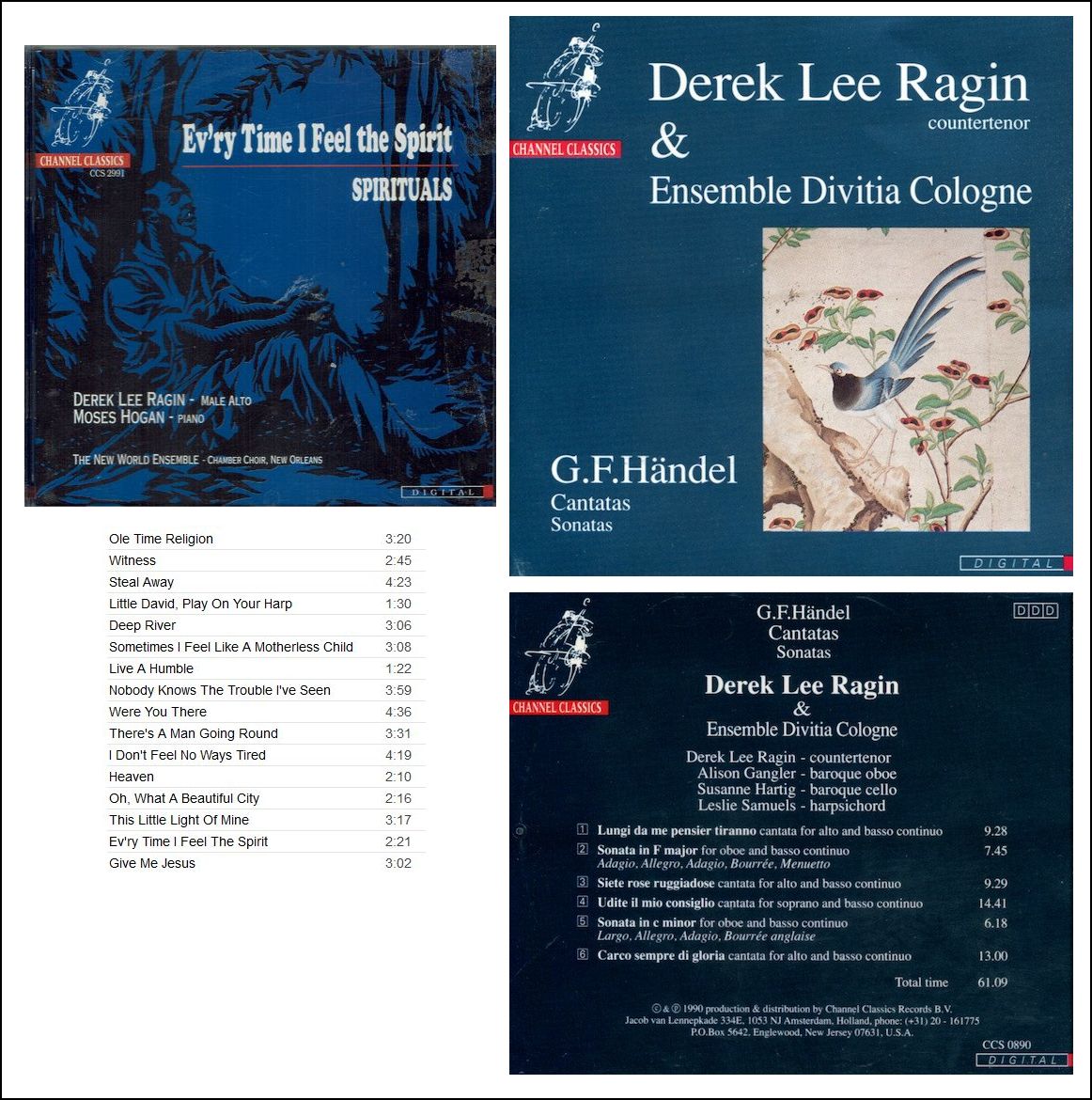

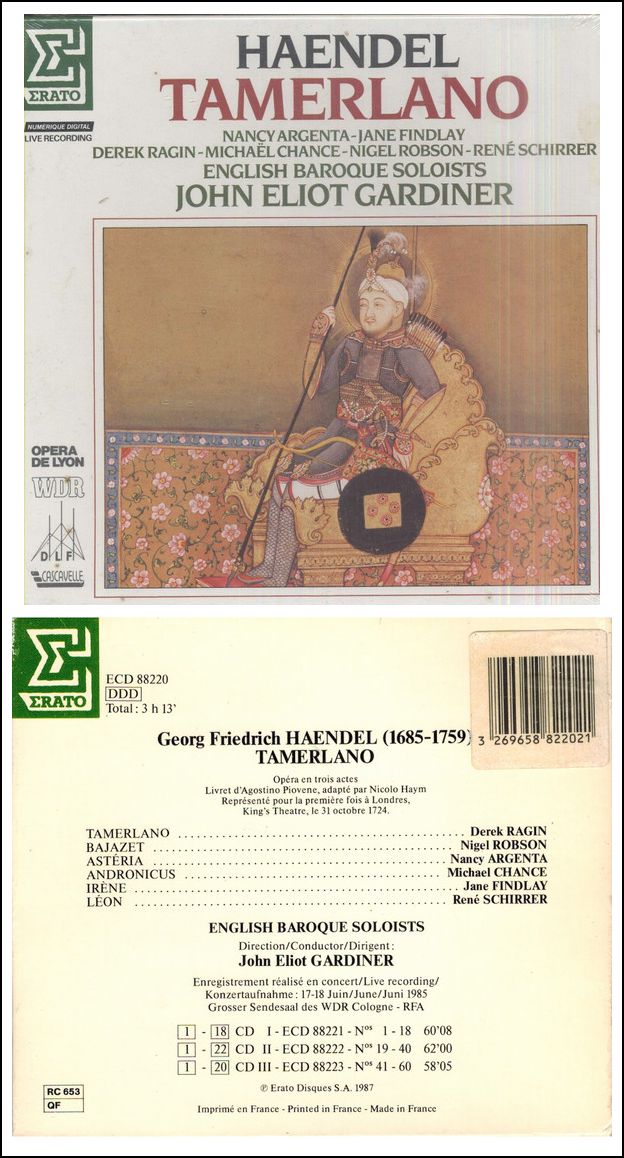

International Music Competition in Munich. With a swiftly moving career, Derek Lee Ragin made a series of highly acclaimed debuts, notably at the Metropolitan Opera in 1988 in George Frideric Handel's Giulio Cesare; in recital at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1991, and at the Salzburg Festival in Gluck's Orfeo with the Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra in 1990. He made his London recital debut at Wigmore Hall in 1984, and was immediately re-engaged for the following year. Derek Lee Ragin is regarded as one of the foremost counter-tenors of our day. In great demand as a master of Baroque vocal style, he is also an inspired interpreter of contemporary music. He has performed throughout North America and Europe, including recitals at Wigmore Hall and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. His performances of such diverse repertoire are characterized by an unusual warmth and expressivity. He has received unanimous accolades from critics and audiences throughout the world. He has been described as "a rare performer who sets a new standard," [Financial Times of London] and "A soloist who simply overwhelms the audience," [Cleveland Plain Dealer]. Derek Lee Ragin sang in Leonard Bernstein's Chichester Psalms at Tanglewood with Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He has appeared at the Schleswig-Holstein Festival and at Salzburg in Györgi Ligeti's 1978 opera Le Grand Macabre, conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen and directed by Peter Sellars. The production was also presented in Paris at the Théâtre du Châtelet. He appeared in recital at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; sang the role of Arsamenes in G.F. Handel's Xerxes at the Seattle Opera, and in a return engagement at the Metropolitan Opera, sang the role of Oberon in Benjamin Britten's A Midsummer Night's Dream. He has worked with many of the world's great conductors, including Leonard Bernstein, William Christie, Péter Eötvös, Christoph Eschenbach, Sir John Eliot Gardiner, René Jacobs, Kurt Masur, Seiji Ozawa, Helmuth Rilling, Esa-Pekka Salonen, and Robert Spano, among others. In recent seasons, Derek Lee Ragin sang the 1739 (first performance) version of G.F. Handel's Israel in Egypt in Budapest, debuted Enjott Schneider's Der Name der Rose, written specifically for Ragin, and appeared in the world premiere of Jonathan Dawe's Prometheus at the Guggenheim Museum. He appeared in the Munich Opera's production of Rinaldo, toured Austria and Germany with the Vienna Konzertverein, and toured with the Baroque ensemble Florilegium in Israel, Germany, France and Spain. Recent USA appearances include a tour with the Baroque ensemble Rebel, G.F. Handel's Messiah in Cleveland with Appolo’s Fire, a collaboration with The Aulos Ensemble in a Christmas program at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and appearances in San Francisco with the American Bach Soloists. Other highlights include the New York Philharmonic Orchestra world premiere of Kancheli's And Farewell Goes Out Sighing... [shown above, and a recording of another Kancheli work is shown at the end of our interview, near the bottom of this webpage]; performances of J.S. Bach's St. John Passion (BWV 245) with the London Philharmonic Orchestra; Gluck's Orfeo ed Eurydice in Vienna and at the Rheingau Music Festival; and Kancheli's Diplipito with the Stuttgarter Kammerorchester at the Lucerne Festival and again in Stuttgart when the work was recorded for ECM. Derek Lee Ragin sang Belize and several other roles in the world premiere of Péter Eötvös' Angels in America at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. He performed G.F. Handel's Alexander Balus in St. Paul, Minnesota; concerts with the Kölner Kammerorchester in Cologne and Munich; and Bach cantatas with the Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra in Milan and London which were recorded for Deutsche Grammophon. Other engagements include performances of Messiah with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra and Louisville Bach Society; and the role of Anfinomus in Monteverdi's Il Ritorno d'Ulisse in Patria with the Netherlands Opera in Sydney. Derek Lee Ragin has recorded for the Telarc, Philips, EMI, Erato and Capriccio labels. His discography includes Italian lute songs, G.F. Handel cantatas, and a disc of spirituals entitled Ev'ry Time I Feel the Spirit, all for Channel Classics. He recorded the role of Orfeo in Orfeo ed Euridice for Philips Classical, the title role in G.F. Handel's Tamerlano, and Teseo for Erato, and the role of Poro in the world premiere recording of Johann Adolf Hasse's Cleofide on the Capriccio label. With the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Robert Shaw, he performed and recorded Leonard Bernstein's Chichester Psalms and the world premiere of the composer's Missa Brevis. The recording subsequently won a Grammy Award, and his recording of Giulio Cesare with Concerto Köln received a Gramophone Award in 1992. He also lent his voice to Farinelli, a film about the famed 18th century castrato which won the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Film in 1995. The soundtrack won the Golden Record award the following year in Cannes. [Many of these recordings are shown later on this webpage.] == Biography from the Bach Cantatas website.

[Text only - photo is from another source]

== Names which are links in this box and below refer

to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

|

The history of Community Concerts parallels in many ways that of the past century. During the 1920s, radio, film, and the phonograph gave millions of Americans their first taste of professional-quality performing arts. There was a problem, though. This problem was that while America’s interest in great, live music was growing, the audiences to support such concerts were largely confined to major cities, while hundreds more cities had no concerts at all, for it was too risky a business. It would be up to some group like the local ladies’ musical club to try to bring some noted musical artist or group to their city, which first meant lining up some deep pockets to underwrite the cost. Guarantors too often got stuck with meeting a deficit when attendance might rise or fall depending on the public’s whims, the weather, or competition from other local events. Community Concerts proved to be the solution to this problem. Community Concerts started on a shoe-string budget in Chicago in 1920, the brainchild of two music managers, Dema Harshbarger and Ward French. It was an idea born of desperation. They were faced with declining concert dates for their artists as both small towns and larger cities were cutting back on concert presentations. The idea that French and his associate came up with was disarmingly simple. They proposed to do away with such local financial risk by organizing a permanent concert association on a non-profit membership basis, raising funds through an intensive one-week campaign. Once the money was raised, artists would be engaged within the limits of the available funds. Sale of single admissions would be done away with — only members could attend the concerts. Thus was born the organized membership concert audience movement. The idea blossomed and fostered cultural development on an unprecedented scale. Families who had been indifferent to “highbrow” single concerts were attracted to a whole season with varied offerings at a reasonable price. A new appreciation for the performing arts, deeply rooted in community spirit, steadily developed across North America, contributing to the growth of local symphonies, theatres, and dance companies. The first year saw the new idea planted in 12 cities, and by the end of the second year 40 cities in the Middle West had organized membership concert audiences. By 1928, the movement was organized in New York City as the Community Concert Association, with French as its president. In 1930 the nation’s leading artist management organizations, Columbia Artists Management, Inc. and National Artist Service (representing a majority of the established musical artists and attractions) put the weight of their artistic and financial support behind Community Concerts. Despite the ravages of the Great Depression in those years, the organized concert membership movement rapidly expanded as artists could depend upon a network of cities with money in the bank to pay for the season’s concerts even before contracts were signed. This meant their fees could be lowered as concert tours were expanded, and the organized audience movement became a significant new artistic and cultural development for the nation. As the nation emerged from the traumas of the Depression and World War II, Community Concerts expanded rapidly. Concert Associations were formed in Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, and even, briefly, South Africa. In 1993, Community Concerts restructured its relationship with Columbia

Artists Management, Inc., its longtime parent company, and was free to feature

artists outside the CAMI roster and make its own artistic decisions. In

1999, Trawick Artists Management purchased the company and continued to

provide national leadership until its demise in 2002. The 2002-2003 season

was the first that local Community Concert Associations operated independently

of any national organization. There are several new national organizations

that will provide the services that Trawick provided if the local Community

Concert Associations wishes to join them. == From the Tehama County Community Concert Association, Red Bluff, California |

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 23, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later, and again in 1998. This transcription was made at the end of 2022, and posted on this website early in 2023. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.