|

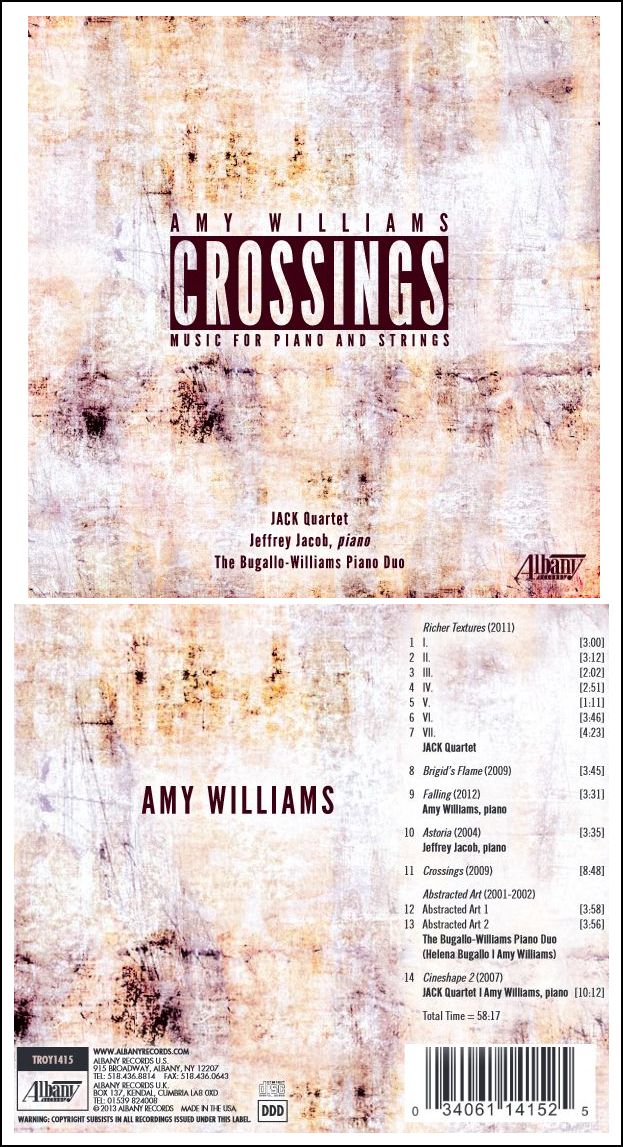

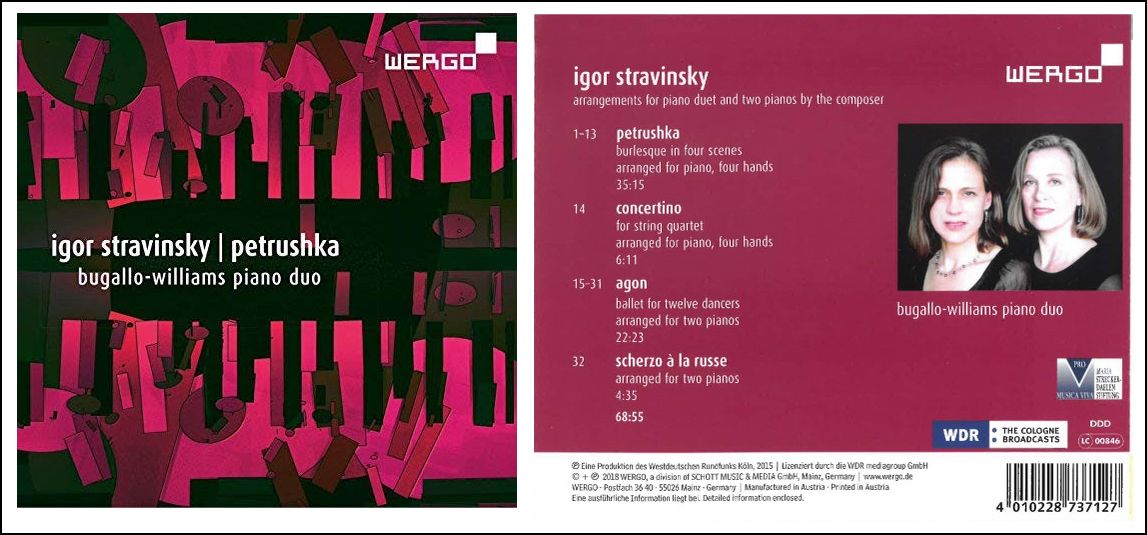

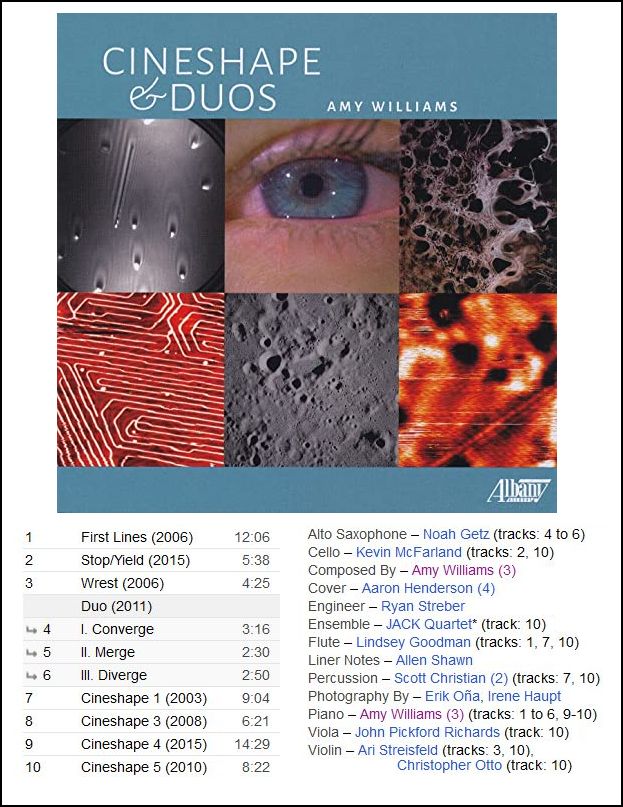

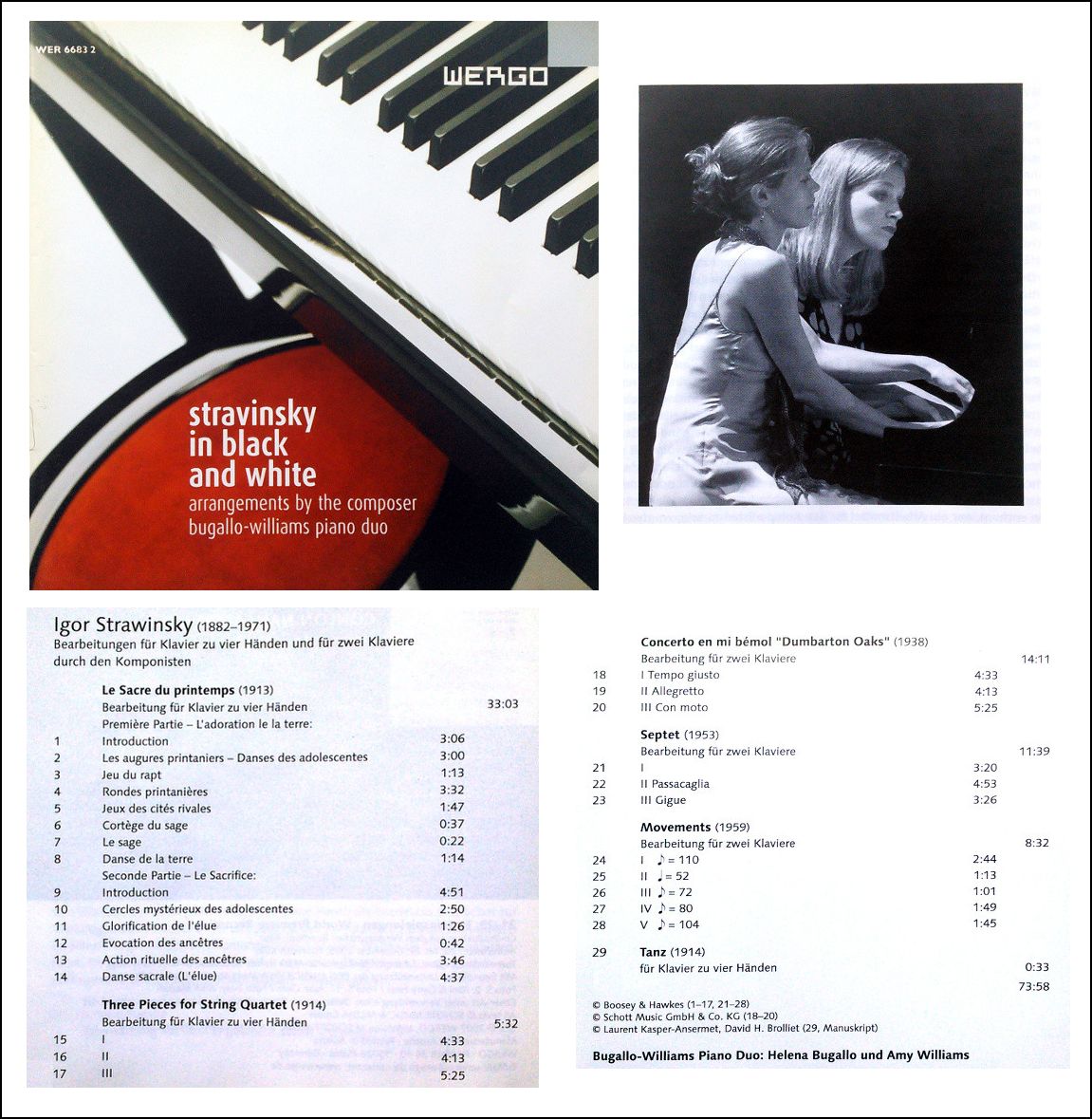

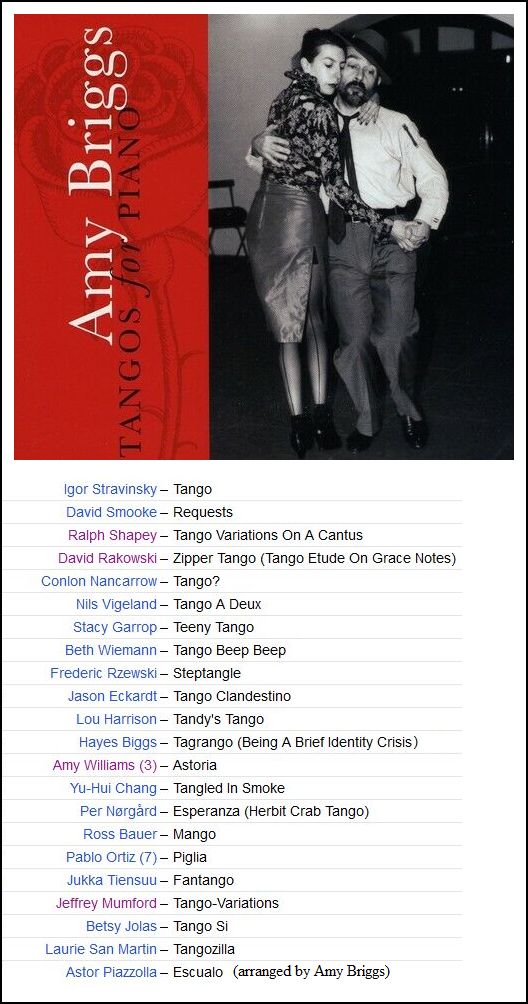

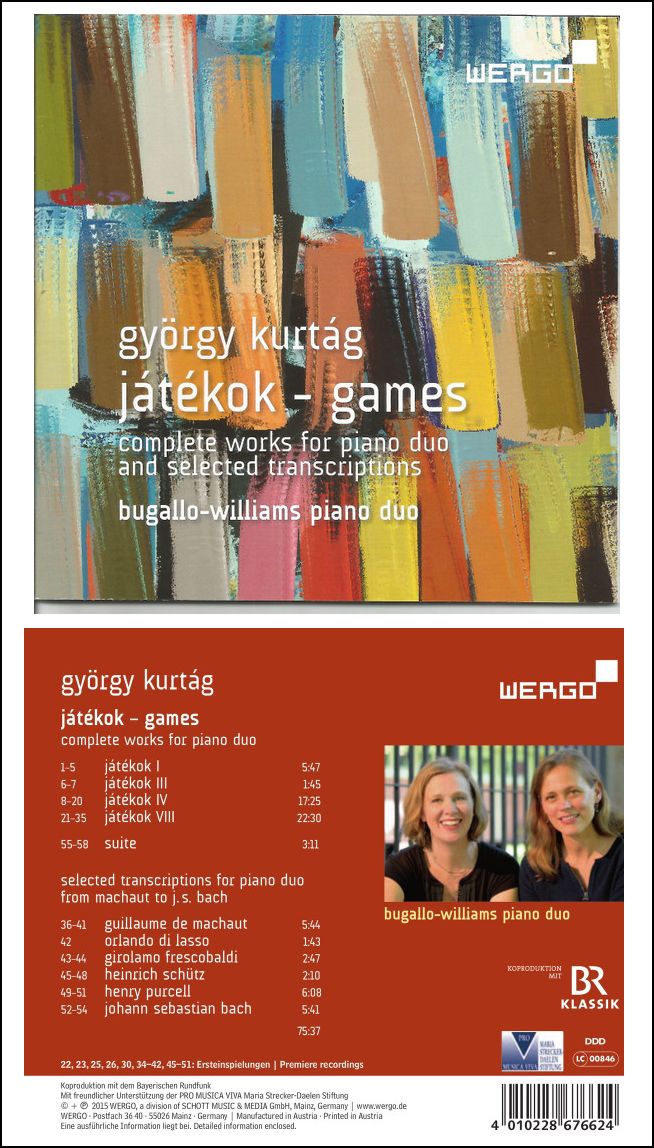

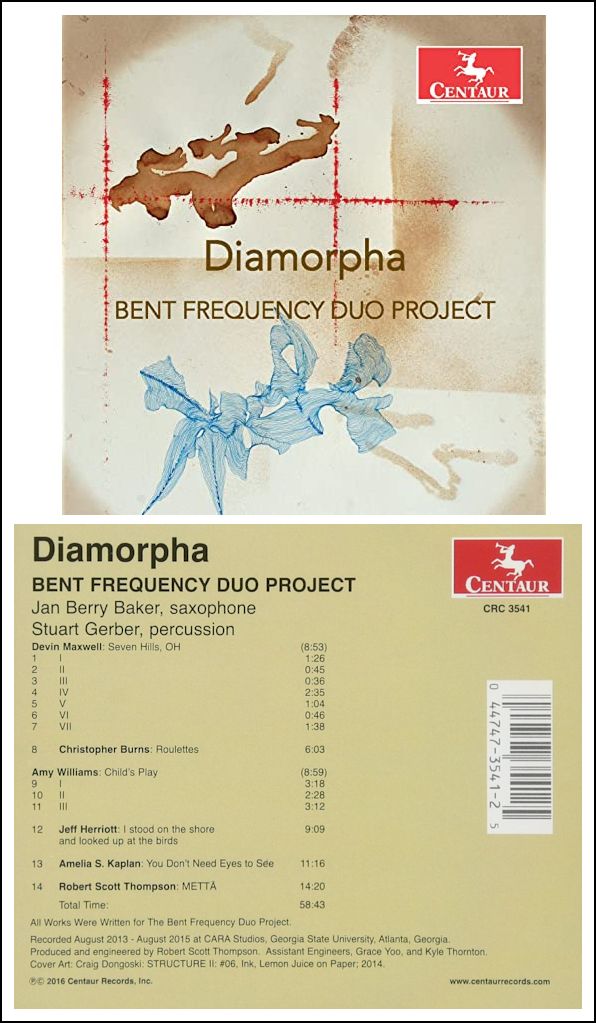

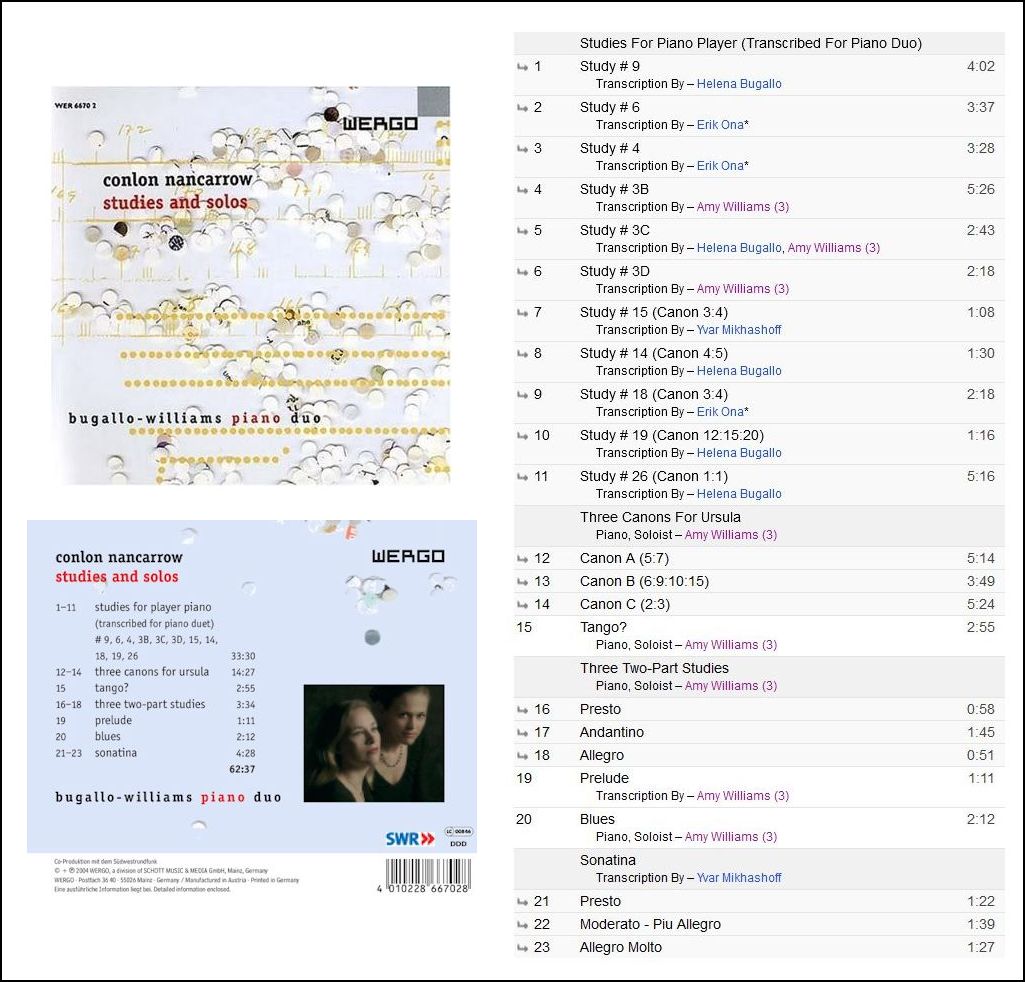

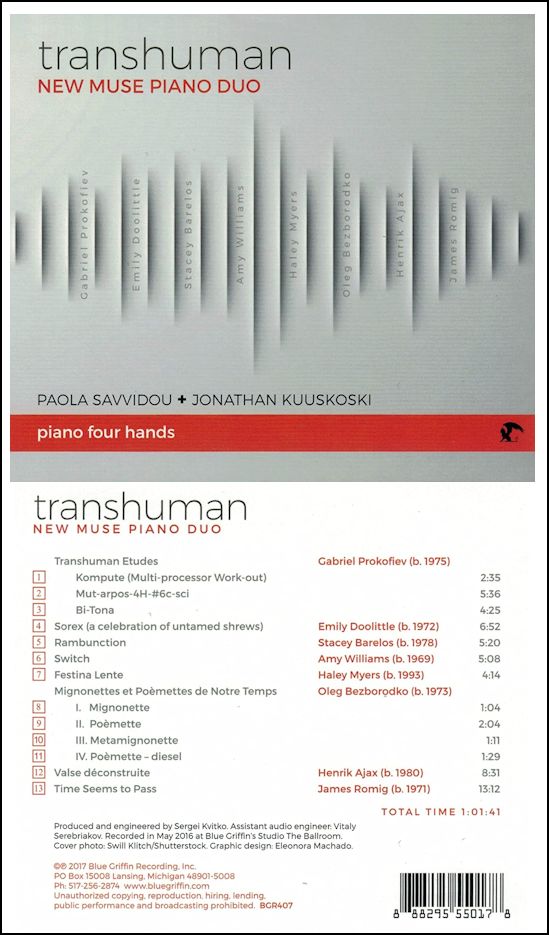

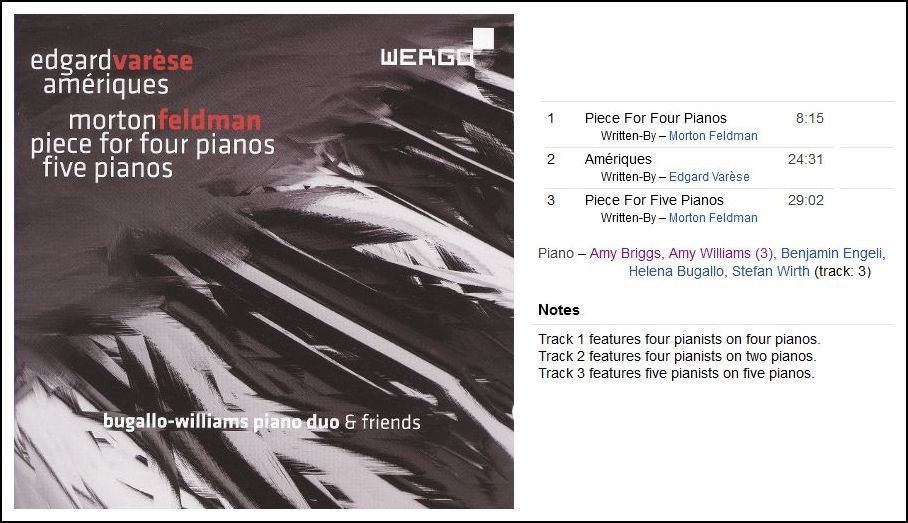

Amy Williams was born in Buffalo, NY in 1969, the daughter of Diane, now retired violist with the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, and Jan, percussionist and Professor Emeritus at the University at Buffalo. She started playing the piano at the age of four and took up the flute a few years later (her first teacher was the legendary Robert Dick, so she could soon play “Chopsticks” in multiphonics…). She grew up in the heyday of the Center for the Creative and Performing Arts, hearing all the latest contemporary music and meeting composers who would later become influential to her: John Cage, Morton Feldman, Lukas Foss, Elliott Carter, Julius Eastman and many others. She went to Bennington College and, while there, decided to devote her life to performing and composing contemporary music. After a fellowship year in Denmark, she returned to Buffalo to complete her Master’s degree in piano performance at the University at Buffalo with pianist-composer Yvar Mikhashoff and her Ph.D. in composition, working with David Felder, Charles Wuorinen and Nils Vigeland. She returned to Bennington in 1998 as a member of the music faculty and she then moved on to a faculty position at Northwestern University in 2000. Since 2005, she has been teaching composition and theory at the University of Pittsburgh, where she is an Associate Professor. She was a 2017-2018 Fulbright Scholar at the University College Cork, Ireland and a Visiting Professor of Composition at the University of Pennsylvania in spring 2019. Amy’s compositions have been presented at renowned contemporary music venues in the United States, Asia, Australia, and Europe, including Ars Musica (Belgium), Gaudeamus Music Week (Netherlands), Dresden New Music Days (Germany), Festival Aspekte (Austria), Festival Musica Nova (Brazil), Lucerne Festival (Switzerland), Thailand International Composition Festival, Music Gallery (Canada), LA County Museum of Art, Piano Spheres (Los Angeles), Lincoln Center, Roulette, Bargemusic (NYC) and Tanglewood Festival of Contemporary Music. Her works have been performed by leading soloists and ensembles, including the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, JACK Quartet, Ensemble Musikfabrik, Ensemble Surplus, Dal Niente, Wet Ink, Talujon, International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), H2 Saxophone Quartet, Bent Frequency, Grossman Ensemble, pianist Ursula Oppens and bassist Robert Black. Amy’s pieces appear on the Parma, VDM (Italy), Centaur, Blue Griffin, New Focus and New Ariel labels, in addition to two portrait CDs of solo and chamber works on Albany Records: “Crossings: Music for Piano and Strings” (2013) and “Cineshape and Duos” (2017). Amy formed the Bugallo-Williams Piano Duo with Helena Bugallo, while both were graduate students at the University at Buffalo. The Duo has been featured at important contemporary music festivals and series throughout Europe and the Americas, including the Ojai Festival, CAL Performances (California), Miller Theatre (New York), Ciclo de Música Contemporánea (Buenos Aires), Festival Attacca (Stuttgart), Palacio de Bellas Artes (Mexico City), Warsaw Autumn Festival, Cologne Triennale, and Wittener Täge für Neue Kammermusik. The Duo’s debut CD of Conlon Nancarrow’s complete music for solo piano and piano duet (Wergo, 2004) garnered much critical acclaim. Subsequent Duo CDs on Wergo include, Stravinsky transcriptions (2007), Morton Feldman/Edgard Varèse (2009), György Kurtág (2015) and a second volume of Stravinsky transcriptions (2018), as well as the original version of Bartók’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion in a recently published facsimile. Amy has performed John Cage’s masterpiece, The Sonatas and Interludes, all over the country and often includes new interludes written for her by over a dozen composers. Amy has received fellowships from the American Academy

of Arts and Letters (Goddard Lieberson Fellowship), American-Scandinavian

Foundation, Howard Foundation and John S. Guggenheim Foundation. She

received a Fromm Music

Foundation Commission to write “Richter Textures” for the JACK Quartet

and a Koussevitsky Foundation commission for soprano Tony Arnold and the

JACK Quartet. An avid proponent of contemporary music, she served as Assistant

Director of June In Buffalo, Director of New Music Northwestern, and is

currently on the artistic boards of the Pittsburgh-based concert series,

Music on the Edge, the Amphion Foundation and the Yvar Mikhashoff Trust

for New Music. She has been the Artistic Director of the New Music On The

Point festival in Vermont since 2015. == Biography from the composer's website

== Throughout this webpage, links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Under Maazel's direction, the Pittsburgh Symphony commissioned several works to showcase principal players: Benjamin Lees' Horn Concerto, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich's Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra, Leonardo Balada's Music for Oboe and Orchestra, Rodion Shchedrin's Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra, Roberto Sierra's Evocaciones and Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, and David Stock's Violin Concerto. In January 2004, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra with conductor Gilbert Levine became the first American orchestra to perform at the Vatican for Pope John Paul II to commemorate the Pontiff's Silver Jubilee celebration. The program included the world premiere of Abraham, a sacred motet by John Harbison. Among other premieres, Joan Tower has had two works commissioned: Tambor and Stroke. In 2012, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra commissioned Silent Spring by Steven Stucky in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the publication of Silent Spring, the 1962 seminal work by Pittsburgh-area native Rachel Carson, and in 2018, the orchestra introduced Jennifer Higdon's Tuba Concerto. |

||||

© 2005 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in her office at Northwestern University on June 29, 2005. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.