| Giulio Chazalettes was taught in music by his mother,

a German pianist. After having settled in Milan, he was accepted by the

Piccolo Teatro's acting school. Soon he also joined the company, and appeared

in Sacrilegio massimo by Stefano Landi, and replaced Giorgio

De Lullo in The Madwoman of Chaillot. Later he went to Dresden to

work as an actor and assistant director. Returning to Italy, he finished

his musical education at the Florence Conservatory. Chazalettes then started

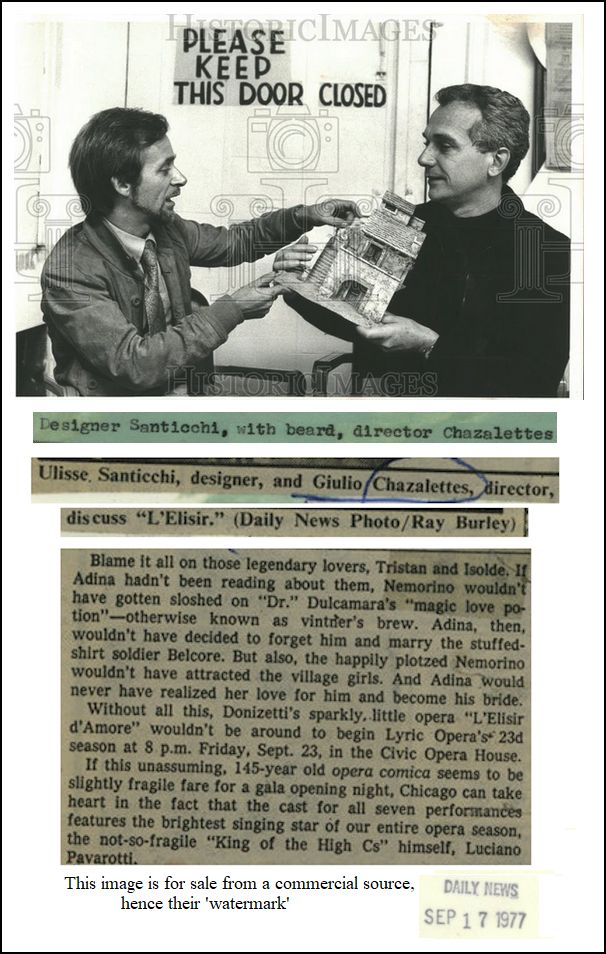

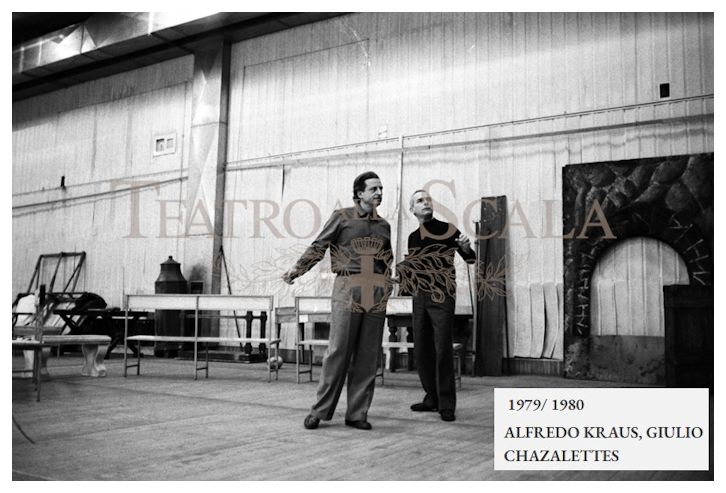

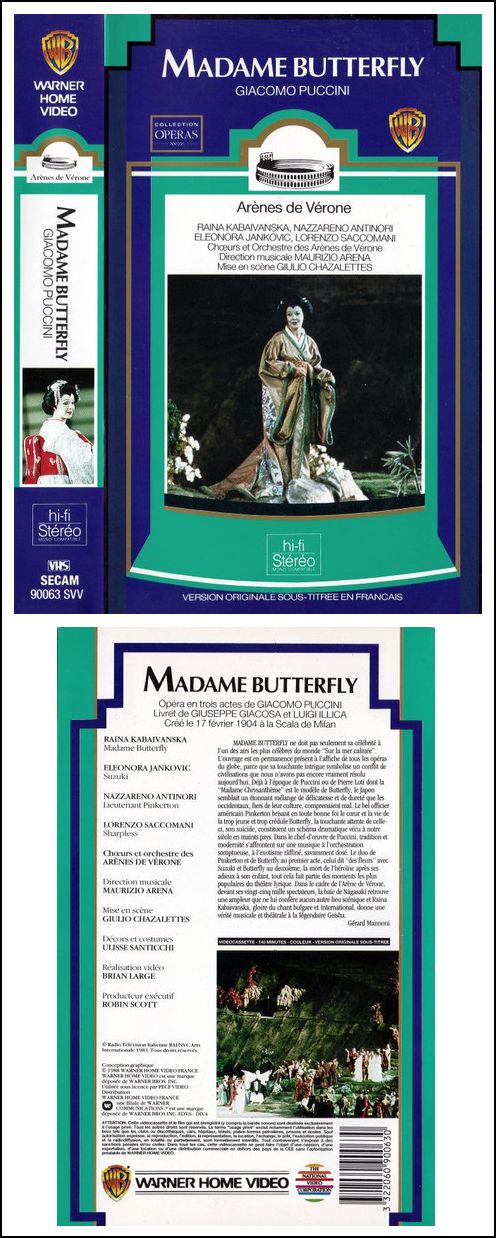

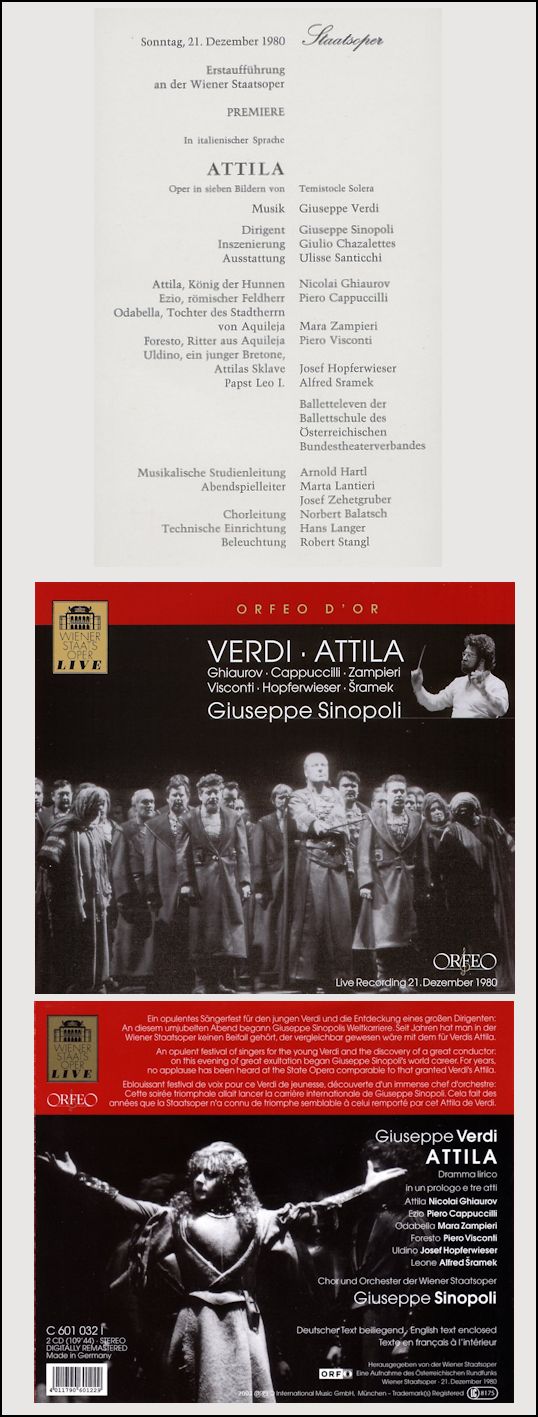

his career as an opera director. In 1976, he debuted at La Scala with Massenet's Werther (featuring Alfredo Kraus, and conducted by Georges Prêtre). [Photo from 1979 revival shown below.] His debut at the Vienna State Opera came in 1980 with Verdi's Attila (conducted by Giuseppe Sinopoli). [Program (and photo of audio recording) shown below.] Chazalettes also worked for the Chicago Lyric Opera and the Bavarian State Opera. In 1989, he directed Frederica von Stade in Massenet's Cherubin for the Santa Fe Opera. == Throughout this webpage, names which are

links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Giulio Chazalettes at Lyric Opera of Chicago

[Chazalettes was the original director in all productions. All except Traviata were designed by Ulisse Santicchi. Photo of the two of them is shown below-right.] 1976 Love for Three Oranges with Barlow, Little, Dooley, Titus, Gill, Tajo, Kuhlmann, Trussel, Powers; Bartoletti 1977 L'elisir d'amore with Rinaldi, Pavarotti, Romero, Evans, Brown; Bartoletti [Photo shown below-right] [Revived 1982, directed by Liotta, with Buchanan, Bergonzi/Pavarotti, Sereni/Duesing, Montarsolo, Harman-Gulick; Bartoletti] 1979 Love for Three Oranges with Souliotis, Little, Dooley, Nolen, Gill, Tajo, White, Trussel, Halfvarson; Prêtre 1985-86 I capuleti e i Montecchi with Gasdia, Troyanos, O'Neill, Kavrakos; Renzetti La rondine with Cotrubas, McCauley, Kunde, Stone, Doss, Langton, Redmon; Bartoletti 1988-89 La Traviata [production designed by Pier Luigi Pizzi] with Tomowa-Sintow, Rosenshein/Hadley, Pons/Ellis; Bartoletti/Fiore 1989-90 Fledermaus with Daniels, Bonney, Rosenshein, Allen/Otey, Nolen, Howells, Adams; Rudel 1991-92 L'elisir d'amore with Gasdia, Hadley, Corbelli (Belcore), Desderi, Futral (Giannetta); Pappano [Revived 1999-2000, directed by Liotta, with Futral (Adina)/Swenson, Lopardo/LaScola, Lanza, Plishka; Abel] [Revived 2009-10, directed by Liotta, with Cabell/Phillips, Filanoti/Lopardo, Viviani, Corbelli (Dulcamara); Campanella 2001-02 I capuleti e i Montecchi with Rost, Kasarova, Sartori, Chiummo; Campanella |

This conversation was recorded in a dressing room backstage at the Civic Opera House in Chicago on December 4, 1985. Portions were broadcast on WNIB a few days later to promote the performances. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to Marina Vecci, Artistic Administrator of Lyric Opera for translating during the interview. Also, my thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.