|

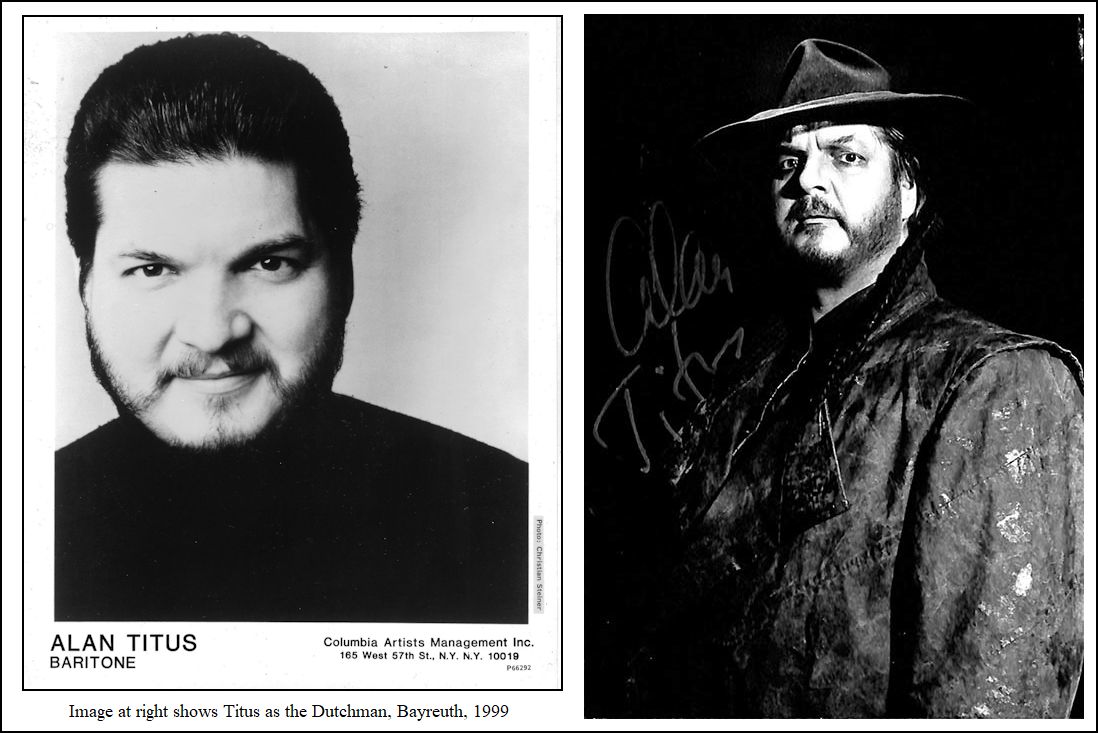

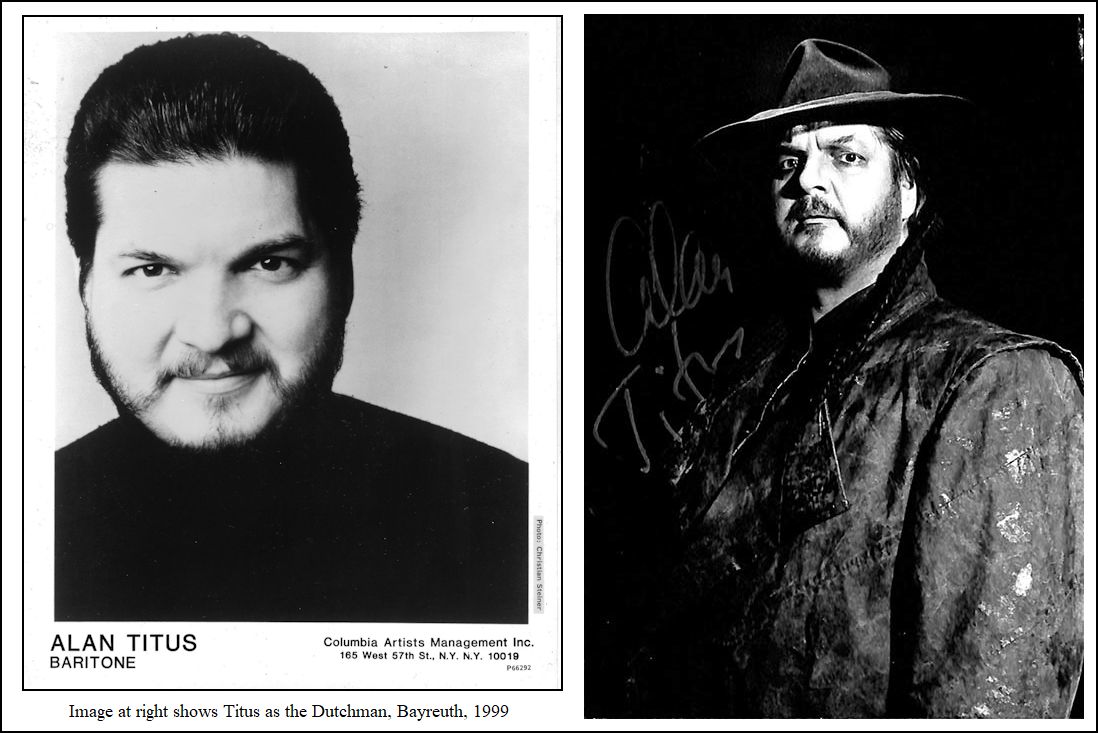

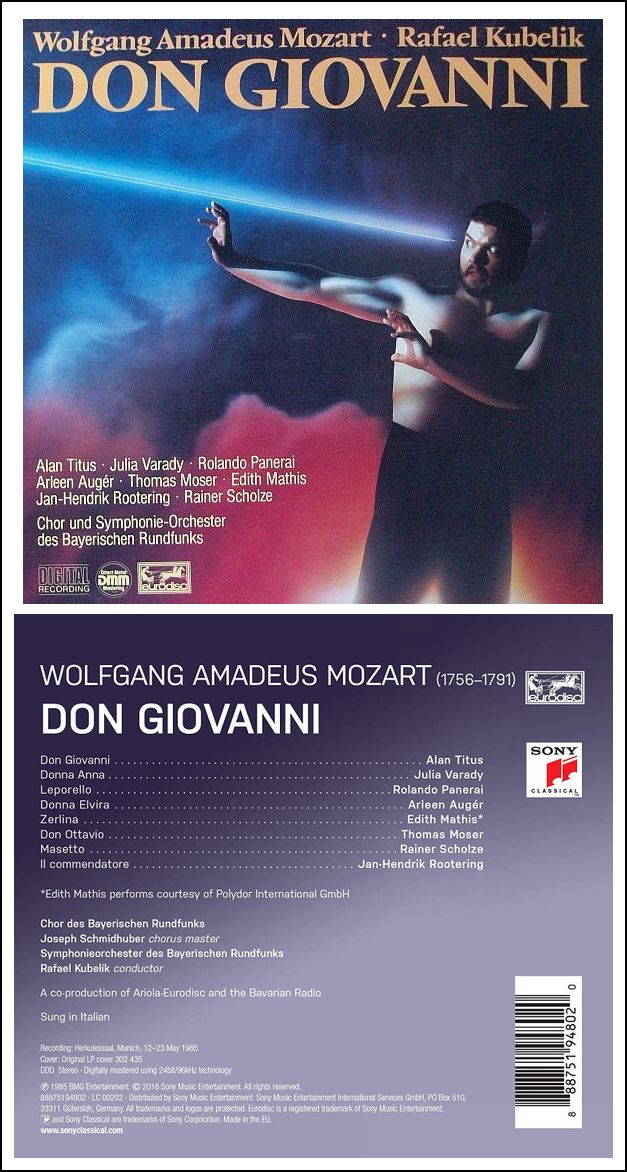

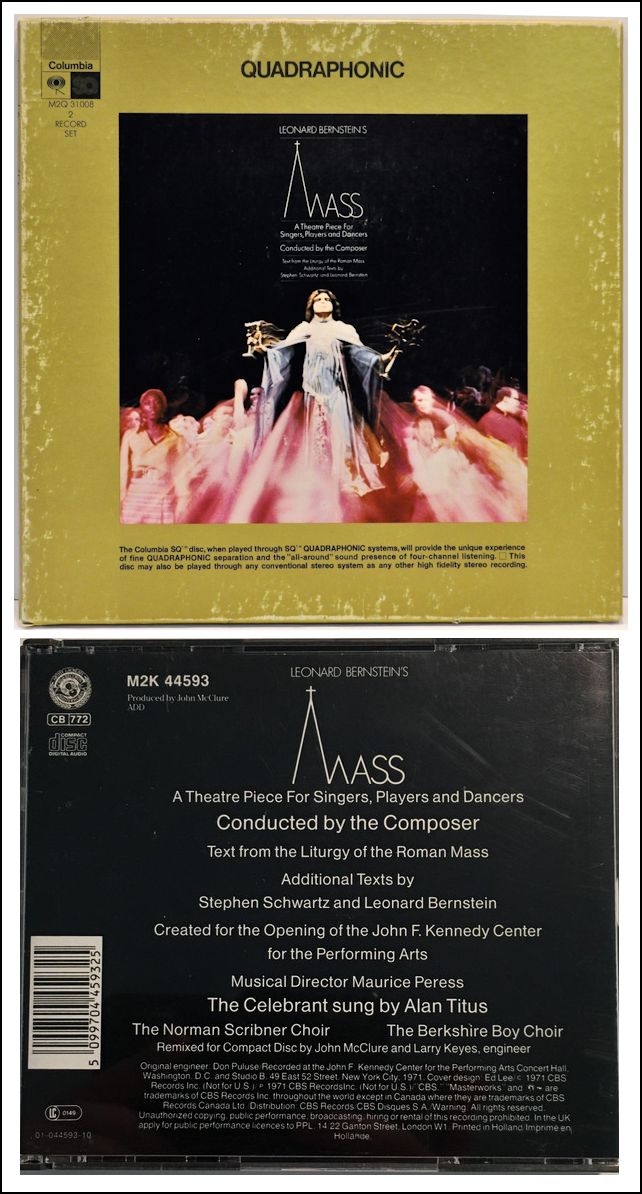

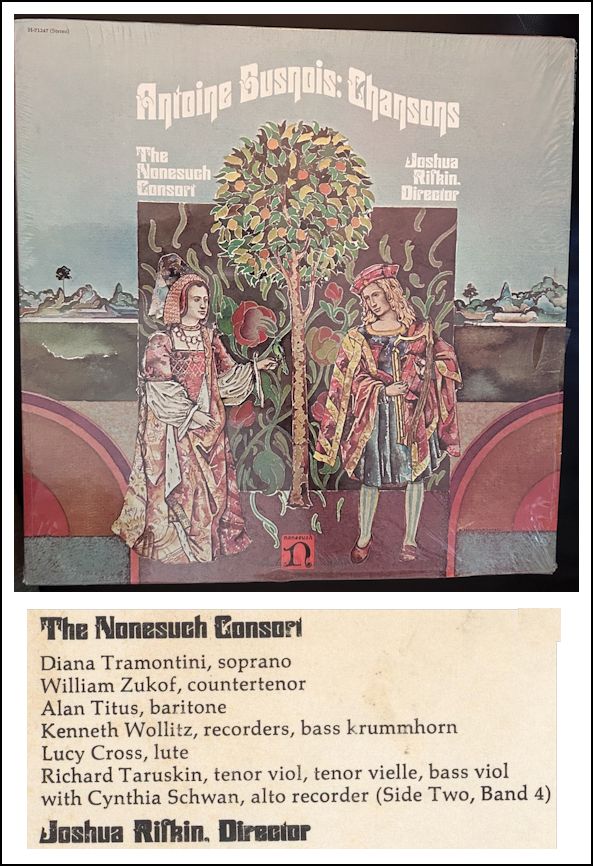

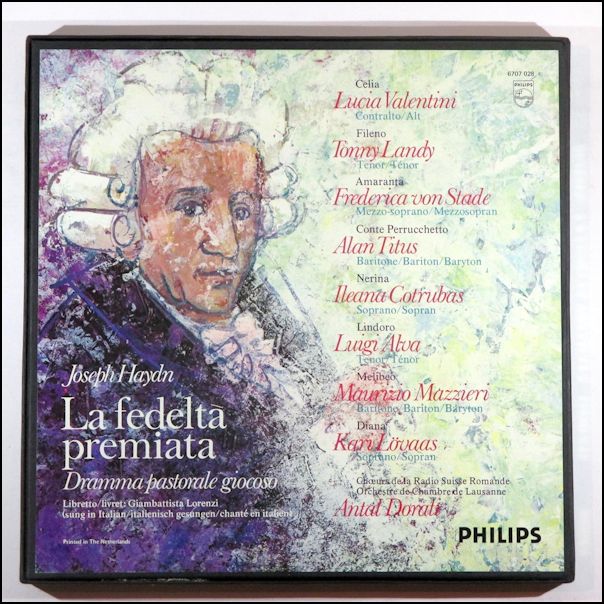

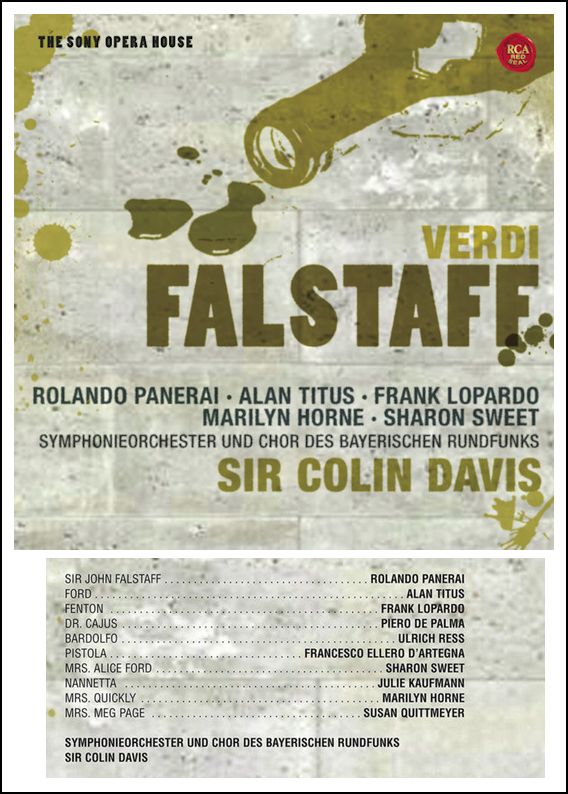

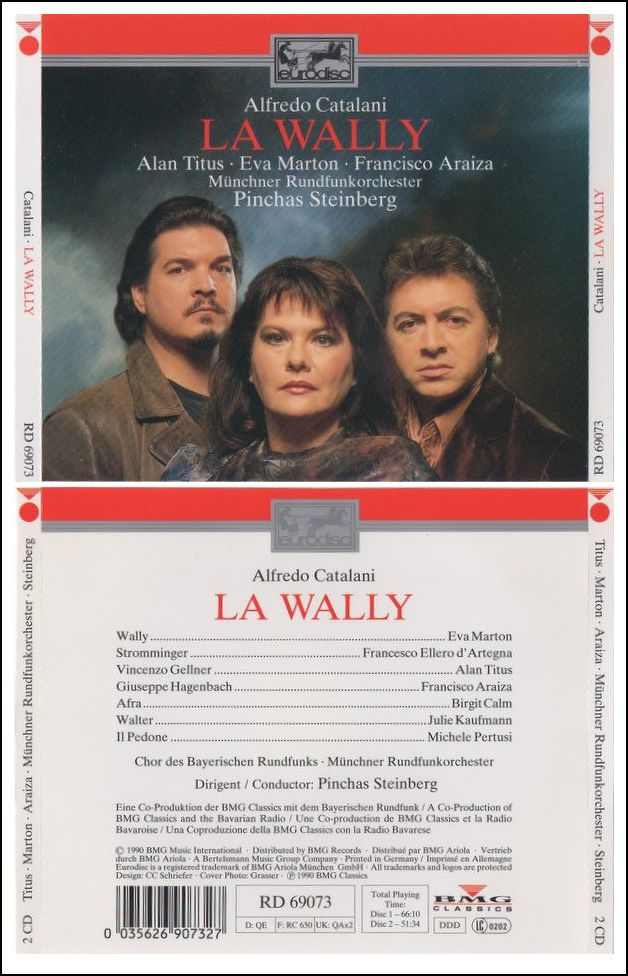

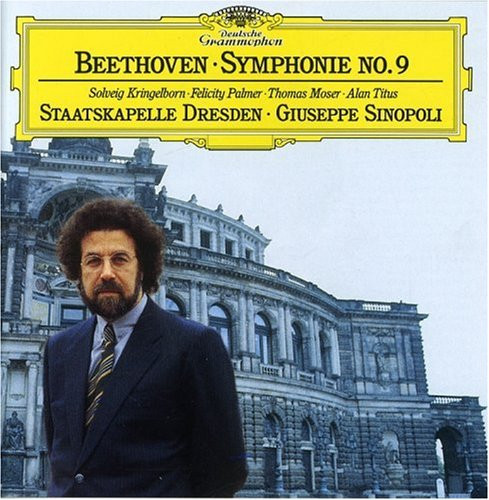

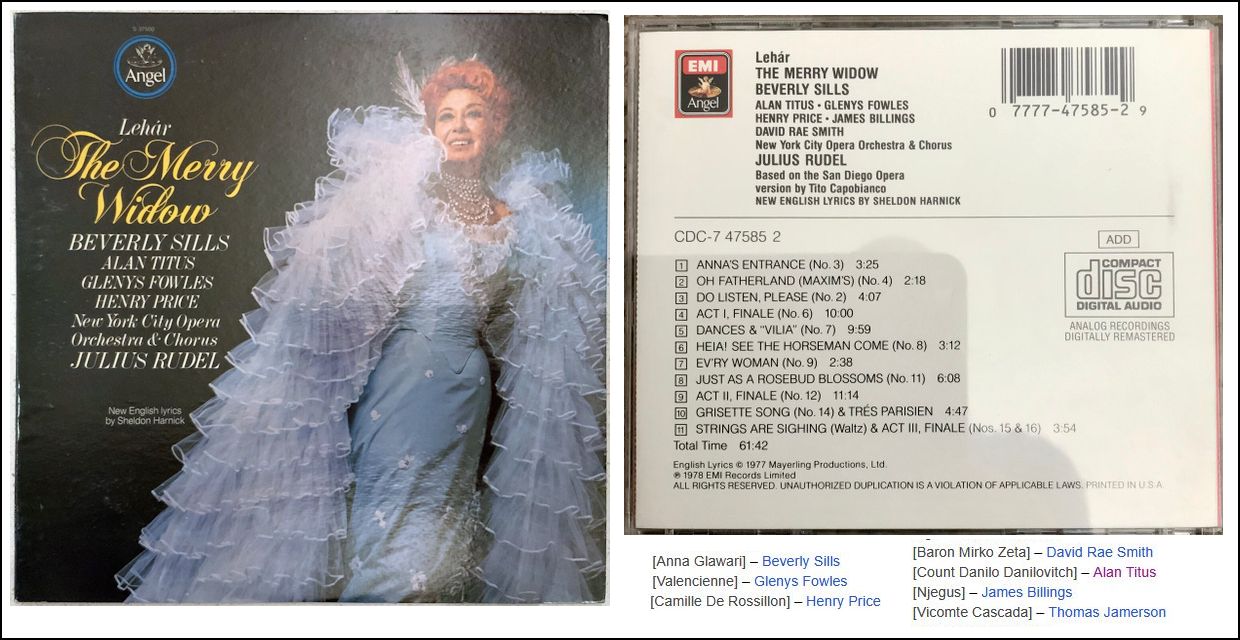

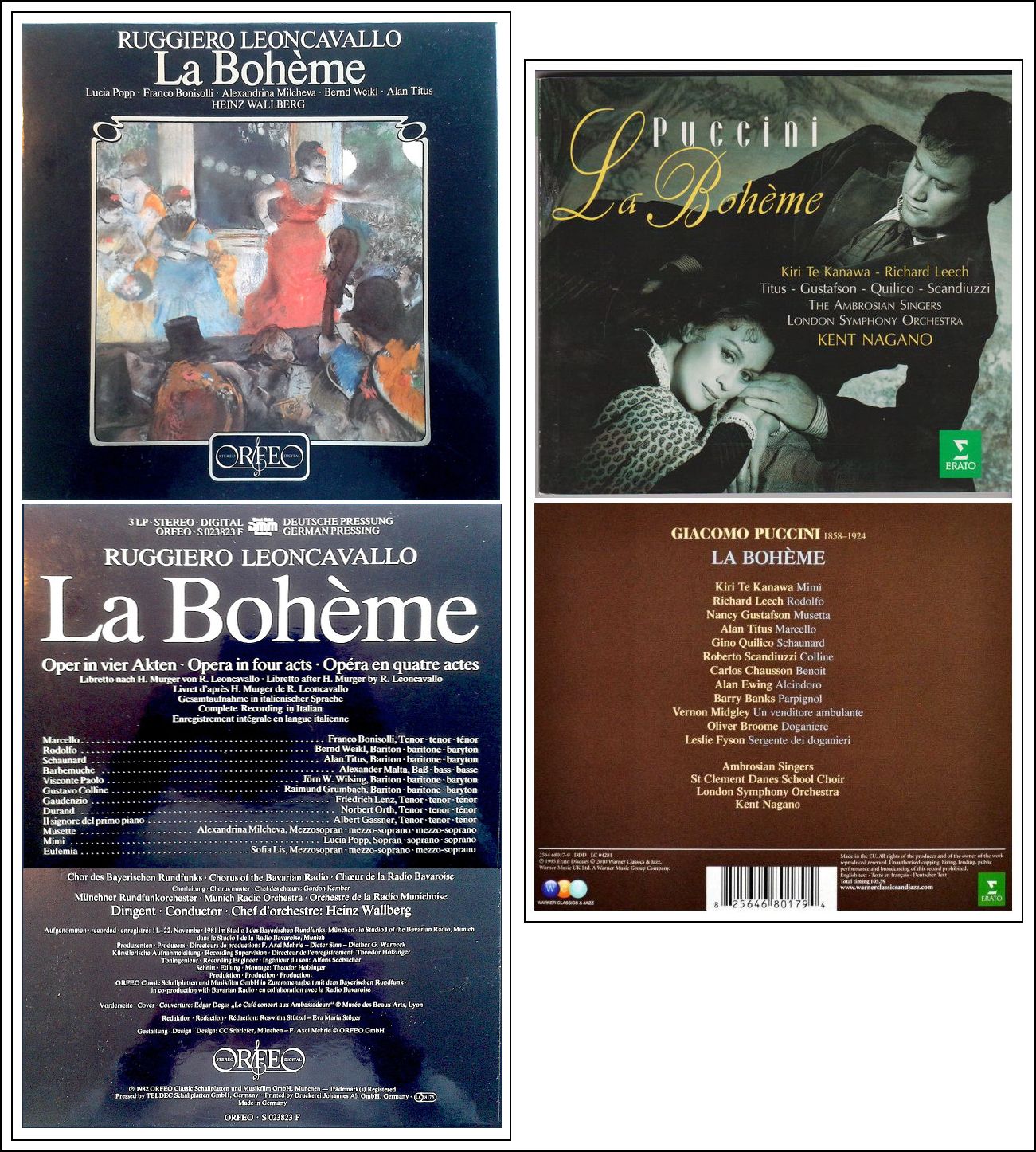

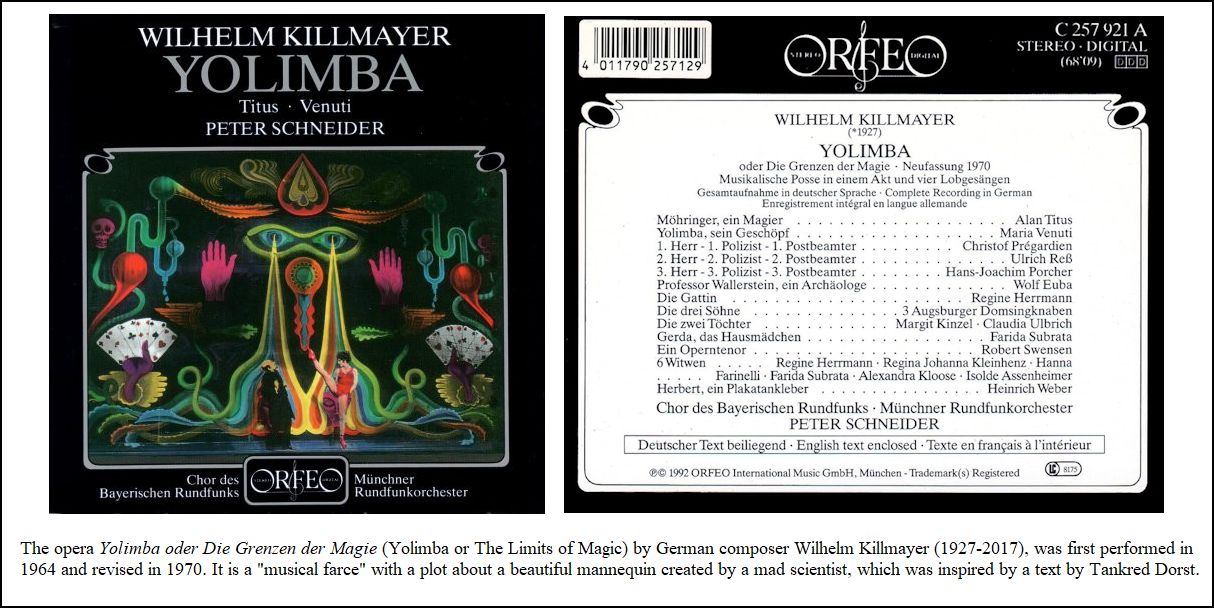

Alan Titus (born October 28, 1945) studied under Aksel Schiøtz at the Colorado School of Music, and Hans Heinz at The Juilliard School. His official debut was as Marcello in La bohème in Washington, D.C., in 1969. He came to prominence, however, in Leonard Bernstein's theatre piece MASS, creating the role of the Celebrant. MASS was commissioned by former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy for the September 1971 opening of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. Titus created the role of Archie Kramer in Lee Hoiby's Summer and Smoke (after Tennessee Williams) in St. Paul in 1971, and repeated the role in his New York City Opera debut that same year. He found a home at the New York City Opera, where he was a leading baritone for many seasons. He participated in nationally televised performances of Il barbiere di Siviglia (with Beverly Sills, 1976), Il turco in Italia (1978), La Cenerentola (opposite Susanne Marsee and Rockwell Blake, 1980), and Madama Butterfly (conducted by Christopher Keene, 1982). He made his only appearances with the Metropolitan Opera in 1976, as Harlekin in Ariadne auf Naxos, with Montserrat Caballé. In 1974, the baritone appeared in the world premiere of Hans Werner Henze's Rachel, la cubana, for WNET Opera Theatre, opposite Lee Venora and Marsee, conducted by the composer. In 1973, Titus made his European debut, in Amsterdam, as Pelléas in Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande. He has since been heard at Glyndebourne, Munich, Milan, Madrid, Barcelona, Vienna, Paris, Rome, London (Covent Garden), Berlin, etc. At the Teatro alla Scala, the baritone appeared in Arabella (1992), Elektra (directed by Luca Ronconi, 1994), La fanciulla del West (1995), Die Frau ohne Schatten (in Jean-Pierre Ponnelle's production, 1999), and Salome (2002). He made his Bayreuth Festival debut in 1998, in the title role in Der fliegende Holländer and repeated the role in 1999. At Bayreuth in 2000, he portrayed Wotan in Das Rheingold and Die Walküre and The Wanderer in Siegfried; and repeated all three roles in 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2004. He portrayed Wotan at the Teatro Real de Madrid in 2003. He returned to Bayreuth in 2009 to portray Hans Sachs in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. In 1994, the singing-actor was awarded the title of Kammersänger, in Munich. Titus retired in 2010, following a forty-year career.== Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Ubaldo Gardini (Poggio Renatico, 18 December 1924 – Ferrara, 24 November 2011 ) was an Italian singing teacher and musician who taught at the Royal Opera House in London, the Metropolitan Opera House in New York and the Tokyo University of the Arts . Born into a wealthy family, he inherited his interest in music from his father, Angelo, a self-taught accordionist. He began studying the violin as a child, and furthered his studies at the Frescobaldi Conservatory in Ferrara , where he continued studying viola, piano, composition, counterpoint, and harmony. At 17, he met Pietro Mascagni, who wanted him under his artistic tutelage. During the Second World War he obtained a diploma as a radio announcer and began to work in radio broadcasting, also writing for the magazine "Musica e registrazione".

From there he decided to remain in the United Kingdom, marrying the soprano in early 1954. In the meantime, he worked as a singing teacher with various theaters, including, in these years, La Scala for L'elisir d'amore . It took him almost a decade to establish himself as an Italian instructor in London, during which he gave private lessons to the numerous singers who requested them. It was only in 1963 that he established himself as a regular collaborator with Covent Garden as an Italian language coach. He took part in the 1967 Glyndebourne Festival and the following year collaborated with Sir Colin Davis on the recording of Mozart 's Idomeneo, published by Philips. Throughout his career, he has made a series of interventions on around fifty recordings, almost all of which were made for Philips and Decca, and 28 DVD editions of operas. Some academic articles are also known, including a Treatise on the Harmony of Music and an analysis of the different versions of Madama Butterfly. In addition to his vocal coaching, in the same years Gardini was also involved in the staging of some Mozart operas with Italian librettos, including The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così fan tutte . In 1981 he divorced Fisher and ended his tenure at Covent Garden. Around that time he had met the Hungarian Eva Kondra, a costume designer at Glyndebourne. Their relationship produced three children: Angelo, Susanna, and Michele. They remained living with her mother in Brighton when he decided to move to New York, where, in addition to working as an opera coach at the Metropolitan Opera, he signed a contract as second conductor and producer that kept him busy until 1984. He was subsequently appointed professor at the Juilliard School. In September of the same year, he was invited to Tokyo as a visiting professor of Italian Opera at the University of Arts and Music. There, he supervised Idomeneo, and the following year, Don Giovanni . There, he met the woman who would become his second wife, Reiko Sakuma, who preserved his memory after his passing. Although he no longer worked with internationally renowned singers in Tokyo, Gardini contributed to the promotion of Italian Opera, overcoming cultural differences and organizing courses with famous names such as Plácido Domingo and Frederica von Stade, broadening the horizons of his students, many of whom went on to successful careers. In 2004, at the age of eighty, Gardini resigned from his teaching position in Japan, but upon returning to Italy, he could not refuse the offer of teachers and singers to organize summer courses at his birthplace in Poggio Renatico. Having converted his home into an office, from 2005 onward he held courses until he was able to continue teaching. His last production was in 2007, when he organized and directed The Marriage of Figaro to celebrate the centenary of the University of Tokyo. The performance was given to a sold-out crowd at the Tokyo Bunka Kaikan, the city's most renowned opera house. Part of his library, consisting of more than 3000 volumes, including scores and books, often enriched by dense notations in his own hand, was donated to the library of the Vienna Conservatory. The copies annotated by the maestro were entrusted to Tokyo and made available to the students of the University of Music. His piano and another significant part of his collection of books, scores, opera librettos and records were donated to the Opera Academy of Verona. In May 2014, the Municipality of Poggio Renatico, in the presence of his widow and numerous personalities, awarded honorary citizenship to Ubaldo Gardini "for having particularly distinguished himself in his artistic field at an international level" . == This biography is slightly edited from the

Google translation of the article in the Italian Wikipedia

|

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 16, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1990, 1995, and 2000. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.