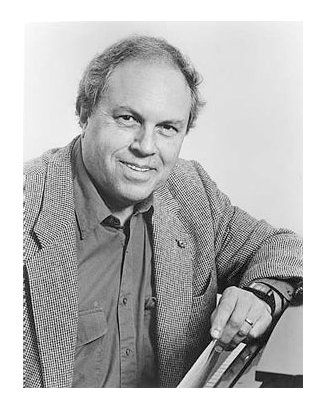

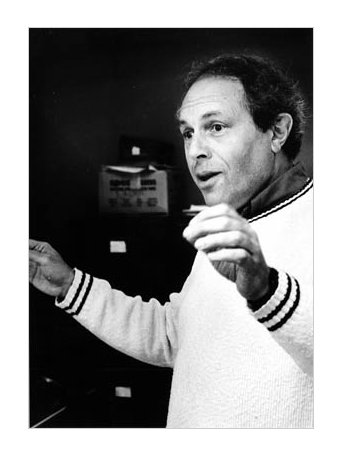

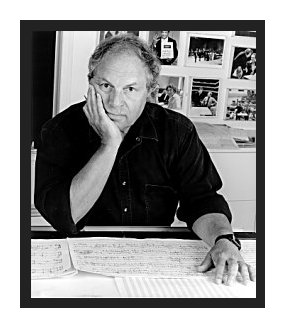

| Jacob Druckman (June 26, 1928 -

May 24, 1996) was a unique voice among contemporary composers and the soundscapes

he created reflected the manysidedness of the music of our time. He was also

a teacher, a conductor, and a musical catalyst, a highly effective spokesman

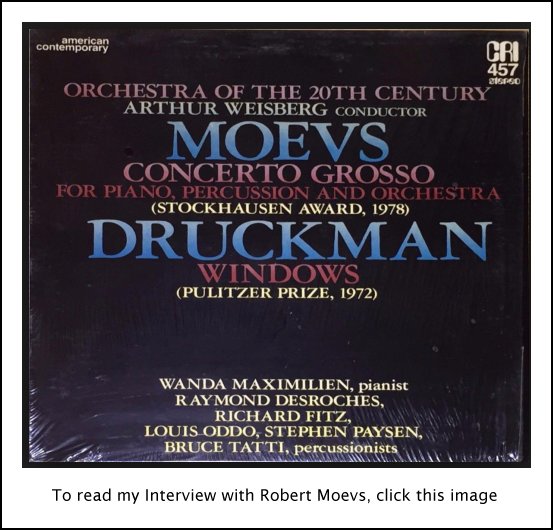

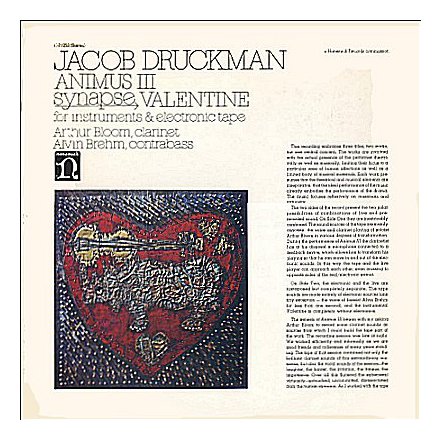

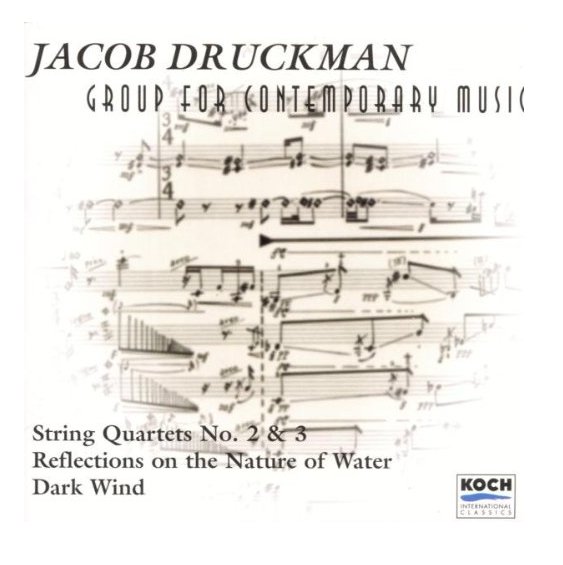

for contemporary music and musicians. Druckman's own output contained works in the large and small media. In addition to his orchestra works, he wrote for ensembles (with or without voice) and for solo instruments. One of the most prominent of contemporary American composers, Jacob Druckman was born in Philadelphia in 1928. After early training in violin and piano, he enrolled in the Juilliard School in 1949, studying composition with Bernard Wagenaar, Vincent Persichetti, and Peter Mennin. In 1949 and 1950 he studied with Aaron Copland at Tanglewood; later, he continued his studies at the Ecole Normale de Musique in Paris (1954-55). Critic Mark Swed has written, "At the heart of the works of Jacob Druckman lies the bold, sure, and often arrestingly physical dramatic gesture....Yet Druckman's scores have always exhibited another characteristic as well: that of careful structure, built with meticulous attention to detail. The process of integrating these two sides of his character...has been a consistent factor throughout the composer's development." Druckman produced a substantial list of works embracing orchestral, chamber, and vocal media, and did considerable work with electronic music. In 1972, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Windows, his first work for large orchestra. Among his other numerous grants and awards were a Fulbright Grant in 1954, a Thorne Foundation award in 1972, Guggenheim Grants in 1957 and 1968, and the Publication Award from the Society for the Publication of American Music in 1967. Organizations that commissioned his music included Radio France (Shog, 1991); the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (Brangle, 1989); the New York Philharmonic (Concerto for Viola and Orchestra, 1978; Aureole, 1979); the Philadelphia Orchestra (Counterpoise, 1994); the Baltimore Symphony (Prism, 1980); the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra (Mirage, 1976); the Juilliard Quartet (String Quartet No. 2, 1966); the Koussevitzky Foundation in the Library of Congress (Windows, 1972); IRCAM (Animus IV, 1977); and numerous others. He also composed for theater, films, and dance. Notable musicians who have recorded his works include David Zinman, Wolfgang Sawallisch, Zubin Mehta, Leonard Slatkin, Dawn Upshaw, Jan DeGaetani, and the American Brass Quintet. Druckman taught at the Juilliard School, Bard College, and Tanglewood; in addition he was director of the Electronic Music Studio and Professor of Composition at Brooklyn College. He was also associated with the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in New York City. In the spring of 1982, he was Resident-In-Music at the American Academy in Rome; in April of that year, he was appointed composer-in-residence with the New York Philharmonic, where he served two two-year terms and was Artistic Director of the HORIZONS music festival. In the last years of his life, Druckman was Professor of Composition at the School of Music at Yale University. -- Throughout this page, names which

are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

JD: Part of it is, certainly, reacting to the

zeitgeist. I don’t know whether

it’s a development or a regression. [Both laugh] In these years,

in some ways it feels like we are taking giant steps backwards, but these

are changes that are not arbitrary. I’ve lived long enough to know about

such things. I lived through the sixties, which I think of as a great

time of change. You may have heard a lot of talking that I did and

that others did — a little bit of it, as a matter of

fact, even in agreement with what I was saying, occasionally. But back

when I was the composer-in-residence with the New York Philharmonic, I did

a series of festivals that were based on the notion that there was, indeed,

a major change in the aesthetics of the musical world somewhere that happened

in the mid- to late sixties, and I’m still thoroughly convinced that the

history books of the future are going to point to those years, as they do

to the early sixteen hundreds, which is the beginning of the Baroque Era

that there were turnings around. Having lived through that period of

those changes in the sixties, I remember feeling like the child in the story

The Emperor’s New Clothes, that

my God, I’m all alone! I see the truth and there’s nobody else that’s

seeing what I’m seeing. I discovered as the years went by that I was

not alone, and that so many other composers were having the same kinds of

feeling, of a kind of epiphany, a revelation of some truth.

JD: Part of it is, certainly, reacting to the

zeitgeist. I don’t know whether

it’s a development or a regression. [Both laugh] In these years,

in some ways it feels like we are taking giant steps backwards, but these

are changes that are not arbitrary. I’ve lived long enough to know about

such things. I lived through the sixties, which I think of as a great

time of change. You may have heard a lot of talking that I did and

that others did — a little bit of it, as a matter of

fact, even in agreement with what I was saying, occasionally. But back

when I was the composer-in-residence with the New York Philharmonic, I did

a series of festivals that were based on the notion that there was, indeed,

a major change in the aesthetics of the musical world somewhere that happened

in the mid- to late sixties, and I’m still thoroughly convinced that the

history books of the future are going to point to those years, as they do

to the early sixteen hundreds, which is the beginning of the Baroque Era

that there were turnings around. Having lived through that period of

those changes in the sixties, I remember feeling like the child in the story

The Emperor’s New Clothes, that

my God, I’m all alone! I see the truth and there’s nobody else that’s

seeing what I’m seeing. I discovered as the years went by that I was

not alone, and that so many other composers were having the same kinds of

feeling, of a kind of epiphany, a revelation of some truth.

JD: Yes, sometimes pleasantly. [Laughs]

I remember once Gerald Arpino, the choreographer with the Joffrey Ballet,

had done several of my pieces, and at one point I was telling him about a

new piece. I actually brought him over to my apartment in New York to

hear a tape of it. He listened and thought, and he said, “Tell me, have

you done anything else?” I said, “Well, there’s one other piece I did,

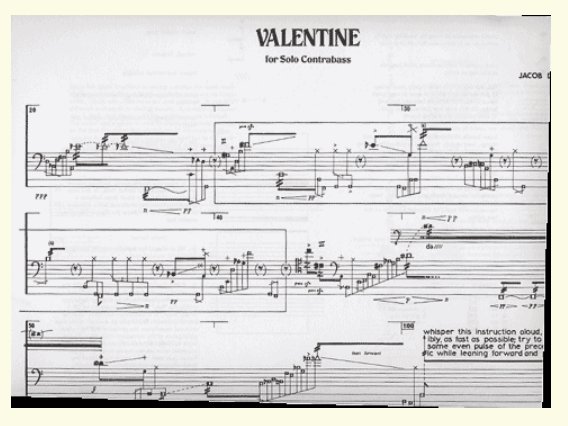

but it’s nothing you could use” and talked about this piece for solo contrabass

called Valentine. He listened

to it and he said, “Oh, my God! This is the piece!” And sure

enough, he did it, and it was the best of our so-called collaborations.

They weren’t really collaborations...

JD: Yes, sometimes pleasantly. [Laughs]

I remember once Gerald Arpino, the choreographer with the Joffrey Ballet,

had done several of my pieces, and at one point I was telling him about a

new piece. I actually brought him over to my apartment in New York to

hear a tape of it. He listened and thought, and he said, “Tell me, have

you done anything else?” I said, “Well, there’s one other piece I did,

but it’s nothing you could use” and talked about this piece for solo contrabass

called Valentine. He listened

to it and he said, “Oh, my God! This is the piece!” And sure

enough, he did it, and it was the best of our so-called collaborations.

They weren’t really collaborations... BD: Did he take over for Bill Kraft out there?

BD: Did he take over for Bill Kraft out there?

JD: I can’t think of any sorrows! [Laughs]

Maybe for the singers... I adore writing for the voice, and the more

I write the more I realize that everything is an imitation or glorification

of that. I’m so convinced that art does not exist outside of the human

body, that it’s all so connected to the physicality of life. It’s not

just coincidence at all. Maelzel’s metronome points to moderato, which happens to be the human

heartbeat, and that “fast” and

“slow” are pretty much within

the range of the human heart. How high does a metronome go? A

metronome goes at about the speed your heart goes to when you’ve been jogging

for three miles. Maybe it is a little beyond that, or a little slower

than a healthy person’s heart would beat, but still, the musical range is

exactly the range of the human heartbeat, and the notion of slow and fast,

and crescendo of excitement is totally tied in with things physical.

The fact is that our range of hearing is within the range that human beings

can make vocally. When you think of a basso profundo range to a coloratura

soprano’s, this is about the range of an orchestra, extended a little bit

on both sides — piccolo and contrabass. But again,

everything is so related to us physically.

JD: I can’t think of any sorrows! [Laughs]

Maybe for the singers... I adore writing for the voice, and the more

I write the more I realize that everything is an imitation or glorification

of that. I’m so convinced that art does not exist outside of the human

body, that it’s all so connected to the physicality of life. It’s not

just coincidence at all. Maelzel’s metronome points to moderato, which happens to be the human

heartbeat, and that “fast” and

“slow” are pretty much within

the range of the human heart. How high does a metronome go? A

metronome goes at about the speed your heart goes to when you’ve been jogging

for three miles. Maybe it is a little beyond that, or a little slower

than a healthy person’s heart would beat, but still, the musical range is

exactly the range of the human heartbeat, and the notion of slow and fast,

and crescendo of excitement is totally tied in with things physical.

The fact is that our range of hearing is within the range that human beings

can make vocally. When you think of a basso profundo range to a coloratura

soprano’s, this is about the range of an orchestra, extended a little bit

on both sides — piccolo and contrabass. But again,

everything is so related to us physically. BD: Then how do we sift through all of this material?

BD: Then how do we sift through all of this material?| In the early morning hours of November

2, 2001, conductor Pierre Boulez was detained by Swiss security forces, whose

cross-check of hotel registries against a list of those known to have made

“terroristic” statements in the past turned up the name of a famous composer

and modernist musical intellectual. Evidently a malicious critic had once

phoned in a complaint to the Swiss authorities that Boulez had threatened

to “blow him up” after a bad review; the accusation went unchallenged, and,

correlated with a record of Boulez’s own incendiary comments about opera in

a 1967 interview with the German weekly Der Spiegel, formed enough of a pattern

to justify the temporary confiscation of his passport and some pointed questions

before he headed off to the airport. The interview had been published under

the provocative title “Blow Up the Opera Houses!” (Sprengt die Opernhaüser

in die Luft!) something which Boulez had indeed said, and though the Swiss

took a fair amount of ribbing for their literal-mindedness, the rhetorical

violence of Boulez’s rejection of the post-war operatic scene remains striking.

The call to blow up opera houses was in fact one of the milder moments of

the conversation, presented ironically as an “elegant, if costly” solution

to a proliferation of outmoded designs that prevented even the newest of German

concert halls from embracing technical advances in staging. No aspect of

post-war operatic culture escaped the revolutionary’s wrath: the opera world

was a self-segregating “ghetto” for intellectual suicides; the typical opera

house was a “musty closet,” a “music museum”; the one he knew best, in Paris,

was badly maintained, full of “dust and shit,” fit only for musical “tourists”

whose taste he found “sickening.” Boulez’s prescription for this sclerotic

opera culture was a therapeutic “bloodletting” along Maoist lines, complete

with imported cadres of Red Guards to crack heads. |

BD: You were looking at libretti?

BD: You were looking at libretti?|

Jacob Druckman, 67, Dies; A Composer and Teacher

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI Published: May 27, 1996 The New York Times [with corrected birth date; the published version stated June 25, but according to his son, Daniel, June 26 is correct.] Jacob Druckman, a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer, teacher and conductor who, through his work as a consultant to major symphony orchestras and a president of foundations, became an influential proponent of contemporary music, died on Friday at the Yale Health Service in New Haven. He was 67 and lived in Milford, Conn. The cause was lung cancer, said his wife, Muriel Topaz Druckman. Although he spent most of his career teaching at universities, most notably the Yale School of Music, there was little that could be called academic about Mr. Druckman's music. He was best known for his vividly scored and viscerally dramatic orchestral works. His professional approach to composition and his belief that young composers should be out in the field working with orchestras, writing large pieces for large audiences, had a major impact on his many students, several of whom, like Michael Torke, Aaron Jay Kernis and David Lang, have achieved significant success. As a young composer, Mr. Druckman studied and employed aspects of Serialism in his music, and his later works retained compositional rigor. But in the late 1960's he greatly diversified his musical language, becoming a skillful exponent of electronic music and incorporating elements of theater into his concert works, including narrative and ritualistic scenarios. But the exploration of timbre and instrumental color remained the hallmark of his style. Commenting on his 1979 work "Aureole," commissioned by Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic for a tour to the West Coast and Japan, Mr. Druckman wrote that whereas other composers considered orchestral color "decorative," for him it was an "intrinsic and structural" concern, "as central to me as sonata allegro form was for Mozart." The critic Peter G. Davis, writing of that work in The New York Times, termed it "virtually a textbook demonstration of how to achieve shimmering, vaporous, iridescent textures from a full symphony orchestra." Jacob Raphael Druckman was born in Philadelphia on June 26, 1928. As a youth he studied piano and violin and played trumpet in jazz ensembles. In 1949, he studied composition at the Berkshire Music Center with Aaron Copland, who remained an important mentor. That fall he entered the Juilliard School, where his teachers were Peter Mennin, Vincent Persichetti and Bernard Wagenaar. A Fulbright fellowship took him to Paris for study. After completing his master's degree at Juilliard in 1956, he began teaching there, an association that lasted until 1972, when he joined the faculty of Brooklyn College. In 1976, he was appointed chairman of the composition department at Yale, where he remained a professor of music until his death. Mr. Druckman's first large-scale orchestral work, "Windows," given its premiere by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1972, won that year's Pulitzer Prize in music. Reviewing the work, the New York Times critic Donal Henahan wrote of its "pulsating breathlessness." In one of his most important associations, Mr. Druckman was appointed composer in residence with the New York Philharmonic in 1982, also serving as artistic director of the Philharmonic's Three Horizons Festivals. The 1983 and 1984 festivals explored the "new romanticism." The concerts were provocative and well attended. Some composers associated with the cerebral so-called uptown school accused Mr. Druckman of pandering. But in his essay for the programs, Mr. Druckman argued that he was not advocating any movement, but simply noting a decisive shift in the "steady underlying rhythm of music" toward the "sensual, mysterious, ecstatic, transcending the explainable." The programs were striking for their inclusion of such diverse composers as Tōru Takemitsu, David Del Tredici, Luciano Berio, John Adams and Donald Martino. The most upsetting event of Mr. Druckman's professional life was the debacle of his Metropolitan Opera Commission. An opera based on the Medea story by Mr. Druckman was to have been part of the Metropolitan Opera's centennial celebrations. But this commission came in 1981, at the same time Mr. Druckman's association with the New York Philharmonic began. A slow worker, Mr. Druckman found the task of writing the opera more daunting than he had imagined. There were creative disputes over the libretto by Tony Harrison, a British poet. By 1986, the Met had canceled the commission. A production in Bonn was announced, but those plans fell through as well. In 1991, Mr. Druckman was appointed president of the Aaron Copland Fund for Music. In this position, his work was viewed as insightful and eminently fair. Just last month, although in bad health, he attended a meeting in New York. In addition to his wife, who was formerly head of the dance faculty at Juilliard and is currently a writer for Dance magazine, he is survived by a son, Daniel, a percussionist with the New York Philharmonic; a daughter, Karen Jeanneret, and three granddaughters. A memorial service will be held on Wednesday at 1 P.M. at the Robert E. Shure Funeral Home in New Haven. |

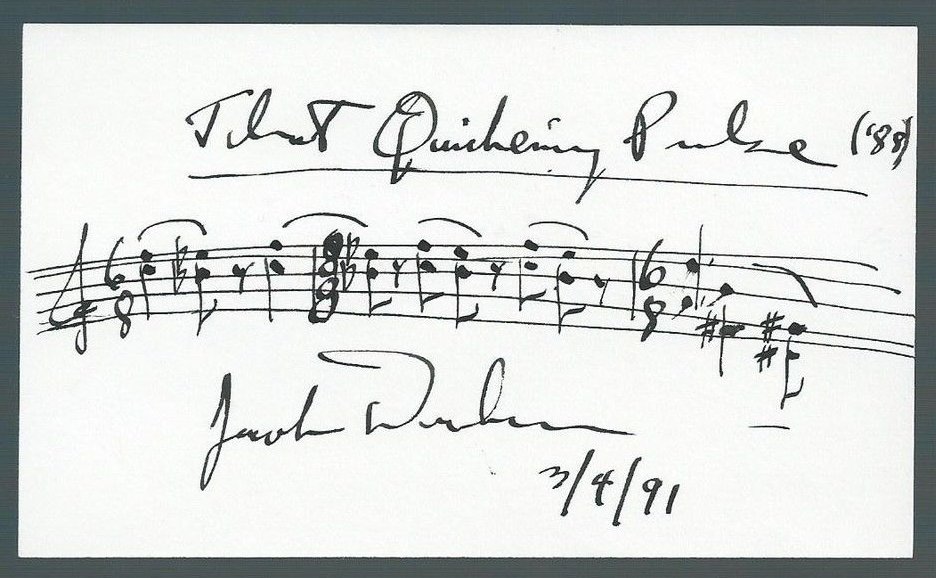

This interview was recorded in the office suite of the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra on March 22, 1989. Segments were used (with recordings) on

WNIB in 1993 and 1998. It was also used on WNUR in 2006 and in 2009,

and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio also in 2008. The transcription

was made and posted on this website in 2014.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.