|

Martti Talvela, 54, Imposing Bass Regarded as

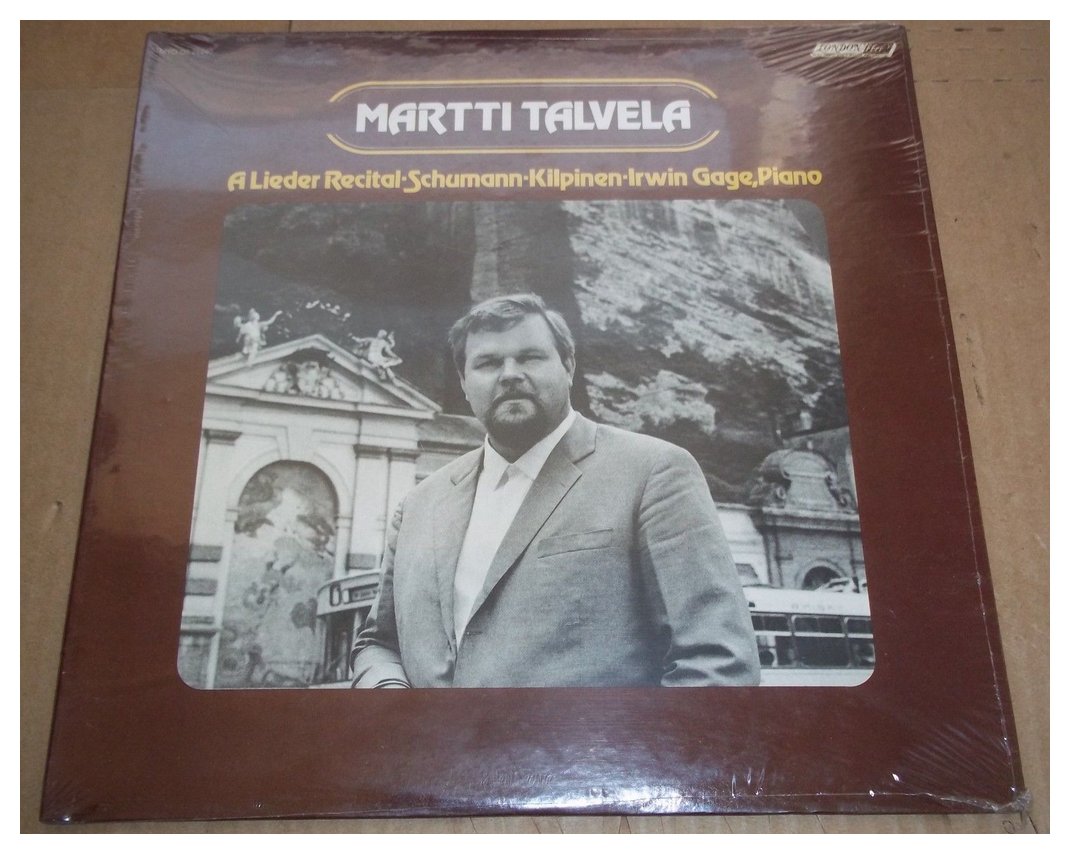

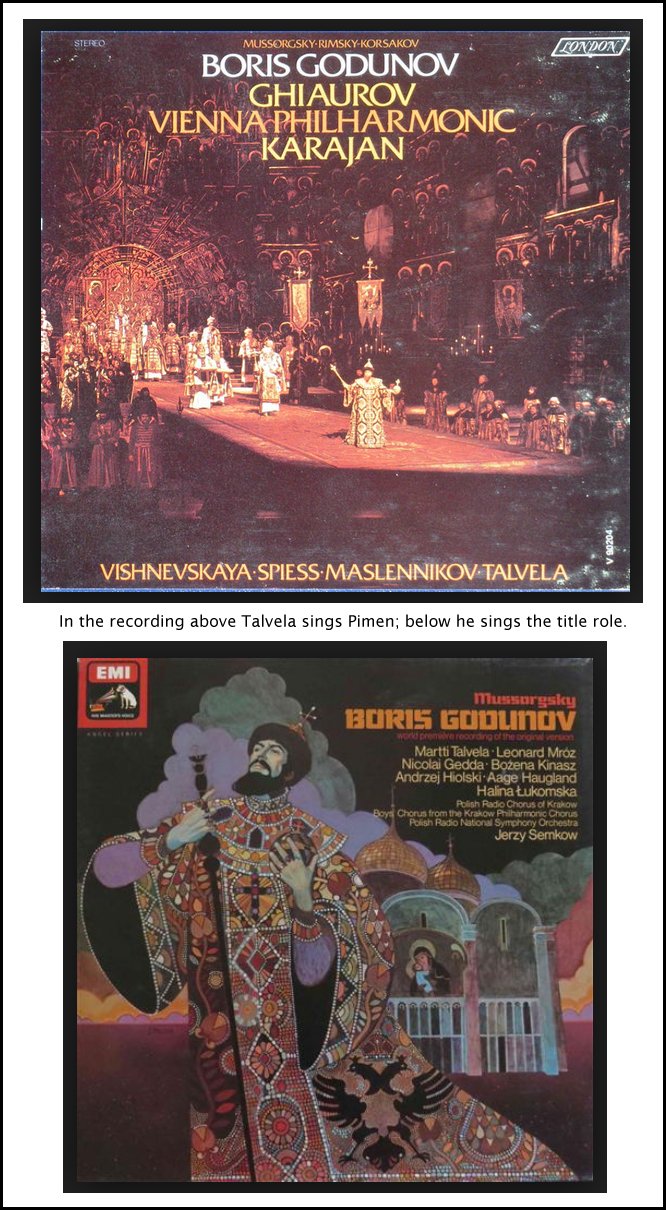

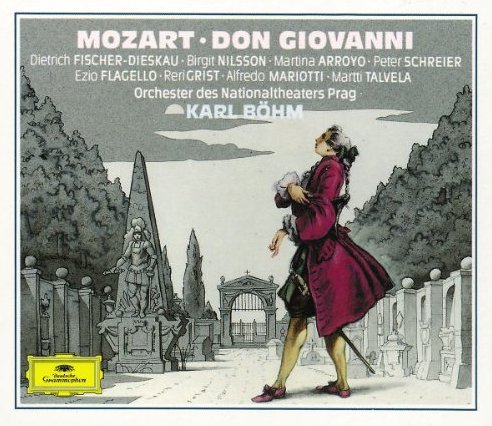

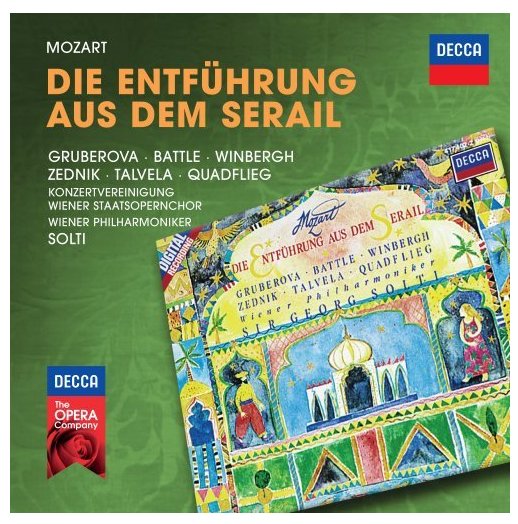

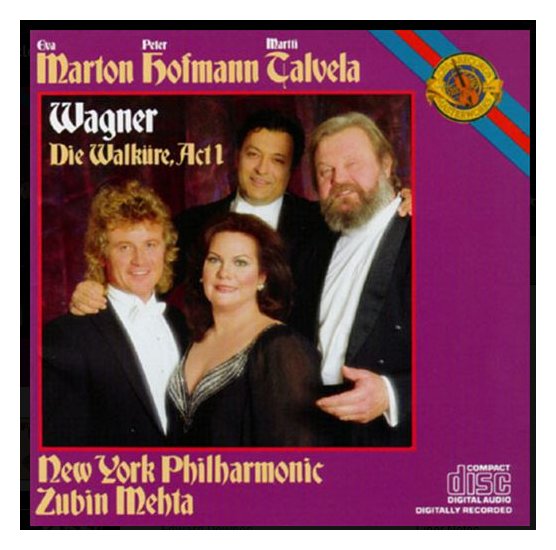

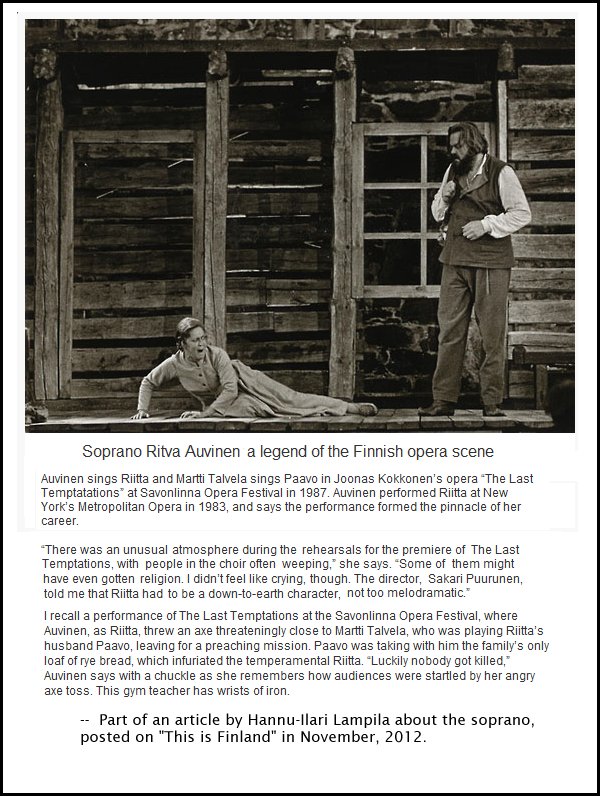

Peerless in 'Godunov'

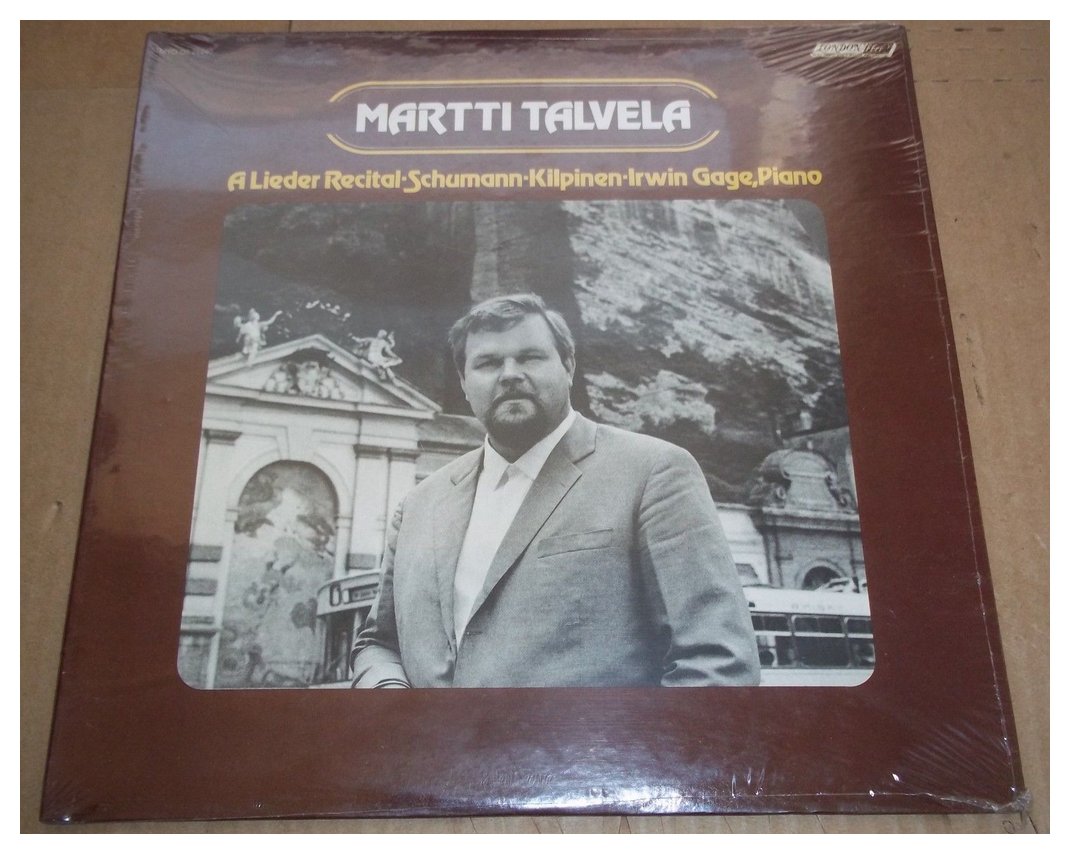

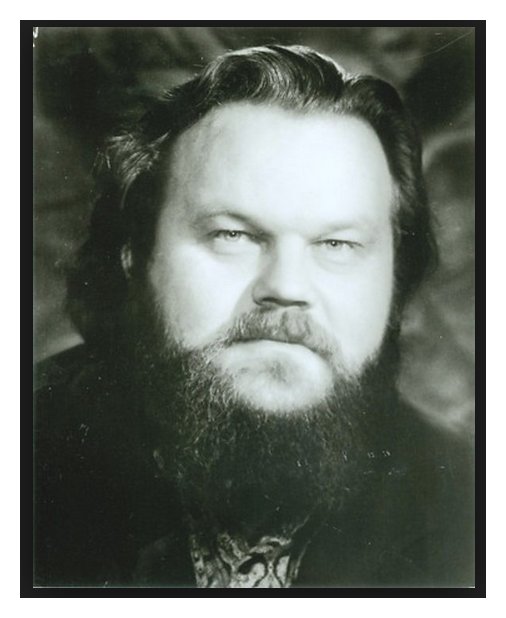

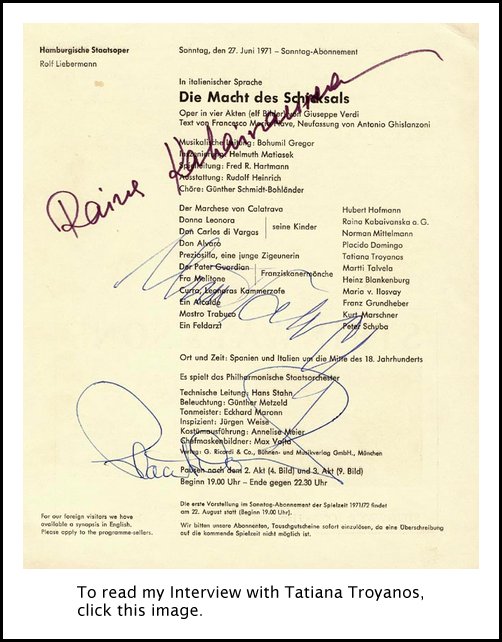

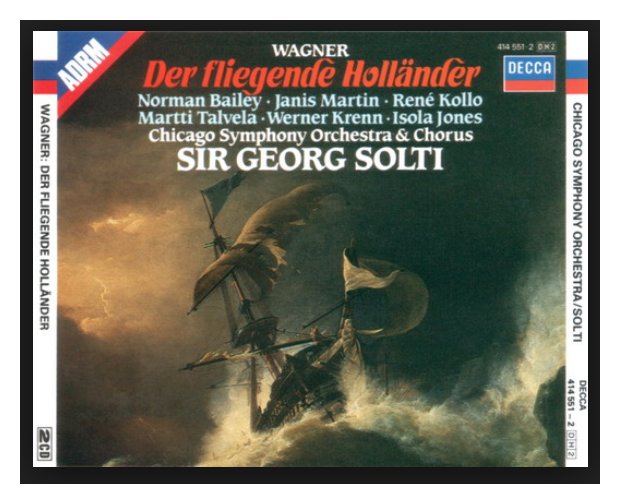

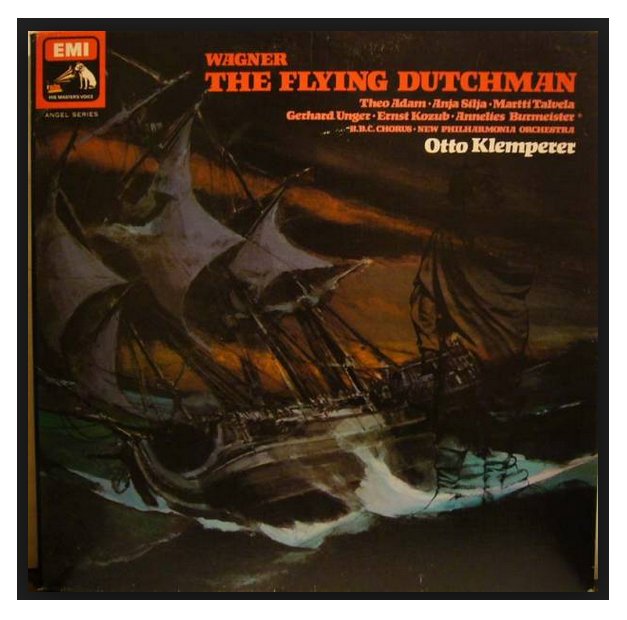

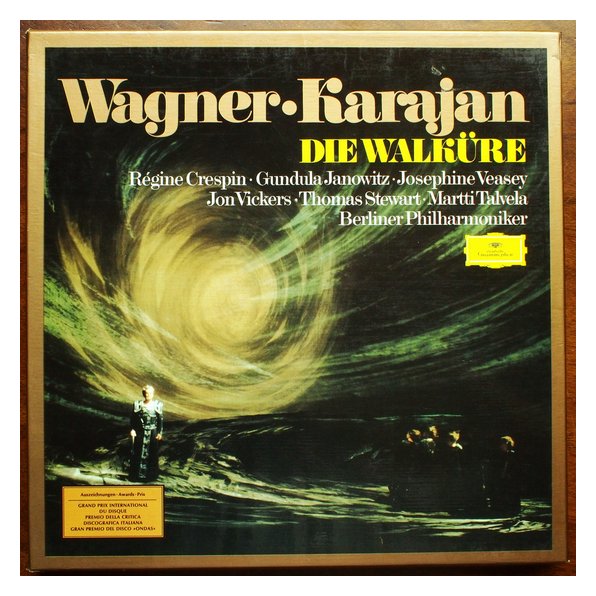

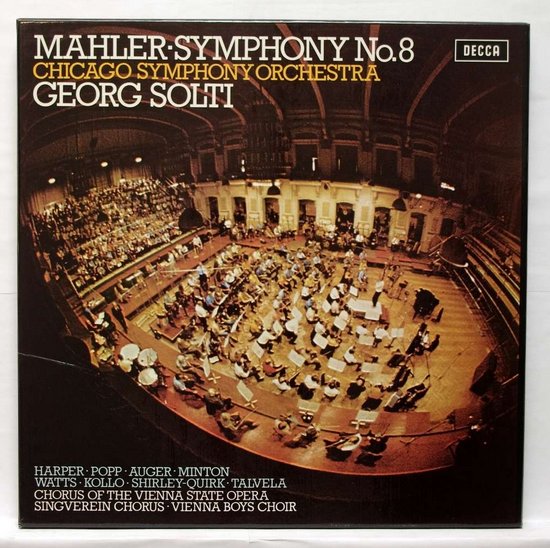

By ALLAN KOZINN Published: July 24, 1989, in The New York Times Martti Talvela, a Finnish bass who appeared regularly at the Metropolitan Opera and was the director-designate of the Finnish National Opera, died on Saturday after suffering a heart attack at his daughter's wedding on his farm in Juva, Finland. He was 54 years old. Mr. Talvela was most highly regarded in the Russian operatic repertory, and was considered a peerless interpreter of the title role in Modest Mussorgsky's ''Boris Godunov,'' which he sang many times at the Metropolitan Opera. He also enjoyed considerable success as Dosifei in the Met's production of Mussorgsky's ''Khovanshchina'' in recent seasons. But his repertory also encompassed the Wagner operas - he was noted for his portrayals of King Marke in ''Tristan und Isolde,'' Gurnemanz in ''Parsifal'' and Daland in ''The Flying Dutchman'' -as well as several Verdi and Mozart roles. His physical stature made him a natural for the mythical roles that were his specialty. He stood 6 feet 7 inches tall, and weighed close to 300 pounds. The singer was born in Hiitola, Finland, on Feb. 4, 1935, the eighth of 10 children in a family of farmers and amateur singers. He earned his first singing fee at the age of 5, and became interested in opera after hearing a performance by the Russian bass Ivan Petrov, as Boris. In 1958, after completing his college studies in Savonlinna, and working for a few years as a schoolmaster, he entered the Lahti Academy of Music to pursue formal voice studies. In January 1960, he won first prize in a lieder competition in Helsinki, and went to Stockholm to continue his studies with Carl Martin Ohmann. The following year he made his debut, as Sparafucile in Verdi's ''Rigoletto,'' at the Swedish National Opera. Wieland Wagner, the composer's grandson and a noted stage director, heard one of Mr. Talvela's early performances and invited him to appear at Bayreuth in 1962. In 1963, he made his debut with the Deutsche Oper, in Berlin, and toured Japan with that company as Seneca in Monteverdi's ''Incoronazione di Poppea.'' By 1965, he had made debuts at La Scala, in Milan, and at the Vienna State Opera, and was performing regularly at Bayreuth and Salzburg. Mr. Talvela made his American debut with a recital at Hunter College in 1968, and with performances at the Metropolitan Opera that same year. From 1972 to 1980, he was the director of the Savonlinna Festival, where he worked steadfastly to promote the cause of opera in Finland, both by performing standard repertory works in Finnish, and by encouraging Finnish composers to write for him and for the festival. He was to become the director of the Finnish National Opera in 1992. |

Being a work without intermission, the entire cast of singers came onstage

at the very beginning. It was an impressive line of artists, but what

struck me then — and remains with me

to this day — was watching the procession come through the

door. From the back and to the side of the stage, each walked nobly

through the violins to their seats at the front. To get beyond the stage

door, they had to pass under a small structural overhang where the chorus

was seated behind the orchestra. Soloists and conductors came from

this space all the time for their performances, and as these particular singers

entered, they were in an appropriate order to be with the others with whom

they would interact in Wagner’s music drama. In the midst

of the group were the two giants, Fafner and Fasolt, played by Hans Sotin and Martti Talvela.

Sotin was a large man himself, and as he walked through and Talvela followed,

each appeared to be about the same height. It wasn’t until

a few paces after they had cleared the overhang that Talvela stood fully

erect and quite literally towered over the other giant — as

well as everyone else! The audience was applauding the entire cast,

but I did notice an audible gasp as Talvela straightened himself.

Being a work without intermission, the entire cast of singers came onstage

at the very beginning. It was an impressive line of artists, but what

struck me then — and remains with me

to this day — was watching the procession come through the

door. From the back and to the side of the stage, each walked nobly

through the violins to their seats at the front. To get beyond the stage

door, they had to pass under a small structural overhang where the chorus

was seated behind the orchestra. Soloists and conductors came from

this space all the time for their performances, and as these particular singers

entered, they were in an appropriate order to be with the others with whom

they would interact in Wagner’s music drama. In the midst

of the group were the two giants, Fafner and Fasolt, played by Hans Sotin and Martti Talvela.

Sotin was a large man himself, and as he walked through and Talvela followed,

each appeared to be about the same height. It wasn’t until

a few paces after they had cleared the overhang that Talvela stood fully

erect and quite literally towered over the other giant — as

well as everyone else! The audience was applauding the entire cast,

but I did notice an audible gasp as Talvela straightened himself.  MT: For Gurnemanz, especially in the third

act, and for King Marke, the writing is so difficult. That makes it

interesting. Daland is so easy and the line is so easy to sing.

Parsifal is so, so long. The

part’s about one hour forty minutes of singing, but it is written easy.

The most difficult role is King Marke, to make the pitch clean and everything.

But it is so interesting to make the difference. For instance, with

Gurnemanz, in the first act, Wagner says he is a valiant but older man.

He’s a man about fifty, and then for the third act Wagner says many years

have passed.

MT: For Gurnemanz, especially in the third

act, and for King Marke, the writing is so difficult. That makes it

interesting. Daland is so easy and the line is so easy to sing.

Parsifal is so, so long. The

part’s about one hour forty minutes of singing, but it is written easy.

The most difficult role is King Marke, to make the pitch clean and everything.

But it is so interesting to make the difference. For instance, with

Gurnemanz, in the first act, Wagner says he is a valiant but older man.

He’s a man about fifty, and then for the third act Wagner says many years

have passed. BD: Do you sing any of your roles anymore in translation?

BD: Do you sing any of your roles anymore in translation?

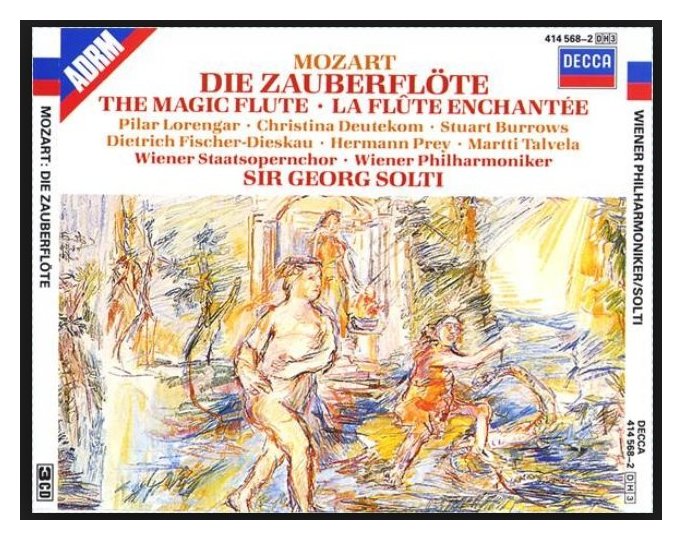

To read my Interview with C(h)ristina Deutekom, click HERE. To read my Interview with Hermann Prey, click HERE.

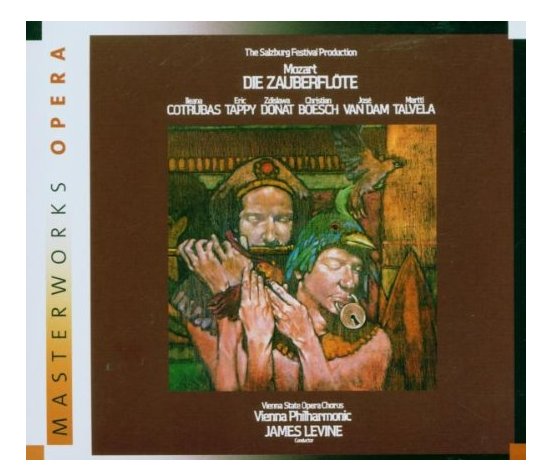

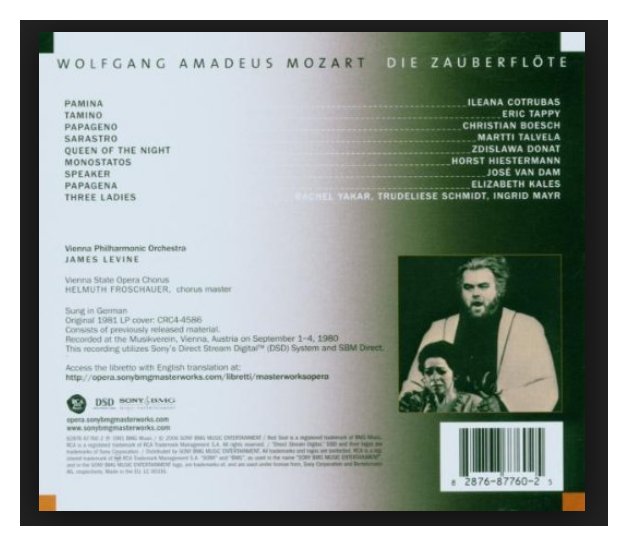

To read my Interview with Ileana Cotrubas, click HERE. To read my Interview with Jose Van Dam, click HERE. To read my Interivew with James Levine, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Martina Arroyo, click HERE. To read my Interview with Peter Schreier, click HERE.

To read my Interviews with Gösta Winbergh, click HERE. |

MT: Yes, I try to do that, but always we have some

important things coming up so I can’t say no. I feel it’s so important...

For instance, I’m going next summer, in July when I do usually not sing anything,

to Israel for Babi Yar six times

with Zubin Mehta.

This is a fantastic work, as you know, and it’s very difficult. I

learned it for Montreal about six years ago, but I was ill at that time and

had to cancel a couple of months of my traveling. Now finally I can

do it.

MT: Yes, I try to do that, but always we have some

important things coming up so I can’t say no. I feel it’s so important...

For instance, I’m going next summer, in July when I do usually not sing anything,

to Israel for Babi Yar six times

with Zubin Mehta.

This is a fantastic work, as you know, and it’s very difficult. I

learned it for Montreal about six years ago, but I was ill at that time and

had to cancel a couple of months of my traveling. Now finally I can

do it. BD: So the flute not only mesmerizes the animals

but also the woods?

BD: So the flute not only mesmerizes the animals

but also the woods? MT: I was thinking in the very beginning of

my direction in Savonlinna, we have to change to something, to bring in more

people from the acting side, from the theaters. I was lucky enough to

get three people who had the musicality to listen to the music for all those

Finnish operas I did, and, of course, for Boris Godunov. All those stage directors

came from the theater. Internationally, however, I wouldn’t see the

situation as being so happy. You see, the music is the main thing in

other operas. Music has to have the possibility to speak or to sing

out those emotions and situations, and they have a stage director who doesn’t

know anything about music. I feel they even maybe hate or see the music

as disturbing, because the timing for the staging is already there in the

music. If you don’t know the music and the timing in the music, you

cannot listen to what is specifically possible. But this happens sometimes,

and maybe too often today in the world. If you can find a situation

when the stage director has an understanding for music and for theater, then

we could be very happy. But it’s not very often...

MT: I was thinking in the very beginning of

my direction in Savonlinna, we have to change to something, to bring in more

people from the acting side, from the theaters. I was lucky enough to

get three people who had the musicality to listen to the music for all those

Finnish operas I did, and, of course, for Boris Godunov. All those stage directors

came from the theater. Internationally, however, I wouldn’t see the

situation as being so happy. You see, the music is the main thing in

other operas. Music has to have the possibility to speak or to sing

out those emotions and situations, and they have a stage director who doesn’t

know anything about music. I feel they even maybe hate or see the music

as disturbing, because the timing for the staging is already there in the

music. If you don’t know the music and the timing in the music, you

cannot listen to what is specifically possible. But this happens sometimes,

and maybe too often today in the world. If you can find a situation

when the stage director has an understanding for music and for theater, then

we could be very happy. But it’s not very often...

To read my Interview with Norman Bailey, click HERE. To read my Interview with Janis Martin, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Anja Silja, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Régine Crespin, click HERE. To read my Interview with Jon Vickers, click HERE. To read my Interviews with Thomas Stewart, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Joan Sutherland, click HERE. To read my Interview with Marilyn Horne, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Arleen Augér, click HERE. To read my Interviews with Yvonne Minton, click HERE. To read my Interview with John Shirley-Quirk, click HERE. |

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on April 13, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990, and again in 1995 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.