|

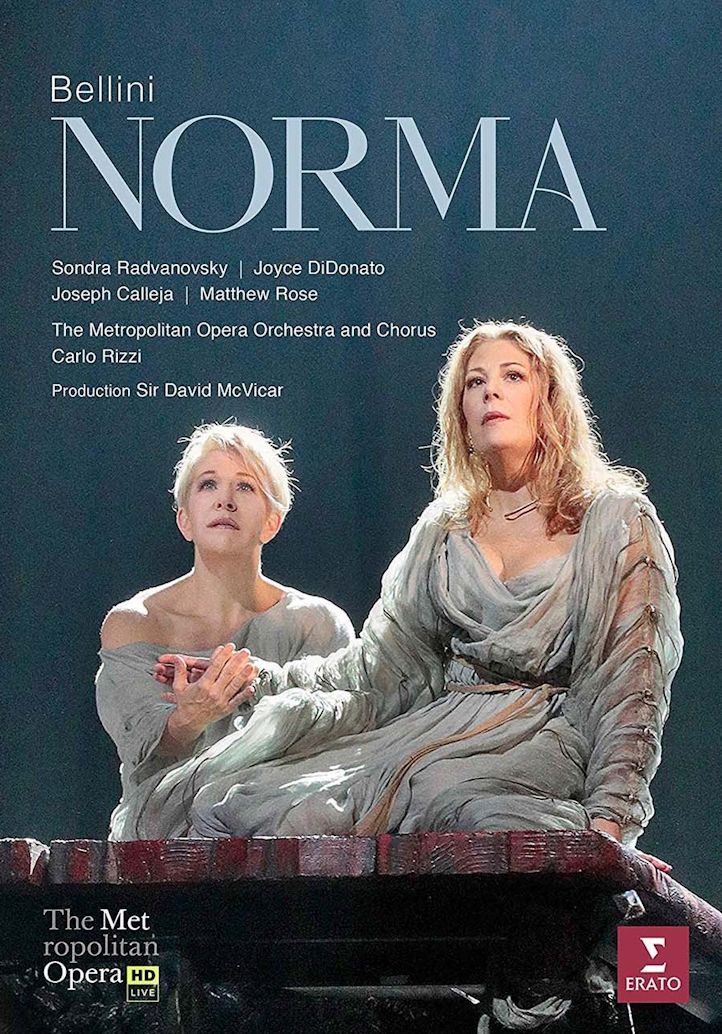

Carlo Rizzi holds a long-standing reputation as one of the world’s foremost operatic conductors, in demand as a guest artist at the world’s most prestigious venues and festivals. Equally at home in the opera house and the concert hall, his vast repertoire spans everything from the foundation works of the operatic and symphonic canon to rarities by Bellini, Cimarosa and Donizetti to Giordano, Pizzetti and Montemezzi. Combining a deep expertise in the vocal art with theatrical flair and the practical collaborative skills honed over decades of experience in the world’s finest theatres, he is acclaimed by singers and audiences alike as a master of the operatic craft. Born in Milan, Rizzi studied at the city’s conservatoire, and following his graduation was employed as a repetiteur at the legendary Teatro alla Scala. He launched his conducting career in 1982 with a production of Donizetti’s L’ajo nell’imbarazzo, and has now performed over a hundred operas, with a broad repertoire that is rich in Italian works in addition to the major titles of Mozart, Wagner, Strauss, Britten, Mussorgsky, Martinů and Janáček. In September 2019 he was appointed Music Director of Opera Rara, the UK-based company devoted to resurrecting and returning to the repertoire undiscovered and undervalued works from opera’s celebrated and neglected composers. Following 2022’s new recording of Mercadante’s Il Proscritto, the position was extended until 2025, and future seasons will see performances and recordings of rarities by Donizetti and Halevy. Since 2015, Rizzi has been Conductor Laureate of the Welsh National Opera, following his tenure as Music Director (1992-2001 and 2004-8) during which he was widely credited with overseeing a dramatic increase in the company’s artistic standards and international profile. He also has held long-standing relationships with the Teatro alla Scala, the Royal Opera House Covent Garden and the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and his career has seen him leading numerous productions at the most distinguished operatic addresses including the Opera National de Paris, Teatro Real Madrid, the Rossini Opera Festival of Pesaro, the Netherlands Opera, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, the New National Theatre Tokyo, Opernhaus Zürich, Deutsche Oper Berlin and the Théâtre Royal de La Monnaie, Brussels. Rizzi is also critically acclaimed as a symphonic conductor with distinguished orchestras around the world including Halle, the London Philharmonic, the Filarmonica della Scala, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, the Netherlands Philharmonic, Orchestra i Pomeriggi Musicali, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, Bergen Philharmonic, Hungarian National Philharmonic, Orquestra Simfònica de Barcelona i Nacional de Catalunya, Hong Kong Philharmonic, Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg, Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, and the orchestra of the National Arts Centre, Ottawa. Rizzi’s recent highlights include opening the Canadian Opera Company’s 19/20 season with a new production of Turandot, his debut with the Teatro del Maggio Musicale Firenze, in performances of Un Ballo in Maschera and La Traviata, his debut at the Palau de les Arts in Valencia for La Cenerentola, concert performances with the Halle and the Antwerp Symphony, new productions of Les Vepres Siciliennes for Welsh National Opera and Zandonai’s Francesca da Rimini for Deutsche Oper Berlin, and his debut at the Norwegian Opera in Oslo in a new production of Rigoletto. In the 21/22 season he opens the Welsh National Opera season with a production of Madama Butterfly, conducts symphonic concerts with the Orquestra Sinfónica do Porto Casa da Música, and also returns to the Metropolitan Opera with productions of Tosca and La Bohème; and to the Bayerische Staatsoper with a production of Tosca. Carlo Rizzi’s extensive discography includes complete recordings

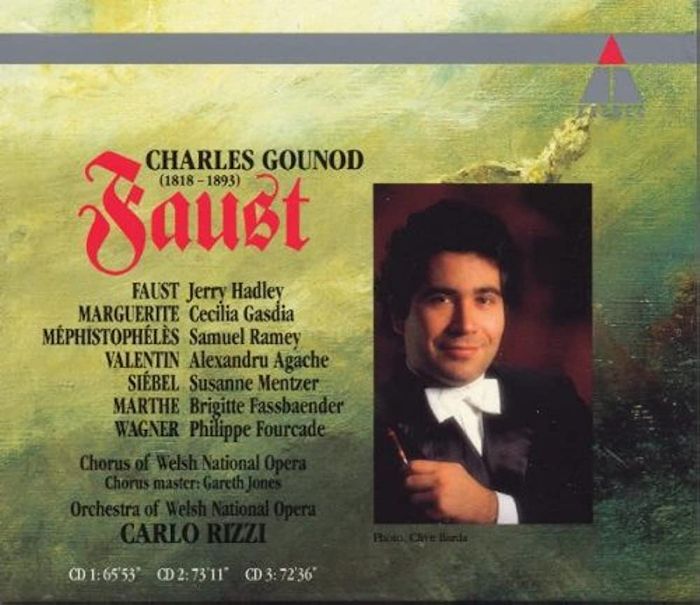

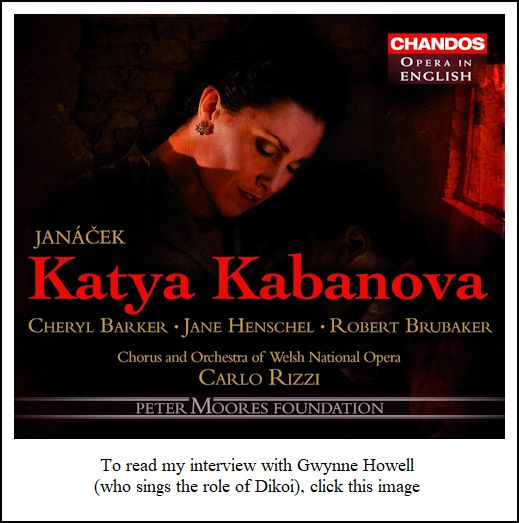

of Gounod’s Faust, Janáček’s Katya Kabanova (in English)

and Verdi’s Rigoletto and Un ballo in maschera, all with

Welsh National Opera; a Deutsche Grammophon DVD and CD of Verdi’s La

Traviata recorded live at the Salzburg Festival with Anna Netrebko,

Rolando Villazon and the Vienna Philharmonic; numerous recital albums with

renowned opera singers including Joseph Calleja, Juan Diego Florez, Edita

Gruberova, Jennifer Larmore,

Ernesto Palacio, Olga Borodina and Thomas Hampson, and most

recently a pair of Gramophone Award-nominated discs for Opera Rara with

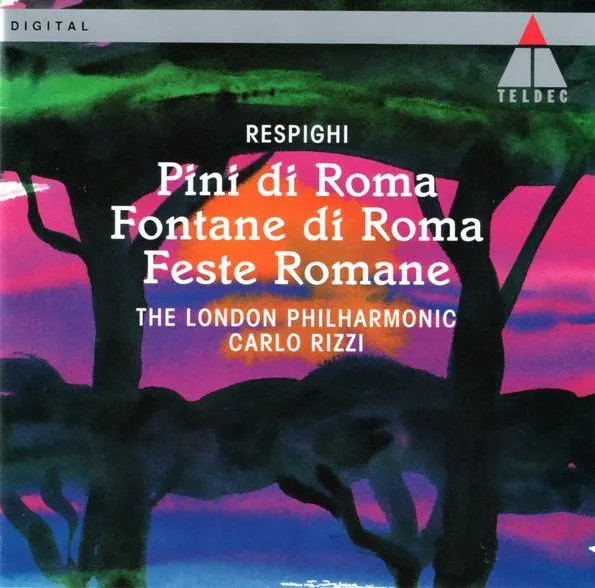

Joyce El-Khoury and Michael Spyres. He has also made recordings of symphonic

works by Bizet, de Falla, Ravel, Respighi and Schubert with orchestras

including the London and Netherlands Philharmonics. == Biography from the IMG Artists website |

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in suburban Chicago on July 29, 1993. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1995 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.