|

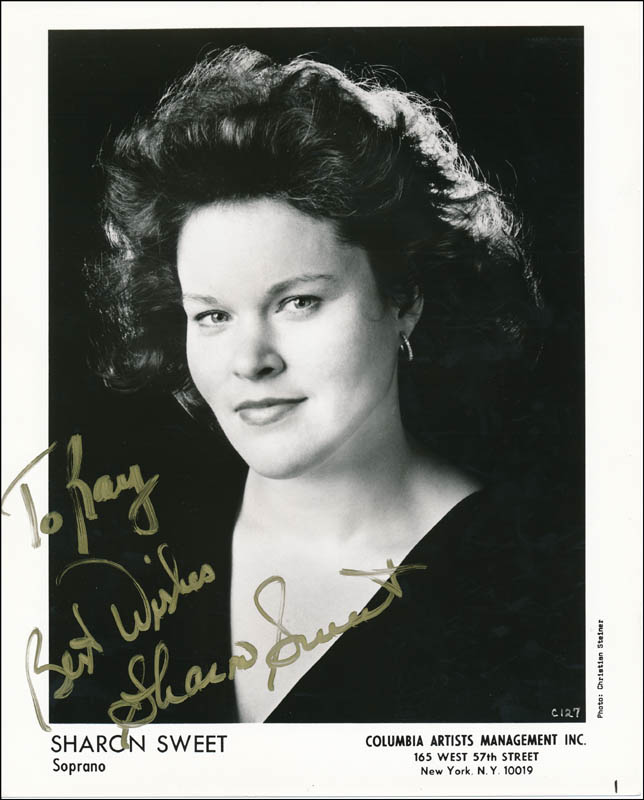

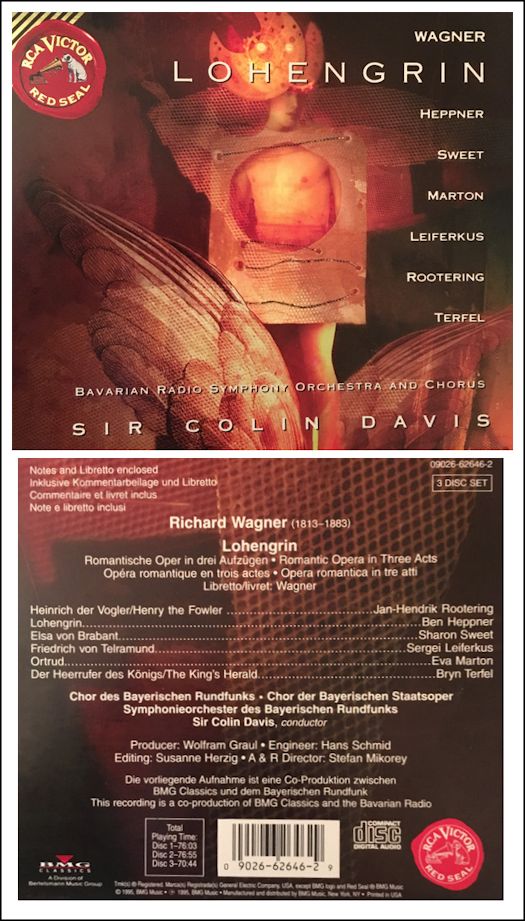

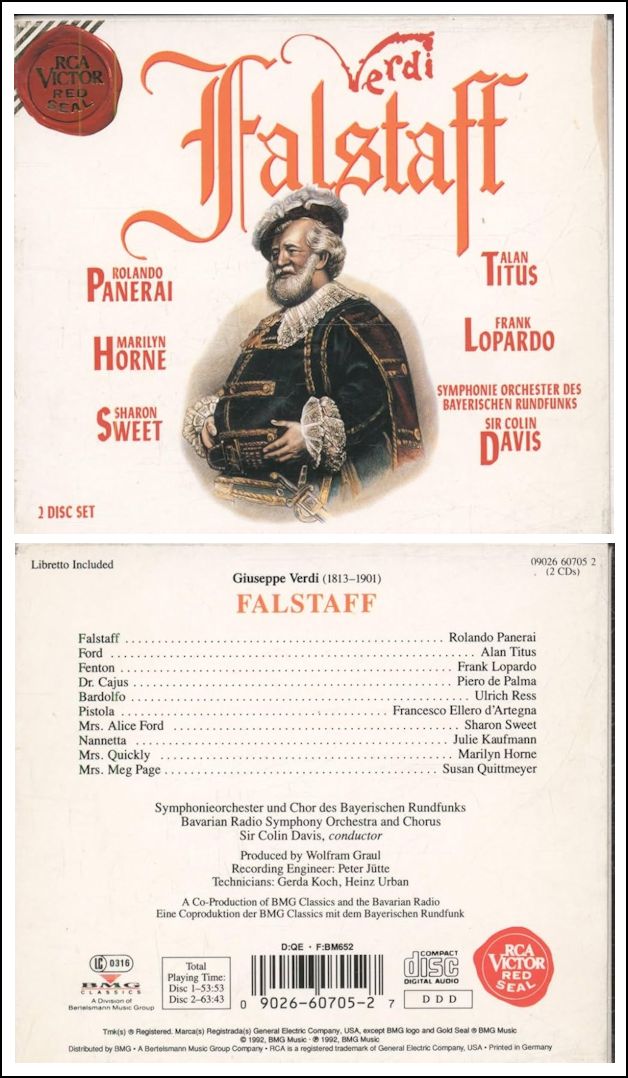

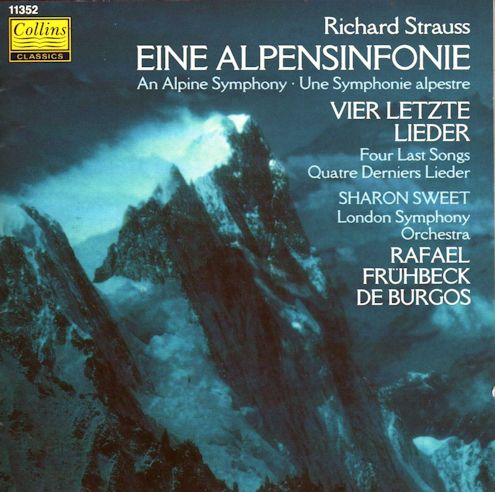

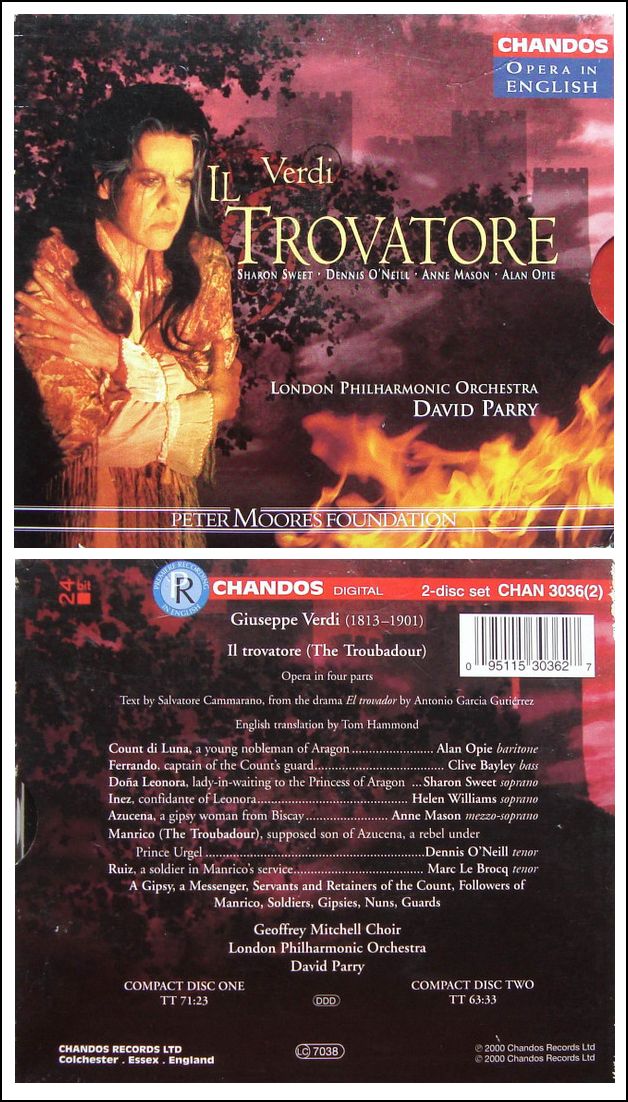

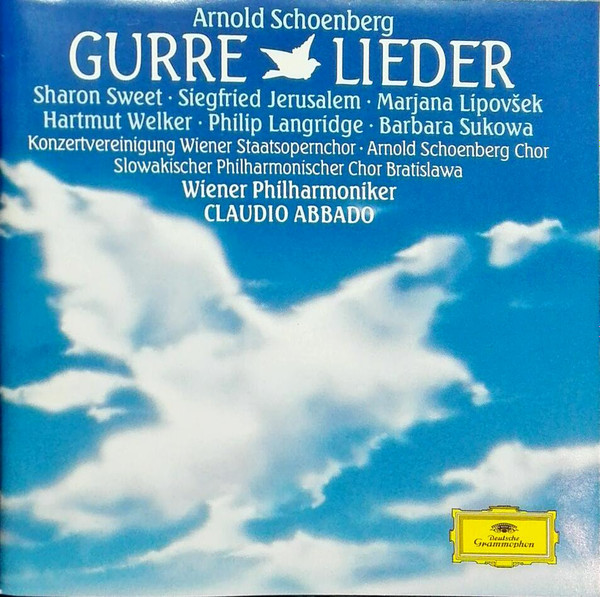

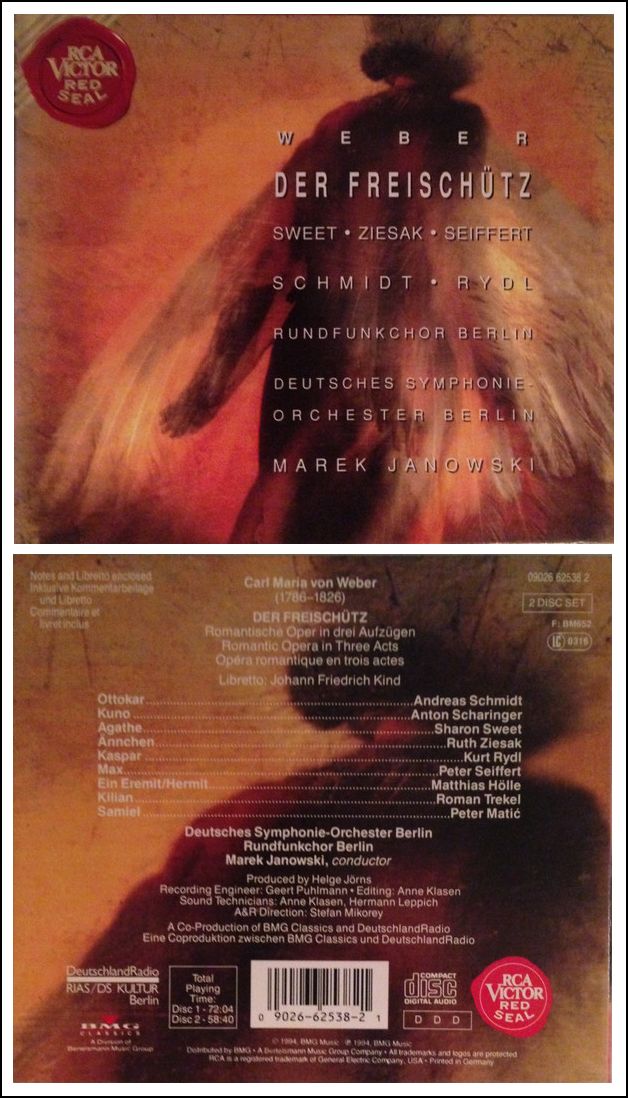

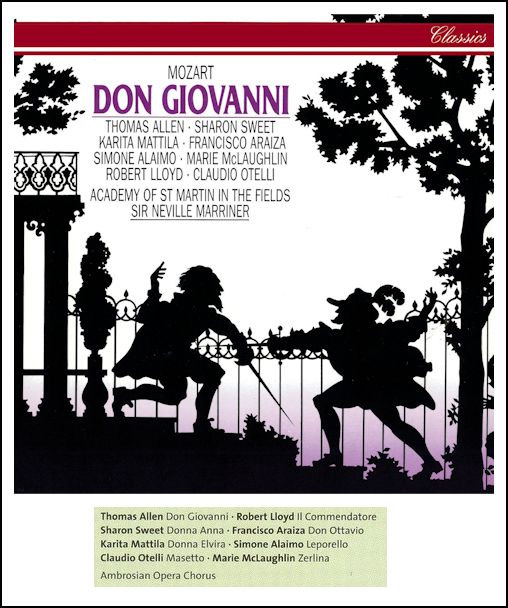

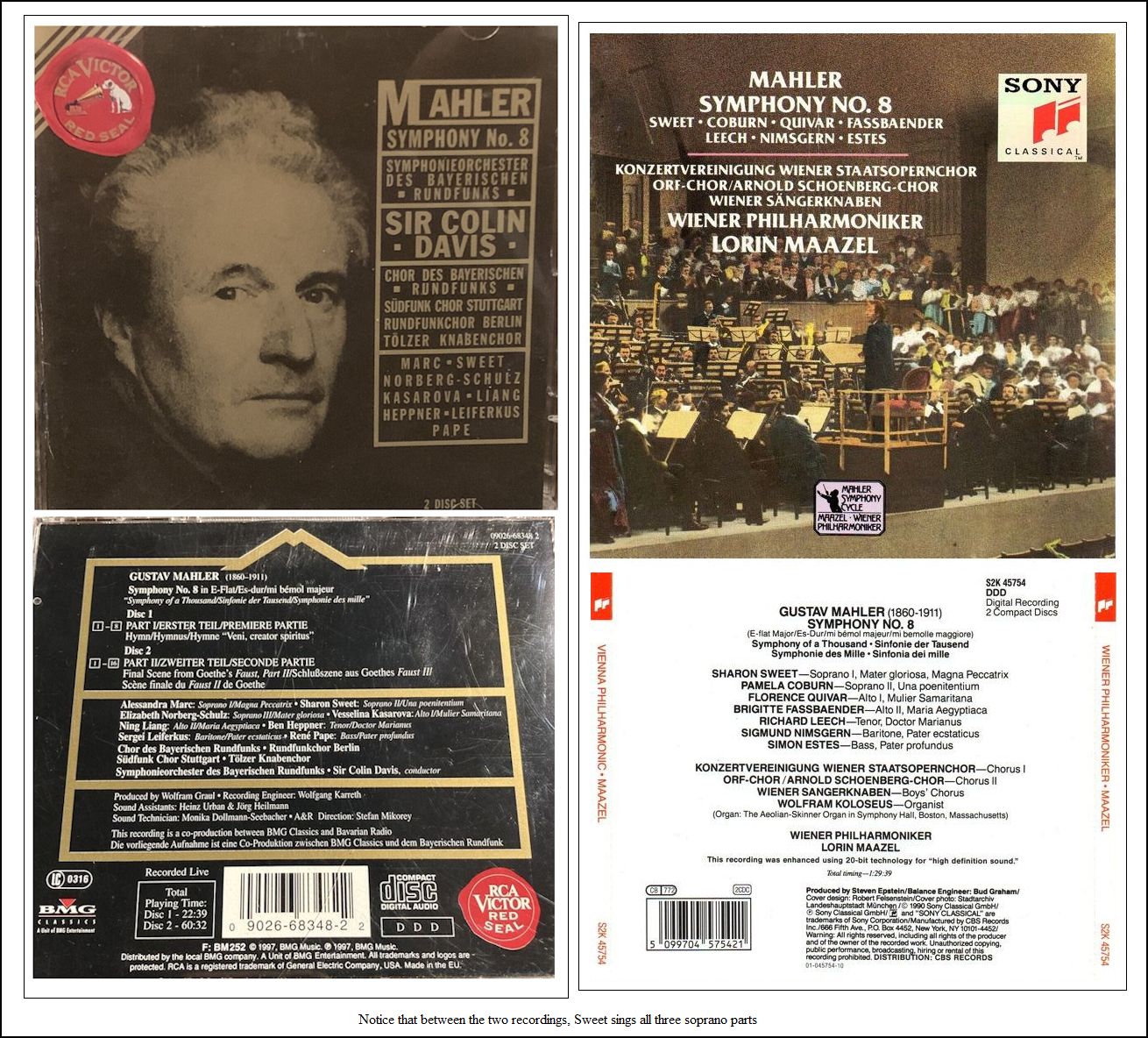

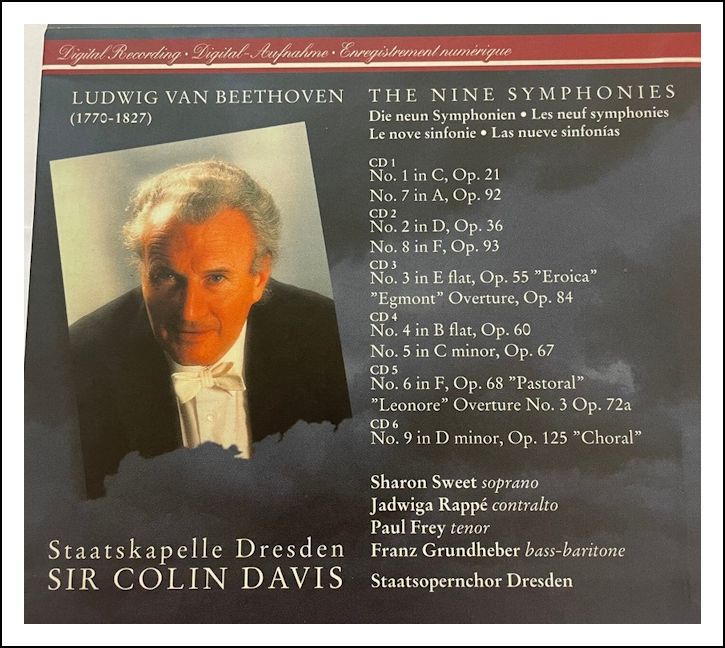

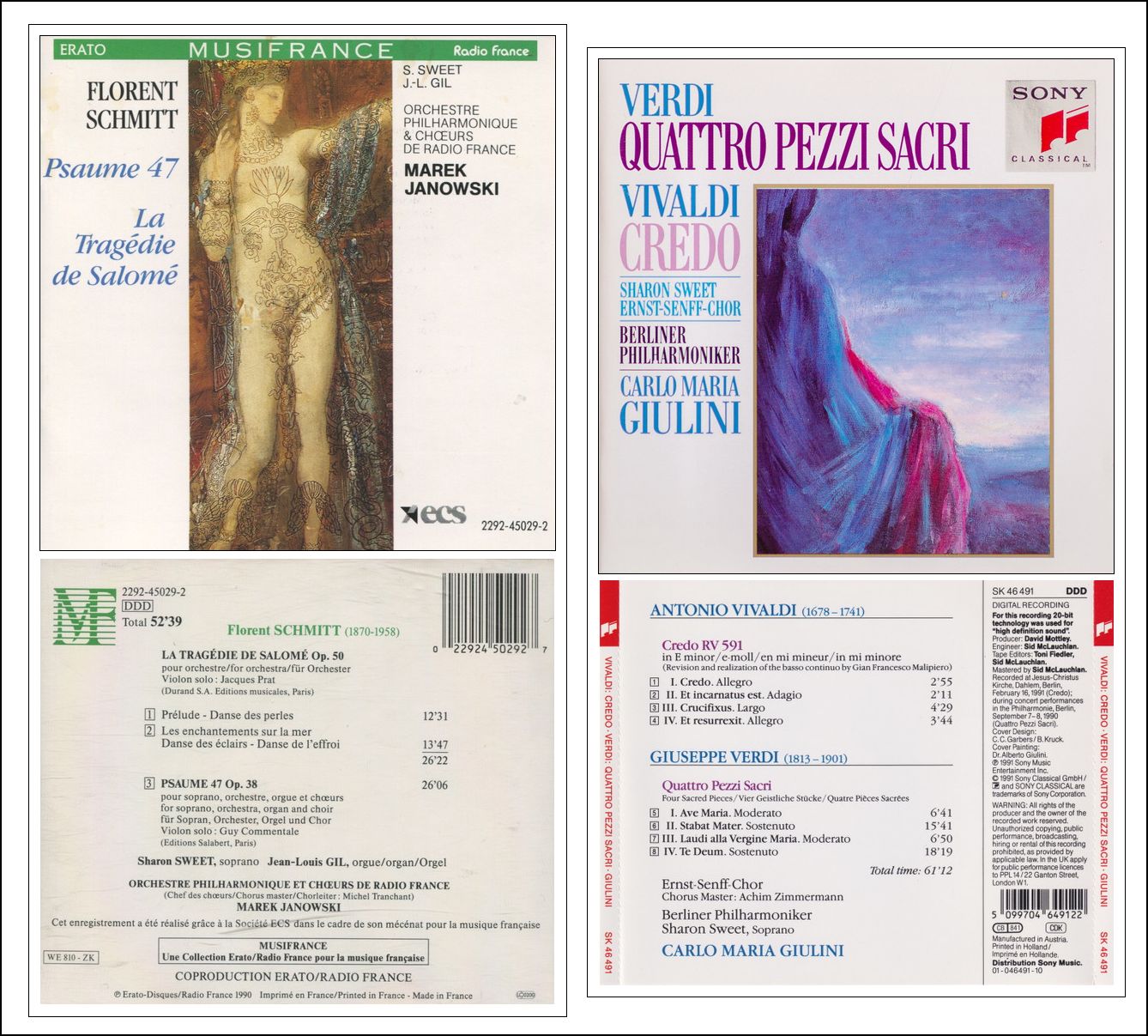

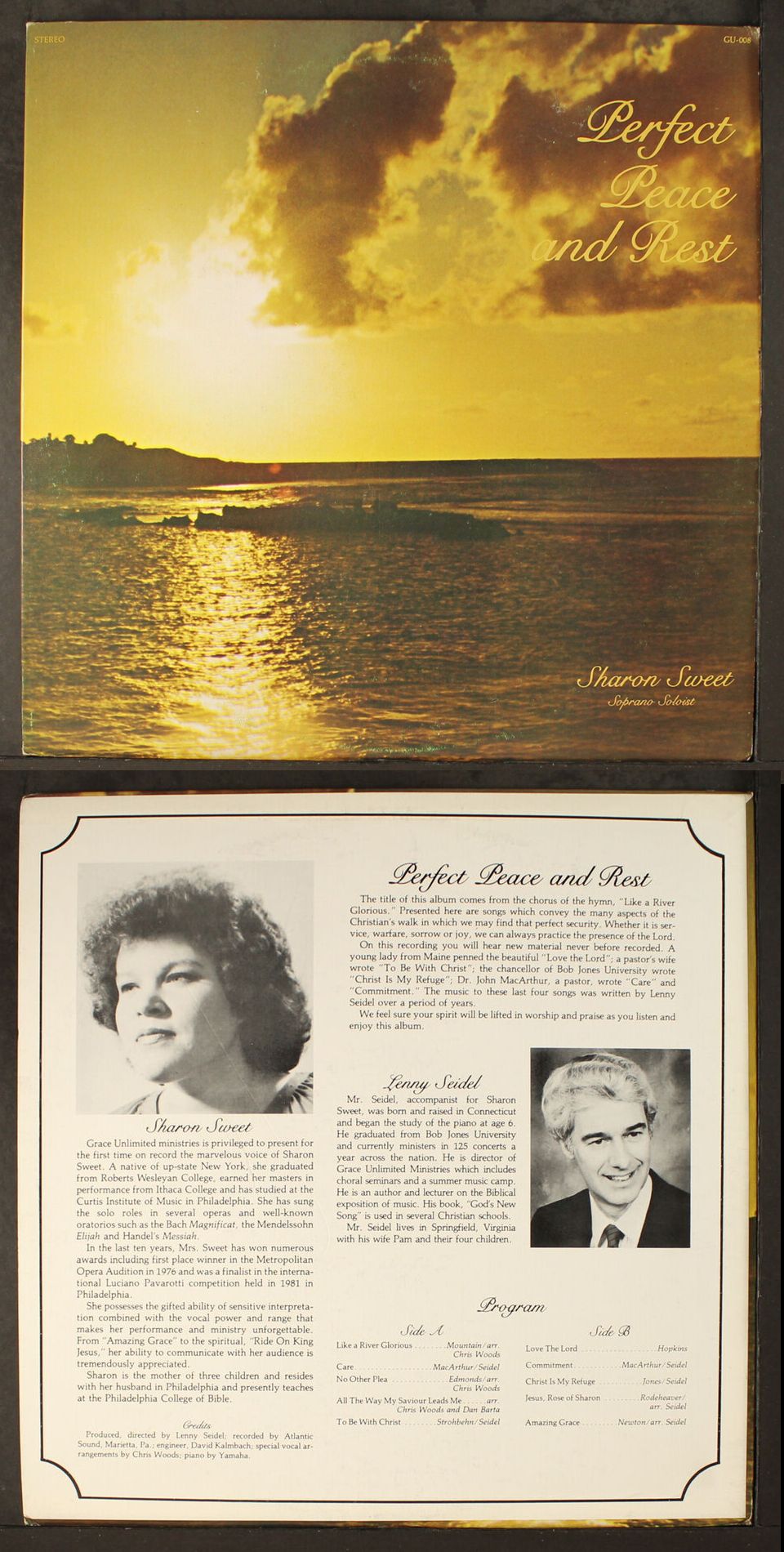

Sharon Sweet (born August 16, 1951 in Gloversville, NY) is an American dramatic soprano. She has appeared in leading roles in several major venues in Europe and the United States and has made several recordings, in particular Lohengrin, Der Freischütz, Don Giovanni, and Il Trovatore. In 1999, she accepted a full-time teaching position at Westminster Choir College of Rider University. In a column in Opera News, Sweet stated that she made the move out of frustration with the current operatic scene which emphasized physical appearance over voice. She cited her struggles with Hashimoto's syndrome, a thyroid condition. Her father had started a career as a lyric tenor, but abandoned it after serving in World War II. At age five, Sharon began studying the piano, which she had to give up after an accident. She studied singing, and then spent one year as a music teacher at a public school. After winning the Metropolitan Opera auditions, she studied at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia with Margaret Harshaw, then in New York with Marinka Gurewich [brief biography is shown in the box below]. During that time, she worked as a teacher of singing and music theory at the University of New York, and conducted the University Choir. At 24, she married a Presbyterian minister who came from her hometown. She lived in Philadelphia, giving private evenings of songs and arias, and in 1985 went to West Germany. There, she attracted a sensation when she stepped in a concert in Munich as Aïda. From 1986–88 she was engaged at the Opera House in Dortmund, where she sang Elisabeth in Tannhäuser. She also was a member of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, with whom she toured to Japan in 1987. That same year she performed at the Paris Grand Opera as Elisabetta in Don Carlos. In 1987-1988 Sweet appeared at the Staatsoper in Hamburg as Elisabetta, Leonora in Il Trovatore, and Elisabeth in Tannhäuser. She sang at the Staatstheater Braunschweig in 1988 as Desdemona in Verdi's Otello. At the 1987 Salzburg Festival she was heard as a soloist in the Stabat Mater by Dvořák. That same year she sang Gurrelieder by Schoenberg in Munich under the baton of Zubin Mehta. In 1988 she appeared at the Vienna State Opera as Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, and in Brussels as Norma in a concert performance. In 1989 Sweet made her US debut at the San Francisco Opera as Aïda. In 1990 she was a guest performer at the Arena di Verona as Aïda, and in 1991 in Montpellier as Leonora in Il Trovatore. In 1992 she appeared at the State Operas of Vienna and Dresden, and at the opera in Dallas. In 1993 she sang in the amphitheater of Caesarea as Aïda, and at the Festival of Orange as Leonora, and in Munich as Desdemona. In 1992 she sang at the Lyric Opera of Chicago as Amelia in Verdi's Un ballo in maschera. Sweet made her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1990 as Leonora, and over the next decade played 8 different Verdi, Mozart, Wagner, and Puccini roles with the company, including Lina in the Met premiere of Verdi's Stiffelio during the 1993/94 season. She also played Leonora in a new production of La forza del destino during the 1995/96 season. Both of these productions were directed by Giancarlo del Monaco. In 1994 Sweet made her debut at Covent Garden Opera London as Turandot,

and in 1995 was Aïda, and in 1996 again as Turandot. In 1995 she sang

at the Teatro Comunale Bologna as Norma, and at the State Theater in Hanover

as Tosca. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

|

Marinka Gurewich (1902, Bratislava – December 23, 1990, Manhattan)

was an American voice teacher and mezzo-soprano of Jewish-Czech descent. She is best remembered for teaching several

successful opera singers, including Martina Arroyo, Marcia

Baldwin, Grace Bumbry,

Joy Clements, Ruth Falcon, Melvyn Poll, Florence Quivar, Diana

Soviero, and Sharon Sweet. Born Marinka Revész in Bratislava, Gurewich trained as a

singer and pianist at the Berlin University of the Arts where she was a pupil

of Lula Mysz-Gmeiner. She also studied privately with Elena Gerhardt and

Anna von Mildenburg in Munich. Her

career as a singer in Germany was hindered by World War II, and she

fled Europe for the United States in 1940. Prior to the war she had appeared in concerts and recitals in Europe. After coming to the United States, she appeared in a few recitals and concerts in New York City, but ultimately began devoting her time to teaching. During the 1960s and 1970s she taught on the voice faculties of the Manhattan School of Music and the Mannes College of Music. She continued to teach privately up until her death. |

See my interviews with Paul Plishka

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at her hotel near the Ravinia Festival on July 20, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB a few week later. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.