|

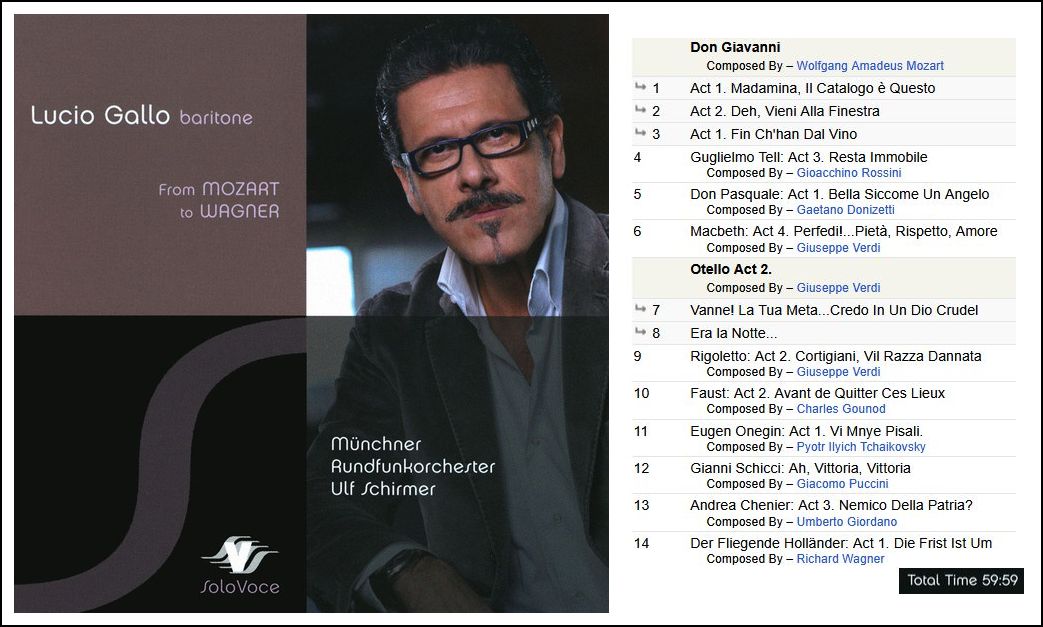

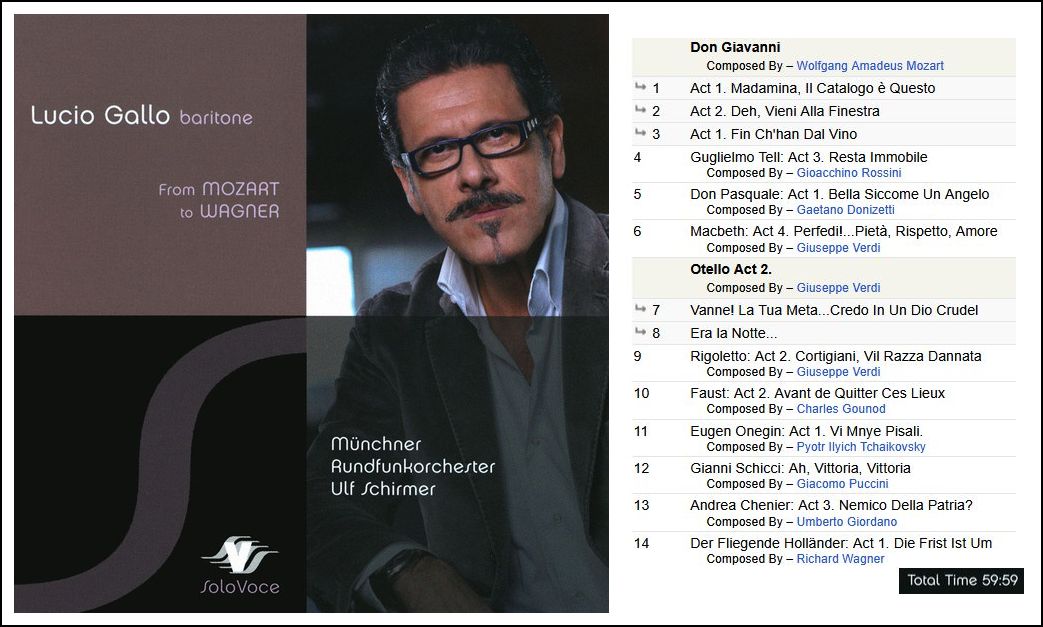

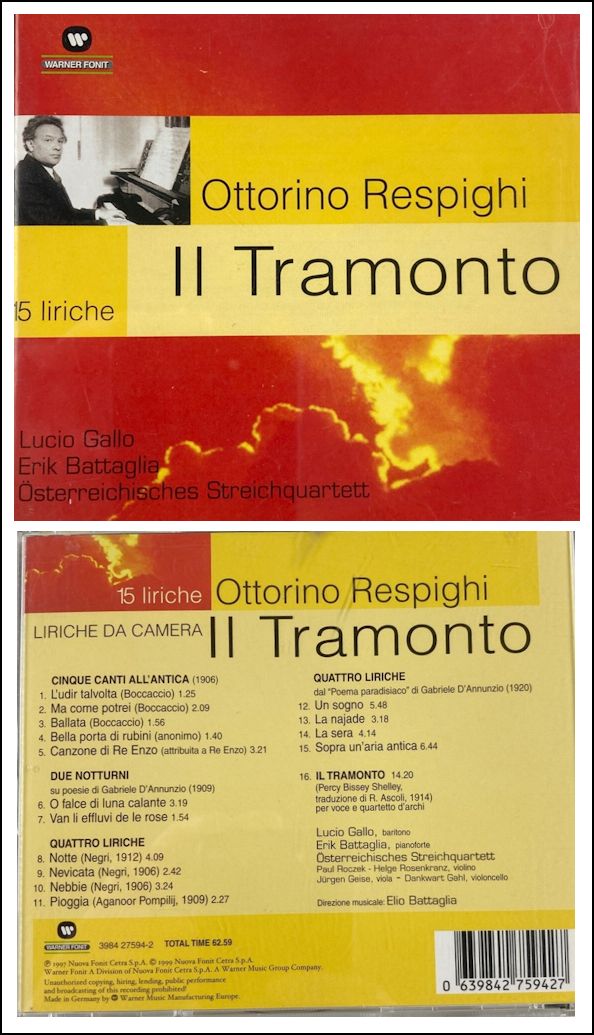

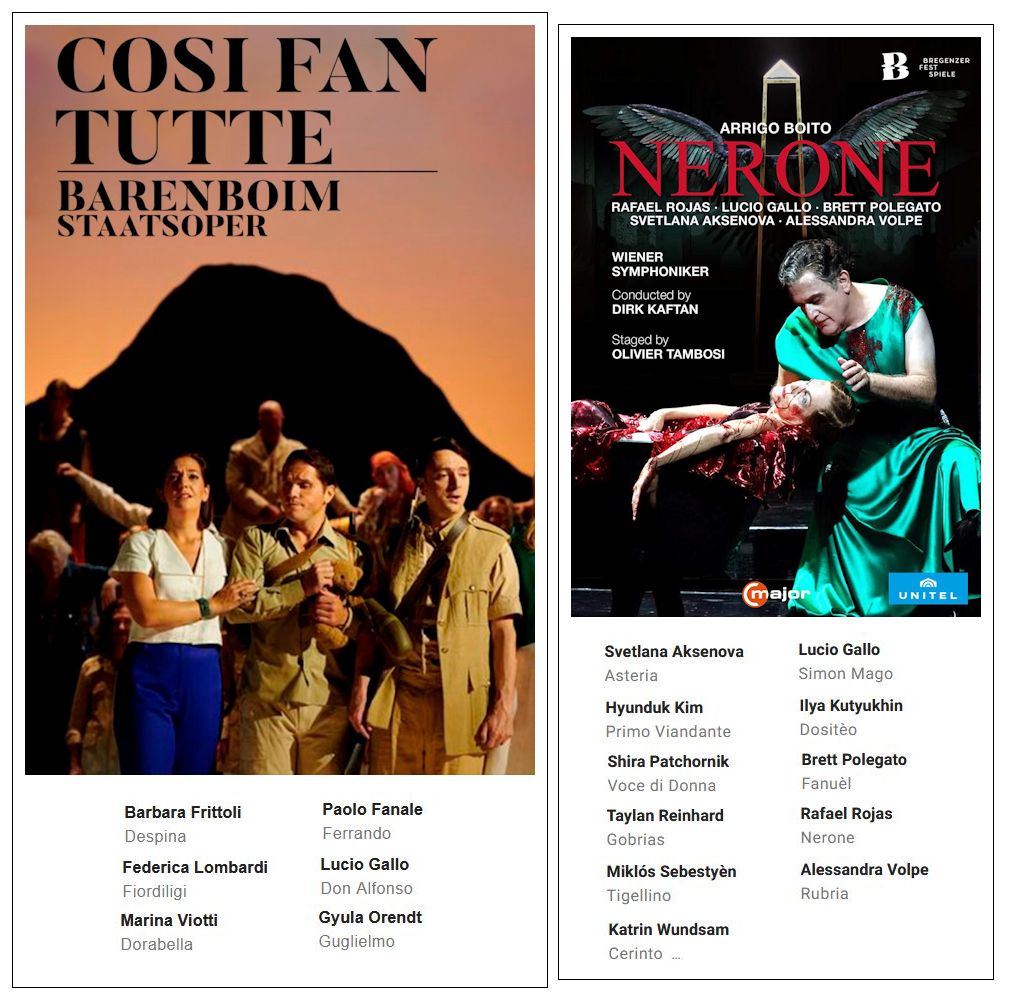

Lucio Gallo (born July 9, 1959) was a student of Elio Battaglia. Gallo graduated from the Turin Conservatory and made his stage debut in 1984. He has performed in important theaters and concert halls, such as the Teatro alla Scala, the Metropolitan Opera in New York, the San Francisco Opera, the Lyric of Chicago, the Covent Garden in London, the Liceu in Barcelona, the Staatsoper in Vienna, the Opera Bastille in Paris, the Staatsoper Unter Den Linden and the Deutsche Oper in Berlin, the Teatro Real in Madrid, the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, the Salzburg Festival, the Bregenz Festival, the Teatro Regio in Turin, the Regio in Parma, the Comunale in Bologna, the Teatro Massimo in Palermo, the Arena in Verona, the Fenice in Venice, the Zurich Opera, the Musikverein in Vienna, the Royal Albert Hall in London and the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. He has participated in productions conducted by conductors such as Claudio Abbado, Daniel Barenboim, Riccardo Chailly, Colin Davis, Gianandrea Gavazzeni, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Bernard Haitink, Riccardo Muti, Antonio Pappano, Zubin Mehta, Wolfgang Sawallisch, and Jeffrey Tate. His repertoire includes roles mainly

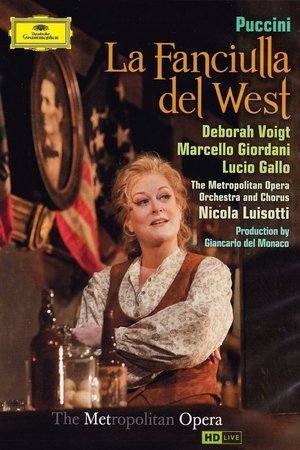

by Rossini, Mozart, Verdi, Puccini and Wagner. Among the most performed operas

are The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, The Barber of Seville, Journey to Reims, Don Carlo, Otello, Falstaff, Simon Boccanegra, Tosca, Il tabarro, Gianni Schicchi, La fanciulla del West, Andrea Chenier, and Parsifal. == Biography is a slightly

edited version of the Google translation from the Italian Wikipedia |

|

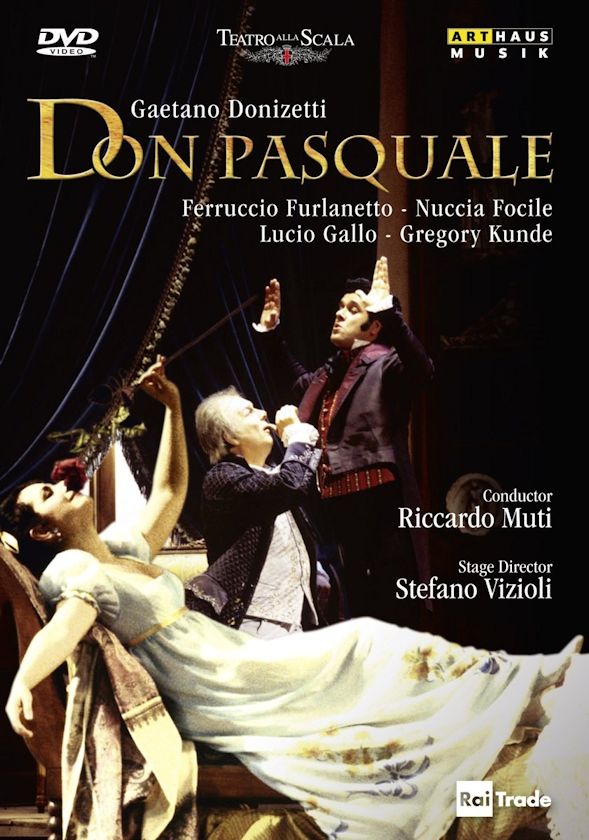

Battaglia was born in Palermo, Italy, and was educated at the schools of Adami Corradetti and Erik Werba, before earning a diploma in singing from the Benedetto Marcello conservatoire in Venice. He then went on to study for a Doctorate in Lieder and Oratorio from University of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna. Battaglia is most renowned as a singing teacher of opera, oratorio and art song, and was the first Italian teacher to specialize in German Lieder. In 2004, he gave master classes at the Music Academy of the West in Montecito, California, hosted by Marilyn Horne. Across Europe, his master classes have been hosted by institutions including the Accademia Musicale Pescarese since 1984, and the Mozarteum since 1993. Between 1967 and 1997, he taught singing at the Conservatorio Statale di Musica Giuseppe Verdi in Turin. [In the photo at right, the portrait behind Gallo is Brahms.] He gave advanced master classes and courses in universities and conservatoires internationally, including in the United States, the former USSR, China, Japan, Korea and Europe. In Italy he organized and held advanced vocal courses and seminars in Turin, (Teatro Regio, Conservatorio G. Verdi), Sienna (Accademia Chigiana), Parma (Festival Verdi), Rome (Università La Sapienza), Tolentino (Teatro Vaccaj), Napoli (Conservatorio S. Pietro a Majella), Catania (Istituto Bellini), and Milan (Conservatorio G. Verdi). He was often invited to sit on judging panels in international competitions such as the Hugo Wolf International Lied Competition in Vienna, Austria and Stuttgart, Germany, and was, in 2005, the jury chairman for the 2005 Renata Tebaldi Competition in San Marino. As an author, he wrote many essays and articles regarding vocal art, and edited the new teachers' edition of The Practical Method of Italian Singing by Nicola Vaccai. He also edited an Anthology of the German Lieder. Battaglia was often considered to be a world leader in singing teaching, and an expert regarding the works of Hugo Wolf. Italian music critic and author Massimo Mila (who writes for La Stampa and l'Unità) wrote of Maestro Battaglia: "...thanks to his passionate teaching style and large numbers of resident students, he has almost turned the Turin Conservatory into a branch office of the Vienna University of Music and Dramatic Art." Battaglia's teaching was so influential that for the 1991–1992 opera

season's opening night at Teatro Regio in Turin, conductor Maurizio Benini

cast Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel entirely from Battaglia's

studio of singers. No event

like this had ever happened before in Italy. In 1987, he was awarded the Hugo Wolf Medal from the International

Hugo Wolf Society of Vienna for his artistic achievements. [Note that Erik Battaglia, Elio's son, is the pianist on several of Gallo's recordings.] |

© 199 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 21, 1999. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 2001. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.