See my interviews with Bright Sheng, and Hugo Weisgall

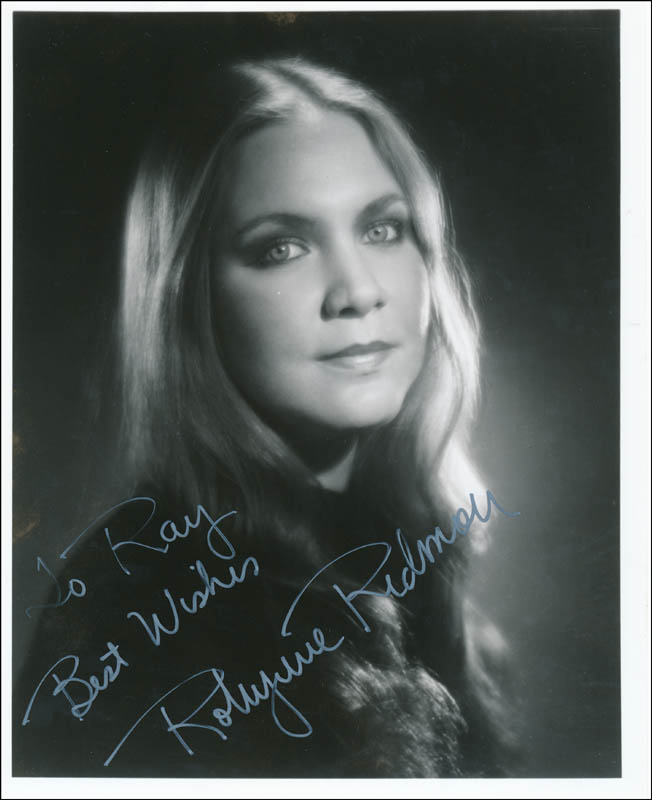

Robynne Redmon at Lyric Opera of Chicago

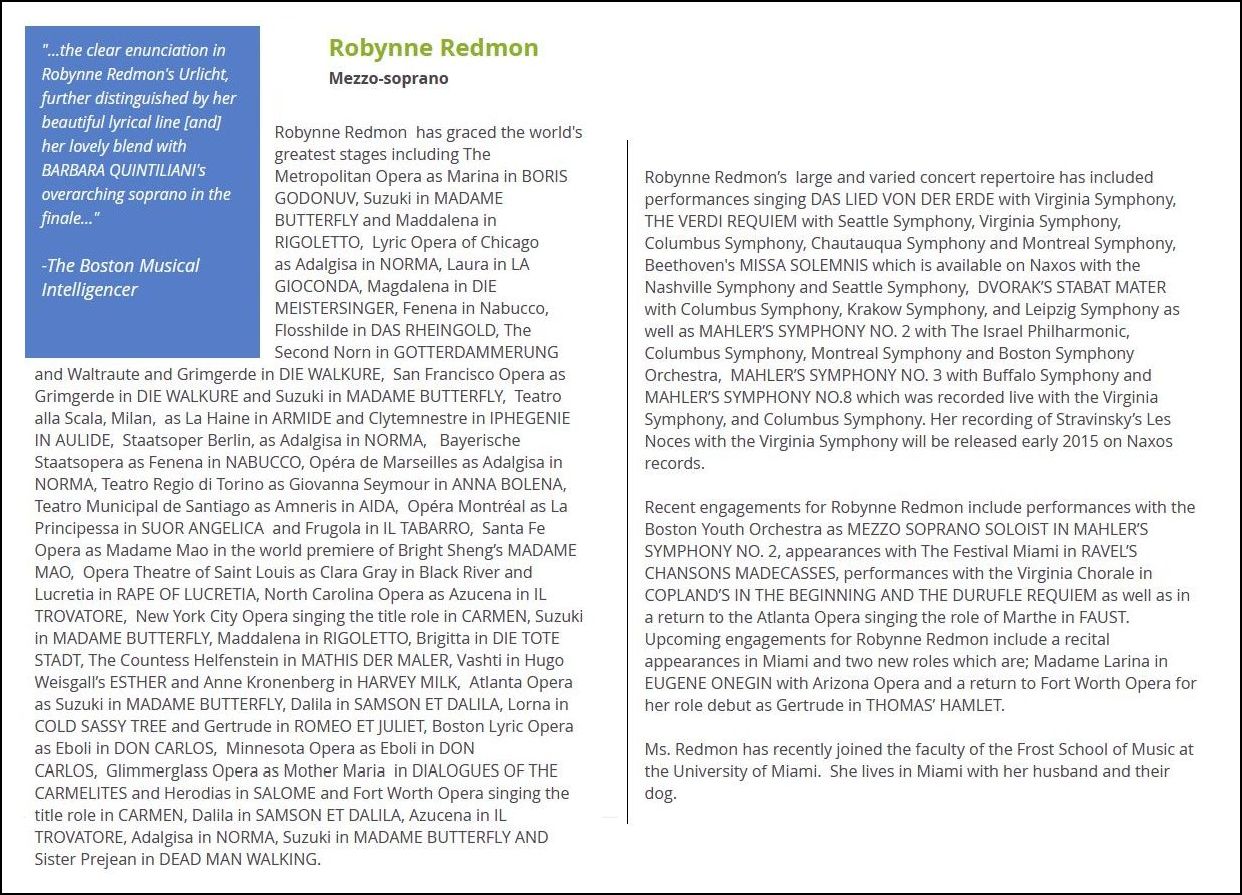

1983 Aïda [Opening Night] (Priestess), with Tomowa-Sintow, Pavarotti/Giacomini, Cossotto, Wixell, Giaotti, Kavrakos, Negrini; Bartoletti, Joël, Halmen Manon (Rosette), with Scotto, Kraus, Titus, Washington, Castel; Rudel, Hebert, Dupont 1984 Carmen (Mercédès), with Nafé/Berganza, Domingo/Frusoni, Studer, Devlin; Plasson, Ponnelle Frau ohne schatten (Child's voice), with Marton, Johns, Nimsgern, Zschau, Dunn; Janowski, Corsaro, Chase 1985-86 Otello [Opening Night] (Emilia), with Domingo/Johns, Price, Milnes, McCauley/Kunde; Bartoletti, Diaz, Pizzi Traviata (Annina), with Malfitano, Araiza, Elvira; Bartoletti, Alden, Pizzi Rondine (Suzy), with Cotrubas, Kunde, Stone, Langton, Doss, Kaasch; Bartoletti, Chazalettes, Santicchi 1986-87 Parsifal (Flower Maiden), with Vickers, Troyanos, Sotin/Howell, Nimsgern, Becht, Salminen/Kennedy; Perick, Pizzi 1988-89 Tancredi (Isaura), with Horne, Cuberli, Merritt, Cox, Sharon Graham; Bartoletti, Copley, Conklin 1990-91 Rigoletto (Maddalena), with Nucci, Pace, Araiza, Langan; Fiore, Sequi, Pizzi, Tallchief, Schuler 1992-93 Rheingold (Flosshilde), with Morris, Troyanos, Wlaschiha, McCauley, Maultsby, Terfel (Donner); Mehta, Everding, Conklin 1995-96 Andrea Chénier (Madelon), with Jóhannsson, Millo/Fantini, Leiferkus; Bartoletti, Mansouri, Williams, Schuler, Dufford Ring - Rheingold (Flosshilde), with Morris, Lipovšek, Wlaschiha, Clark, Maultsby, Held; (same as above) - Walküre (Grimgerde), with Marton/Eaglen, Morris, Elming, Kiberg, Lipovšek, Salminen; (same as above) - Götterdämmerung (Second Norn & Flosshilde), with Marton/Eaglen, Jerusalem, Salminen, Held, Lipovšek, Byrne, Wlaschiha; (same) 1996-97 Norma (Adalgisa), with Anderson, Margison, Colombara; Rizzi, Graham, Conklin 1997-98 Nabucco [Opening Night] (Fenena), with Agache, Guleghina, Denniston, Ramey; Bartoletti, Moshinsky, Yeargan 1998-99 Gioconda [Opening Night] (Laura), with Eaglen, Botha, Putilin, Halfvarson, Maultsby; Bartoletti, Copley, Brown, Tallchief Meistersinger (Magdalena), with Rootering, Gustafson, Winbergh, Pape, Schulte, Schade, Del Carlo; Thielemann, Horres, Rheinhardt 2004-05 Ring - Walküre (Waltraute), with Morris, Eaglen, Domingo, DeYoung, Diadkova, Halfvarson; Davis, Everding/Kellner, Conklin |

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 10, 1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following week. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.