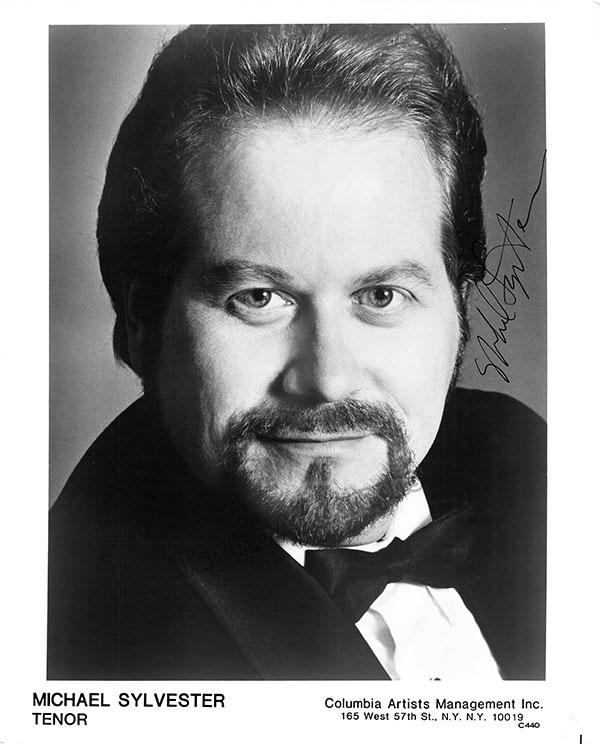

| Tenor Michael Sylvester, widely considered

one of the finest lyric spinto tenors of his

generation before turning his skills to teaching, holds a BM from Westminster

Choir College and a MM from Indiana University. Mr.

Sylvester has sung leading roles in the major

opera houses of the world, including the Metropolitan Opera, London’s

Covent Garden, Milan’s La Scala, Vienna Staatsoper,

Opera Australia’s Sydney Opera House, San Francisco

Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Dallas Opera, Paris Opera, Buenos

Aires’ Teatro Colon, Houston Grand Opera, Venice’s Teatro

La Fenice, Staatsoper Berlin, Grand Theater de Geneva,

Deutsche Oper Berlin, Florence’s Maggio Musicale, Hamburg

Staatsoper, Bonn Staatsoper, Frankfurt Staatsoper, Opera de Toulouse,

the New Israeli Opera, and many others. During the

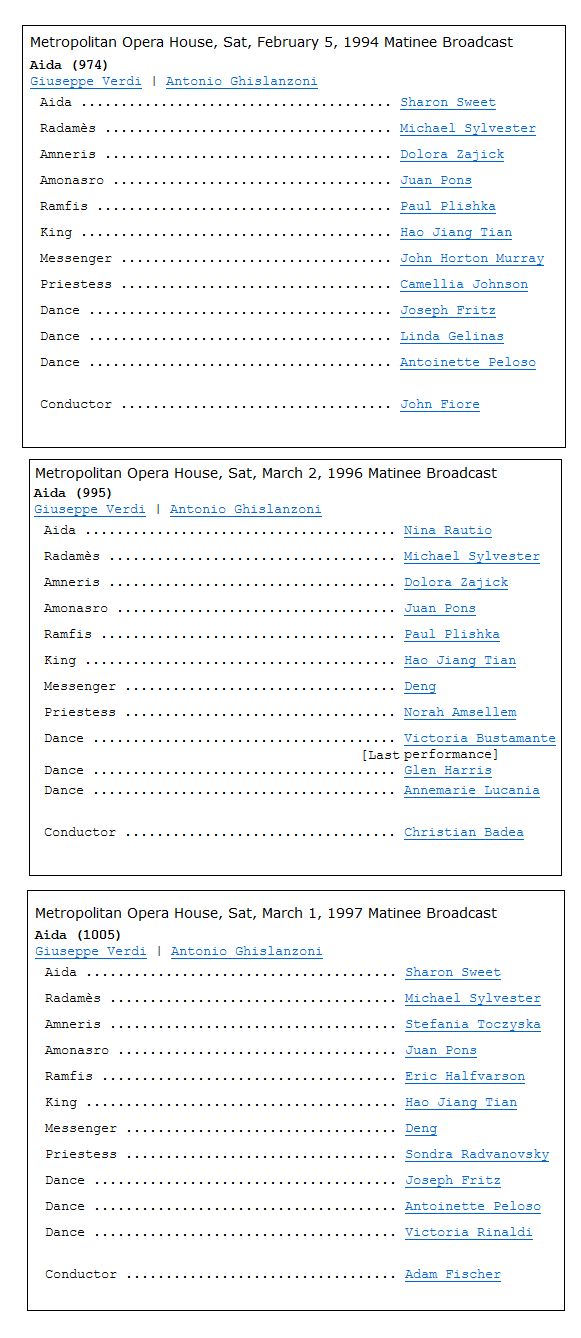

1990s, Mr. Sylvester sang more performances at

the Metropolitan Opera of Radamès in Verdi’s opera AÏDA than

any other tenor. [Of the 27 performances, 3 were Saturday afternoon broadcasts,

and they are shown in a box below-right.] A 1989

article in USA Today named Mr. Sylvester as one of the two

most important tenors of his generation.

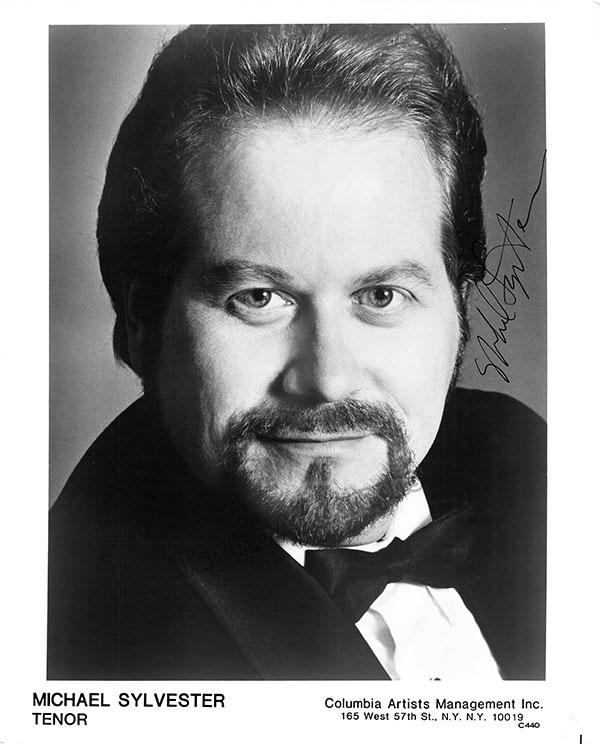

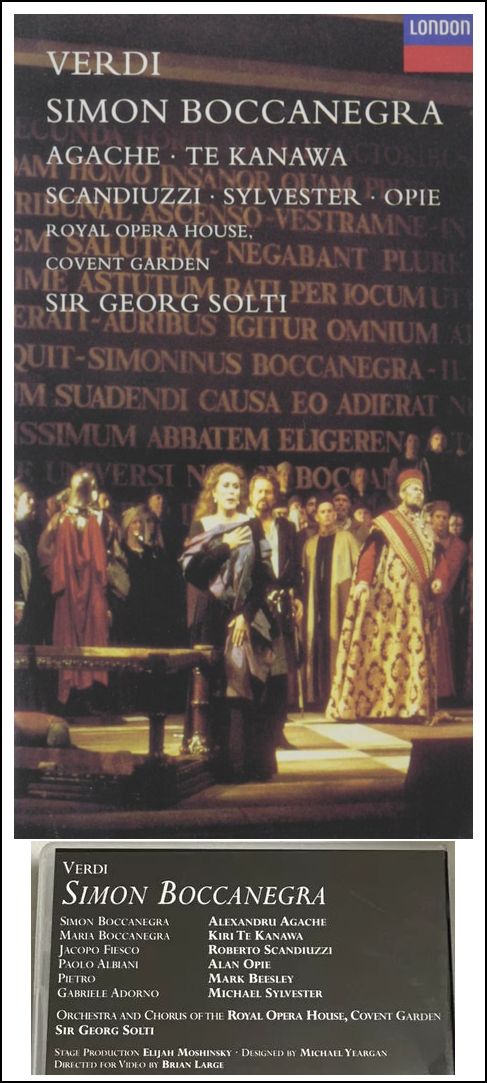

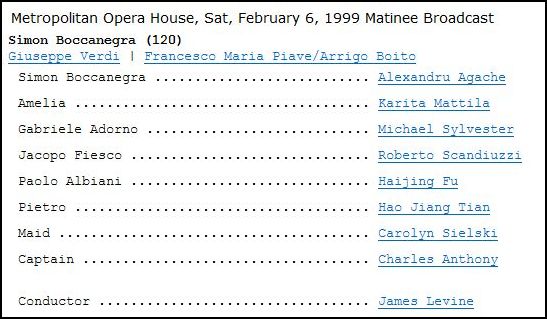

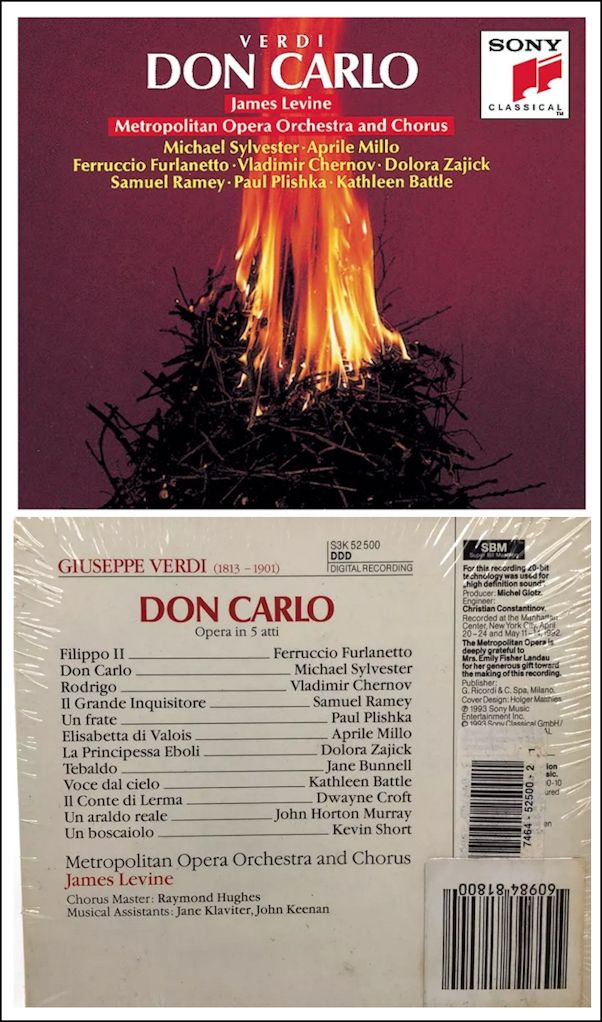

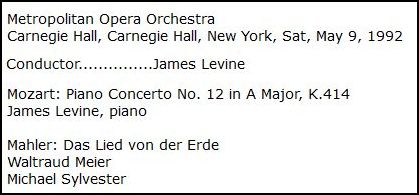

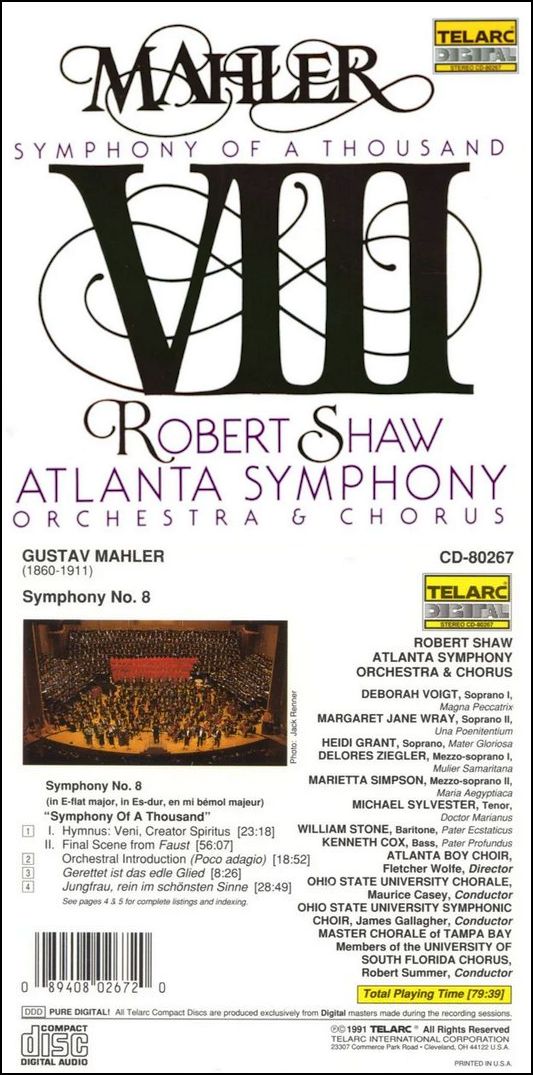

Among others his opera repertoire includes Radamès in AÏDA (which he has sung over 150 times), the title role Don Carlo in DON CARLO, Adorno in SIMON BOCCANEGRA, Cavaradossi in TOSCA, Pinkerton in MADAMA BUTTERFLY, Calaf in TURANDOT, Rodolfo in LA BOHÈME, Bacchus in ARIADNE AUF NAXOS, Der Kaiser in DIE FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN, Samson in SAMSON ET DALILA, Don José in CARMEN and Pollione in NORMA. All in all, he has performed close to fifty leading roles. The many works he has performed in concert include Verdi’s REQUIEM, Mahler’s DAS LIED VON DER ERDE and SYMPHONY NO. 8, and Beethoven’s SYMPHONY NO. 9 with orchestras worldwide. Among his recordings are the title role in DON CARLO with James Levine (Sony Classics), Adorno in SIMON BOCCANEGRA with Sir Georg Solti (Decca), Calaf in TURANDOT (EMI video), Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 with Robert Shaw (Telarc) and Mendelssohn’s Die ertse Walpurgisnacht (Arabesque). Additionally, he has been featured in numerous Saturday afternoon radio broadcasts from the Metropolitan Opera, and in other broadcast and televised performances around the world. Mr. Sylvester served on the faculty of DePaul University for seven years, and he has also been on the faculty at Indiana University and the University of Indianapolis. After serving as Master Teacher-in-Residence for the 2014 Concurso San Miguel, he was recently named Master Teacher and Artist-in-Resdence for this opera competition, the largest for Mexican opera singers. In 2013 he was invited to be the Artist-in-Residence at the Art Song Festival at the University of Toledo. Mr. Sylvester has taught annually at the iSing! Festival in Suzhou, China and at Chicago Summer Opera. He has students performing in North America and Europe, and several that have been successful in national competitions. He is Co-Founder and Co-Director of the San Miguel Institute of Bel Canto, which celebrated its third season in the summer of 2017. In recent years, Mr. Sylvester has turned his performing talents toward recital and concert work, having given recitals in Chicago, Rochester (New York), Atlanta, Toledo (Ohio), Indianapolis, San Miguel de Allende (Mexico) and Ridgefield (Connecticut). Concerts have included Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9. He has just finished his first book, English Diction and Enunciation for North American Singers, and is finalizing its publication and eventual e-book publication. Currently he is working on a project called A Survey of Historically Important Classical Singers of the 20th Century, an audio project aimed at introducing young singers to the singers that came before them. == Biography from the Wichita State University

website (with additions and corrections)

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on September 21, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 2001. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.