|

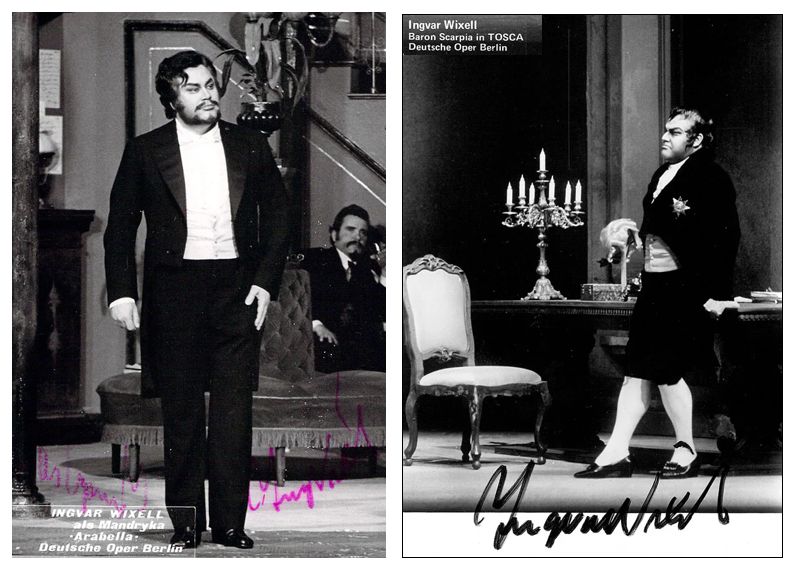

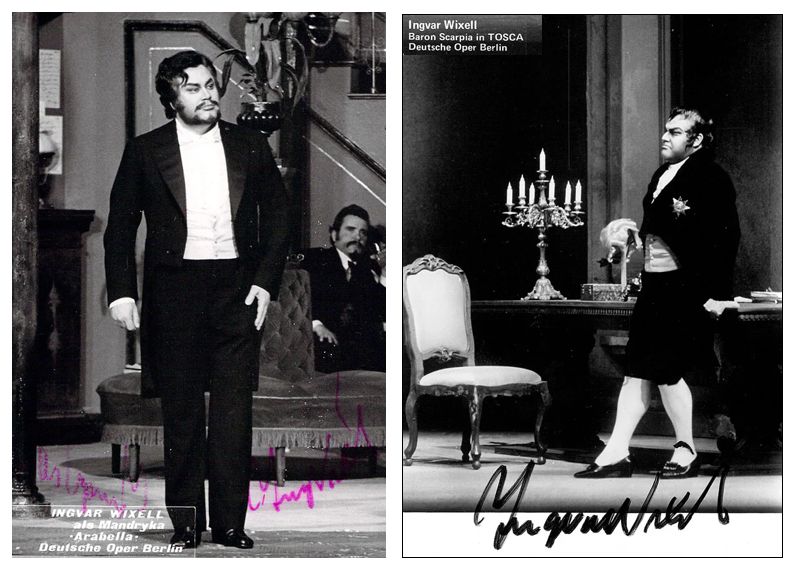

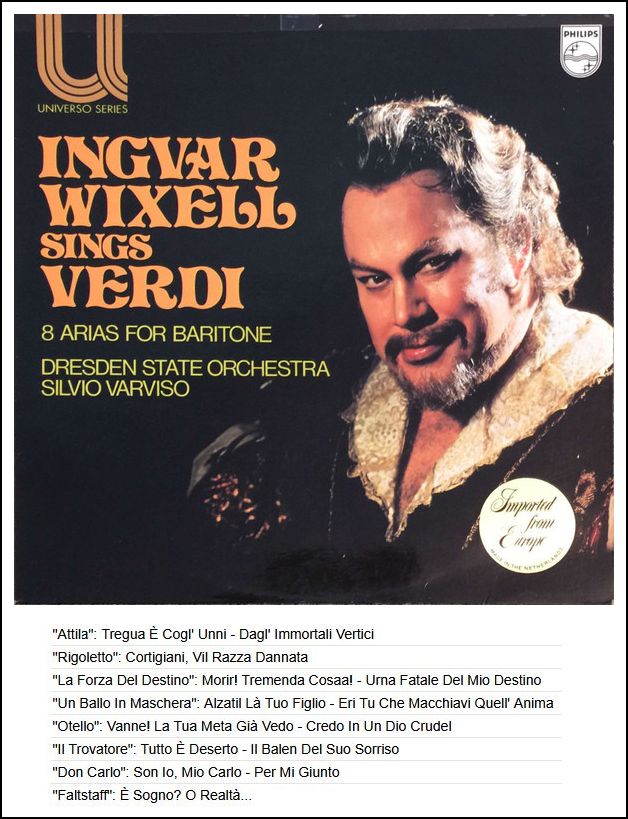

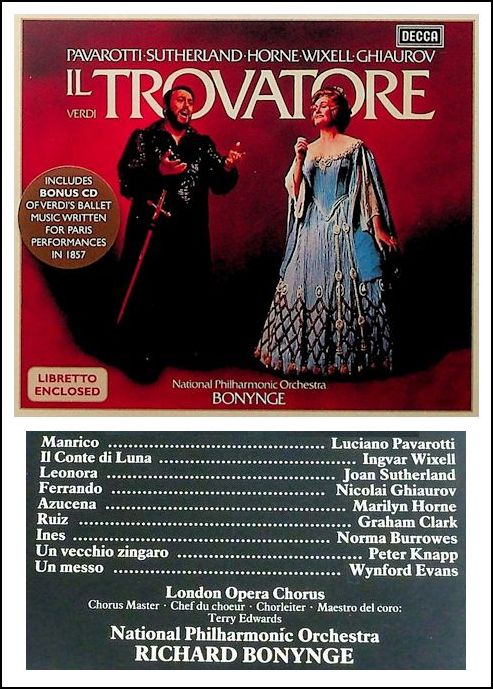

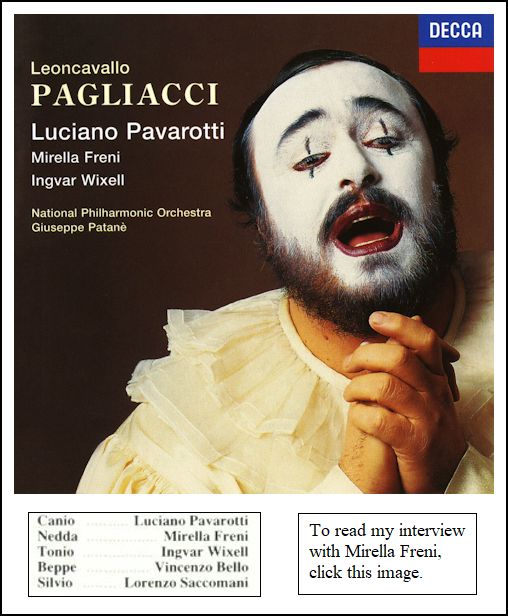

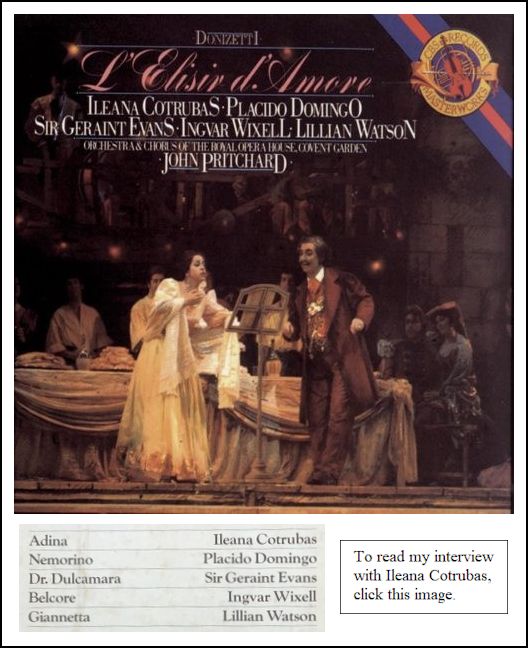

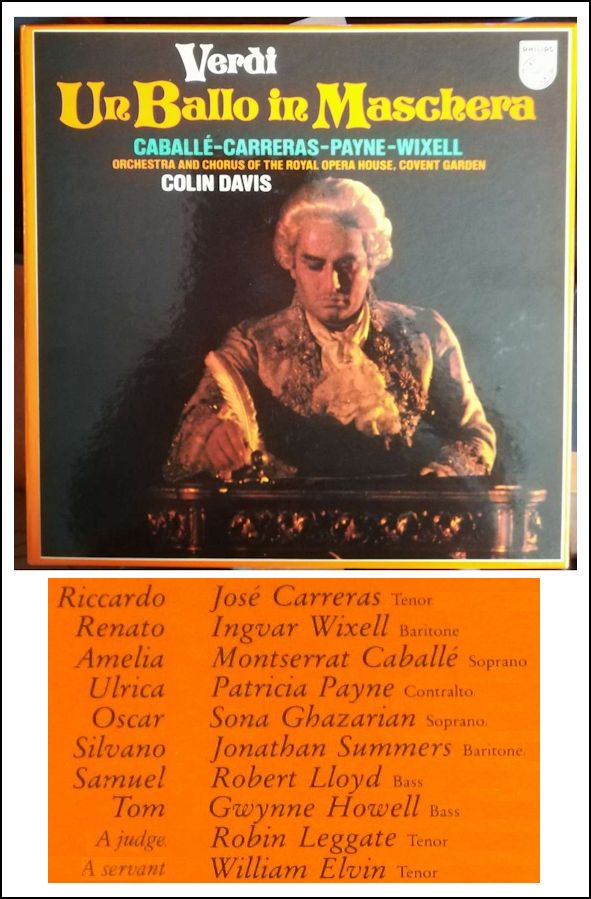

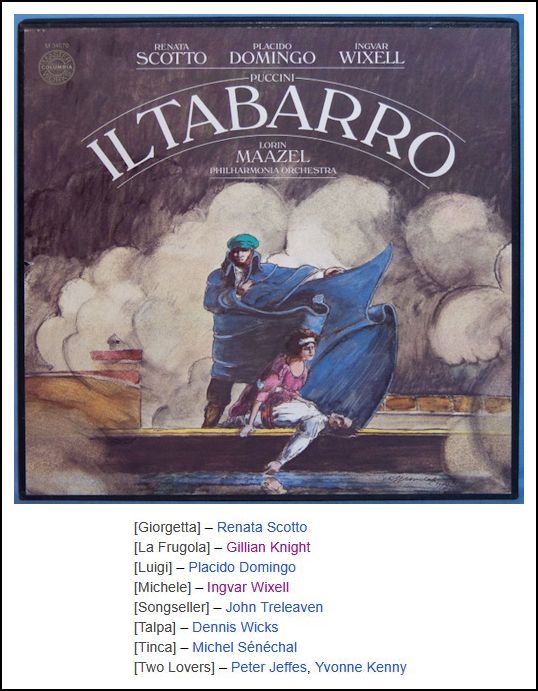

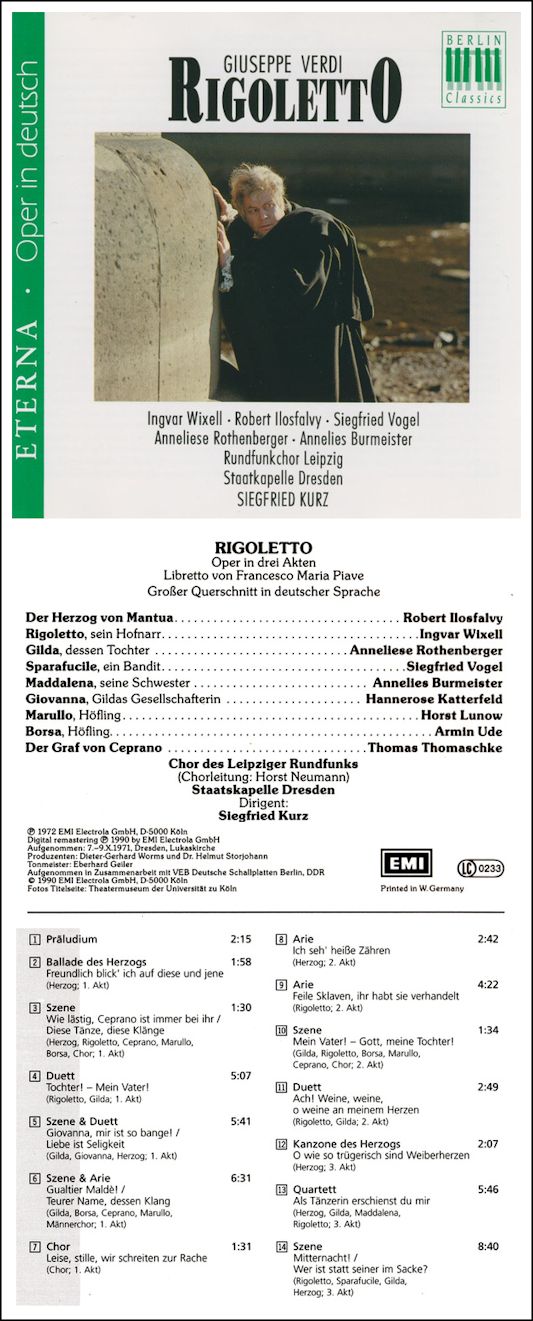

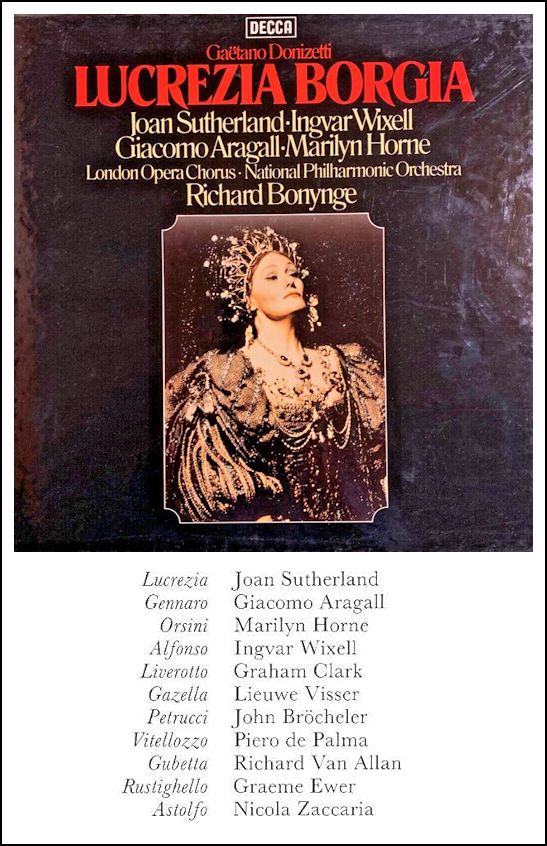

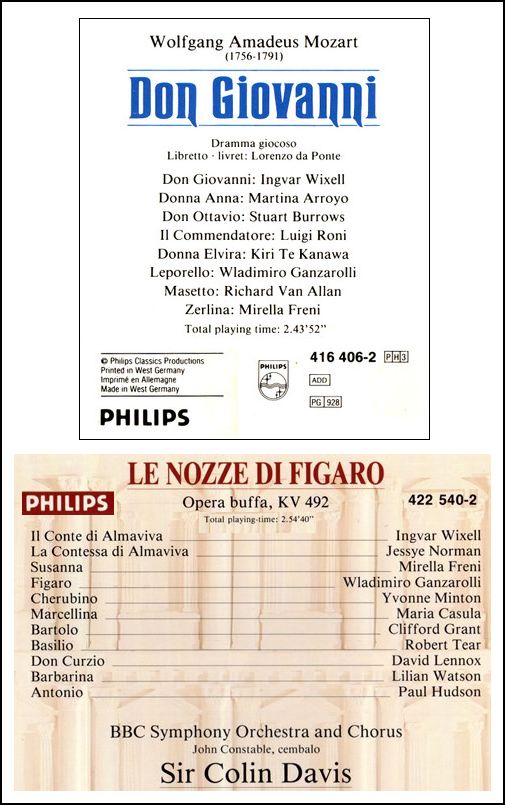

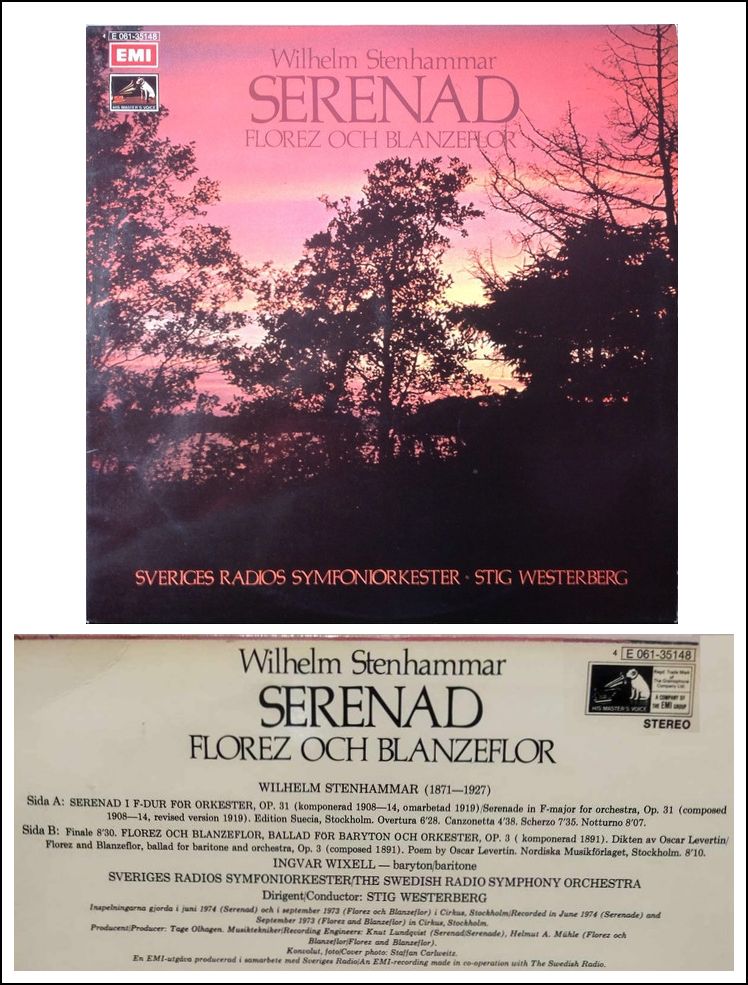

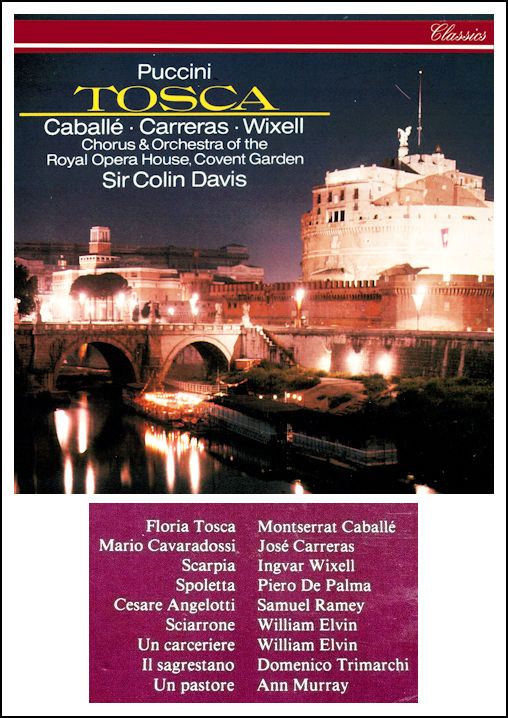

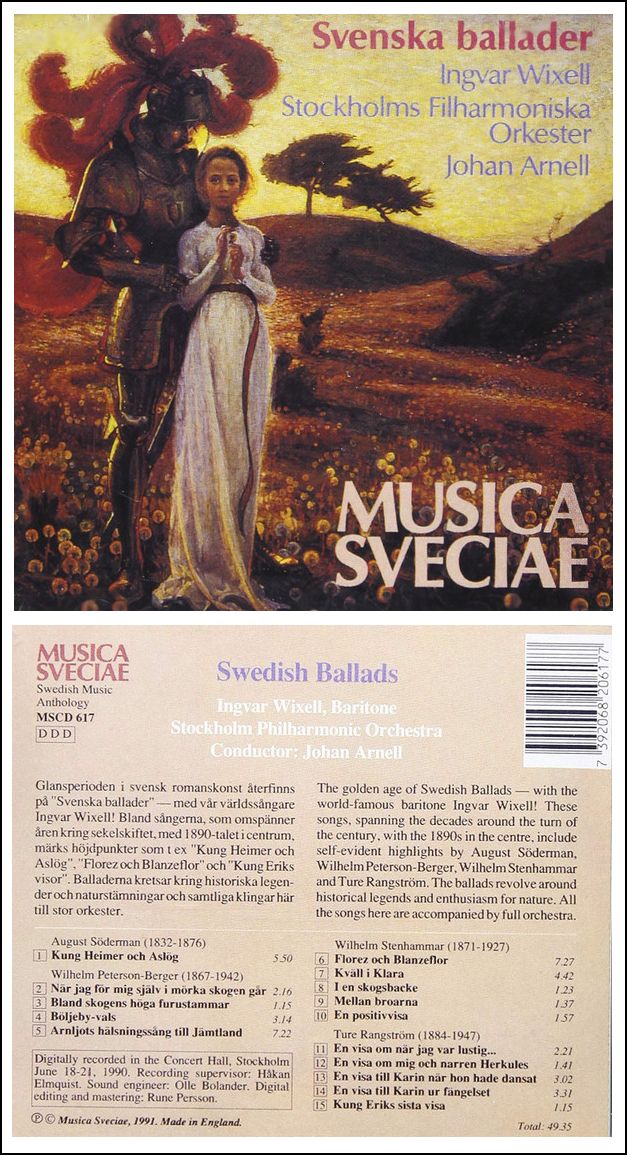

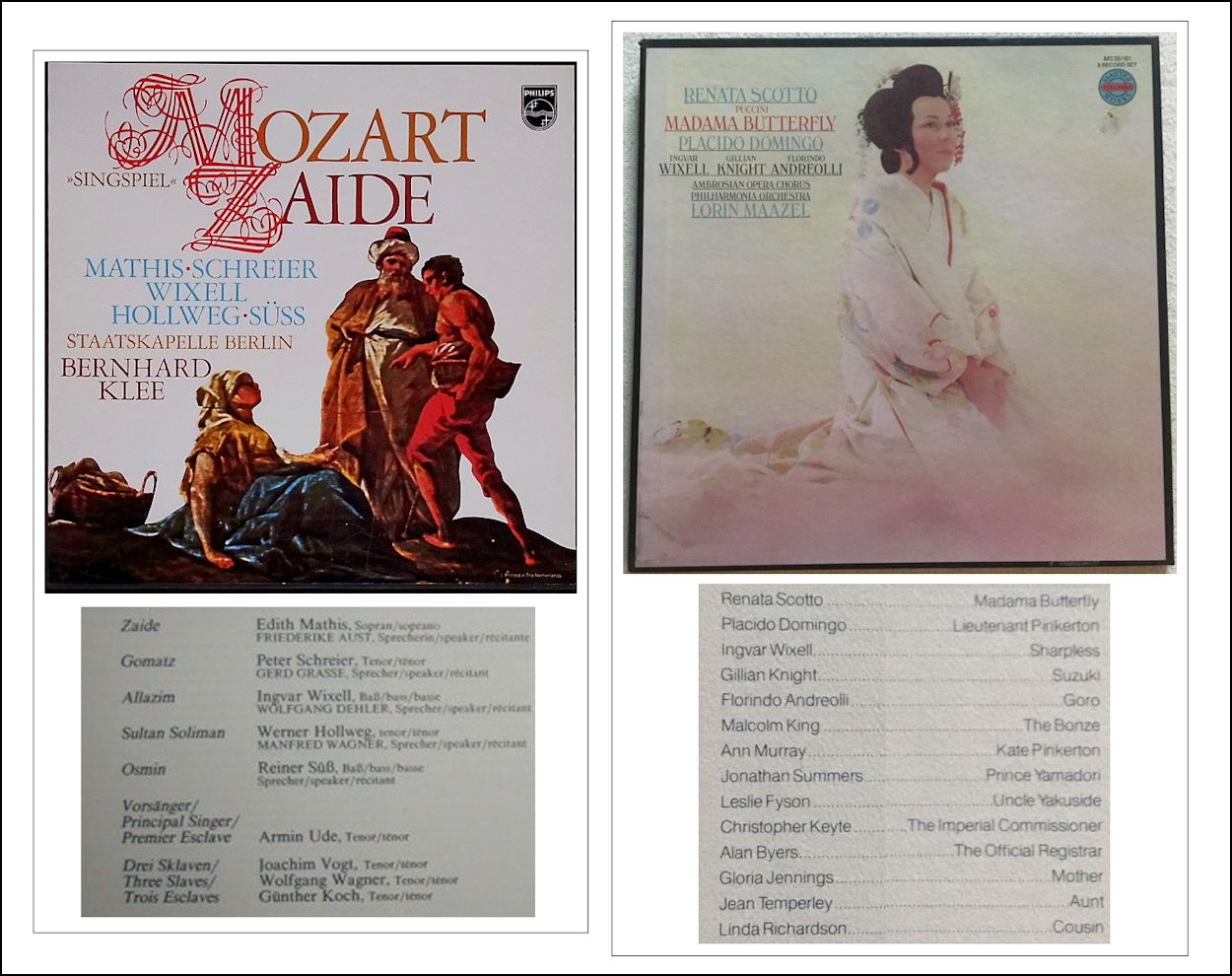

Karl Gustaf Ingvar Wixell (May 7, 1931 – October 8, 2011) was a Swedish baritone who had an active international career in operas and concerts from 1955 to 2003. He mostly sang roles from the Italian repertory, and, according to The New York Times, "was best known for his steady-toned, riveting portrayals of the major baritone roles of Giuseppe Verdi — among them Rigoletto, Simon Boccanegra, Amonasro in Aida, and Germont in La traviata". He was the Swedish entrant in the Eurovision Song Contest 1965. Ingvar Wixell was born in Luleå. After studies at the Stockholm Academy of Music, he made his debut in Gävle in 1952, then in 1955 as Papageno in Mozart's The Magic Flute at the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm where he was member of the company until 1967. He made his British debut during the Royal Swedish Opera's visit to the Edinburgh International Festival in 1959. Wixell returned with this company to Royal Opera House in 1960, and sang Guglielmo at Glyndebourne and at the Proms in 1962. For the Royal Opera, London he sang Boccanegra in 1972. In America he appeared at Chicago Lyric Opera, San Francisco, and the Metropolitan Opera. He was engaged at the Deutsche Oper Berlin in 1967 where he was a member for more than 30 years. At Salzburg he sang a noted Pizarro at the Festival, where he appeared from 1966 to 1969, and at Bayreuth he sang the Herald in Lohengrin (1971). Among other roles, Wixell sang Figaro in Rossini's The Barber of Seville, Escamillo in Bizet's Carmen, Amonasro in Verdi's Aida, Baron Scarpia in Puccini's Tosca, and the title roles in Verdi's Rigoletto, Simon Boccanegra, Mozart's Don Giovanni, Verdi's Falstaff and Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin. |

|

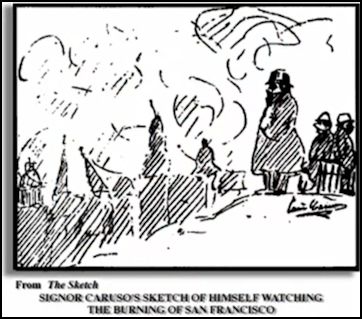

Auber wrote Gustave III, ou Le bal masqué as a grand opera in five acts to a libretto by Eugène Scribe, about some aspects of the real-life assassination of Gustav III, King of Sweden. The major aspects of the plot can be found first in Giuseppe Verdi's planned opera, Gustavo III, which was never performed as written, but whose major elements were incorporated into a revised version of the story in the opera which eventually became Un ballo in maschera. The opera received its first performance at the Salle Le Peletier of the Paris Opéra on 27 February 1833, and was a major success for the composer, with 168 performances until 1853. |

Rondò Veneziano and is an Italian chamber orchestra,

specializing in Baroque music, playing original instruments, but

incorporating a rock-style rhythm section of synthesizer, bass guitardrums,

led by Maestro Gian Piero Reverberi [photo at left], who is

also the principal composer of all of the original Rondò Veneziano

pieces. The unusual addition of modern instruments, more suitable for

jazz, combined with Reverberi's arrangements and original compositions,

have resulted in lavish novel versions of classical works over the years.

As a rule in their concert tours, the musicians, mostly women, add to

the overall Baroque effect wearing Baroque-era attire and coiffures.

Rondò Veneziano and is an Italian chamber orchestra,

specializing in Baroque music, playing original instruments, but

incorporating a rock-style rhythm section of synthesizer, bass guitardrums,

led by Maestro Gian Piero Reverberi [photo at left], who is

also the principal composer of all of the original Rondò Veneziano

pieces. The unusual addition of modern instruments, more suitable for

jazz, combined with Reverberi's arrangements and original compositions,

have resulted in lavish novel versions of classical works over the years.

As a rule in their concert tours, the musicians, mostly women, add to

the overall Baroque effect wearing Baroque-era attire and coiffures.The orchestra's first decade of albums included only entirely original compositions in the style of the baroque rondo, 'a musical composition built on the alternation of a principal recurring theme and contrasting episodes'. In later years, in addition to many new and original albums continuing Gian Piero Reverberi's own unique Rondo style and tradition, Rondò Veneziano also brought their fusion of classical and contemporary instruments to a small number of albums dedicated to some of the great composers of the classical and baroque tradition. In an interview, Maestro Reverberi said on the sound of Rondò

Veneziano, "Rondò Veneziano's music is first of all positive.

Also when it seems to be sad, it's never sad. It's always positive

in a sense that at the end there's always a good future. So I think

that also the reason of the success it that it's music where you don't

have to think negative or to feel negative or if you feel negative it

should be something that brings you to think positive." The orchestra has produced 70 albums since its founding in 1979.

|

|

Drottningholms Slottsteater was built in 1766 at the request of Queen Lovisa Ulrika. The theatre is constructed of simple materials and the auditorium is playfully decorated using paint, stucco, and papier mâché. The wooden stage machinery is operated by hand. It includes wind, thunder and cloud machines, as well as traps and moving waves. About 30 stage sets have been preserved, all decorated with themes from 18th century repertoire. It seats about 400 people. The first golden age of the theatre was initiated by King Gustaf III in 1777. Up to his death in 1792, when the theatre was closed, the repertoire included Gluck’s latest works, opéras comiques, French classical dramas and pantomime ballets. When the literary historian Agne Beijer walked through the door in 1921 he discovered a sleeping beauty, untouched since the end of the 18th century. After replacing the ropes, thorough cleaning and the installation of electricity, the magnificent theatre was reopened. Now the machinery could once again perform changements à vue, i.e. open scene changes in front of the audience. In 1991 the World Heritage Committee of UNESCO designated the theatre, together with Drottningholm Palace, the Chinese Pavilion and the surrounding park, as being of international cultural heritage significance. Today the theatre offers new productions of 17th and 18th century

operas and attracts audiences from all over the world every summer.

Since 1979 the Drottningholm Theatre Orchestra has performed on period

instruments, and the repertoire includes works by Haydn, Handel,

Gluck and Mozart, as well as Rameau and Monteverdi.

|

See my interviews with Edith Mathis, and Peter Schreier

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in a dressing room backstage at Lyric Opera of Chicago on October 25, 1982. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1985, 1990, 1991, 1993, and 1996. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.