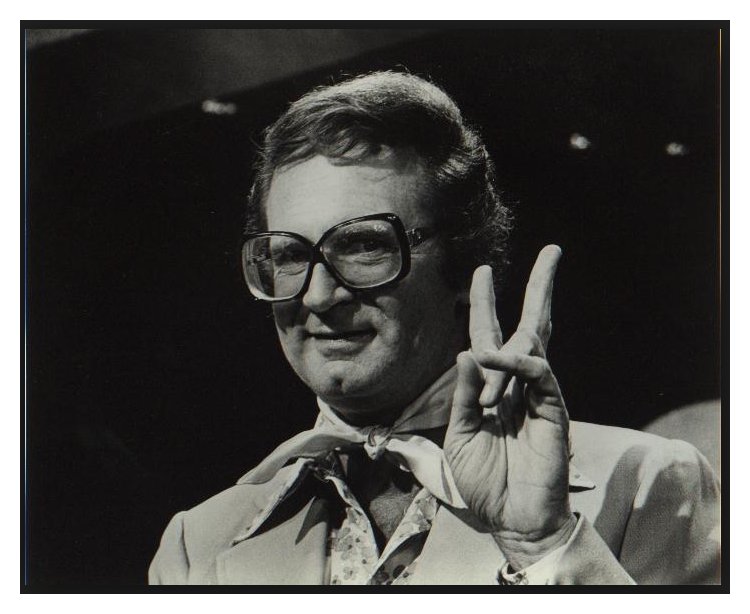

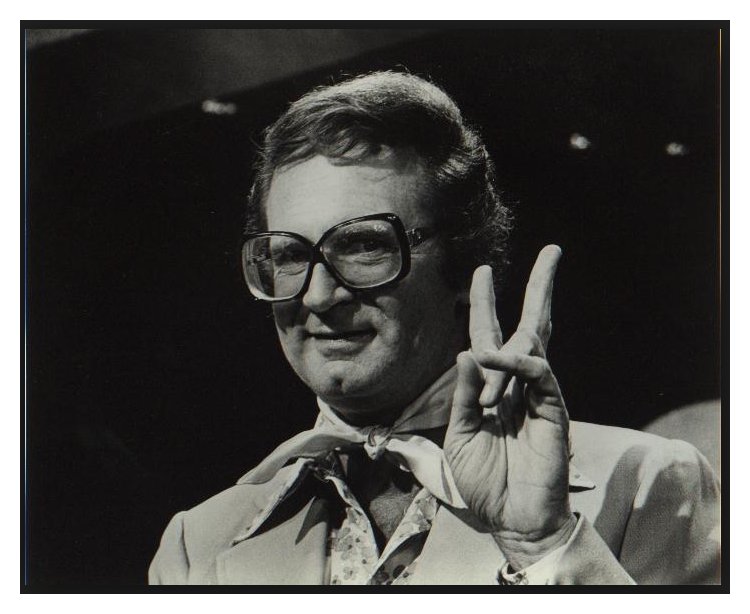

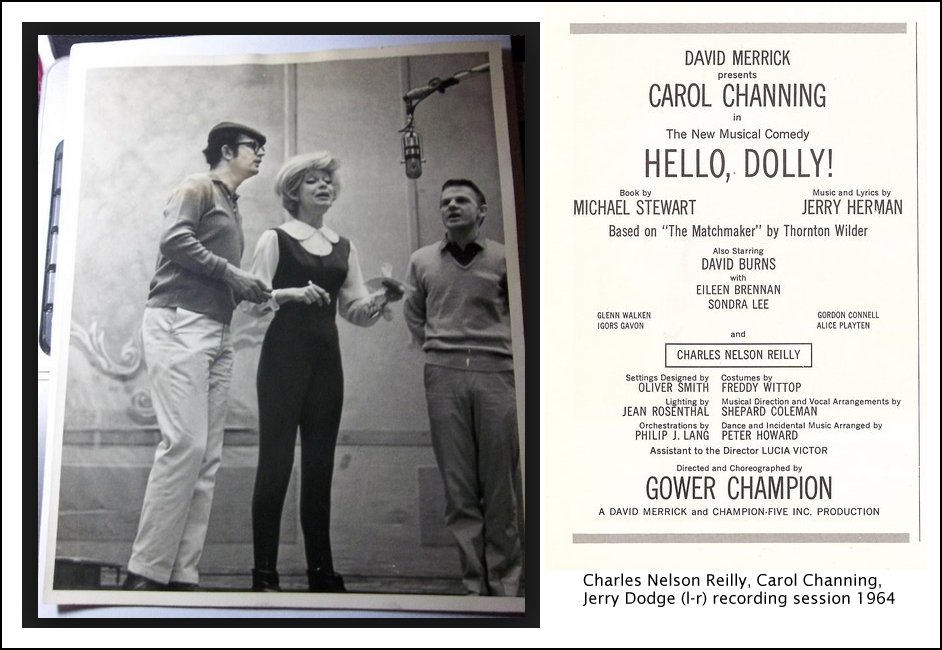

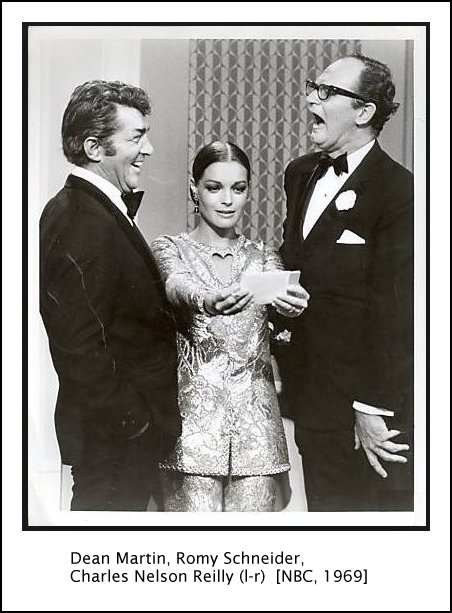

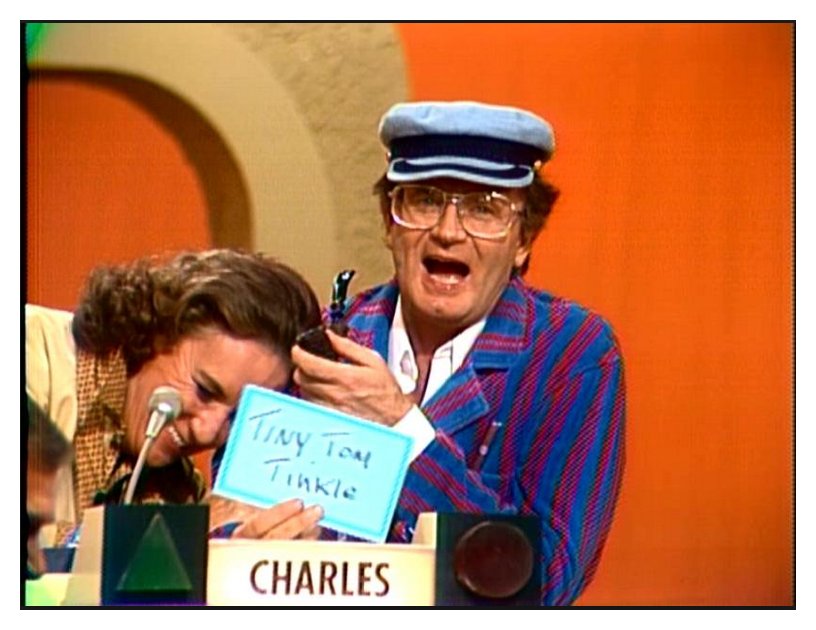

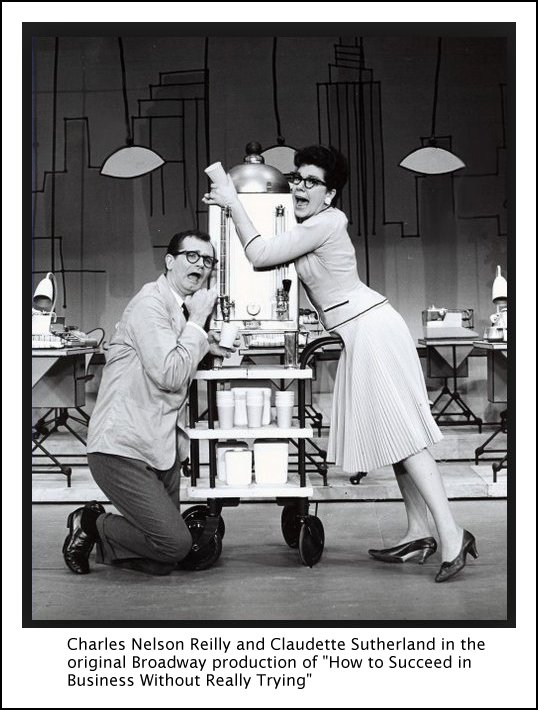

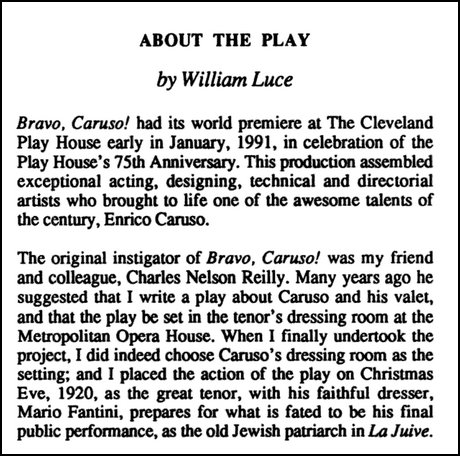

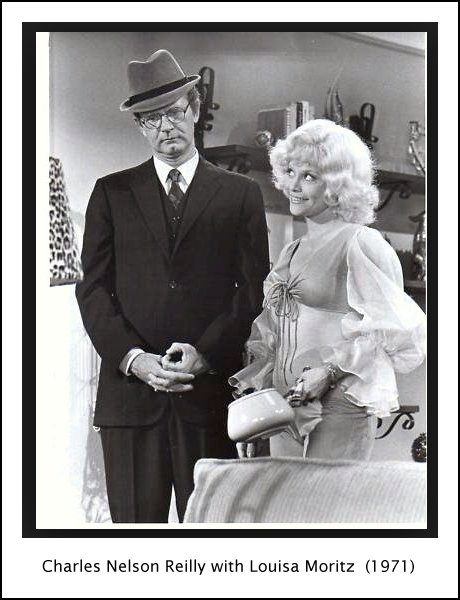

| Obituaries Charles Nelson Reilly, 76; Tony-winning actor, TV game show regular May 29, 2007|Valerie J. Nelson | Los Angeles Times Staff Writer [Text only - photos added for this website presentation] Charles Nelson Reilly, whose persona as a wacky game show panelist and talk show guest overshadowed his serious work as a director and Tony-winning actor, has died. He was 76. Reilly, a longtime resident of Beverly Hills, died Friday of complications from pneumonia at UCLA Medical Center, said Paul Linke, who directed Reilly's one-man show "Save It for the Stage: The Life of Reilly." "The average person thinks of him as being on 'The Match Game.' That was a mixed blessing for him," Linke told The Times on Monday. "One of the reasons I was so motivated to get his show out there was because I wanted people to recognize that this was a heavyweight talent." When a Times reporter visited his home in 2000, Reilly displayed an opera review that referred to him as "Charles Nelson Reilly of 'Hollywood Squares' fame." "It's like a scarlet letter," Reilly yowled in his high-pitched, nasal voice. Wearing his trademark ascot and oversized glasses, Reilly made a near-record 97 appearances on "The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson," often making ribald ripostes. After a "Tonight Show" guest who was talking about Shakespeare dismissed Reilly's attempt to join the conversation, he silenced her by delivering Hamlet's "the play's the thing" monologue straight, with depth and passion, the New York Observer reported in 2001. He broke through on Broadway in 1961, winning a Tony for playing the insidious nephew Bud Frump in the original production of "How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying." Reilly also received Tony nominations for his role in "Hello, Dolly!" in 1964, and for directing a revival of "The Gin Game" with Julie Harris in 1997.

Reilly often directed plays that starred Harris, including "The Belle of Amherst," a 1977 one-woman play about Emily Dickinson that remained one of his proudest achievements. "He's a wonderful actor but never gets enough chance to do it," Harris told the Times in 2000. "He's taught me a lot about theater. It's his insight into the personal idiosyncrasies of human beings. He's attuned to small details -- the pieces of the puzzle that make up the whole picture." Reilly's close friend Burt Reynolds said in a 1991 Times article that he thought Reilly's reputation as the perpetual jester had worked against him in Hollywood. "We have a thing in this town that if you are enormously witty and gregarious, you can't be very deep. There's something wrong with a society that says, 'You're the wit, but you're not the teacher.' People just haven't seen him in this arena," Reynolds said. A well-regarded acting instructor, Reilly moved to Florida in 1979 to teach at the Burt Reynolds Institute. Reilly also coached Liza Minnelli, Bette Midler, Lily Tomlin and Christine Lahti and ran an acting school in North Hollywood. In his one-man show, which would be his final work, Reilly told the story of his life, which began Jan. 13, 1931, in New York City. The play's name came from the phrase his mother often said when her son spoke: "Save it for the stage." In 2006, the show was made into the movie "The Life of Reilly."  He was the only child of the former Signe Elvera Nelson and Charles Joseph

Reilly, who designed outdoor advertising for Paramount Pictures. After his

father had a nervous breakdown, partly brought on because his wife made him

turn down a job offer from Walt Disney, he was institutionalized, Linke said.

He was the only child of the former Signe Elvera Nelson and Charles Joseph

Reilly, who designed outdoor advertising for Paramount Pictures. After his

father had a nervous breakdown, partly brought on because his wife made him

turn down a job offer from Walt Disney, he was institutionalized, Linke said.Reilly and his mother moved to Hartford, Conn., to live with 10 relatives, all of whom spoke Swedish, in an apartment that had only cold water. "Eugene O'Neill could never begin to get near all this," Reilly said in the 2000 Times article. At 9, he got the lead in the school play, and a teacher told his mother that Reilly was the only true actor she had ever known, the Observer reported. When he was 13, he and a friend survived a circus fire in Hartford that killed more than 165 people. It was the last time he would sit in a theater as an audience member, Reilly repeatedly said. By 18, he had moved to New York and was soon studying with Uta Hagen and her husband, Herbert Berghof, at their acting school. Classmates included Jack Lemmon, Charles Grodin, Geraldine Page and Hal Holbrook. Reilly never tried to hide his homosexuality, and frequently cracked double-entendres on television about being gay. He got a job as a night mail boy at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and tried to get hired by NBC, but a producer told him "that they don't allow queers on television," Linke said. "Charles' response was, 'It didn't bother me. I knew in my heart his words weren't true,' " Linke said. Later, Reilly would count how many game show appearances he would make in a week -- once it was 27 -- and consider it his revenge. When he first came to California to co-star on television in "The Ghost and Mrs. Muir" in 1968, he stepped off the plane and said of the 70-degree weather: " 'How long has this been going on?' He said he'd been cold his whole life until then," Linke said. Reilly made more money in one or two TV appearances with Dean Martin than he would in a year of performing on Broadway, so he stayed, Linke said. Reilly went on to make many guest appearances in sitcoms and was a regular on "Laugh-In." In the late 1960s, Reilly bought his Beverly Hills home and also owned a 34-foot cabin cruiser that he kept in Marina del Rey. "The world is a slightly less funny place now," Linke said. "He made people laugh along the way, and that's a legacy that lives on long after the game shows." Reilly is survived by Patrick Hughes, his companion of more than 25 years. |

|

Chicago Opera Theater`s `Cinderella` Makes Rossini

Fit Like A Glass Slipper

April 25, 1988. By John von Rhein, Music critic. Chicago Tribune If Chicago Opera Theater was feeling the pinch of having to produce more opera within a shorter time span than ever before, no strain was evident in the company`s season finale, Rossini`s “Cinderella,” which had its first performance Saturday at the Athenaeum Theatre. Those who admired the high spirits and authentic musical style that have marked the Opera Theater`s previous forays into Rossini`s comic repertory will not be disappointed with “Cinderella.” The production, beautifully sung by a youthful and attractive ensemble and buoyantly staged by Charles Nelson Reilly, makes a charming addition to the cycle. Regular operagoers will draw comparisons with Lyric Opera`s most recent Rossini effort, “L`Italiana in Algeri.” Here it must be admitted that the Opera Theater enjoys a sizable advantage over the Lyric, because the Rossini comedies really work best when presented in the language of the audience in small theaters that allow the words to be easily projected and clearly understood. They do not require major international casts to make the kind of effect the composer intended. Why has “Cinderella”-or “La Cenerentola,” to revert to the original Italian title-failed to achieve the enormous popularity of Rossini`s earlier buffa, “Il Barbiere di Siviglia”? Certainly its score is equally fine, and in some respects it is even superior. Perhaps the fairy-tale plot of a poor servant girl wooed and won by a handsome prince is stretched rather too far here, but then, the repertory is full of operas that shamelessly make comic mountains out of narrative molehills. One thing, however, is certain. The Opera Theater is presenting more of Rossini`s score than most Rossinians probably have ever heard, this despite deleting all music not written by Rossini that has found its way into various corrupt editions. True, this makes for a long evening in the theater, but conductor Louis Salemno wields such a knowing, firmly propulsive hand, and elicits such crisp playing from the chamber orchestra, that the 3 1/4 hours of “Cinderella” pass very pleasantly indeed. The Opera Theater cast is strong from top to bottom. I first heard Stella Zambalis in the title role last year in St. Louis, where she was wonderful. This time allowances had to be made for the fact that she was singing through a case of flu so severe it forced cancellation of the Sunday matinee. (That performance now has been rescheduled for May 8.) However, only in “Non piu mesta” did one notice that Zambalis was not in her best vocal form. The warmth and flexibility of her wide-ranging mezzo, and her touching portrayal of the character, won all hearts. To find a young Rossini tenor as sweet of voice and as accomplished of technique as Glenn Siebert is good news indeed these days. His confidently sung Ramiro blended nicely with Zambalis` voice in the tender duets. James Rensink was a dandy Dandini. If his coloratura was less than precise, this rakish courtier clearly relished his princely masquerade; every amusing flourish was drawn to perfection. John Fiorito, the Don Magnifico, managed to avoid the usual buffo overkill as the opera`s serio-comic figure. Janis Knox and Kathryn Hartgrove added much to the prevailing high spirits as the not-so-ugly stepsisters. Rossini`s Cinderella has a human godfather rather than a fairy godmother; the character was nobly sung by Greg Ryerson. The simple, storybook-cutout sets, borrowed from Texas Opera Theater, were a good match for the bright costumes of Kerry Fleming. Ruth and Thomas Martin`s English translation adhered to the general sense, if not always the literal meaning, of the libretto. “Cinderella” plays through May 8. `CINDERELLA` Comic opera in three acts by Rossini, presented by Chicago Opera Theater April 23 at the Athenaeum Theatre, 2936 N. Southport Ave. Conducted by Louis Salemno, directed by Charles Nelson Reilly, set designs by Peter Dean Beck, costumes by Kerry Fleming, lighting by Michael S. Philippi, artistic supervision by Alan Stone. Length of performance: 3:15. Repeat performances at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday and May 4, 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday, 3 p.m. Sunday and May 8. Tickets $14 to $36. Phone 663-0048. |

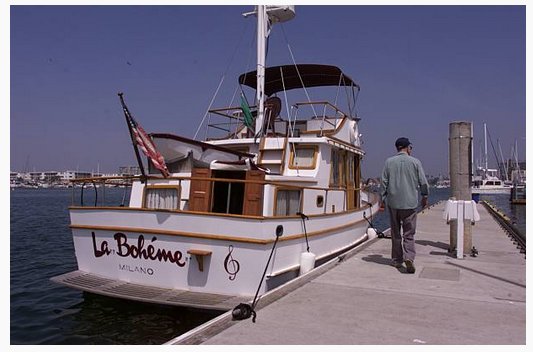

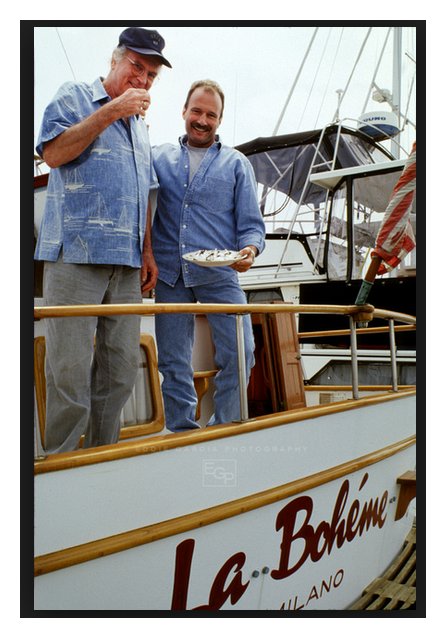

As may or may not be generally known, Reilly was very much into opera,

and his knowledge stemmed from both practical experience and genuine love

of the form. He even named his boat the La Bohéme. (Note that the

accent is incorrect, but, as shown in the photo at right, that is what appears

on the back of the watercraft! He even says the name as ‘la

boe-aim’ rather than ‘la boe-ehm’.)

As may or may not be generally known, Reilly was very much into opera,

and his knowledge stemmed from both practical experience and genuine love

of the form. He even named his boat the La Bohéme. (Note that the

accent is incorrect, but, as shown in the photo at right, that is what appears

on the back of the watercraft! He even says the name as ‘la

boe-aim’ rather than ‘la boe-ehm’.) BD: Were you involved in the designing of the sets?

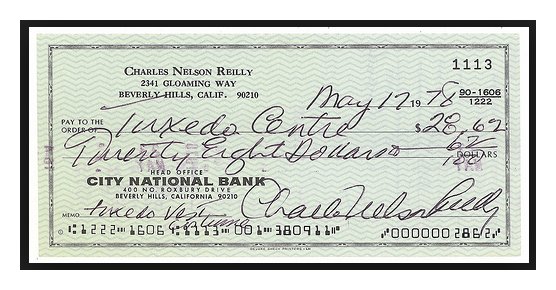

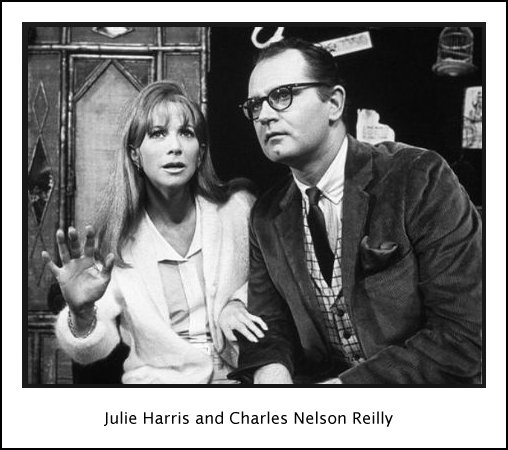

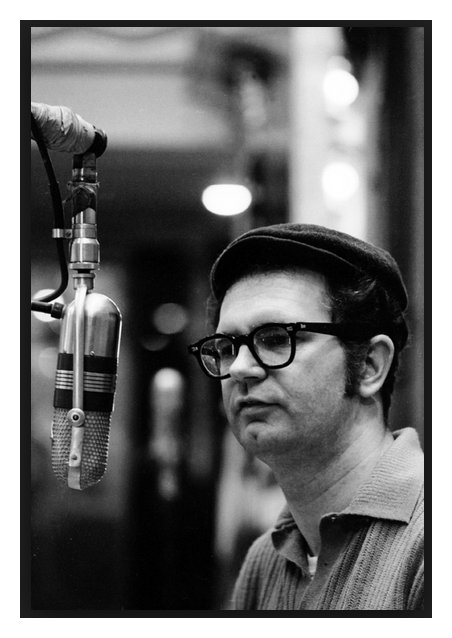

BD: Were you involved in the designing of the sets? CNR: Sure. Why not? I have such a strange

career. I leave here after the matinee — and

the party, I might add — so the 10 o’clock flight gets

me in at 1 o’clock in LA. That same day, Monday, I do five Hollywood Squares. Now nobody was

ever a stage director and game player in the same year, let alone on the

same day, and you can go a little crazy. [Musing to himself]

“Now what am I today? Am I a panelist, a teacher

or a director?” I’m a professor, too, you know,

and you get so confused. You can’t possibly have clothes for all these

parts [notice his check at left].

I’m getting a little old and a little tired, but my first love has always

been the musical theater, and mainly opera. I just spoke to my friend

today, Arthur Matera. We were boyhood friends in Hartford, and his

wife, Barbara, is the very celebrated woman who handles all the costumes.

She makes Sutherland’s

clothes, Barbara Matera, Limited, from London. We’ve been friends

for fifty-some odd years. Arthur first got me interested in opera when

he was in West Hartford, Connecticut. I was in his living room when

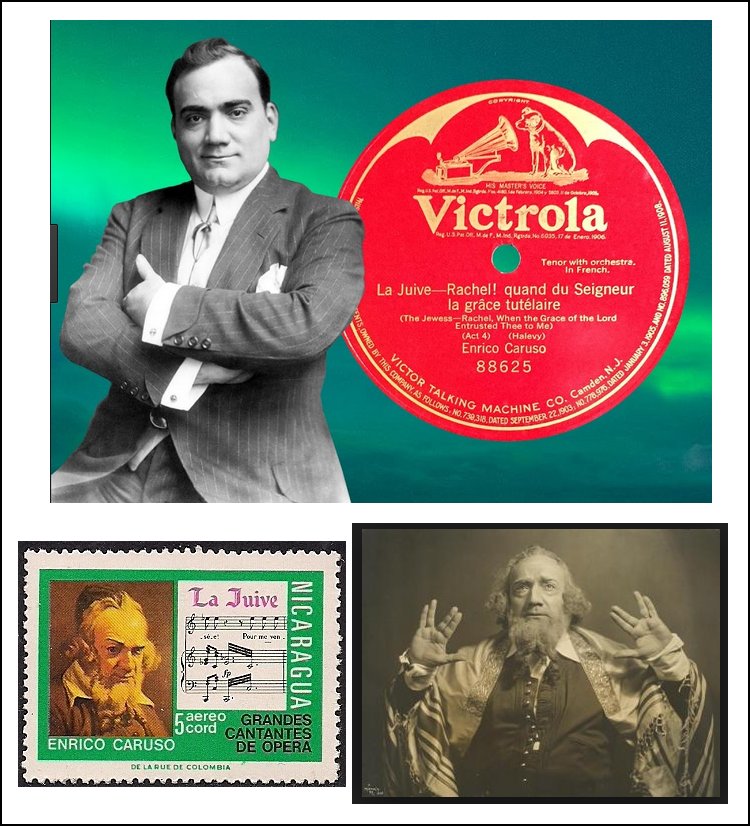

he was about nine, and we acted out the whole of Tosca to the Gigli/Caniglia recording.

I got very taken by that, and I seriously studied to be a singer with the

teacher of Teresa Stich-Randall, Ivan Velikanoff, but I couldn’t free my

top. What happens is now that my top is free, I’m too old! [Laughs]

CNR: Sure. Why not? I have such a strange

career. I leave here after the matinee — and

the party, I might add — so the 10 o’clock flight gets

me in at 1 o’clock in LA. That same day, Monday, I do five Hollywood Squares. Now nobody was

ever a stage director and game player in the same year, let alone on the

same day, and you can go a little crazy. [Musing to himself]

“Now what am I today? Am I a panelist, a teacher

or a director?” I’m a professor, too, you know,

and you get so confused. You can’t possibly have clothes for all these

parts [notice his check at left].

I’m getting a little old and a little tired, but my first love has always

been the musical theater, and mainly opera. I just spoke to my friend

today, Arthur Matera. We were boyhood friends in Hartford, and his

wife, Barbara, is the very celebrated woman who handles all the costumes.

She makes Sutherland’s

clothes, Barbara Matera, Limited, from London. We’ve been friends

for fifty-some odd years. Arthur first got me interested in opera when

he was in West Hartford, Connecticut. I was in his living room when

he was about nine, and we acted out the whole of Tosca to the Gigli/Caniglia recording.

I got very taken by that, and I seriously studied to be a singer with the

teacher of Teresa Stich-Randall, Ivan Velikanoff, but I couldn’t free my

top. What happens is now that my top is free, I’m too old! [Laughs] BD: We’re always

moving, aren’t we?

BD: We’re always

moving, aren’t we?

CNR: Yes, they can if they work hard and put the time

in.

CNR: Yes, they can if they work hard and put the time

in. BD: I assume, though, that you want operas to be more

than just stand-and-sing affairs.

BD: I assume, though, that you want operas to be more

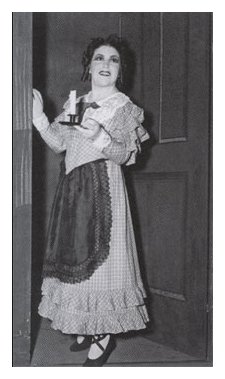

than just stand-and-sing affairs. CNR: What impressed

me about her as a child and all through my life is that she’s the only one

who really uses the word to the fullest. There was a Polish tenor,

Jan Kiepura, who, when he sang in Italy, the Italians would say, “We

love the way you said that.” It’s interesting,

isn’t it? Albanese spoke very well, and she said whenever she was tired

on the stage, she would never sacrifice the word, but would save her voice

at times if she was not up to the pacing. But the word, she said,

is the whole thing. Listen to sixty versions of the scene of Bohème where she comes in and

he lights the candle, and then she says, “Buona sera,” and

goes out. If you were an actor, you fulfill that moment and say, “Good

night.” Now if you listen to every recording,

Albanese is the only one that says, “Good night”

as if there’s no more music in the part [photo at right]. The others all

anticipate they’ve got three and half acts to go. She says, “Good

night,” and it’s over because at that moment it’s over.

It’s a real ‘good night’, and it knocks you over when you hear a real ‘good

night’ instead of a vocalizing, “I’ll be back in a

moment,” with one foot on the threshold. I saw

Rysanek once at the old Met thirty years ago in Aïda. I was sitting way at

the top, and she walked into the room in the first scene. She walked

into the room, and the whole balcony leaned a foot forward. Aïda

always shows up at four minutes after eight, but she just walked on.

She didn’t walk on her hands, or sway side to side posturing. She wasn’t

a soprano in an opera; she was a woman who worked for a queen. She was

a handmaiden, and she simply walked in a room. My teacher says everyone

puts their pants on the same way. She just walked in the room.

I saw something very interesting about two years ago at Bohème in Los Angeles, presented

by the New York City Opera. I can stage the boys’ chorus in the second

act faster than any other director. Do you know how you do it?

When they meet you they all smile at you, and you say, “All

you boys with braces go on the right, and those without braces go on the

left.” It only takes a minute. I know all

the tricks. But anyway, there was a stage filled with activity.

There was the complete cast, Parpignol, and everybody had a toy and everybody

had a big banner. Musetta was in a white sled with a muff. Sonja

Henie never had such an outfit! [Sonja

Henie (8 April 1912 – 12 October 1969) was a Norwegian figure skater and film

star. She was a three-time Olympic Champion (1928, 1932, 1936) in Ladies'

Singles, a ten-time World Champion (1927–1936) and a six-time European Champion

(1931–1936). Henie won more Olympic and World titles than any other ladies'

figure skater. At the height of her acting career, she was one of the highest

paid stars in Hollywood and starred in a series of box-office hits.]

There were a million things going on, but the audience was looking at the

extreme right of the stage in the corner. It was the whole audience.

I checked. The whole audience, in truth, was looking at a corner because

a UCLA boy was a super, and the stage manager told him, “Go

out in the Café Momus set and dry the glasses.”

So this boy went out. He was told to dry the glasses, and what did

he do? He dried the glasses. The whole audience looked at that

because it was the only natural thing, the only honest thing on the stage,

and it lit up like you wouldn’t believe. You heard people talk about

it at intermission. In opera it’s what you do. In Traviata I have her take two pills.

I stole that from a Camille. She has two pills knotted in her handkerchief,

and she takes the two pills while the baritone is singing. She takes

the water from the well and takes the pills. The audience talks about

those pills at intermission. You don’t have to be a genius. She’s

got tuberculosis, so the doctor in the first act maybe gave her a pill.

Those are the things the audience will remember, and they free the singer.

Yesterday I had a wonderful scene in Cinderella

where Cinderella, who’s delicious, carries this big pan of hot water to

bathe the feet of the sisters and the father in the morning. You can

see the steam, so the three of them are sitting in the hot water, and they’re

sitting in this hot water because the family’s in hot water. [Laughs]

They’re going to be bankrupt! He’s going to go to prison for abusing

this child and not giving her a full birthright. It’s true.

That’s the original story. So the three of them are singing and sitting

in this pan of water, and it’s steaming, and it’s very funny. I got

the idea this morning that I’ll have the mezzo who plays Cinderella be asphyxiated

for a few minutes from the smoke. She has nothing to sing there, so

she can be asphyxiated for few minutes. [Both have a huge laugh]

I think it’s wonderful! That’s the fun of that opera, but they sang

better because they were really doing something. They were bathing

their feet, and for a minute they forgot this dotted note and that technique

of vocalism, and it soared for a minute. It’s not about the music;

it’s about life. The words can free you, and they’ll sing better.

It’ll be glorious if you really say, “Good night.”

CNR: What impressed

me about her as a child and all through my life is that she’s the only one

who really uses the word to the fullest. There was a Polish tenor,

Jan Kiepura, who, when he sang in Italy, the Italians would say, “We

love the way you said that.” It’s interesting,

isn’t it? Albanese spoke very well, and she said whenever she was tired

on the stage, she would never sacrifice the word, but would save her voice

at times if she was not up to the pacing. But the word, she said,

is the whole thing. Listen to sixty versions of the scene of Bohème where she comes in and

he lights the candle, and then she says, “Buona sera,” and

goes out. If you were an actor, you fulfill that moment and say, “Good

night.” Now if you listen to every recording,

Albanese is the only one that says, “Good night”

as if there’s no more music in the part [photo at right]. The others all

anticipate they’ve got three and half acts to go. She says, “Good

night,” and it’s over because at that moment it’s over.

It’s a real ‘good night’, and it knocks you over when you hear a real ‘good

night’ instead of a vocalizing, “I’ll be back in a

moment,” with one foot on the threshold. I saw

Rysanek once at the old Met thirty years ago in Aïda. I was sitting way at

the top, and she walked into the room in the first scene. She walked

into the room, and the whole balcony leaned a foot forward. Aïda

always shows up at four minutes after eight, but she just walked on.

She didn’t walk on her hands, or sway side to side posturing. She wasn’t

a soprano in an opera; she was a woman who worked for a queen. She was

a handmaiden, and she simply walked in a room. My teacher says everyone

puts their pants on the same way. She just walked in the room.

I saw something very interesting about two years ago at Bohème in Los Angeles, presented

by the New York City Opera. I can stage the boys’ chorus in the second

act faster than any other director. Do you know how you do it?

When they meet you they all smile at you, and you say, “All

you boys with braces go on the right, and those without braces go on the

left.” It only takes a minute. I know all

the tricks. But anyway, there was a stage filled with activity.

There was the complete cast, Parpignol, and everybody had a toy and everybody

had a big banner. Musetta was in a white sled with a muff. Sonja

Henie never had such an outfit! [Sonja

Henie (8 April 1912 – 12 October 1969) was a Norwegian figure skater and film

star. She was a three-time Olympic Champion (1928, 1932, 1936) in Ladies'

Singles, a ten-time World Champion (1927–1936) and a six-time European Champion

(1931–1936). Henie won more Olympic and World titles than any other ladies'

figure skater. At the height of her acting career, she was one of the highest

paid stars in Hollywood and starred in a series of box-office hits.]

There were a million things going on, but the audience was looking at the

extreme right of the stage in the corner. It was the whole audience.

I checked. The whole audience, in truth, was looking at a corner because

a UCLA boy was a super, and the stage manager told him, “Go

out in the Café Momus set and dry the glasses.”

So this boy went out. He was told to dry the glasses, and what did

he do? He dried the glasses. The whole audience looked at that

because it was the only natural thing, the only honest thing on the stage,

and it lit up like you wouldn’t believe. You heard people talk about

it at intermission. In opera it’s what you do. In Traviata I have her take two pills.

I stole that from a Camille. She has two pills knotted in her handkerchief,

and she takes the two pills while the baritone is singing. She takes

the water from the well and takes the pills. The audience talks about

those pills at intermission. You don’t have to be a genius. She’s

got tuberculosis, so the doctor in the first act maybe gave her a pill.

Those are the things the audience will remember, and they free the singer.

Yesterday I had a wonderful scene in Cinderella

where Cinderella, who’s delicious, carries this big pan of hot water to

bathe the feet of the sisters and the father in the morning. You can

see the steam, so the three of them are sitting in the hot water, and they’re

sitting in this hot water because the family’s in hot water. [Laughs]

They’re going to be bankrupt! He’s going to go to prison for abusing

this child and not giving her a full birthright. It’s true.

That’s the original story. So the three of them are singing and sitting

in this pan of water, and it’s steaming, and it’s very funny. I got

the idea this morning that I’ll have the mezzo who plays Cinderella be asphyxiated

for a few minutes from the smoke. She has nothing to sing there, so

she can be asphyxiated for few minutes. [Both have a huge laugh]

I think it’s wonderful! That’s the fun of that opera, but they sang

better because they were really doing something. They were bathing

their feet, and for a minute they forgot this dotted note and that technique

of vocalism, and it soared for a minute. It’s not about the music;

it’s about life. The words can free you, and they’ll sing better.

It’ll be glorious if you really say, “Good night.” CNR: It’s got to be right even.

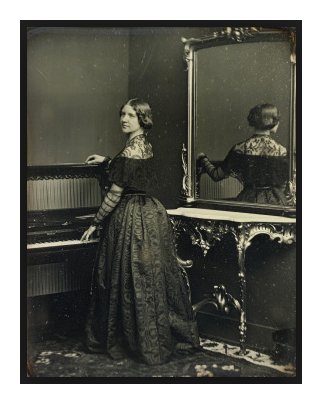

CNR: It’s got to be right even. Johanna Maria Lind (6 October 1820 – 2 November 1887), better known as

Jenny Lind, was a Swedish opera singer, often known as the "Swedish Nightingale".

One of the most highly regarded singers of the 19th century, she performed

soprano roles in opera in Sweden and across Europe, and undertook an extraordinarily

popular concert tour of America beginning in 1850. She was a member of

the Royal Swedish Academy of Music from 1840.

Johanna Maria Lind (6 October 1820 – 2 November 1887), better known as

Jenny Lind, was a Swedish opera singer, often known as the "Swedish Nightingale".

One of the most highly regarded singers of the 19th century, she performed

soprano roles in opera in Sweden and across Europe, and undertook an extraordinarily

popular concert tour of America beginning in 1850. She was a member of

the Royal Swedish Academy of Music from 1840.Lind became famous after her performance in Der Freischütz in Sweden in 1838. Within a few years, she had suffered vocal damage, but the singing teacher Manuel García saved her voice. She was in great demand in opera roles throughout Sweden and northern Europe during the 1840s, and was closely associated with Felix Mendelssohn. After two acclaimed seasons in London, she announced her retirement from opera at the age of 29. In 1850, Lind went to America at the invitation of the showman P. T. Barnum. She gave 93 large-scale concerts for him and then continued to tour under her own management. She earned more than $350,000 from these concerts, donating the proceeds to charities, principally the endowment of free schools in Sweden. With her new husband, Otto Goldschmidt, she returned to Europe in 1852 where she had three children and gave occasional concerts over the next two decades, settling in England in 1855. From 1882, for some years, she was a professor of singing at the Royal College of Music in London. There are no recordings of Lind's voice. She is believed to have made an early phonograph recording for Thomas Edison, but in the words of the critic Philip L. Miller, "Even had the fabled Edison cylinder survived, it would have been too primitive, and she too long retired, to tell us much". |

BD: Maybe she knew where the cameras were?

BD: Maybe she knew where the cameras were? BD: You haven’t reset

the numbers?

BD: You haven’t reset

the numbers? BD:

Why does everybody want to be an opera singer? Why don’t people want

to be Cabaret singers?

BD:

Why does everybody want to be an opera singer? Why don’t people want

to be Cabaret singers? CNR: I have a boat called ‘La

Bohéme’. It costs more than my house.

It’s rotting, and the boat’s the worst thing in the world, but I love it,

and I have a good time. I make all the commercials and the training

films for the Coast Guard. I’m a member of the Coast Guard Auxiliary,

and if you go learn how to make a boat, I’m the teacher, believe it or not.

Ain’t that funny? I should direct Vasco da Gama’s opera... [L'Africaine is a grand opera in five acts, the last work

of composer Giacomo Meyerbeer. The French libretto by Eugène

Scribe deals with fictitious events in the life of the Portuguese explorer

Vasco da Gama. Meyerbeer's working title for the opera was, in fact,

Vasco de Gama. The opera had

its first performance by the Paris Opéra at the Salle Le Peletier

on 28 April 1865.] I do these things nobody knows about.

It’s mad. It’s a strange life. But anyway, my friends

come, and about two years ago, Jean Simmons, the actress, wanted a party

on my boat. It was to be at four o’clock in the afternoon.

Now Marina del Rey is the largest marina in the world with privately owned

boats. On weekdays it’s not very busy, there’s nobody out, and this

was a dreary day. She wanted to have a party for the three men who

played her son in The Thorn Birds.

So I make supper at home, and I bring it on the boat, or if there’s just

two or three people I cook it on the boat. You can cook on the boat,

but I like to make it nice at home and then heat it on the boat because food

is important to me. So anyway my friend, Abigail van Buren came, too.

She’s funny. She’s a wonderful woman. So they all came along

with a couple of other friends, so it was eight or nine people at 4 o’clock

on a very dreary day. I took the boat out. What I do is go up

and down and the channel to see the other boats. Then we go to the

ocean, and it’s usually a little rough... So we don’t

do that. It’s just the sight-seeing in the channel to see hundreds

of beautiful boats. They’re from New Zealand, from Spain, they’re not

all from Malibu. We go around and have drinks, and it’s very nice.

Another boat was passing us, a smaller four seat dingy was passing us on

the side, and as it passed I heard the first act duet of Freni and Pavarotti

in La Bohème. They

had a generous tape recorder on the back seat, and I recognized it, of course,

as it went by. So that’s that. An hour and half later, about

5:30, we came back from the ocean, and they were following us this time.

We were the only two boats around on that dreary day. There were four

young people on it. The girl looked like Valerie Harper, and they were

screaming maniacally at the top of their voices. I thought they recognized

Jean Simmons and the three boys. Two of them were famous, beautiful

young men, and Abigail van Buren was there, but they were screaming and trying

to catch up to us. It turned out that her mother had died, and they

went to put the ashes of the mother in the ocean. In the Will, the

mother stipulated that La Bohème

play. After they did that, they were following us, and my boat goes

by, and says right on the back, La Bohéme. That to me is unbelievable.

So I gave them everything on my boat that said La Bohéme. They

got everything — every place mat, every napkin

— and I said, “In memory of your mother.”

Why was it just our two boats and no others? Isn’t that an amazing

story? It’s not a sad story, but it’s an interesting one.

CNR: I have a boat called ‘La

Bohéme’. It costs more than my house.

It’s rotting, and the boat’s the worst thing in the world, but I love it,

and I have a good time. I make all the commercials and the training

films for the Coast Guard. I’m a member of the Coast Guard Auxiliary,

and if you go learn how to make a boat, I’m the teacher, believe it or not.

Ain’t that funny? I should direct Vasco da Gama’s opera... [L'Africaine is a grand opera in five acts, the last work

of composer Giacomo Meyerbeer. The French libretto by Eugène

Scribe deals with fictitious events in the life of the Portuguese explorer

Vasco da Gama. Meyerbeer's working title for the opera was, in fact,

Vasco de Gama. The opera had

its first performance by the Paris Opéra at the Salle Le Peletier

on 28 April 1865.] I do these things nobody knows about.

It’s mad. It’s a strange life. But anyway, my friends

come, and about two years ago, Jean Simmons, the actress, wanted a party

on my boat. It was to be at four o’clock in the afternoon.

Now Marina del Rey is the largest marina in the world with privately owned

boats. On weekdays it’s not very busy, there’s nobody out, and this

was a dreary day. She wanted to have a party for the three men who

played her son in The Thorn Birds.

So I make supper at home, and I bring it on the boat, or if there’s just

two or three people I cook it on the boat. You can cook on the boat,

but I like to make it nice at home and then heat it on the boat because food

is important to me. So anyway my friend, Abigail van Buren came, too.

She’s funny. She’s a wonderful woman. So they all came along

with a couple of other friends, so it was eight or nine people at 4 o’clock

on a very dreary day. I took the boat out. What I do is go up

and down and the channel to see the other boats. Then we go to the

ocean, and it’s usually a little rough... So we don’t

do that. It’s just the sight-seeing in the channel to see hundreds

of beautiful boats. They’re from New Zealand, from Spain, they’re not

all from Malibu. We go around and have drinks, and it’s very nice.

Another boat was passing us, a smaller four seat dingy was passing us on

the side, and as it passed I heard the first act duet of Freni and Pavarotti

in La Bohème. They

had a generous tape recorder on the back seat, and I recognized it, of course,

as it went by. So that’s that. An hour and half later, about

5:30, we came back from the ocean, and they were following us this time.

We were the only two boats around on that dreary day. There were four

young people on it. The girl looked like Valerie Harper, and they were

screaming maniacally at the top of their voices. I thought they recognized

Jean Simmons and the three boys. Two of them were famous, beautiful

young men, and Abigail van Buren was there, but they were screaming and trying

to catch up to us. It turned out that her mother had died, and they

went to put the ashes of the mother in the ocean. In the Will, the

mother stipulated that La Bohème

play. After they did that, they were following us, and my boat goes

by, and says right on the back, La Bohéme. That to me is unbelievable.

So I gave them everything on my boat that said La Bohéme. They

got everything — every place mat, every napkin

— and I said, “In memory of your mother.”

Why was it just our two boats and no others? Isn’t that an amazing

story? It’s not a sad story, but it’s an interesting one.

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

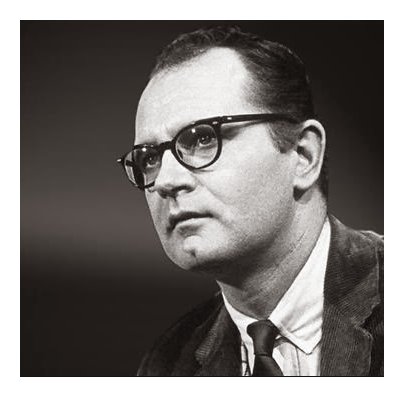

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 17, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two days later. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.