|

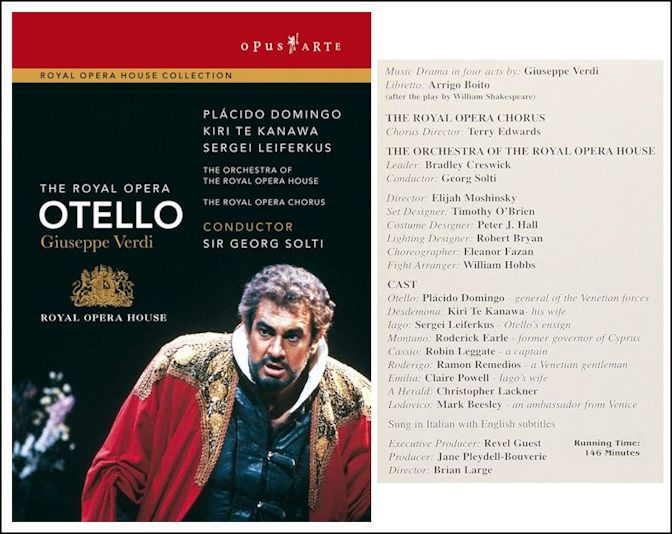

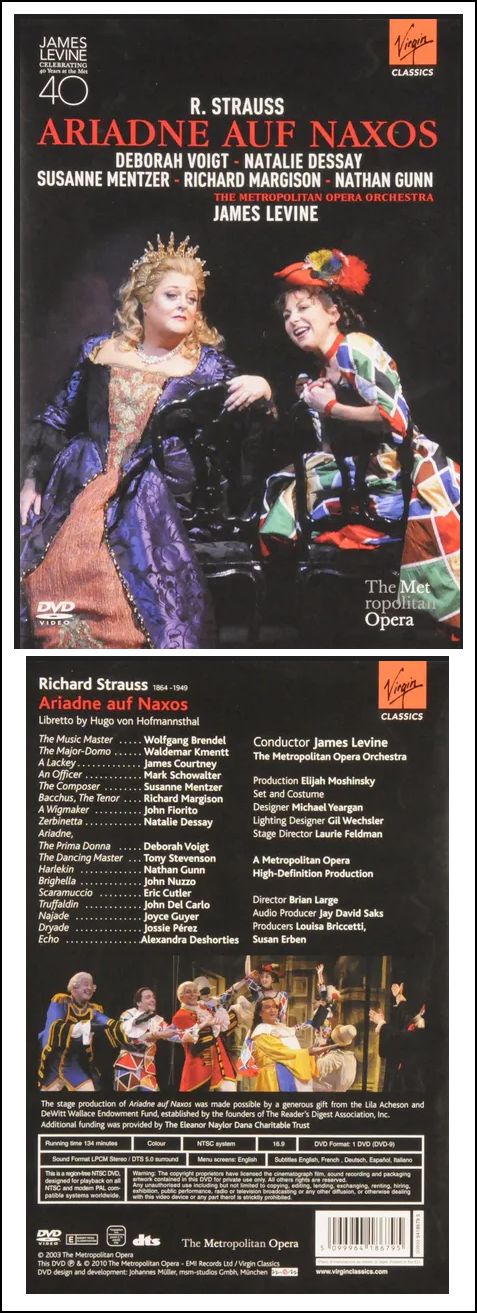

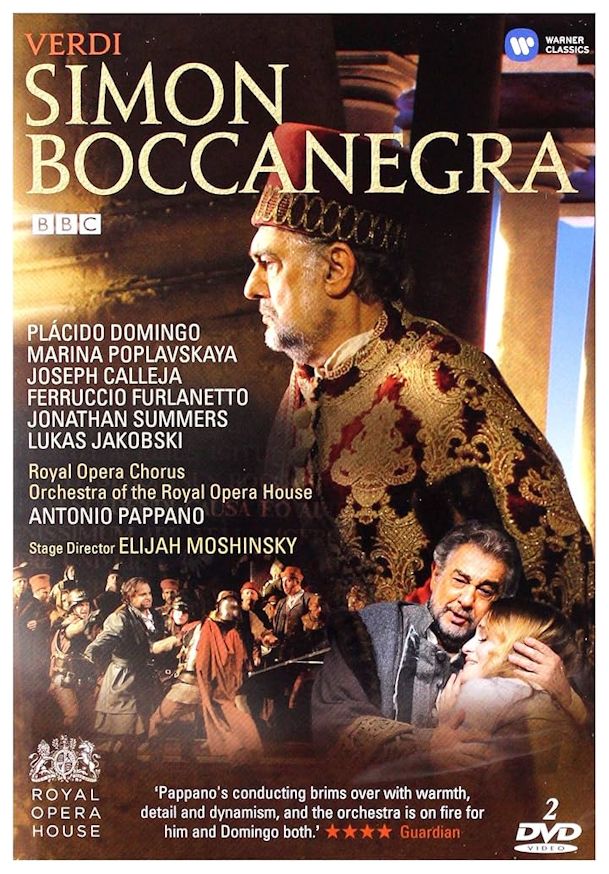

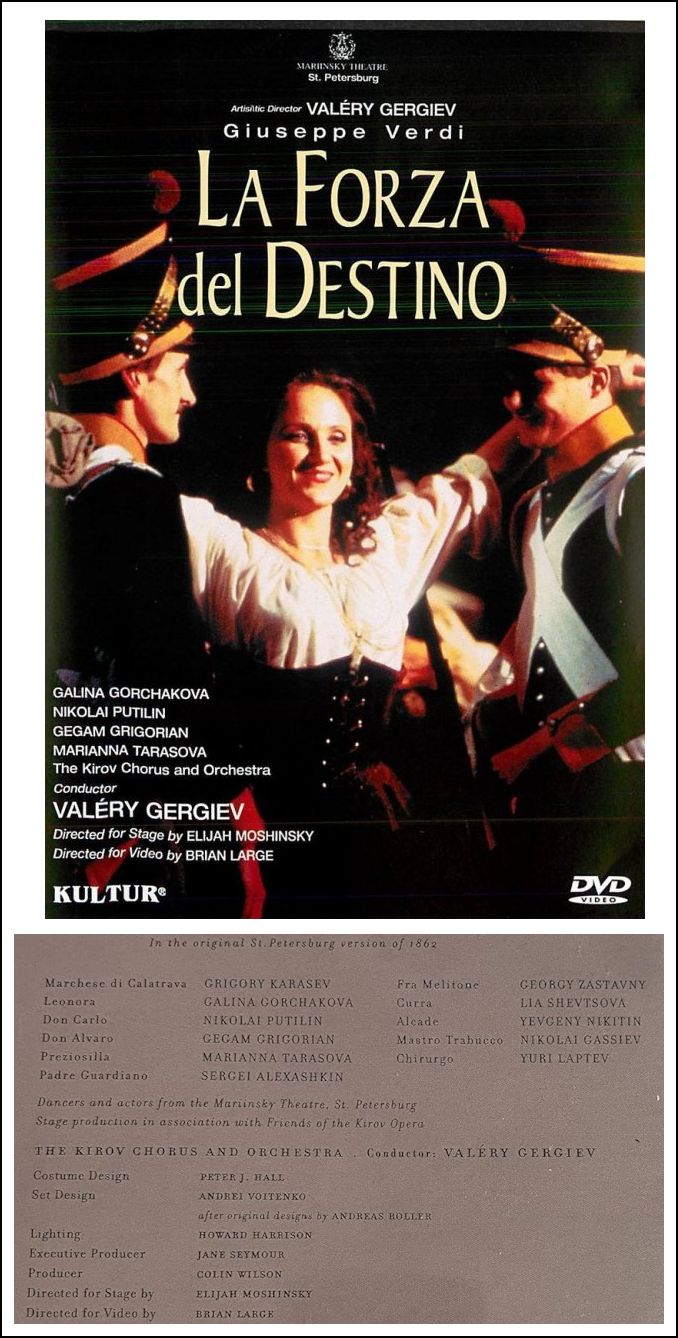

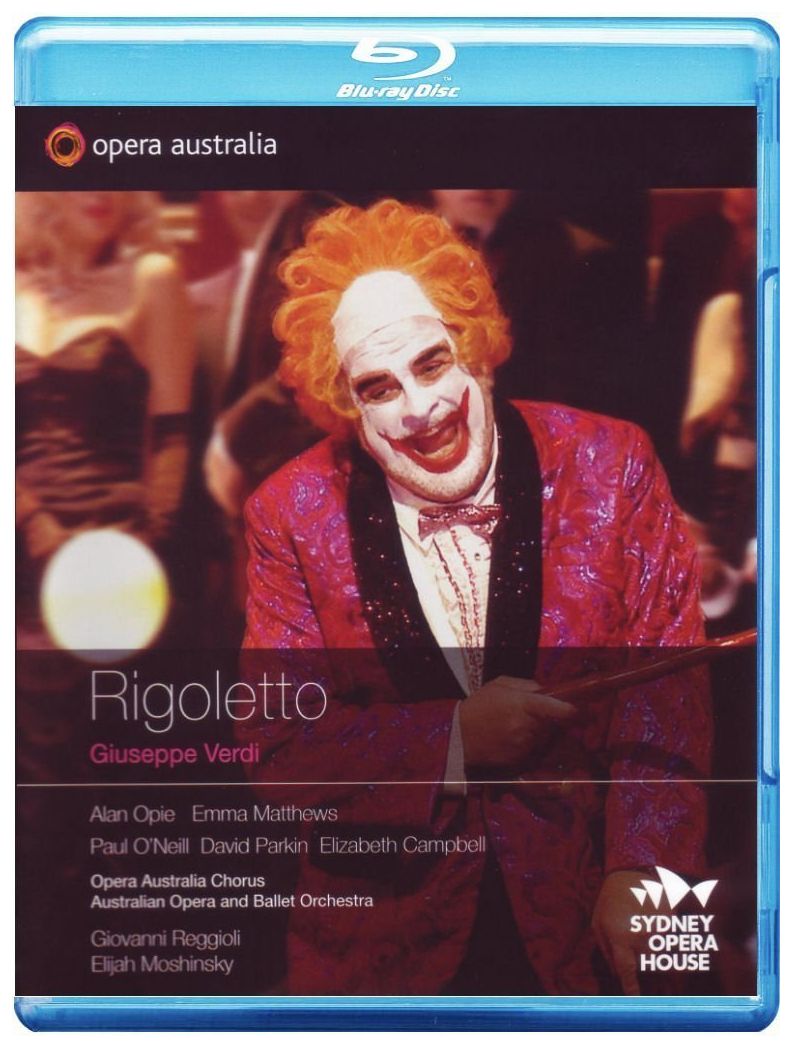

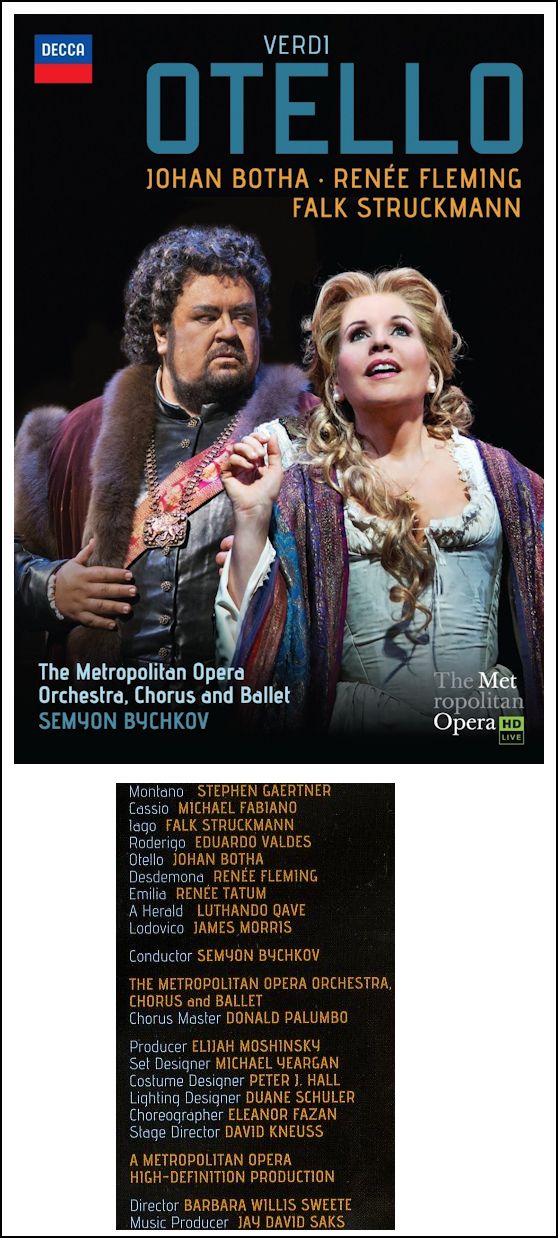

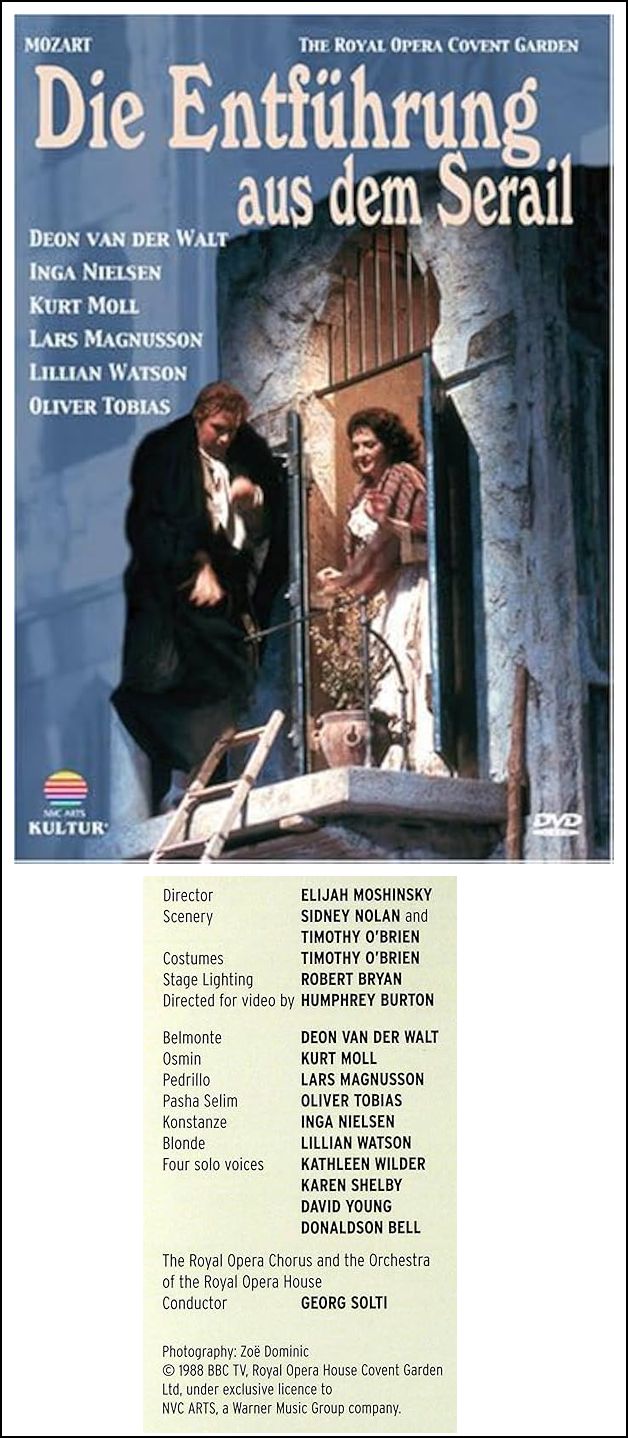

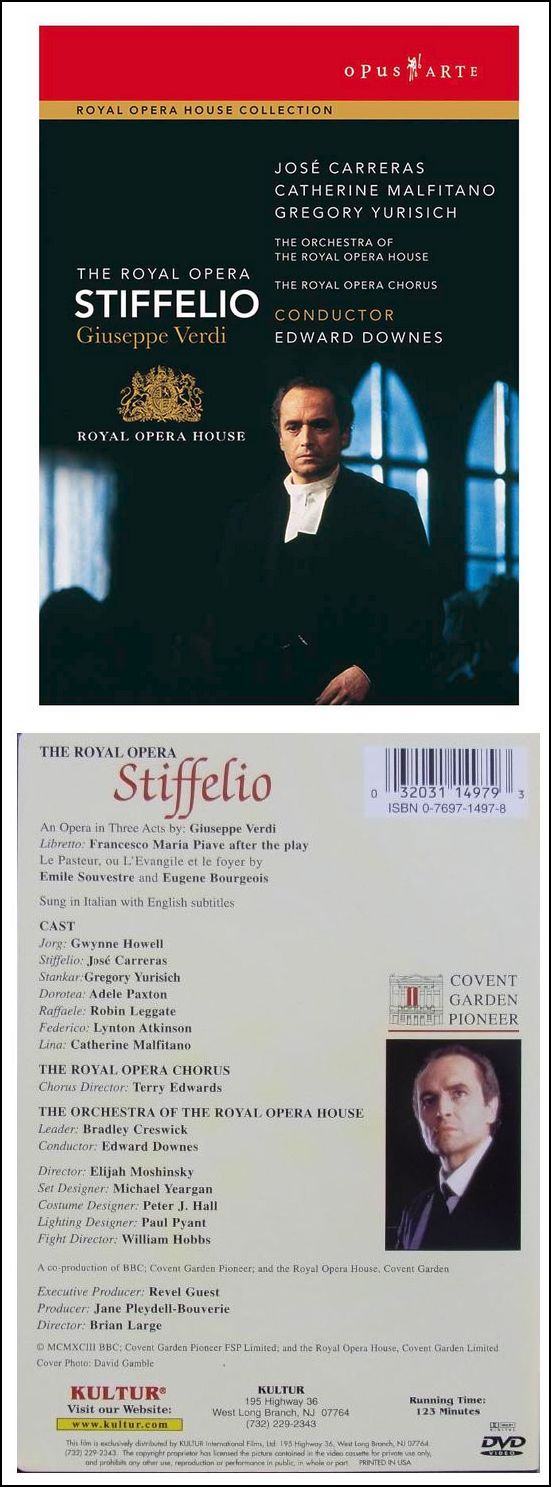

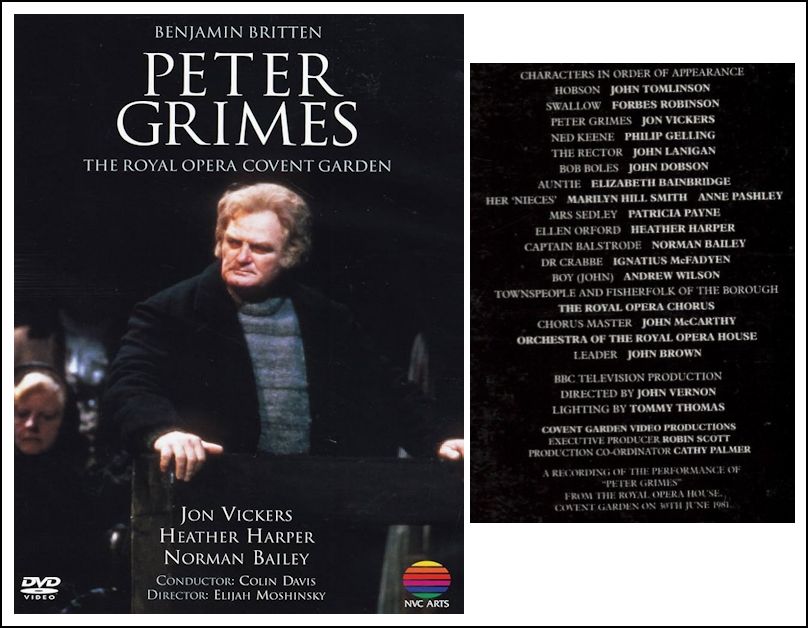

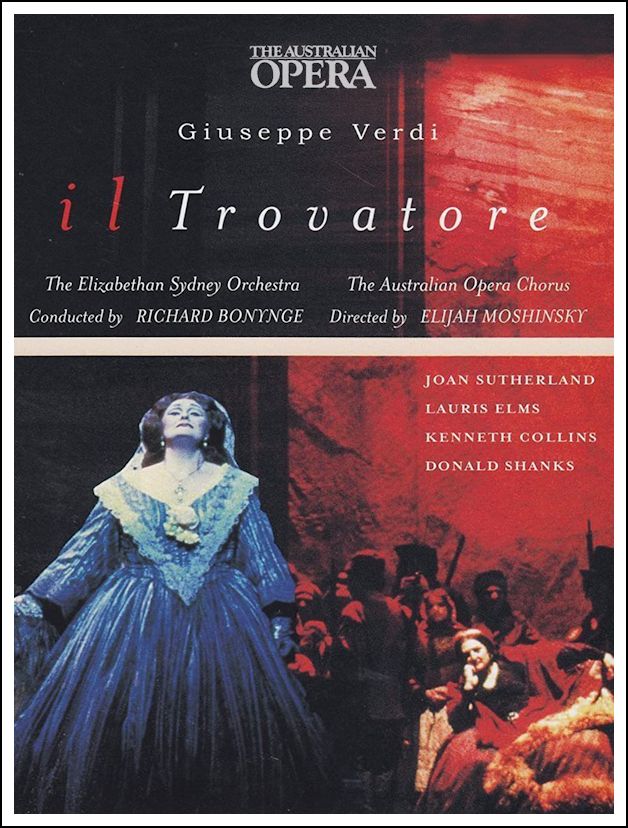

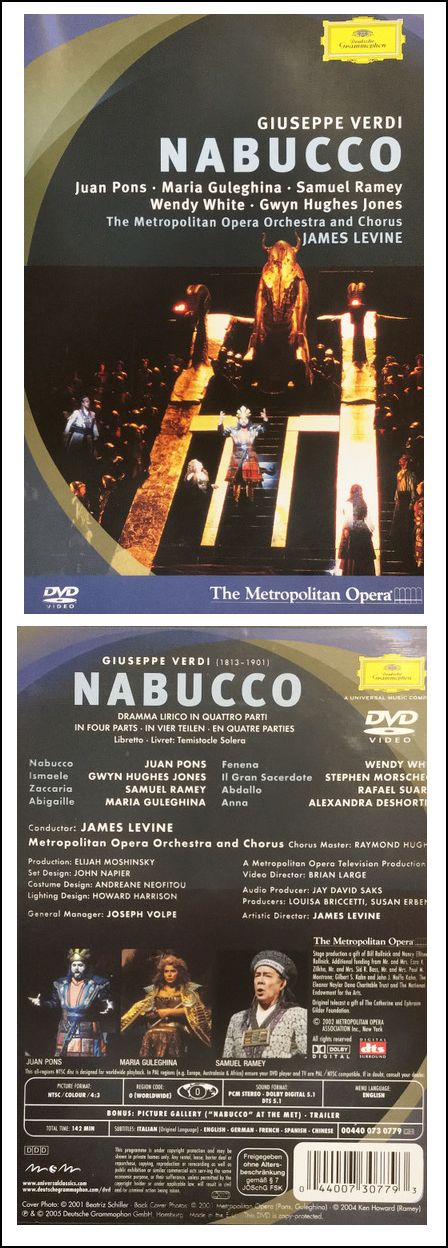

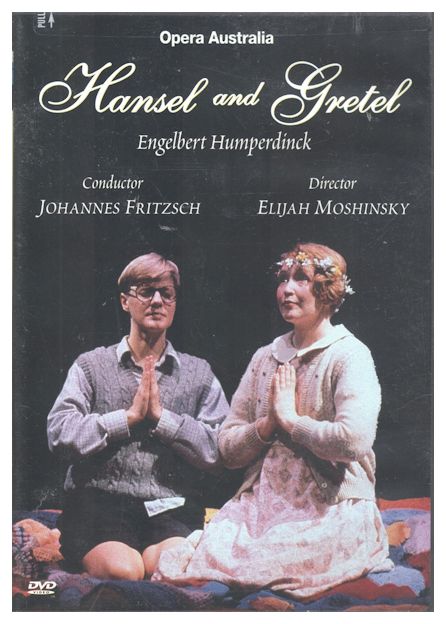

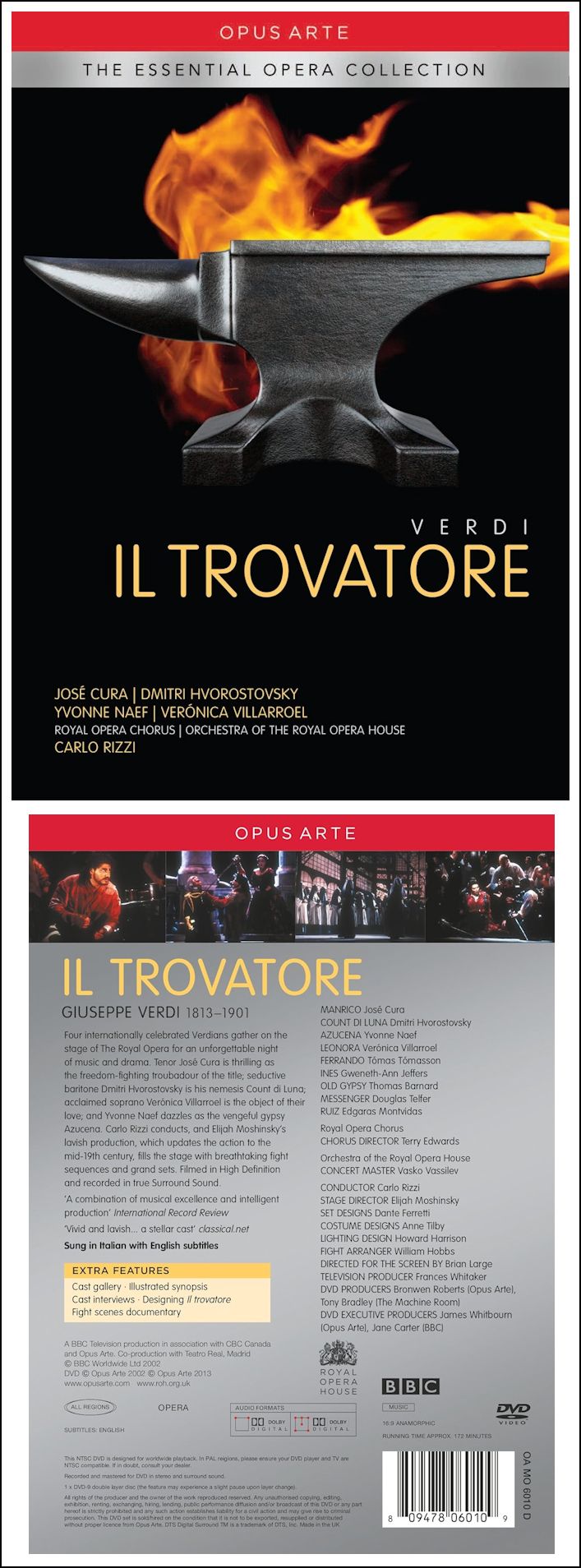

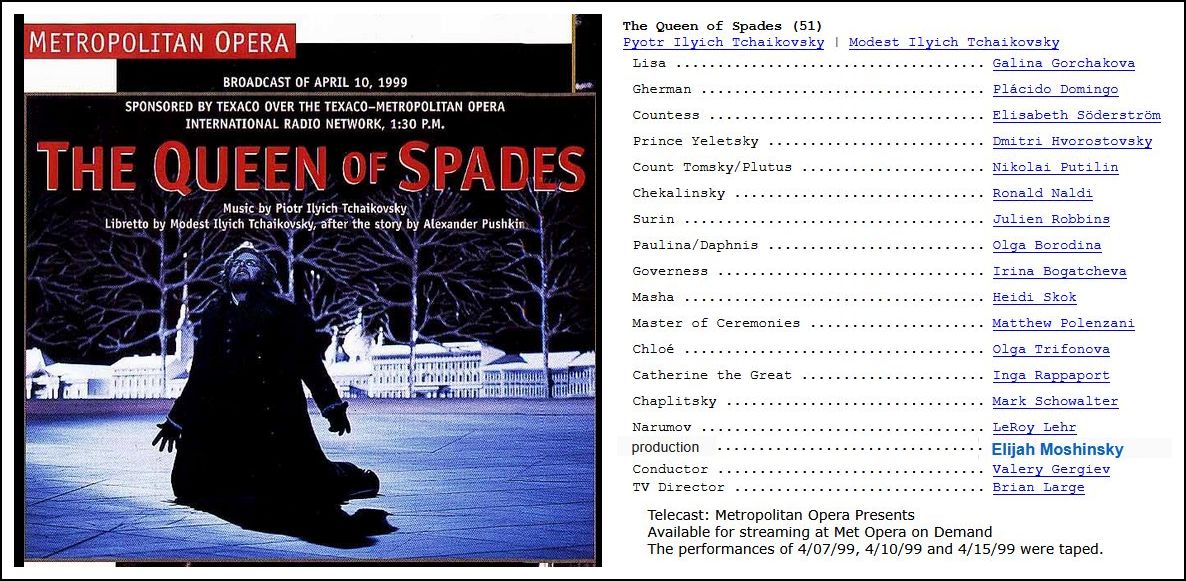

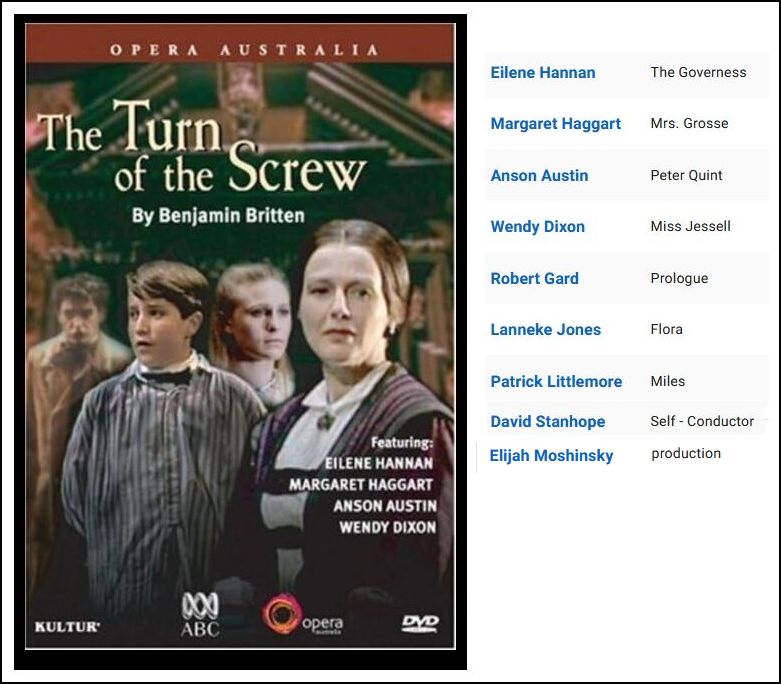

Elijah Moshinsky enjoyed a long and prolific career spanning more than forty years as a director of both opera and theatre. Renowned particularly for his interpretations of Verdi, his productions have been seen throughout the world and enjoy frequent revival. His work encompasses a large and diverse repertoire, with a focus on Mozart, Janáček, Britten, Tchaikovsky, Wagner and Strauss, but also including Mussorgsky, Poulenc and Ligeti. He has three times been the winner of the Laurence Olivier Award for Best Opera, for his productions of Lohengrin, Stiffelio and The Rake’s Progress. Elijah Moshinsky developed ongoing relationships with opera houses throughout the world, including, in particular, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden and the Metropolitan Opera, New York, for whom he has directed many celebrated productions. His first major opera production was Peter Grimes for the Royal Opera House in 1975, and subsequent work there includes Lohengrin, The Rake’s Progress, Macbeth, Samson et Dalila, Samson, Tannhäuser, Tristan und Isolde, Otello, Attila, Entführung aus dem Serail, Stiffelio, Aida, Simon Boccanegra, I Masnadieri and Il trovatore. His later work at ROH has included revival productions of Otello and Lohengrin, and Moshinsky returned to Covent Garden in 2013 for a further revival of his Simon Boccanegra, conducted by Sir Antonio Pappano. Later work at the Metropolitan Opera has included revival stagings of The Makropulos Case, Ariadne auf Naxos and Otello, whilst other productions in New York include Un ballo in maschera, Nabucco, Queen of Spades, Lohengrin, and Luisa Miller. Moshinsky has also enjoyed ongoing relationships with opera companies including Opera Australia (Boris Godunov, Il trovatore, Werther, La Traviata, Rigoletto, Les dialogues des Carmélites and Barber of Seville). Other houses include The Lyric Opera of Chicago, where he staged a critically acclaimed revival of his Simon Boccanegra in Autumn 2012, Houston Grand Opera, Los Angeles Opera, Welsh National Opera, English National Opera (including the British première of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre), Wiener Staatsoper, Grand Théâtre de Genève, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino and the Adelaide and Holland Festivals. Moshinsky directed a large range of theatre and TV productions. Among his West End productions are Troilus and Cressida and The Force of Habit for the National Theatre, Three Sisters (Albery), Shadowlands and Cyrano de Bergerac (Haymarket) and Much Ado About Nothing (Strand). For the BBC, his directing work includes Genghis Cohn, Brazen Hussies, Anorak of Fire, Mozart in Turkey, as well as an Omnibus documentary on divas. Born in Shanghai, and raised in Melbourne Australia, Elijah Moshinsky graduated from the University of Melbourne and studied subsequently at St Anthony’s College Oxford. Whilst there, he directed a production of As You Like It for the Oxford and Cambridge Shakespeare Company, which resulted in him being offered a position as a staff producer at the Royal Opera House. == Biography above from the website of Opera

Australia

== Below are a few more details from other sources Moshinsky's Russian Jewish parents had fled from Vladivostok to the French Concession of Shanghai, where Elijah was born on January 8, 1946. When he was five years old, the family moved to Melbourne. He attended Camberwell High School and then was an under-graduate resident at Ormond College, where in 1965 he was the set designer of a stage adaptation of Kafka's The Trial. Moshinsky supported himself as an undergraduate by playing the third flute at the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. In 1969, he directed Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape with Max Gillies at the Alexander Theatre at Monash University. He graduated from the University of Melbourne and in 1973 won a scholarship to St Antony's College, Oxford, where he specialised in the study of Alexander Herzen. While still at St Antony's, Moshinsky directed a production of As

You Like It for the Oxford and Cambridge Shakespeare Company. When Sir John Tooley, the General Director

at Covent Garden, saw the play, he offered Moshinsky a post as a staff

producer for The Royal Opera. In January 2021, Moshinsky had a fall at his London home, and was

taken to hospital where he contracted COVID-19 during the COVID-19 pandemic

in the United Kingdom. He died in London on January 14, 2021. |

Robert Bolt (Aug. 15, 1924, Sale, near Manchester, England - Feb. 20, 1995, near Petersfield, Hampshire) was an English screenwriter and dramatist noted for his epic screenplays. Bolt began work in 1941 for an insurance company, attended Victoria University of Manchester in 1943, and then served in the Royal Air Force and the army during World War II. After earning a B.A. in history at Manchester University in 1949, he worked as a schoolteacher until 1958, when the success of his play Flowering Cherry (London, 1957), a Chekhovian study of failure and self-deception, enabled him to leave teaching. Bolt’s most successful play was A Man for All Seasons, a study of the fatal struggle between Henry VIII of England and his lord chancellor, Sir Thomas More, over issues of religion, power, and conscience. The play drew intense acclaim in productions at London (1960) and New York City (1961). Bolt wrote the screenplays for director David Lean’s epic films Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965) and then adapted A Man for All Seasons for director Fred Zinnemann’s motion-picture version of the play in 1966. His other screenplays included Ryan’s Daughter (1970), which was directed by Lean; Lady Caroline Lamb (1972), which Bolt himself directed; The Bounty (1984); and The Mission (1986). * * *

* *

Pountney was born in Oxford and was a chorister at St John's College, Cambridge (1956-61). He was then educated near Oxford at Radley College (1961-66), and then returned to St John's College, Cambridge to read his degree. His first major breakthrough came in 1972 with his production of Káťa Kabanová for the Wexford Festival. From 1975 to 1980, he was the Director of Productions at Scottish Opera, and, from 1982 to 1993, Director of Productions at English National Opera, where he directed over twenty operas. From 1993 to 2004, he worked as a free-lance director at the Zurich Opera, the Vienna State Opera, the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, and other houses in America, Japan, and the United Kingdom. He has also directed at De Nederlandse Opera and Opera Australia. In December 2003 he became the Intendant of the Bregenz Festival, a post he held until 2014. In April 2011 he was named head of the Welsh National Opera with his appointment as chief executive and artistic director. He has translated opera librettos into English from Russian, Czech, German, and Italian. He wrote the libretto for and directed Elena Langer's opera Figaro

Gets a Divorce, which was premiered at the Welsh National Opera in

February 2016. To great

critical acclaim he directed Zandonai's Francesca da Rimini at

La Scala Opera House, Milan in 2018. Later that year at Strasbourg he directed

works by Kurt Weill and Arnold Schoenberg, Das Mahagonny Songspiel, Pierrot

Lunaire and Die 7 Todsunden.

|

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 7, 1985. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1991, 1996, and 1997. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.