A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

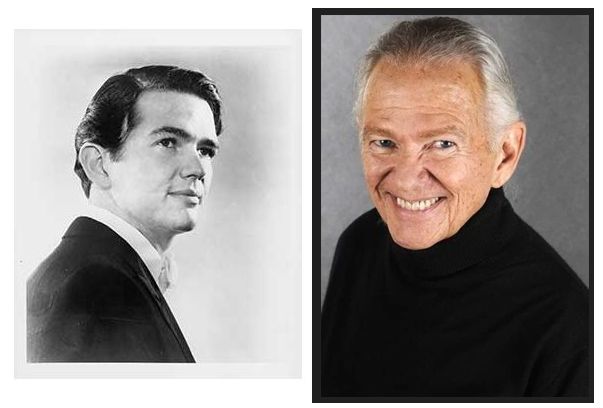

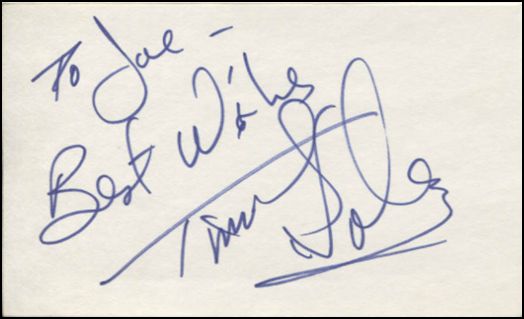

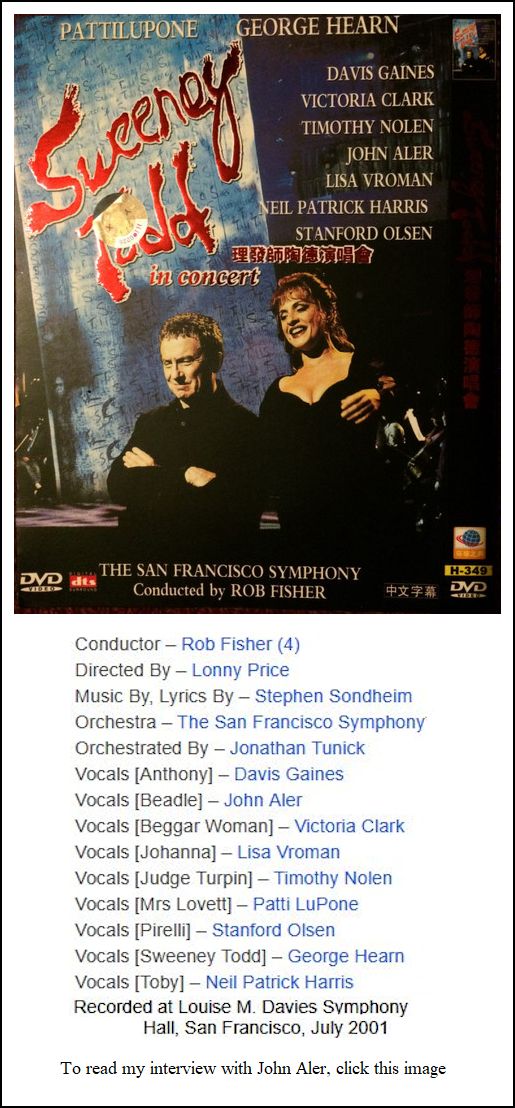

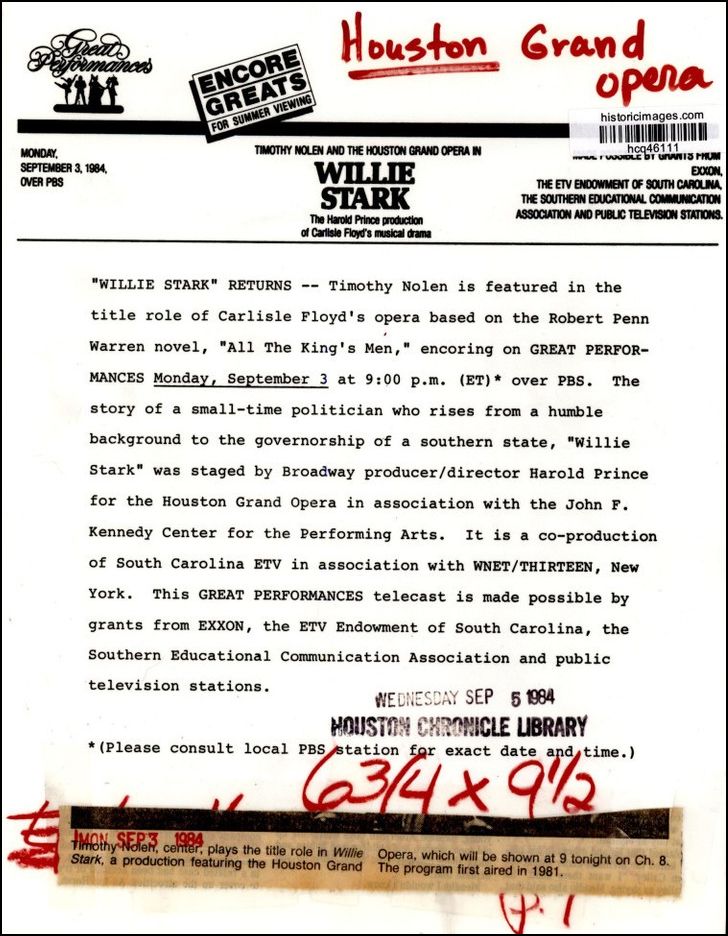

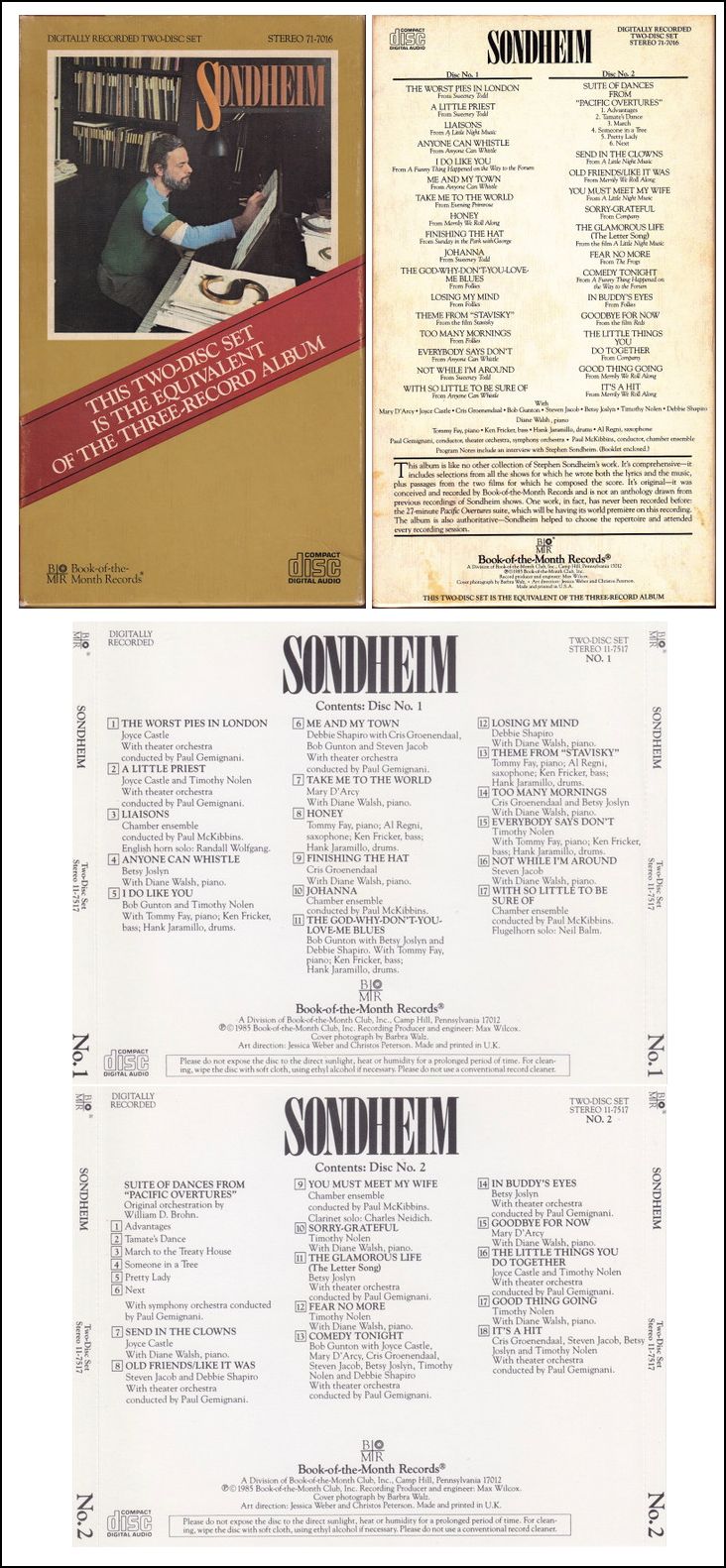

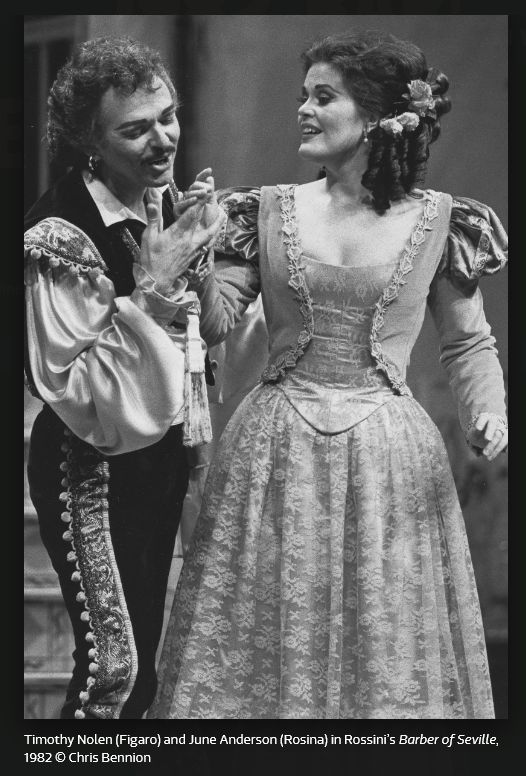

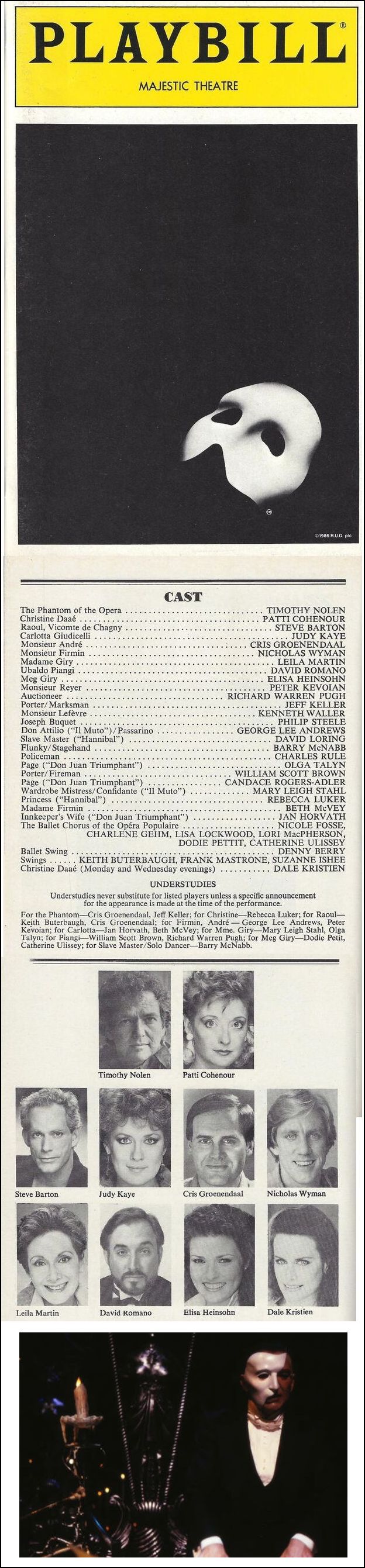

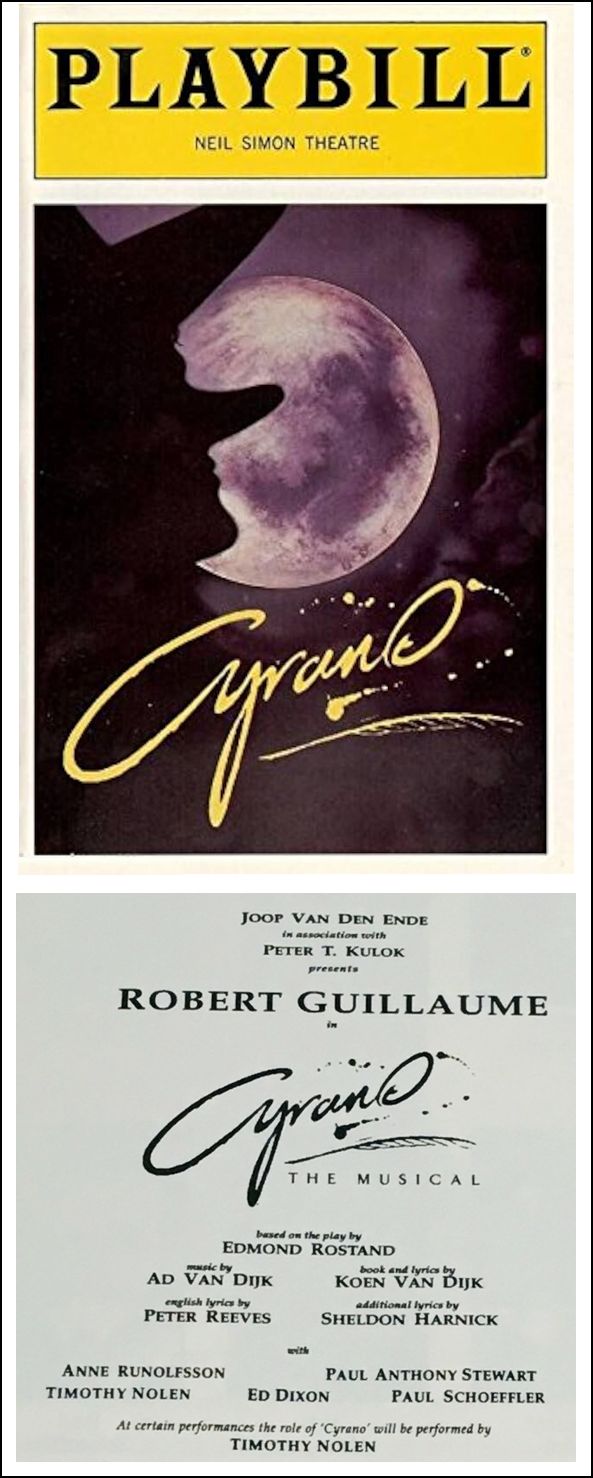

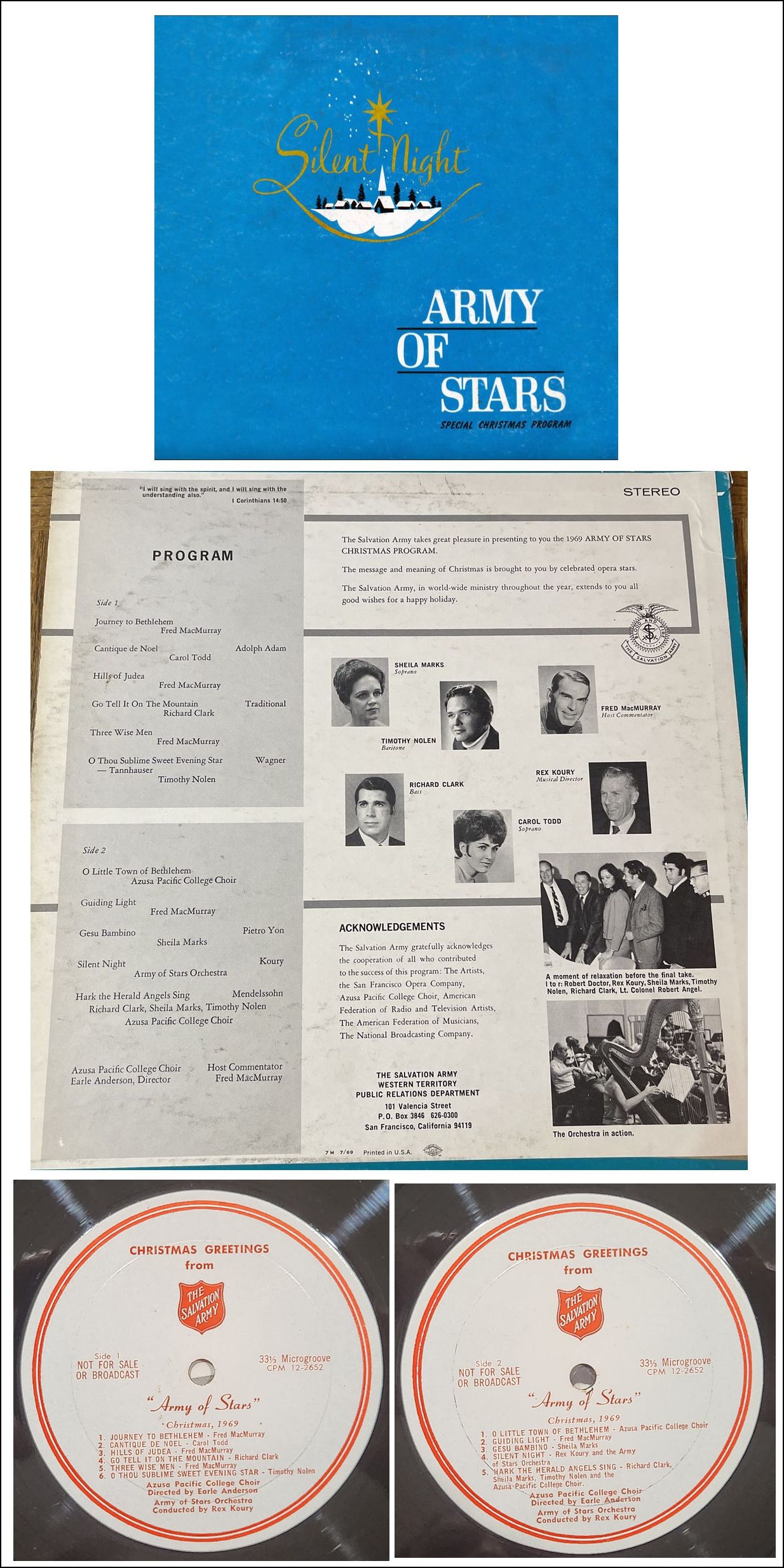

Timothy Nolen (July 9, 1941 – August 31, 2023) was an American actor and baritone who had an active career in operas, musicals, concerts, plays, and on television for over four decades. He was the second actor to play the title role in Andrew Lloyd Webber's The Phantom of the Opera on Broadway replacing Michael Crawford in October 1988. [Photo of program is shown below-right.] He left the production in March 1989 being replaced by operatic tenor and fellow Sweeney Todd and Phantom star Cris Groenendaal. Nolen notably portrayed the title role in the first operatic presentation of Stephen Sondheim's Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street at the Houston Grand Opera in 1984 and the role of Judge Turpin in a concert version of Sweeney Todd broadcast on PBS's Great Performances in 2001. Nolen was born in Rotan, Texas, and began his career appearing in small supporting roles with opera companies in the United States during the 1960s. He made his debut at the San Francisco Opera as the Officer in the United States premiere of Darius Milhaud's Christophe Colomb on October 5, 1968. He appeared in several supporting roles with the company through 1973, including Gregorio in Roméo et Juliette, Marullo in Rigoletto, Montano in Otello, Morales in Carmen, Ned Keene in Peter Grimes, Schaunard in La Bohème, Sciarrone in Tosca, and the Wigmaker in Ariadne auf Naxos among others. He then portrayed leading roles at the SFO including Figaro in The Barber of Seville (1976, with Frederica von Stade as Rosina), Dr. Malatesta in Don Pasquale (1980, with Geraint Evans in the title role), and Dr. Falke in Die Fledermaus (1990, with Patricia Racette as Rosalinde). In 1981, he created the title role in Willie Stark by Carlisle Floyd. [More details about that work are below in this box.] Nolen portrayed the title role in the first operatic presentations of Stephen Sondheim's Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street at the Houston Grand Opera and New York City Opera in 1984. He made his Broadway debut in 1985 as Doyle in the original production of Larry Grossman's Grind; a portrayal for which he received a Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Featured Actor in a Musical nomination. Nolen reprised the title role in Sweeney Todd at Chicago's Marriott Theatre in 1993, receiving a Joseph Jefferson Award nomination for his portrayal. He has since played Sweeney Todd in numerous productions, including at the Goodspeed Opera House. Nolen played the Comte de Guiche in Cyrano: The Musical (1994) on Broadway and later took over the role of Cyrano. [Photo of program is shown below-left.] In 2001, Nolen performed the role of Judge Turpin in a concert version of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street with the New York Philharmonic. The production was broadcast on PBS's Great Performances. Starring opposite him were George Hearn as Todd, Patti LuPone as Lovett, Davis Gaines as Anthony, and Neil Patrick Harris as Tobias. He reprised the role later that year in a production at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, with Bryn Terfel in the title role. [A full list of his appearances with Lyric Opera is in another box farther down on this webpage.] He later played Turpin in 2012 at the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis. In 2004, he returned to the title role at the New York City Opera opposite Elaine Paige as Mrs. Lovett. His television appearances include guest star appearances in The Sopranos, Wildfire, and Guiding Light. Nolen made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera on October 1, 1996 as Krusina in Bedřich Smetana's The Bartered Bride under the baton of James Levine. He has since returned to that house as Baron Zeta in The Merry Widow (2000–2001, with Plácido Domingo as Count Danilovich) and the One-Eyed Man in Die Frau ohne Schatten (2001–2002, with Deborah Voigt as the Empress). * * *

* *

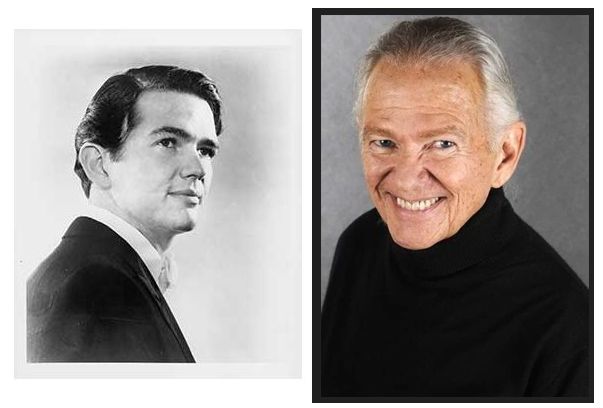

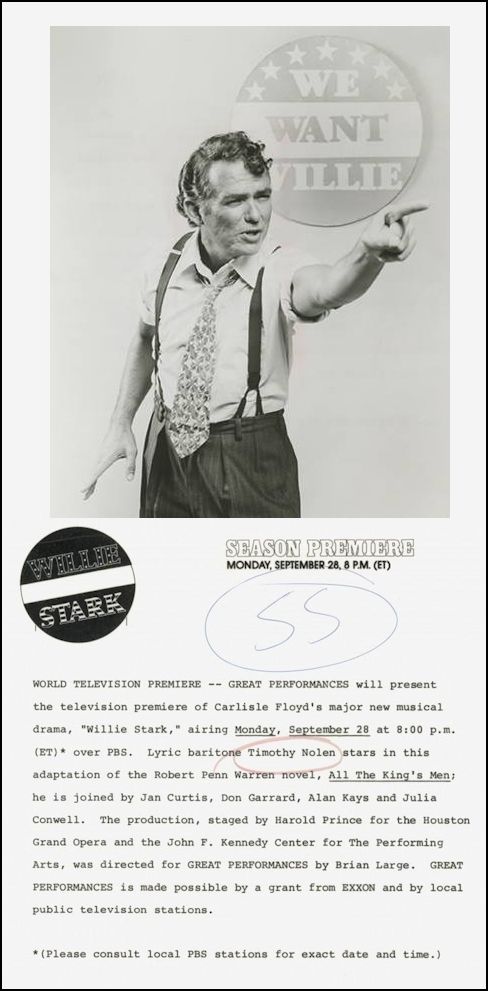

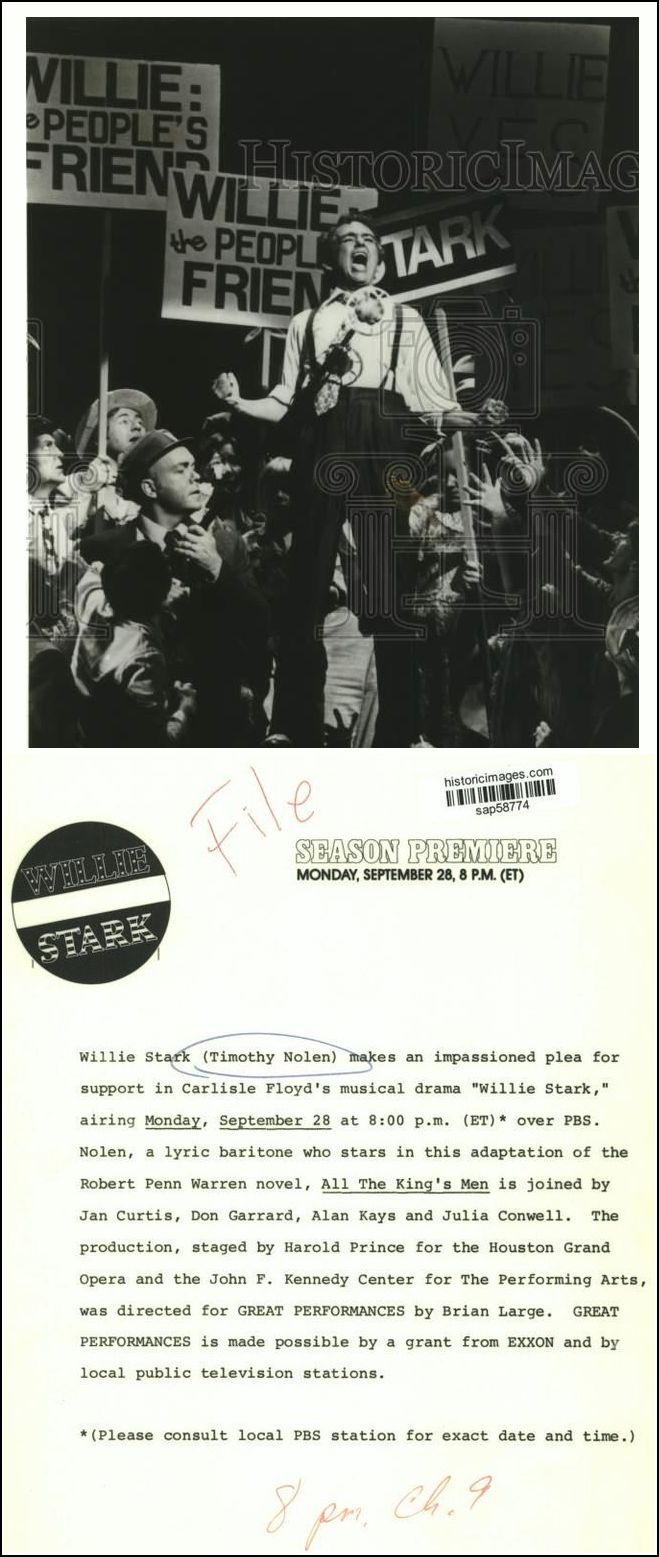

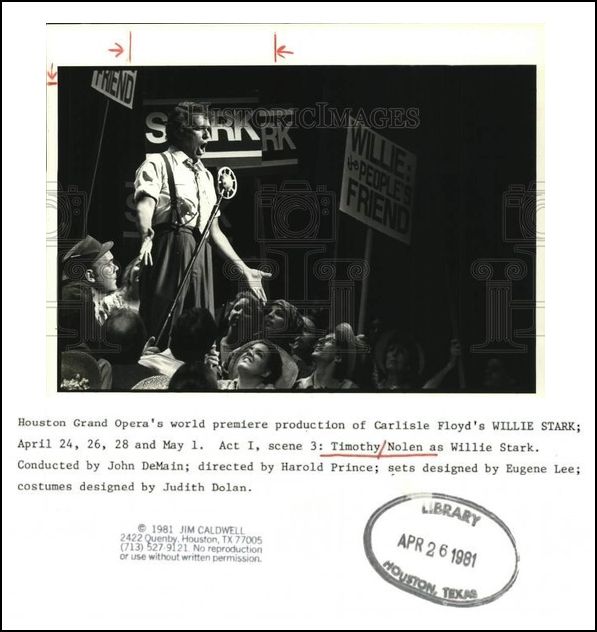

Willie Stark is an opera in three acts and nine scenes by Carlisle Floyd to his own libretto, after the 1946 novel All the King's Men by Robert Penn Warren, which in turn was inspired by the life of the Louisiana governor Huey Long. The opera was commissioned by the Houston Grand Opera, which premiered it on April 24, 1981, in a production directed by Harold Prince and conducted by John DeMain, with Timothy Nolen as the title character. Also in the cast were mezzo-soprano Jan Curtis, tenor Bruce Ford, and bass Don Garrard. The original production was dedicated to the American radio journalist Lowell Thomas. Floyd made cuts to the score for a television presentation of the opera, and the edited version was shown on US public television in September 1981. The opera was remounted in 2007 by the Louisiana State University Opera. The composer visited the university and advised on the production. The production was recorded and released on DVD, by Newport Classic. The work generated some small controversy among music critics, as

it draws upon elements of Broadway musical theater more than Floyd's

other more traditionally operatic works. The involvement of Broadway

director Harold Prince in the initial production contributed to the

emphasis of these elements of the work. In the years since its premiere,

this sort of blurring of boundaries between opera and Broadway musicals

has become commonplace. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

|

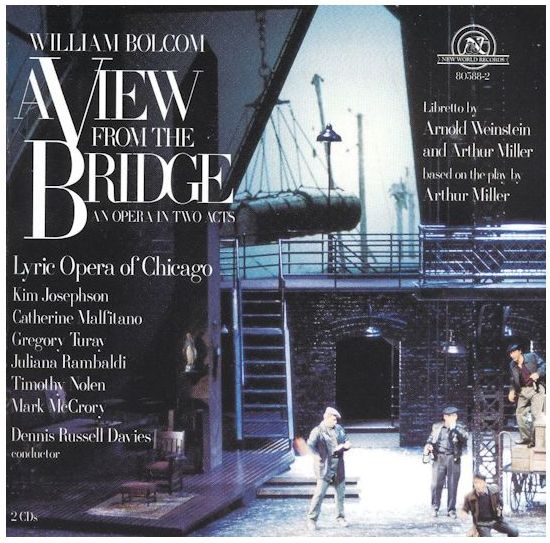

1974 - Peter Grimes (Ned Keene) with Vickers, Kubiak, Evans, Chookasian, Meredith; Bartoletti, Evans/Toms, Lepore 1976 - Cenerentola (Dandini) with Valentini-Terrani, Alva, Montarsolo, Azarmi, T. Hines, Romero; N. Rescigno, Ponnelle 1977 - Peter Grimes (Ned Keene) with Vickers, Kubiak, Meredith/Evans, Bainbridge, Voketaitis; Bartoletti, Evans, Toms - Manon Lescaut (Lescaut) with Chiara, Merighi, Montarsolo, Andreolli; Sanzogno/Bartoletti, De Lullo, Pizzi 1978 - Werther (Albert) with Kraus, Minton, Russell, Kunde, Ballam, Voketaitis; Giovaninetti, Samaritani 1979 - Love for Three Oranges (Pantaloon) with Suliotis, Little, Gill, Trussel, Halfvarson, Tajo, Kuhlmann, Mills, White; Prêtre, Chazalettes, Santicchi - Bohème (Schaunard) with Mitchell/Soviero, Shicoff/Prior, Zilio, Romero, Ramey, Tajo; Chailly, Frisell, Pizzi 1981 - Ariadne auf Naxos (Harlekin) with Meier/Rysanek, Johns, Welting, Schmidt/Minton, Gordon, Negrini; Janowski, Neugebauer, Messel 1982 - Fledermaus (Falke) with Brown, Langton, De Paolo, Jobin, Malas, Isaac, Madalin; Schaenen, Mansouri, O'Hearn, Tallchief 1983 - Cenerentola (Dandini) with Baltsa, Blake, Desderi, Harman-Gulick, Sharon Graham, Crafts; Ferro, Ponnelle/Asagaroff 1986/87 - Magic Flute (Papageno) with Araiza, Blegen, Salminen, Serra, Stewart, Taylor, White, Daniels; Slatkin, Everding, Zimmermann 1987/88 - Così fan tutte (Alfonso) with Te Kanawa/Griffel, Howells, McLaughlin, Hadley, Titus; Pritchard, Ponnelle/Asagaroff - L'Italiana in Algeri (Taddeo) with Baltsa, Blake, Alaimo, Wroblewski, Langton, Sharon Graham; Ferro, Ponnelle/Asagaroff 1989/90 - Fledermaus (Falke) with Daniels, Bonney, Rosenshein, Allen/Otey, Adams, Howells, Wilson; Rudel, Chazalettes, Santicchi 1990/91 - Magic Flute (Papageno) with Hadley, Mattila, Lloyd, Jo, Stewart, Pancella, Maultsby, Lawrence; Kuhn, Everding, Zimmermann 1992/93 - McTeague [Bolcom] (Marcus Schouler) with Heppner, Malfitano; D. R. Davies, Altman, Kuper 1994/95 - Candide (Businessman, Governor, Dr. Pangloss, Sage, 2nd Gambler/Police Chief, Voltaire) with Futral, P. Kraus, Pauley; Manahan, Prince/Masella, Dunham, Tallchief, Palumbo, Dufford 1995/96 - Don Pasquale (Malatesta) with Plishka, Swenson, Ford; Olmi, Montarsolo, Conklin 1996/97 - Ardis Krainik Gala with (among others) Horne, Manca di Nissa, Marton, Vaness, Anderson, Sylvester, Zajick; Barenboim (piano) 1997/98 - Peter Grimes (Ned Keene) with Heppner, Magee, Ellis, C. Cook, Travis; Elder, Copley, Toms, Palumbo 1998/99 - Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (Announcer/Trinity Moses) with Malfitano, Begley, Palmer, Aceto; Cambreling, D. Alden, Steinberg 1999/00 - Fledermaus (Falke) with Lott, Evans, Bottone, Allen, Del Carlo, Castle; Hager, Copley, Santicchi - A View from the Bridge [Bolcom] (Alfieri) with Malfitano, Josephson, Rambaldi/Bayrakdarian, Turay, McCrory; D.R. Davies, Galati, Loquasto

2001/02 - Stars of Lyric Opera at Millennium Park with (among others) Esperian, Fleming, Heppner, Gallo, Malfitano; Davis - Street Scene [Weill] (Harry Easter) with Malfitano, Cangelosi, P. Kraus; R. Buckley, Pountney, Fielding 2002/03 - Sweeney Todd [Sondheim] (Judge Turpin) with Terfel, Greenawald, Gunn, Bottone; Gemignani, Armfield, Thompson 2003/04 - Regina [Blitzstein] (Oscar Hubbard) with Malfitano, Woods, Travis, P. Blackwell, C. Shelton; Mauceri, Newell, Culbert 2004/05 - A Wedding [Bolcom] (William Williamson) with Malfitano, Hadley, Harries, Flanigan, Lawrence, Doss; D.R. Davies, Altman, Wagner |

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 16, 1981. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.