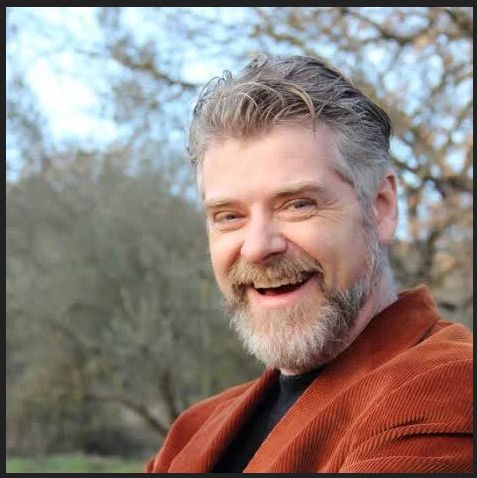

Baritone Roberto Scaltriti

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

In the fall of 1995, baritone Roberto Scaltriti appeared with Lyric

Opera of Chicago as Masetto in Don Giovanni. The cast included

James Morris in the

title role, Bryn Terfel and later Alan Held as Leporello, Luba Orgonasova

as Donna Anna, Carol Vaness

and later Juliana Rambaldi as Donna Elvira, Frank Lopardo as Don Ottavio,

Susanne Mentzer and

later Andrea Rost as Zerlina, and Carsten Stabell as the Commendatore.

Yakov Kreizberg

conducted, and Matthew Lata directed the Jean-Pierre Ponnelle production.

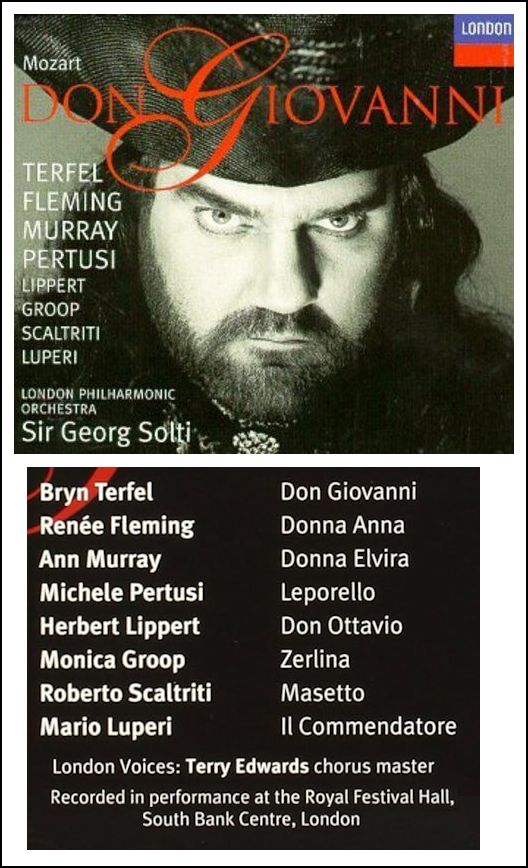

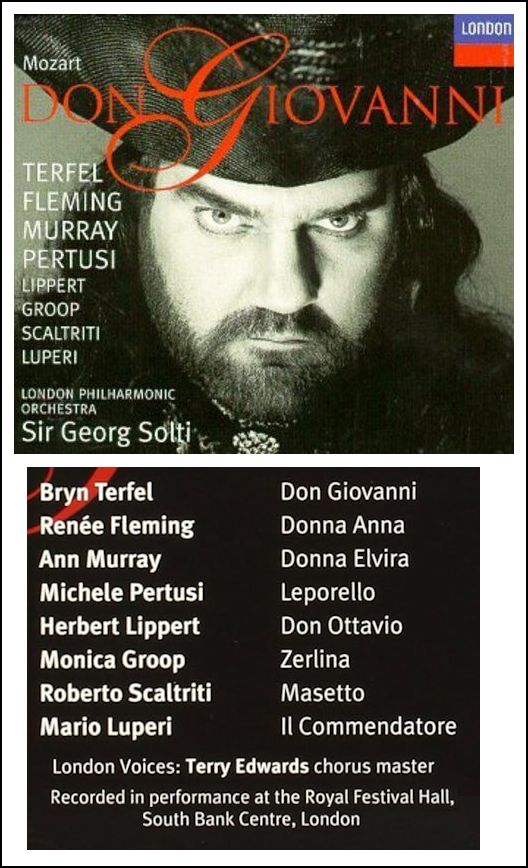

[Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interviews

with Renée Fleming,

Ann Murray, and Sir Georg Solti.] [Names

which are links on this webpage refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.]

Between the second and third (of twelve) performances, Scaltriti

was gracious enough to sit down with me for an interview. His

English was quite good, though at one point it did frustrate him a bit

not to be able to expound as he would have liked. However, his ideas

came across directly and understandably. Portions of the conversation

were aired on WNIB, Classical 97 to promote the later performances, and

again when his recordings were presented on the Sunday Evening Opera.

Now, thirty years later, I am pleased to present the entire encounter

on this webpage.

Since he was singing Mozart at that time, that is where we began

. . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Is there a secret to singing

Mozart?

Roberto Scaltriti: A secret? No...

he’s my favorite composer at the moment.

BD: Why?

Scaltriti: Because my voice suits it very

well. It’s what they told me, and what I feel personally,

and because it’s a good feeling I have for this sort of music. It’s

not just because of the singing, but also the theatrical part. The

Mozart operas are very interesting, and I really love to be in them.

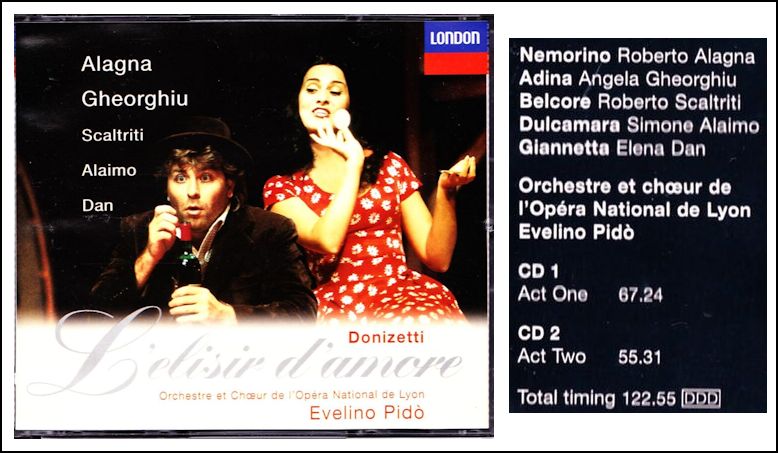

BD: You’ve also sung some bel canto

operas?

Scaltriti: Some, yes.

BD: Is there a big difference between the

Mozart style and the Italian bel canto style?

Scaltriti: It depends. I don’t think

there should be such a big difference. It’s more about the attitude.

In the bel canto you have mainly the singer coming and singing,

and, of course, caring a lot about putting the inflections into the music.

Then there is the line and the beauty of the sound. In Mozart,

especially in the baritone and bass roles, you can be a little bit more

comfortable, because there are other things which are of more concern...

such as the stage. Sometimes the words are more important than

the melodies, but this is just from my point of view. If you speak

to the soprano when she’s singing Donna Anna, or a tenor who is singing

Ottavio, they would probably tell you there is no difference at all,

because they have incredible lines to sing.

BD: For you, does the balance between the

music and the words change from opera to opera?

Scaltriti: There are operas where I feel

the libretto is not as interesting as the words, and they are just written

for making sound. This is basically Rossini, for example.

In his operas, all the talking is done very quickly, and is basically

on the music. In Mozart we must be very comfortable and confident

about the meaning of the text, because it has a beautiful libretto which

is so full of double-meanings. So it depends really on what the

director wants, but you can make an interesting job of it.

BD: The double-meanings of the words would

be Da Ponte, but Mozart underlines them. Do you have to underline

them as well?

Scaltriti: Yes... well, this I don’t know.

It really depends on the conductor. It’s not often so much a

choice of the singer, but Da Ponte and Mozart worked so well together.

It seems to me that every time Da Ponte wants to put in double-meanings,

Mozart agrees in the music, and it’s very, very interesting. It’s

one of the better collaborations between the composer and the librettist.

BD: Here in Chicago you’re singing Masetto,

but you’ve also sung the title role of Don Giovanni.

Scaltriti: Yes.

BD: When you’re involved in a production

as Masetto, do you pay particular attention to the man singing Don Giovanni,

so that you can pick up tricks for when you sing that role?

Scaltriti: Of course I do, but it depends...

In some cases I have sung Masetto and understudied Giovanni,

so I did pay a lot of attention to it. This time I’m just enjoying

listening, but I’m more focused on Masetto, and really just taking care

of that.

BD: Can you really do a lot to bring Masetto

to life?

Scaltriti: It depends on whether the production

is open to new ideas, or if it is a revival, like in this case. As

much as possible, here in Chicago we have tended to redo it exactly

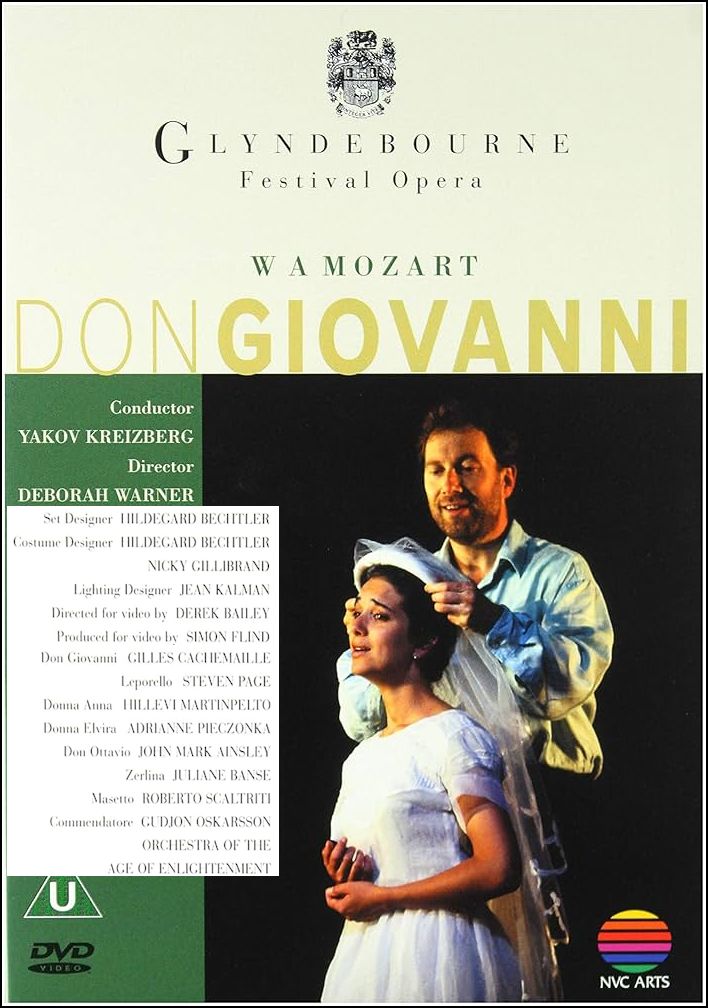

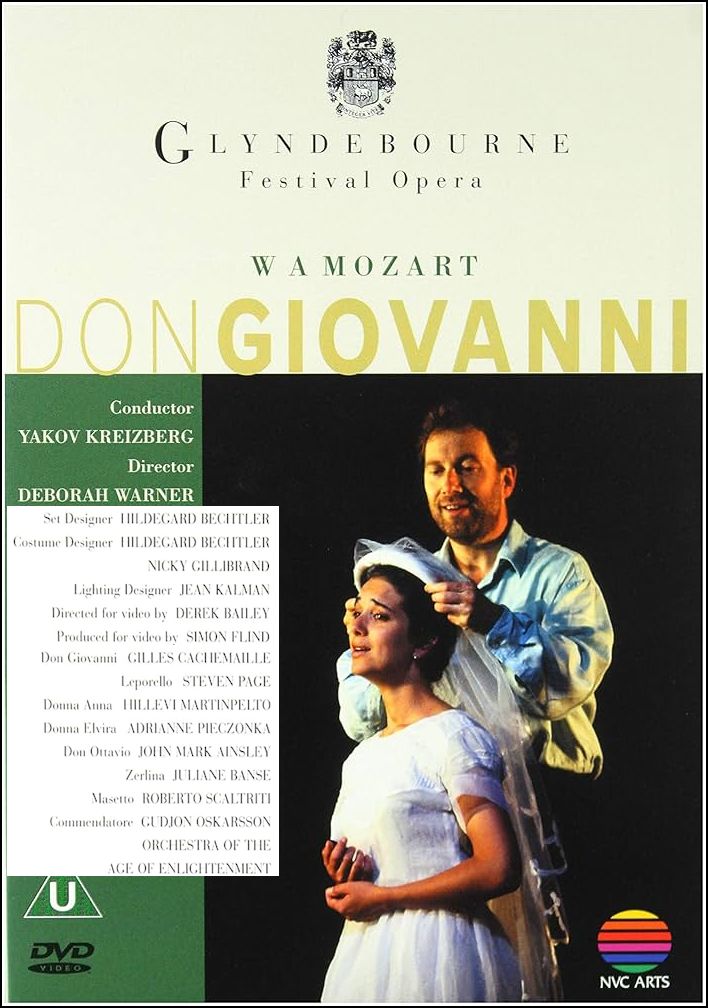

as it was. I had one experience in Glyndebourne where we created

every character. This was the production by Deborah Warner, and

it was a very modern production. It was really a change from any

vision of the opera, because we were wearing normal clothes, and had almost

no make-up. The set was also very modern.

BD: The cast was in everyday street

clothes?

Scaltriti: Yes, and we were supposed

to play the action in 1994. So it was very different. But

what was good was that everybody was given the freedom just to create

one’s own role, and to allow one’s own personality a bit into the roles.

So Masetto was more of a very temperamental boy than a simple peasant,

as it should be played all the time. In a way it was interesting,

but it was very, very different from every other Masetto I could imagine

or have seen. Personally, I like it very much when Masetto is like

he is here, a young peasant who has a relationship with Zerlina. It

was pretty dramatic playing Masetto in 1994. It showed the problems

of the couple not really getting along very well! It was an actual

problem in fact!

BD: Can you bring some of the ideas from

1994 into the general character of Masetto, or in the general character

of Don Giovanni?

Scaltriti: That’s more difficult.

Maybe Don Giovanni... [Both laugh]

BD: Are there Don Giovannis living today?

Scaltriti: [Thinks a moment] Yes, a little

bit! Of course, the problem of playing Don Giovanni in 1994

is how can one really play the nobleman with everything concerning that

rank? He has power, and the fact is that everywhere he is arriving

he is welcome.

BD: [With a wink] Here in the United

States, the advertising says that if you have an American Express Gold

Card, you are welcomed everywhere! [Both laugh]

Scaltriti: Yes, but there is something else.

I’m reading at the moment The Memoirs of Casanova, which

adds a little bit of collaboration with Da Ponte and the libretto of

Don Giovanni. I find it extremely interesting, not for the

list of the women he actually had

— because it’s a never-ending

list! —

but it’s the costumes and the style of the time. Wherever

he was arriving he had a personal moment in his life. This is not

just because he was so rich. He was also very poor sometimes, but

the fact that he was a noble in his attitude. That makes somebody

welcome everywhere. I don’t really think we can imagine something

like that today, even for a person with money. It’s something

very special.

BD: It really is the attitude?

Scaltriti: Yes, yes.

BD: Aren’t there people today who have that

bearing, and that attitude?

Scaltriti: There are, but the society has changed.

That’s what I mean. What I am talking about is when Casanova

was arriving in a hotel, for example, in this hotel there were other

families who were probably socially less powerful. They really tended

to try to have his attention, and felt it necessary just to spend some

time with him.

BD: Were they intimidated by him?

Scaltriti: Probably, as well, but they were

more fascinated than intimidated by him.

BD: I wonder if there’s a parallel, perhaps,

between that scenario and the great big movie stars today, or maybe The

Three Tenors. Would they get that kind of attention?

Scaltriti: It’s different because they are

really popular. That is really something which is fascinating to

the people. In the case of Casanova, it’s difficult to explain...

[Here he briefly laments not being able to fully convey his thoughts

in English.]

* * *

* *

BD: When you’re portraying these characters

on the stage, is it more difficult for you because you’re playing to

an audience of 1995, as opposed to the audience of 1789?

Scaltriti: [Laughs] That’s a good question!

I’m just trying to make a parallel between the two

things. Of course I’m fascinated about that period, and all of what

I have seen and read about it. The film Amadeus by Miloš

Forman, for example, was something sensational, and that I really enjoyed.

Other films of that century, such as Dangerous Liaisons, or the

same story also by Miloš Forman, Valmont, were really giving me

an idea of what could be. On stage we play something about the style,

and about our ideas, and what we all know. But it’s also supposed

to be appreciated by the audience. So, I’m not really sure what

I’m really doing in this case! [Laughs]

BD: You’ve played these roles in Glyndebourne,

which is a very small theater, and now you’re playing one here in Chicago,

which is a very large theater. Do you change your vocal technique

at all for the size of the house?

Scaltriti: I must admit, not really.

My surprise, and actually my pleasure, was to go first when I arrived

to listen to Don Pasquale in the auditorium. The acoustic

was great, really beautiful, and I didn’t have any trouble hearing any

of the singers [Paul Plishka,

Ruth Ann Swensen, Bruce

Ford, and Timothy Nolen,

conducted by Paolo Olmi.

Paolo Montarsolo

(himself a famous Pasquale in years past) directed the John Conklin production.].

I thought that the beauty of the sound was really extremely good, even

better than in a small theater where I’ve been singing. So I

was not intimidated when I started to sing. Also, because everybody

who was in the auditorium

— the coach, and the other musicians who

are collaborating with us

— were giving us adjustments about the

balance. Of course, if they say that it sounds all right, we do not

need to push. Pushing is not a good thing, and it doesn’t mean you

can be heard any more than without pushing. It’s just psychological.

If the sound is enough, it’s enough, and there’s

not much you can do about it.

BD: You know that your sound will fill the whole

house?

Scaltriti: I don’t have this feeling

myself on stage. I’m not really feeling it, but there is no

advantage in trying to push in order to feel things are then going

to be better. Most of the time if you push the sound, then it’s

not so good. You rely on what they tell you! [Both laugh]

BD: You go with what they tell you,

and that feels good for the voice?

Scaltriti: Yes.

BD: You’ve made a couple of recordings.

Do you change your technique at all for the microphone?

Scaltriti: In depends on what I hear when

I go to listen to the master recording. If I feel that there

is something I can improve, of course I change it, but not really so

much. I must admit the pre-action of the voice for a recording

and for a theater is different. There is something that they

know very well when they are making a recording, and that is the distance

that every singer should have from the microphone. Some singers

are closer, and some singers are further away, and that’s already a

good way for setting up everything.

BD: Where do you stand? Are you closer

to the microphone or further away?

Scaltriti: I am pretty far away from the

microphones.

BD: That’s a good indication of what they

expect!

Scaltriti: [Smiles] Well, it depends!

I really don’t know. It’s just that probably my voice focuses

better a little further away, but it doesn’t really mean necessarily

that it is a good sign.

BD: Are you pleased with the records that

have come out so far?

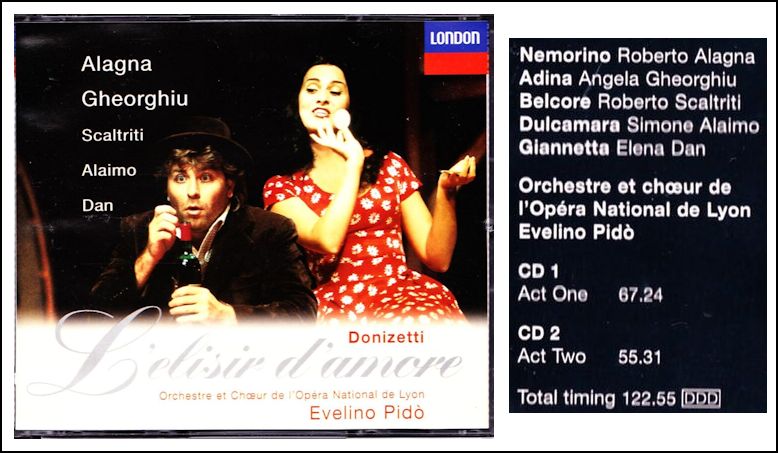

Scaltriti: Up until now they are tiny roles

because I have had little experience with Verdi’s operas. The recordings

include Rigoletto [Marullo, with Nucci, Pavarotti, Anderson, Ghiaurov, Verrett, De Palma; Chailly], Il Trovatore

[An Old Gypsy, with Pavarotti, Banaudi, Nucci, Verrett, De Palma; Mehta], Un Ballo in

Maschera [Silvano, with Crider, Leech, Chernov, Bayo, Zaremba,

Howell; Rizzi] and Traviata

[Baron Duphol, with Te Kanawa,

Kraus, Hvorostovsky, Borodina;

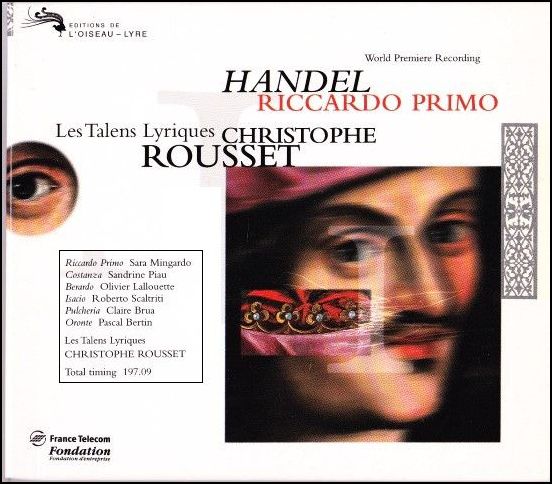

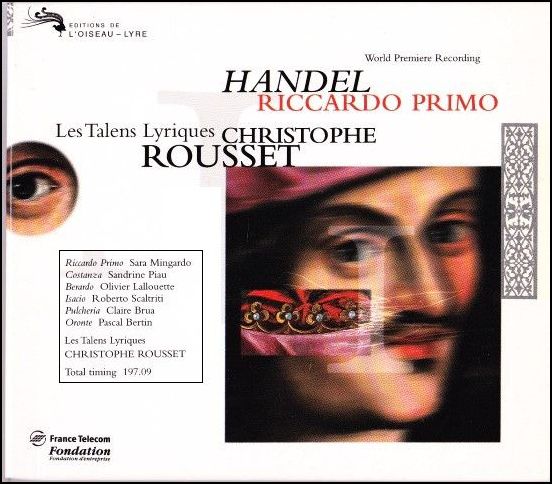

Mehta]. However, we recorded a Handel opera in the summer, but

it’s not out yet. [Photo is shown below-left] I’m

very curious to listen to it.

BD: Is that a bigger part?

Scaltriti: Yes, that one’s pretty big.

It’s the role of Isacio [the Governor of Cyprus] in Handel’s Riccardo

Primo [Richard I, King of England]. We recorded it in Fontevraud

Abbey in France, which is the place where Richard the Lionheart is

buried. We did this opera in concert there, and then we recorded

it. The music is beautiful, with the chorus and an orchestra of

original instruments, so that the pitch was A=415, not 440, which is as

it should be for Baroque works. Personally, I was very pleased.

It is really beautiful music.

BD: We have talked quite a bit about Mozart.

Is there a difference between singing Mozart and singing Handel?

Scaltriti: I’m not an expert. I’m not somebody

who really knows about style, but my future wife is a musician, teaching

at the Conservatoire de Paris, and she is really into Baroque music.

So she told me about it, and we worked a lot on the cadenzas and

appoggiaturas, and all of what you need to make that music into

a good style. If you play bel canto, you are not really used

to making this sort of ornamentation, which is not so much in Handel.

Earlier music is much more complicated, such as the French Baroque music.

It’s really an enormous task. I found it very comfortable singing

Handel. It is extremely vocal, and very well written, especially for

my sort of voice. I must be careful not to allow my vibrato to be

too much, because the size of the orchestra is not so big, and it can sound

a little bit weird if you sing it like it could be Verdi. [Both laugh]

BD: If you put a Baroque orchestra under

Verdi, you’d completely swamp it!

Scaltriti: Yes! [More laughter]

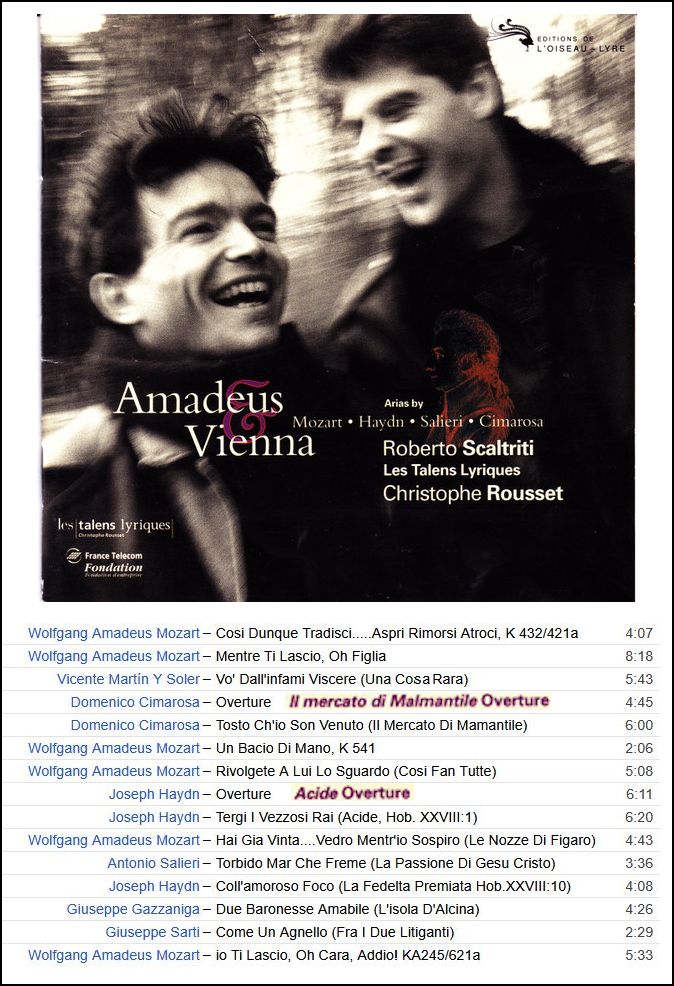

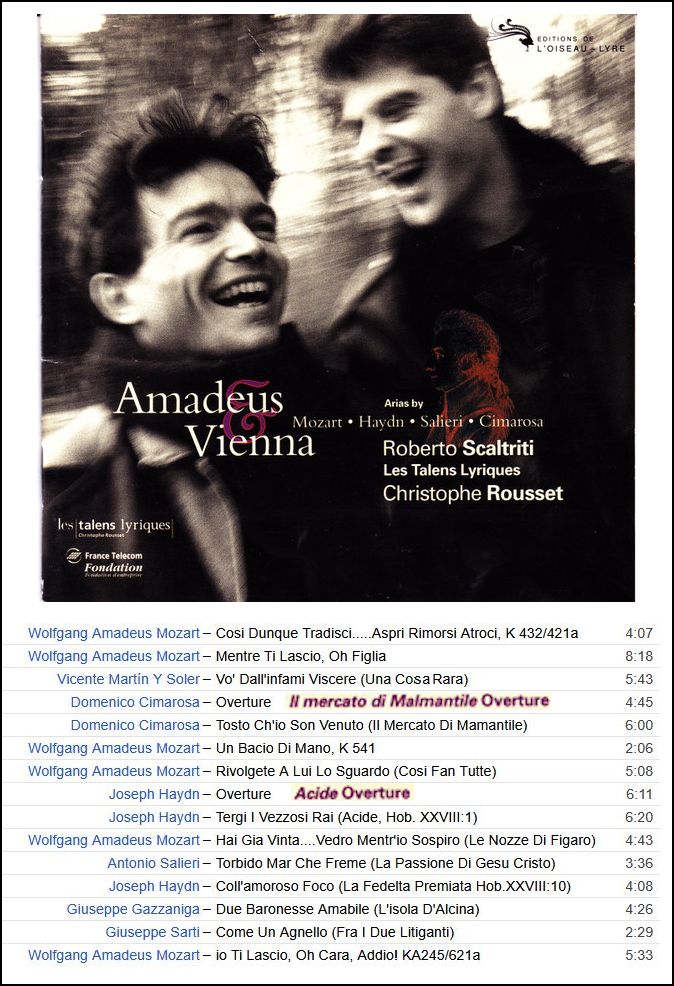

BD: I understand you have a Mozart concert aria

recital. Has it been recorded yet? [This recording is shown

above-left]

Scaltriti: No, that has not yet been done.

It’s an idea coming from Christophe Rousset, who was the conductor

in this Riccardo Primo that we did in France. The idea at

the beginning was to sing the Mozart concert arias for bass-baritone.

Then we realized there are not so many, and so we thought about

putting together other composers who were active in Vienna at the time

when Mozart and Da Ponte were working together. We thought about

Giuseppe Gazzaniga, or Vicente Martín y Soler, or Antonio Salieri,

and a little bit of Haydn. What was very interesting for us at

the beginning were the two other operas which are quoted in Don Giovanni,

namely Una Cosa Rara by Soler, and I Due Litiganti by Sarti.

Bits of these are played in the supper scene [along with a bit of Mozart’s

own Marriage of Figaro]. Una Cosa Rara is the finale

of Act 1, so it’s an ensemble, and can be sung as an aria, but the bit

of I Due Litiganti is an aria written for a buffo. It’s

in a key for an old tenor, but we have found the manuscript in Paris

which has the bass line down one tone lower. So this could mean that

the buffo aria was sometimes sung by a baritone, or sometimes by a tenor.

Of course, we are not sure about it, but in my case [laughs] we sing it

in the baritone key.

BD: At least the fact that you’re not sure

means there could be some flexibility.

Scaltriti: Yes!

BD: There’s always the little bit of rewriting

and retouching in the early operas.

Scaltriti: Yes, absolutely.

BD: Do you think there should be rewriting

and retouching for the newer operas, too?

Scaltriti: I don’t know about this. Of

course, the manuscripts of operas which are nearer to our time are something

that we are more sure about. The autographs are not manuscripts,

as, for example, The Coronation of Poppea, where you have bits

written for Venice, and bits for Naples, and sometimes an aria is not written

in the one or the other, so now they just fill it up as best as possible.

But about Falstaff, there is not so much to be worried about, I

suppose! [Both laugh]

* * *

* *

BD: Are you a bass, or a baritone, or a bass-baritone?

What is your category?

Scaltriti: I started as a bass, but I started very,

very young. I was only seventeen years old at the time of my first

work. It was in Philadelphia, with the Philadelphia opera company,

which was part of their annual International Voice Competition. Since

then I have continued. I had just started my studies at the conservatory,

and I did my training in the conservatory at the same time I was singing

small roles around Italy and in Europe from time to time. My voice

is developing more and more as a baritone than as a bass, but for the

moment I’m sitting on repertoire which is recognized as being sung by both.

In a few years’ time I will see if I will be interested in the bel

canto more than what I am doing at the moment, and really then I

will try to choose which voice is mine.

BD: You’ll probably be a Zwischenfach

[between two categories; one who chooses from both lists] for your

whole career!

Scaltriti: [Smiles] I don’t know...

It could be nice, but it could be very dangerous, so I try to be very

careful.

BD: When you’re offered a role, how do you

decide yes or no?

Scaltriti: It depends on the way it is written.

First of all, if it is very dramatic, I tend to say no right from the

start. It depends on the volume of the orchestra, which is accompanying

the bits you are singing, and then also on the style. For example,

Handel can be very, very high, especially at the A=440 pitch. But

as you really play it with a lot of coloratura, you can touch very high notes

with a very specific technique which is not damaging to the voice at all.

But if we’re talking about Puccini, or even more dramatic repertoire,

you need to go up to those notes with a completely other technique. That’s

especially true for a young singer, and it’s very, very dangerous... at least

it is for me. [Both laugh]

BD: So you have to be very careful?

Scaltriti: Yes, sure. I’m not even

thinking about it at the moment.

BD: Are you pacing yourself with the number

of performances you give each year?

Scaltriti: No, I don’t really think about the number

of performances. I’ve never counted how many I’m doing in a

year, but generally I’m taking opera productions with long rehearsals

periods. This means I’m not doing more than sixty or seventy

performances in a year.

BD: That gives you enough so that you

have a good income, and yet you get enough rest to keep the voice in shape.

Scaltriti: Yes, yes. Also, it’s good

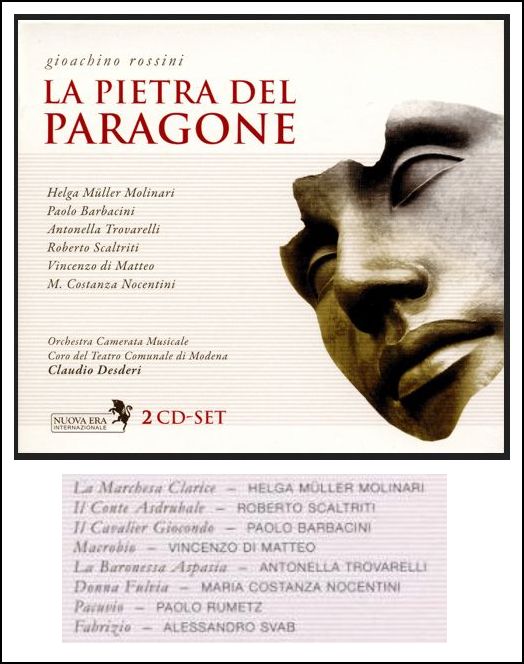

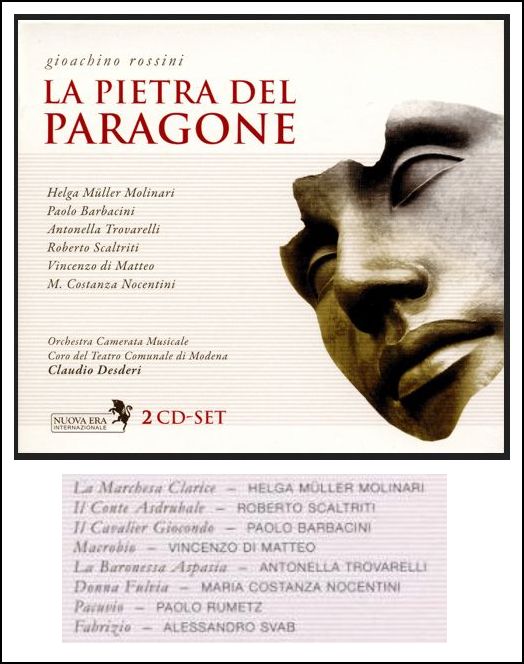

when I have some time off for learning new roles. I’m still studying

with Claudio Desderi

from time to time, so I go practicing with him. [Note that Desderi

is the conductor of the opera shown at right!] Another person

I really care about is Julia Hamary, who is teaching me in Stuttgart. She’s

a wonderful teacher as well. I’ve done a few masterclasses with

her. She is a really fantastic person.

BD: I assume you’re booked a couple of years

ahead?

Scaltriti: Yes.

BD: Do you like the security of knowing

that on a certain specific day a couple of years from now, you’re

going to be singing a certain role in a certain place?

Scaltriti: Yes, absolutely. That’s something

which is making life easier in a way, and it’s also nice to know that

you are booked for the good repertoire. I like to experiment with

new things, and to try out new roles, but not so much. In case

they are really difficult, I plan to have some time off before to really

practice them.

BD: You’re singing a couple of new roles

each year, but is it nice to come back to the old familiar roles?

Scaltriti: Sometimes. For example, I must

admit this year in the summer I was Masetto, and I was understudying Giovanni,

but it never happened. Before, I was understudying Giovanni in

1991 and 1994, and I just did the cover show and all the rehearsals,

but I never had the chance to go on for the regular performances.

This year instead, I went on for the dress rehearsal, and for the second

performance. I hadn’t sung Giovanni since 1990, and it was really,

really nice to refine it. Everything was like I had just left it

one month before. It was not a shock, so in a way it was easier than

other experiences with different music. It was very nice.

BD: Do you do any new operas, twentieth

century pieces, or contemporary works?

Scaltriti: I did a Menotti work, The

Telephone in Naples. This was June of 1995, but contemporary

music, no. I must admit I don’t do any at the moment. I have

not been offered any. I have absolutely nothing against it. It

could be interesting in the future, but at the moment I don’t sing any.

BD: You’ve also done Il maestro di cappella

by Cimarosa. How do you like being the whole show?

Scaltriti: That was very interesting. In

the beginning I was very surprised at this offer from the theater of

Florence. I was not going to accept it, because I felt that generally

it’s played by a very experienced singer. For example, Claudio Desderi

is a wonderful maestro di cappella, but he has many years of experience on

stage. But they insisted, and the idea was to have really a young

maestro di cappella, and to change completely the atmosphere on stage.

So I accepted with pleasure, and it was really great in the end.

We had a nice relationship with all the instrumentalists on stage, and

the idea of the producer was to make it like a proper orchestra feeling

as the atmosphere. The production was by Fabio Sparvoli, and we

really enjoyed the time doing it. It was weird, especially in the

beginning. We had about ten days without the orchestra, so I was completely

alone on the stage, pretending to speak with violins and double basses.

Once the orchestra was there, it was much easier and we could create

a feeling.

BD: Is that something you would look forward to

doing again?

Scaltriti: This production could be nice.

I don’t think really I could do it in another situation. I’ve seen

Claudio Desderi performing it in a production by Roberto De Simone.

That was really in the period, with wigs and costumes of the eighteenth

century. It was beautiful, but I rarely think you need to have

as young a singer as me.

BD: Come back to it in thirty years!

Scaltriti: A good idea, yes! [Much

laughter]

BD: Are you looking to have a long career?

Scaltriti: I’m actually looking to enjoy whatever

I am singing. I’m not really dreaming about big careers, or success,

or being booked the whole time. I really like to enjoy the operas

that I am already doing that now, and possibly changing the subjects

from time to time. I really like to go from one production to another,

where you change completely the way of playing a character. At the

same time, it is really fascinating for me to try to play as much as possible

as an actor. I’m not an actor. I did not do any schooling on

that, and when you find a good producer it’s a challenge. We can

really try to correct our movements. It’s a really good part of this

job, and I like it. What I hope is to go further, to improve more

and more my stage work, and also to try different styles. For example,

Don Giovanni in Glyndebourne was with an orchestra and original instruments,

so it was at a different pitch. It was a different style, and we

worked pretty hard the first year with Simon Rattle creating a style for

this opera. It was very different from singing with the orchestra

here, which is a larger symphony orchestra, of course. It gives

another idea, and you sing in another way. There are slight differences,

but they are not so big.

BD: How is it different?

Scaltriti: It is in the way you sing, and the way

you receive the sound of the orchestra, and the way you use your voice.

BD: It seems like a lot of it is a psychological

difference.

Scaltriti: Yes, of course.

* * *

* *

BD: Do you have any advice for younger singers coming

along?

Scaltriti: I have met many young singers recently,

and thought that many of them were really wonderful. Regarding the

Italians, many of them are already pretty famous. For example,

I started with Cecilia Bartoli when we were in Rome, but it’s not even

the case to speak about this great mezzo. She’s deserved a great

career, and I’m really happy for her. In Glyndebourne I had the

pleasure to work with Juliane Banse, who was Zerlina with me. She is

a very nice soprano, and in addition to the Mozart repertoire, I have

heard a wonderful record she has done with her teacher, Brigitte Fassbaender,

of duets by Brahms. She will have a very interesting career.

It’s a very beautiful voice.

BD: [At this point we stopped for a moment,

and he recorded a station break. I then asked his birthdate, which

he told me was April 6, 1969, so he was 26.] Are you at the point

in your career that you want to be at this still young age?

Scaltriti: I think so, definitely. What I

wanted at the beginning was not to burn the time very, very quickly.

Since the beginning, I was offered more important things than I have done

in some cases. I can very easily say no to many offers, and especially

today, having started with part of the Baroque repertoire, especially

Handel, but also Bach, I hope to sing more of those in my future.

I feel I can comfortably continue in this way for about ten years, and then

watch later to see what is going on. This is really a nice kind

of training I find for myself, to improve not just vocally but also psychologically

speaking. After all, it’s a job you enjoy more when you are more

mature, and you can deal better with the tension, especially for big theaters.

BD: Is singing fun?

Scaltriti: It can be! It can be not so fun

sometimes, especially if the situation of the production is not comfortable,

or if there are heated discussions between conductor and producer.

Then it can be hard. In Italy it can be very hard sometimes, because

productions are done quickly in a short space of time. Even at

the dress rehearsal there is a lot to do still. That makes life not

so easy, and it’s also why I intend to work abroad mainly.

BD: Are the Italian audiences the same or different

from the American audiences?

Scaltriti: I find the American audiences very enthusiastic.

They really enjoy our performances a lot. This is also probably

a matter of supertitles, that make opera more accessible. But

it should be done also in Italy. We’re supposed to understand perfectly

what is going on, but if you are singing, your diction is sometimes not

so clear. This also supposes a public which is very well educated,

and who knows their operas by heart. Sometimes they are just enjoying

the music, but they don’t really understand what the protagonists

are taking about.

BD: [With mock horror] You mean, the

text is important???

Scaltriti: [Laughs] I think it’s very

important! It depends which repertoire of course, but I think

it’s very important.

BD: Thank you for coming to Chicago, and for having

this chat with me.

Scaltriti: Thank you.

[This performance was also issued on video]

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 1, 1995.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following month, and again

in 1996 and 1997.

This transcription was made

in 2025, and posted on this website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this

website, click here.

To read my thoughts

on editing these interviews for print,

as well as a few other interesting observations,

click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until

its final moment as a classical

station in February of 2001.

His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since

1980, and he now continues his broadcast

series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited

to visit his website for

more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews,

plus a full

list of his guests.

He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in

the automotive field more than a century

ago. You may

also send him E-Mail

with comments,

questions and suggestions.