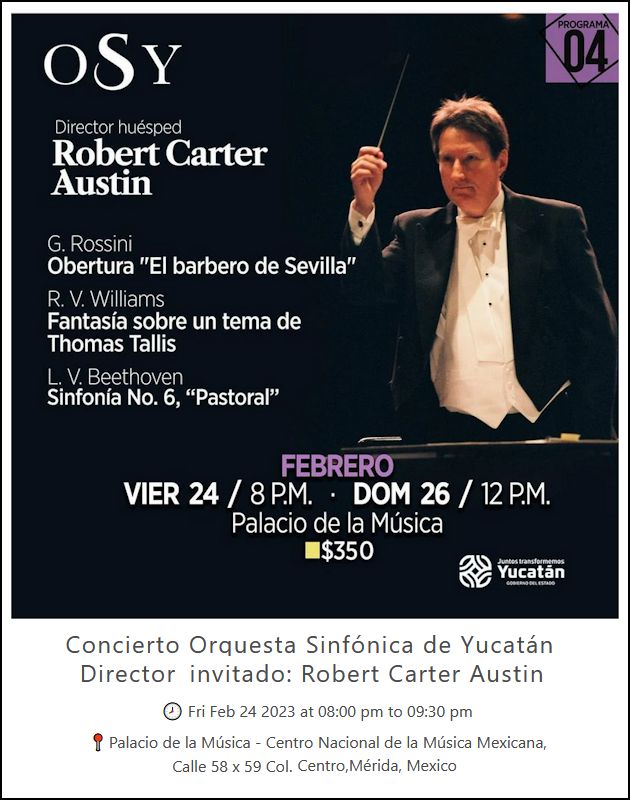

A native of Tennessee, Robert Carter Austin is currently

in his twenty-sixth season as Music Director of the Las Colinas Symphony

Orchestra. Maestro Austin has an unusually diverse educational background

for a classical musician, including a Bachelor of Science degree

from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a Diploma (with

Distinction) in Computer Science from Cambridge University, and a

Master of Musical Arts degree from Stanford University.

A native of Tennessee, Robert Carter Austin is currently

in his twenty-sixth season as Music Director of the Las Colinas Symphony

Orchestra. Maestro Austin has an unusually diverse educational background

for a classical musician, including a Bachelor of Science degree

from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a Diploma (with

Distinction) in Computer Science from Cambridge University, and a

Master of Musical Arts degree from Stanford University.

Maestro Austin’s first professional appointment was as Artistic Director of the Chattanooga Opera in 1974. He added the post of Artistic Director of the Southern Regional Opera in Birmingham, Alabama in 1978. Shifting his focus to symphonic music in 1981, he became Music Director of the Cheyenne Symphony Orchestra in Wyoming, before coming to Texas in 1985 as Music Director of the East Texas Symphony Orchestra in Tyler. He has served as Music Director of the Garland Symphony Orchestra since 1988, of the Las Colinas Symphony Orchestra since 1991, and of Symphony Arlington since 2000.

In frequent demand as a guest conductor, Maestro Austin has led performances with opera companies and symphony orchestras in eleven states in the U.S. His international credits include performances with the Chursächische Philharmonie, Südwestdeutsche Philharmonie, and Orchester des Nordharzer Städtebundtheaters in Germany; the Florence Sinfonietta, Orchestra Sinfonica Regionale del Molise, Milano Classico, and L’Offerta Musicale in Italy; the National Orchestras of Ukraine, Ecuador, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, and the Philippines; and orchestras in France, Spain, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Mexico, and China. Upcoming engagements for Maestro Austin include the Orchestra Sinfonica Città di Grosseto in Italy and the Amazonas Filarmonica in Brazil.

Off the podium, Maestro Austin describes himself as an avid skier, a closet country music fan, and a notorious oenophile. His wife, Dr. Kathryn Gamble, is the Director of Veterinary Medicine at Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago, Illinois.

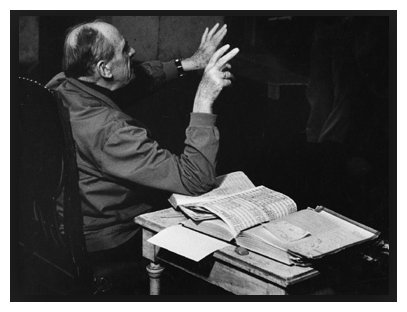

Walter Felsenstein (30 May 1901 – 8 October

1975) was an Austrian theater and opera director. He

was one of the most important exponents of textual accuracy, and

gave productions in which dramatic and musical values were exquisitely

researched and balanced. In 1947 he created the Komische

Oper in East Berlin, where he worked as director until his death.

Walter Felsenstein (30 May 1901 – 8 October

1975) was an Austrian theater and opera director. He

was one of the most important exponents of textual accuracy, and

gave productions in which dramatic and musical values were exquisitely

researched and balanced. In 1947 he created the Komische

Oper in East Berlin, where he worked as director until his death.

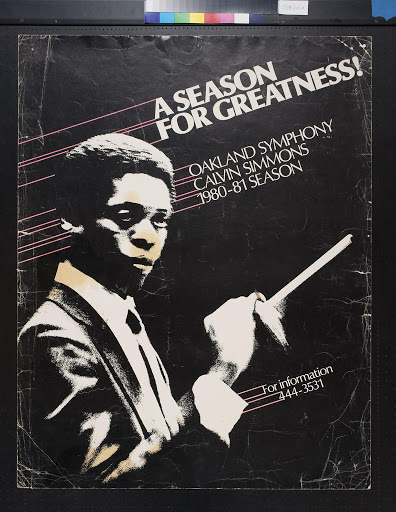

Simmons

was born in San Francisco, California. At the age

of 9, he entered the Bay Area's musical scene and began

living his dream of becoming a world-class musician. He

had been taught the piano from an early age by his mother, Matty.

By age 11, he was conducting the San Francisco Boys Chorus,

started by Madi Bacon, of which he had been a member. Bacon

gave him the early artistic freedom to assist with the chorus

that would serve him and others for years. He was assistant

conductor with the San Francisco Opera from 1972 to 1975,

winning the Kurt Herbert Adler Award.

Simmons

was born in San Francisco, California. At the age

of 9, he entered the Bay Area's musical scene and began

living his dream of becoming a world-class musician. He

had been taught the piano from an early age by his mother, Matty.

By age 11, he was conducting the San Francisco Boys Chorus,

started by Madi Bacon, of which he had been a member. Bacon

gave him the early artistic freedom to assist with the chorus

that would serve him and others for years. He was assistant

conductor with the San Francisco Opera from 1972 to 1975,

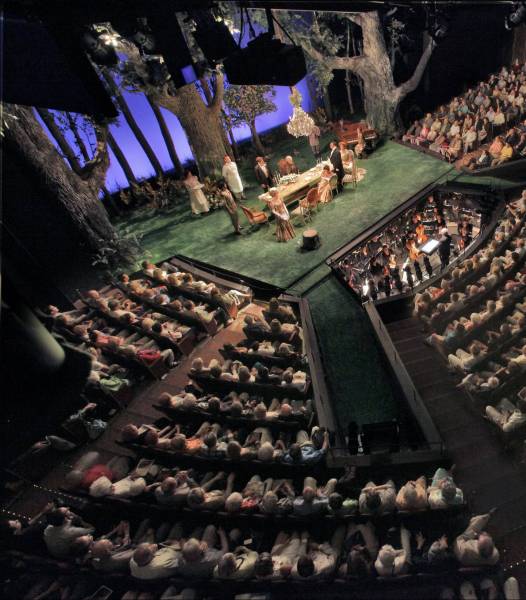

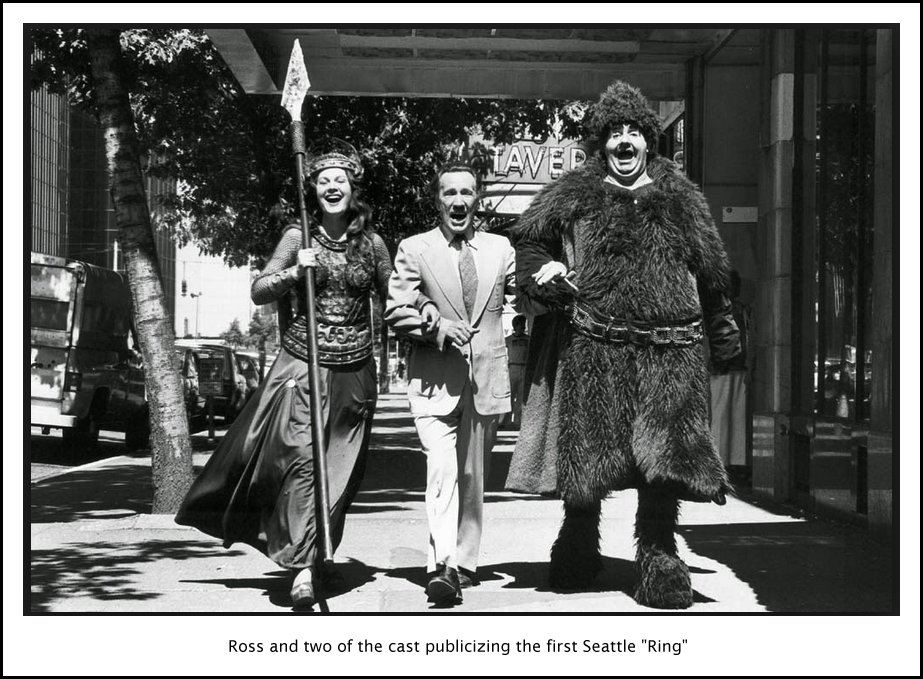

winning the Kurt Herbert Adler Award.  John Balme (born 1946) is an American conductor, opera

manager and pianist. He served as general director of Boston Lyric Opera

from 1979 to 1989 and the Lake George Opera Festival from 1988 to 1992.

He was also music director of the Liederkranz Foundation of the City

of New York from 1984 to 1998. He has participated as conductor, assistant

conductor, and/or producer in over 300 productions and has appeared

as a guest conductor throughout the United States. He is best known

for producing and conducting of the complete Ring Cycle of Richard

Wagner for the Boston Lyric Opera in Boston and New York City in 1982

and 1983.

John Balme (born 1946) is an American conductor, opera

manager and pianist. He served as general director of Boston Lyric Opera

from 1979 to 1989 and the Lake George Opera Festival from 1988 to 1992.

He was also music director of the Liederkranz Foundation of the City

of New York from 1984 to 1998. He has participated as conductor, assistant

conductor, and/or producer in over 300 productions and has appeared

as a guest conductor throughout the United States. He is best known

for producing and conducting of the complete Ring Cycle of Richard

Wagner for the Boston Lyric Opera in Boston and New York City in 1982

and 1983.